The

Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918

at the Norfolk Navy Ship Yard, Naval Training Station Hampton Roads

& the Norfolk Naval Hospital

Addendum: Lillian

M Murphy RN USNR (1887-1918) Navy Cross Recipient

John

G.M. Sharp

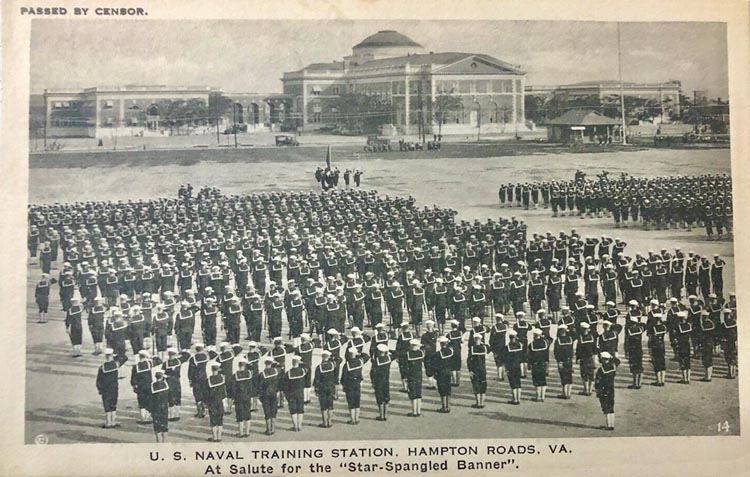

Introduction This paper examines the reasons for the outbreak and spread of the great 1918/1919 influenza pandemic on the Norfolk Navy Ship Yard, Naval Training Station Hampton Roads and Norfolk Naval Hospital and the efforts made to contain it. Outbreaks of diseases such as influenza on large scale in closely packed installations are devastating to employee health, productivity, and morale. One of the worst was the great influenza pandemic of 1918/1919. This pandemic struck the United States hard. Ultimately the death total for the nation was close to a million people. Because this virulent flu strain (H1N1) peaked initially among naval personnel on shore duty in the last weeks of 1918, one scholar has called this "largely a naval affair"1 The outbreak was often referred to as the "Spanish flu" but the 1918 pandemic did not, as many people believed, originate in Spain. This nickname was actually the result of a widespread misunderstanding to Spain’s consternation.2 Scientists are still unsure of its source. France, China, and Britain have all been suggested as the potential birthplace of the virus. In the United States the first known case was reported at a U.S. Army training facility located on Camp Funston in Kansas. On 4 March 1918 the first soldier at the camp reported ill with influenza at sick call. The camp held an average of 56,222 troops. Within three weeks more than eleven hundred others were sick enough to require hospitalization and thousands more – the precise number was not recorded – needed treatment at infirmaries scattered around the base.3 Modern scholars have increasingly focused their attention on the massive movement of large concentrations of military personnel in WWI as proximate cause for the swift spread of the virus. During WWI large numbers of military personnel were assembled in crowded army and naval shore stations or crossed the Atlantic to Europe and from the United States in packed troop ships which became perfect, though unwitting vectors, for disease transmission41 Crosby, Alfred W America’s Forgotten Pandemic the Influenza of 1918 (Cambridge University Press: New York 2004), 57

2 Kolata, Gina, Flu the Story of the Great Influenza Pandemic and the Search for a Virus Cure 2011

3 Andrews, Evan "Why Was It Called the 'Spanish Flu?' History 27 March 28, 2020

https://www.history.com/news/why-was-it-called-the-spanish-flu accessed 28 March 28, 20203a Barry, John M., “The Site of Origin of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic and its Public Health Implications.” Journal of Tanslational Medicine, 2, 20 January 2004. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC340389/ accessed 27 April 2020.

3b Barry, John M., The Great Influenza The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History (New York: Penguin Books, 2018), 92.

4 Crosby, p.57, 217

The Influenza Pandemic Arrives

The new influenza virus arrived in Virginia late in the summer of 1918, apparently brought by soldiers arriving to take ships from Norfolk and Newport News to the war in Europe. It quickly appeared among personnel at U.S. Navy and Army facilities training recruits for the war effort, and by September it began to spread throughout the state.5

5 Caelleigh, Addeane S. "The Influenza Pandemic in Virginia (1918–1919)." Encyclopedia Virginia, Virginia Humanities, 22 April 2019, Web. 7 April. 2020

By the end of September, thirteen men had died from influenza at the Norfolk Naval Base. After 350 new cases were reported in the city of Norfolk on October 2, Norfolk officials closed schools and public meeting-places.6 Norfolk schools, churches, and public gathering places were closed. Norfolk also opened an emergency hospital, and the city's doctors, druggists, and morticians worked day and night. The Times-Dispatch Richmond, Virginia, reported that the large number of furloughed soldiers from nearby military bases exacerbated the epidemic in the Norfolk area.7

6 Barker, Stephen Foster The Impact of the 1918-1919 Influenza Epidemic on Virginia (University of Richmond: UR Scholarship Repository2002), p. 13 https://scholarship.richmond.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2174&context=masters-theses

7 Barker, p. 23

The 1918/1919 influenza killed mostly young recruits in their late teens and early twenties. Why was this flu so deadly to this particular group? The answer, according to work by the University of Arizona evolutionary biologist Michael Worobey, had to do with the flu viruses those victims encountered as children, decades before. As dominant flu strains change over time, people born after 1889 had never encountered a strain similar to the Spanish flu, leaving them vulnerable in the pandemic.8 Flu symptoms included body temperatures up to 105 degrees, delirium, and as author Lynette Iezzoni puts it, coughing up of "pints of greenish sputum." Flu weakened the body’s defenses, often allowing secondary pneumonia, which caused most of the deaths, to invade, filling lungs with blood and other fluids and turning oxygen-deprived skin blue. Influenza occasionally led to other respiratory conditions or severe complications such as meningitis, internal bleeding, and organ damage.9 The great influenza pandemic devastated the Naval Training Station Hampton Roads where it arrived on 13 September 1918. During the pandemic 3005 recruits at the training station contacted the disease and 175 of them died.10 Most of the recruits were treated at Norfolk Naval Hospital and the naval hospital registers reflect the speedy spread of the virus. The first sailors admitted specifically for "influenza" date from 17 September 1918.11 The first three victims were Derrell Madison, Gustave Jensen and George Lloyd Ralph, all seaman second class in training at the Naval Training Station Hampton Roads. They were admitted suffering from influenza but fortunately recovered sufficiently to resume duty on 27 September 1918.12 Throughout the pandemic, accordance with wartime security, the Department of the Navy was reluctant to reveal the extent of the influenza outbreak, however leaks and rumors quickly disclosed the presence of virus at Norfolk to the nation.

8 The Atlantic 10 November 2016, Sarah Zhang, " Why Some Flus Are Deadliest in Young Adults : The first flu you get matters for the rest of your life." https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2016/11/flu-memory/507287/ accessed 16 April 2020

9 Army History No.111 Spring, 2019,p.29 Kathleen M. Fargey " The Deadliest Enemy U.S. Army and Influenza 1918 -1919" https://history.army.mil/armyhistory/AH-Magazine/2019AH_spring/AH111(W).pdf accessed 16 April 2020

10 Holbrook, Richmond A Century with Norfolk Naval Hospital p. 417

11 Department of the Navy, Case Files for Patients at Naval Hospitals and Registers Thereto: Registers of Patients 1812–1929, Series A4097. Textual records, NAI: 2745846 Record Group 52: Records of the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, 1812–1975, National Archives at Washington, D.C.

12 DON 1918 Norfolk Naval Hospital Case files p. 128 patients 3337-3339e

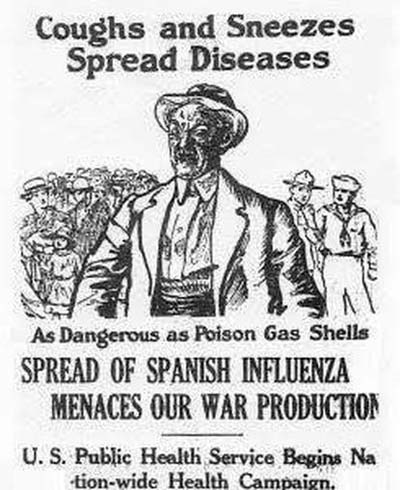

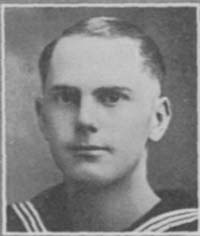

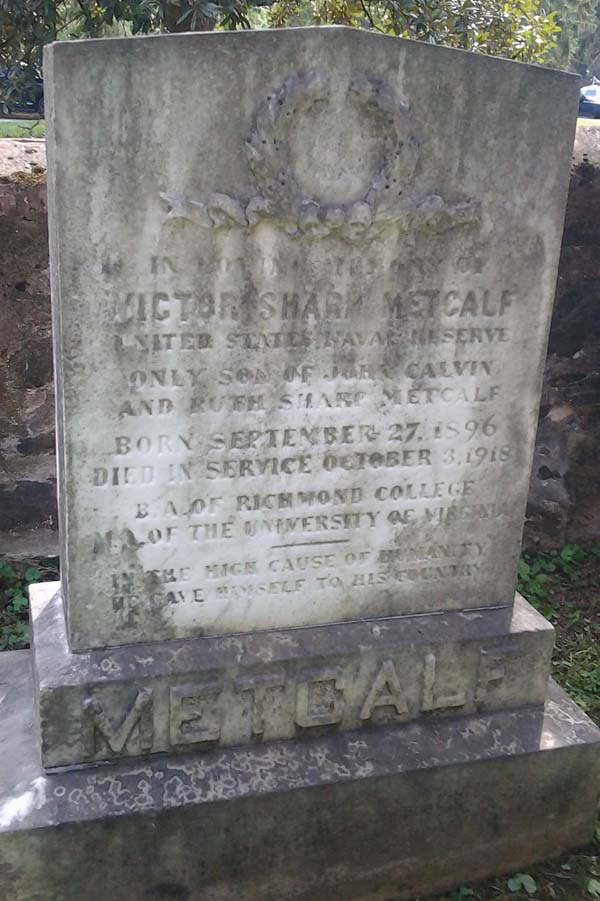

Public Health Poster 1918Despite official reluctance, word of the outbreak was widely and rapidly disseminated. For example on 3 October 1918 the Richmond Times Dispatch included an article regarding the tragic death of Edwin Stewart Granger, Yeoman 1st Class USNR at Norfolk Naval Hospital. The young yeoman was a salesman in civilian life had only enlisted in the navy six months previously. Granger had married Margaret Williams of Highland Park just a month previously. At his death Edwin Granger was twenty-nine years of age; his body was returned to his family in Richmond for burial.13 On 4 October 1918 the Richmond Times Dispatch list of the dead from influenza included seaman 2nd class Victor Sharp Metcalf, the only child of the former dean of Richmond College and professor of English literature at the University of Virginia J.C. Metcalf. Seaman Metcalf a graduate of Richmond College, was twenty-two years old when he died early in the morning on 3 October at Norfolk Naval Hospital. The young sailor’s "parents were at his side when he died from pneumonia following an attack of influenza."14 On 10 October 1918 the Evening Star of Washington DC ran an article and photo regarding the death of Harold Flournoy Brooks, Yeoman 2nd Class USNR. Brooks was the son of prominent local family and had died at Norfolk Naval Hospital on 6 October 1918.

13 Richmond Times Dispatch 3 October 1918, p. 7

14 Richmond Times Dispatch 4 October 1918, p.7

On 11 October 1918 the Richmond Times Dispatch carried a story "Sailor Flu Victims Not Down-hearted". Frank C. Fisher finds his boy and others smiling at the ravages of the malady" The editor included some details of Fisher’s trip to visit his ailing son Seaman second class John Fisher at the Norfolk Naval Hospital. Fischer senior reported he found his son John and "all the boys… game fellows fighting the flu and pneumonia like good soldiers."15 By December the disease rate was slowing down, however just before Christmas on 23 December 1918 Captain Robert Combs Greenwell USN died at the Norfolk Naval Hospital. Captain Greenwell was a native of the District of Columbia. He was born on 4 July 1884 and had served in the United States Coast Guard on Revenue Cutters and later transferred to the U.S. Navy where he served on the USS Florida and USS Mayflower. Captain Greenwell left behind a grieving widow and family. He is buried in the Congressional Cemetery Washington DC.16

15 Richmond Times Dispatch 11 October 1918, p.7

16 Evening Star Washington DC 23 December 1918, 7

Norfolk influenza outbreak is national news

On 22 October 1918 the Rogue River Courier, of Rogue River Oregon carried the details of letter from Miss Bernice Umphlette then residing in Norfolk to her sister with the banner headline "Terrible Death Toll Norfolk". Umphlette wrote"

"We are having a terrible siege of Spanish Influenza. Really, people are dying by the hundred. They are using school buildings for hospitals and all public places such as barber shops, schools, churches shows etc. are closed. The disease is very contiguous but I have not caught it thus far. There are so many dying that the undertaker can scarcely take care of the bodies. The condition is awful; it is like war…" 17

17 Rogue River Courier Rogue River Oregon 24 October 1918, p. 1

Almost 9,000 cases of influenza were documented in Norfolk and by October 8, 1918, at least 3,500 of these were on the naval station.

At the end of the year almost 1,000 deaths were reported by health officials in the area, but it is suspected the number was far more substantial as many did not seek out medical care.Two Naval Nurses in Wartime

During the pandemic "the terrible truth was there was no effective medical intervention; doctors were virtually helpless. But nurses were not. The best that could be done for the afflicted was to provide them with soups, baths, blankets, and fresh air until the disease or the patient died. This enormous task fell on the large group of naval nurses and medics."18 By the time of the armistice on 11 November 1918, over 1550 nurses had served in naval hospitals and other facilities at home and abroad. During the war, 19 Navy nurses died on active duty, over half of them from influenza. Three of the four Navy Crosses awarded to wartime Navy nurses were given posthumously to women who sacrificed their lives during the 1918 flu pandemic.

18 Wallace, Mike Greater Gotham A History of New York City from 1898 to 1919 Oxford University Press: New York 2017), p. 1010

Two navy nurses died while comforting ailing and dying sailors. One of these was navy nurse Hortense Elizabeth Wind (1891 -1918) USN. Nurse Wind was the chief dietitian at the Norfolk Hospital. She was from Council Bluffs, Iowa, and a graduate Iowa State University. In late summer of 1918 she was assigned to the hospital where she often worked long hours during the epidemic. Nurse Wind came down with influenza in early December, which quickly turned into pneumonia. She died on 10 December 1918. Her body was returned to her home town where she was given hero’s funeral complete with military band from Fort Dodge. As the band played Nearer My God to Thee, her flag draped coffin was lowered in the grave and a firing squad fired the farewell salute.19 The second nurse who lost her life in the line of duty and played a vital role during the pandemic was Ann Marie Dahlby. Nurse Dahlby was born in Minneapolis, Minnesota, on 23 October 1892 and grew up in a large family of prosperous Danish immigrants. Working closely with patients she came down with influenza on 18 November and died at the naval hospital of pneumonia on 26 November 1918. She was twenty six years of age at the time of her death; her name is listed among those nurses who died in service to their country.20

19 Omaha World–Herald 18 December 1918, p.1

20 The Trained Nurse and Hospital Review, Volumes 62-63 January to December 1919 (Lakeside Publishing: New York City 1919), 119

https://books.google.com/books?id=lYhMAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA119&lpg=PA119&dq=Ann+Marie+Dahlby+RN&source=bl&ots=e0XfRHYEvW&sig=

ACfU3U1VK07p4NZYI1w92gR8FnOPPLYhmQ&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj16JHe5O3oAhVGbKwKHWrPClcQ6AEwAHoECAcQLA#v=onepage&q=

Ann%20Marie%20Dahlby%20RN&f=false accessed 16 April 2020So quickly did the epidemic erupt from the first reported cases at the navy base in Norfolk and docks in Newport News that the deadly virus seemed less like a disease and "more like some diabolical wildfire"21 As the number of new influenza cases and deaths decreased, Norfolk health authorities lifted their ban on November 1, 1918, however physicians had to examine children for signs of influenza before they were allowed to return to school.22

21 Mark and Merickson Coffins and Quarantine Staggered Hampton Roads during its Deadly Bout with the Spanish Flu

http://www.dailypress.com/features/history/our-story/dp-hampton-roads-staggered-from-its-deadly-bout-with-the-spanish-flu-in-1918-20131030-post.html

accessed 26 April 202022 Barker, p.36

During the height of the epidemic and as morbidity soared, the city of Norfolk soda shops substituted paper cups for the usual glass variety. Norfolk officials required soft drinks to be served in paper cups and ordered restaurants to sterilize all cooking utensils and silverware.23

23 Barker, pp. 106-107

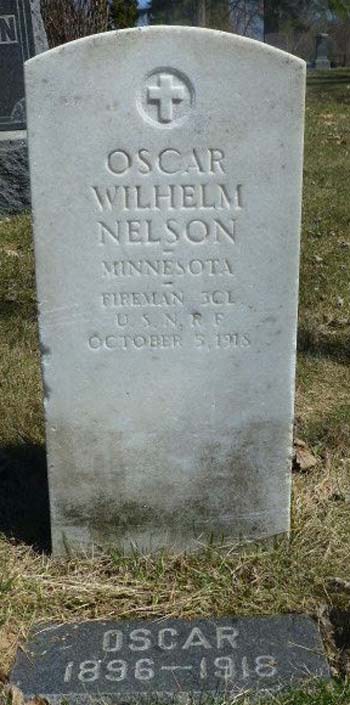

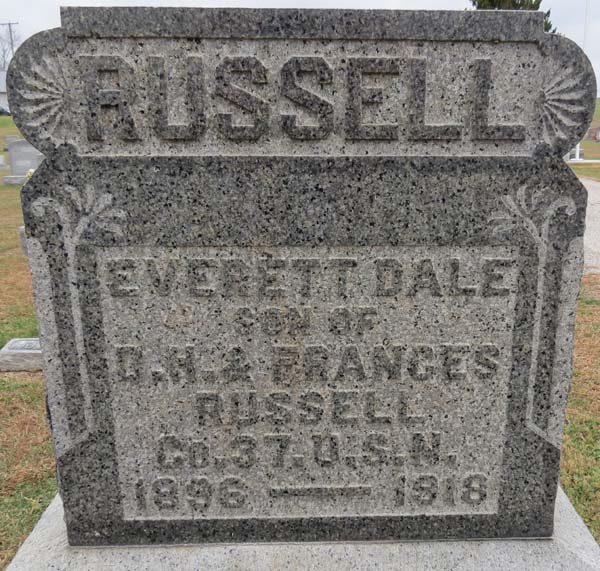

The Great Pandemic and Collective Memory

Writing after the war Captain Richmond C. Holcomb USN noted, "It was over quickly, took its toll of dead and was over, so far as the epidemic intensity was concerned in about four weeks."24 As the mortality rate steadily declined, the men and women of the Norfolk Naval Shipyard, Naval Training Station Hampton Roads and Norfolk Naval Hospital returned to their shops and offices. By the time the pandemic finally ended in late 1919, it had killed around 25 times more people than any other flu outbreak in history. All over America families received word of the sudden and unexpected death of beloved sons and daughters. It killed both rich and poor all over the globe; possibly it killed more people than the first and second world wars put together. In the United States wartime secrecy regulations regarding this trauma and the vast number of deaths abetted this process.25 After the war, given the utter helplessness to control influenza, leaders and the public began to downplay the epidemic as a significant event. Unlike recent tragedies, there were no national memorials erected, public ceremonies or moments of silence for the hundreds of thousands of victims; in effect erasing this dramatic story from history and our collective memory.26 Today except for individual family grave markers there are but few reminders of the victims of our great pandemic.

24 Holcomb, 438

25 Kettle, Martin, The Guardian, 25 May 2018, A Century on, Why are we Forgetting the deaths of 100 million?

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/may/25/spanish-flu-pandemic-1918-forgetting-100-million-deaths Accessed 28 March 28, 202026 Byerly, Carol R. Fever of War The Influenza Epidemic in the U.S. Army during World War I (NYU Press: New York 2005)

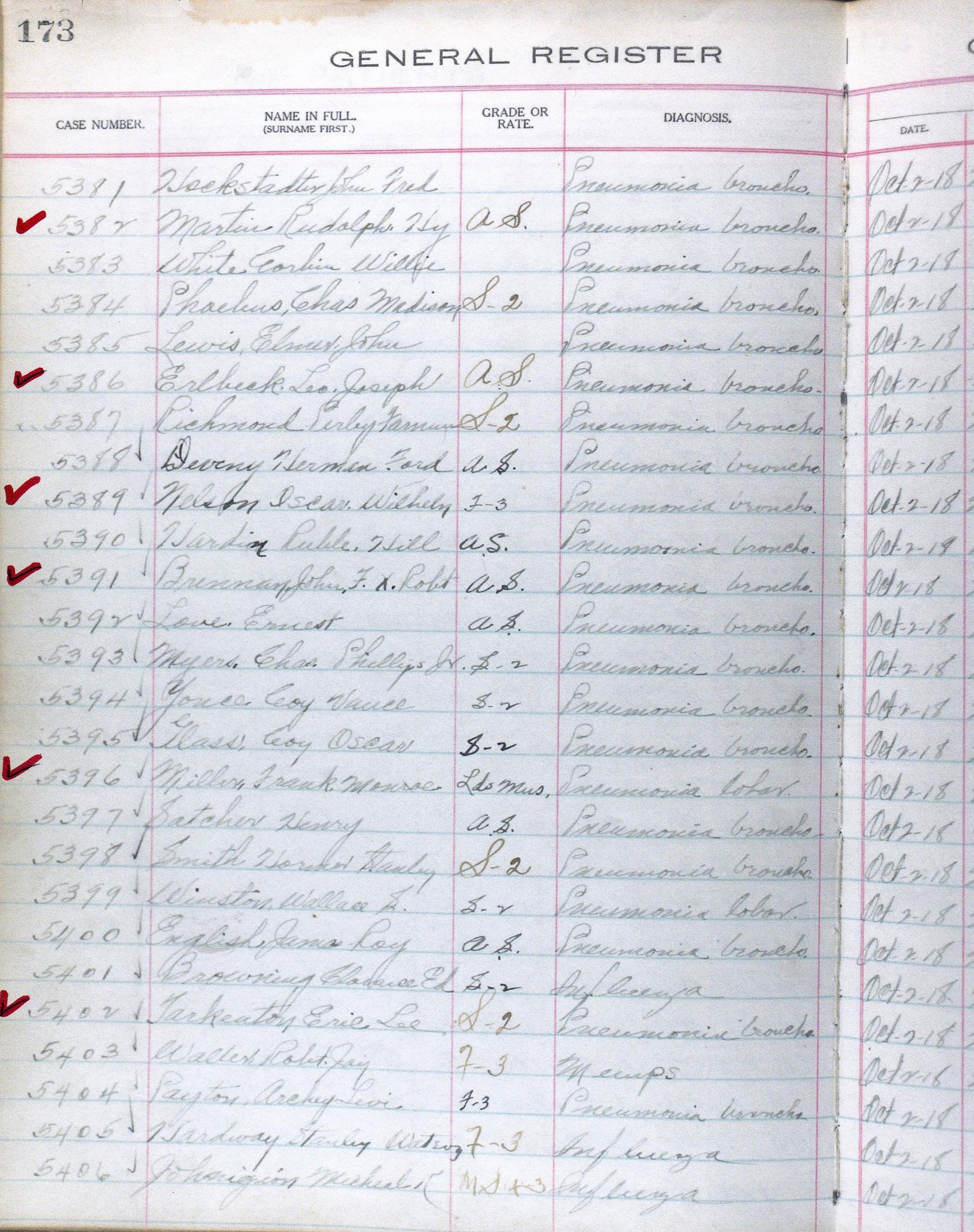

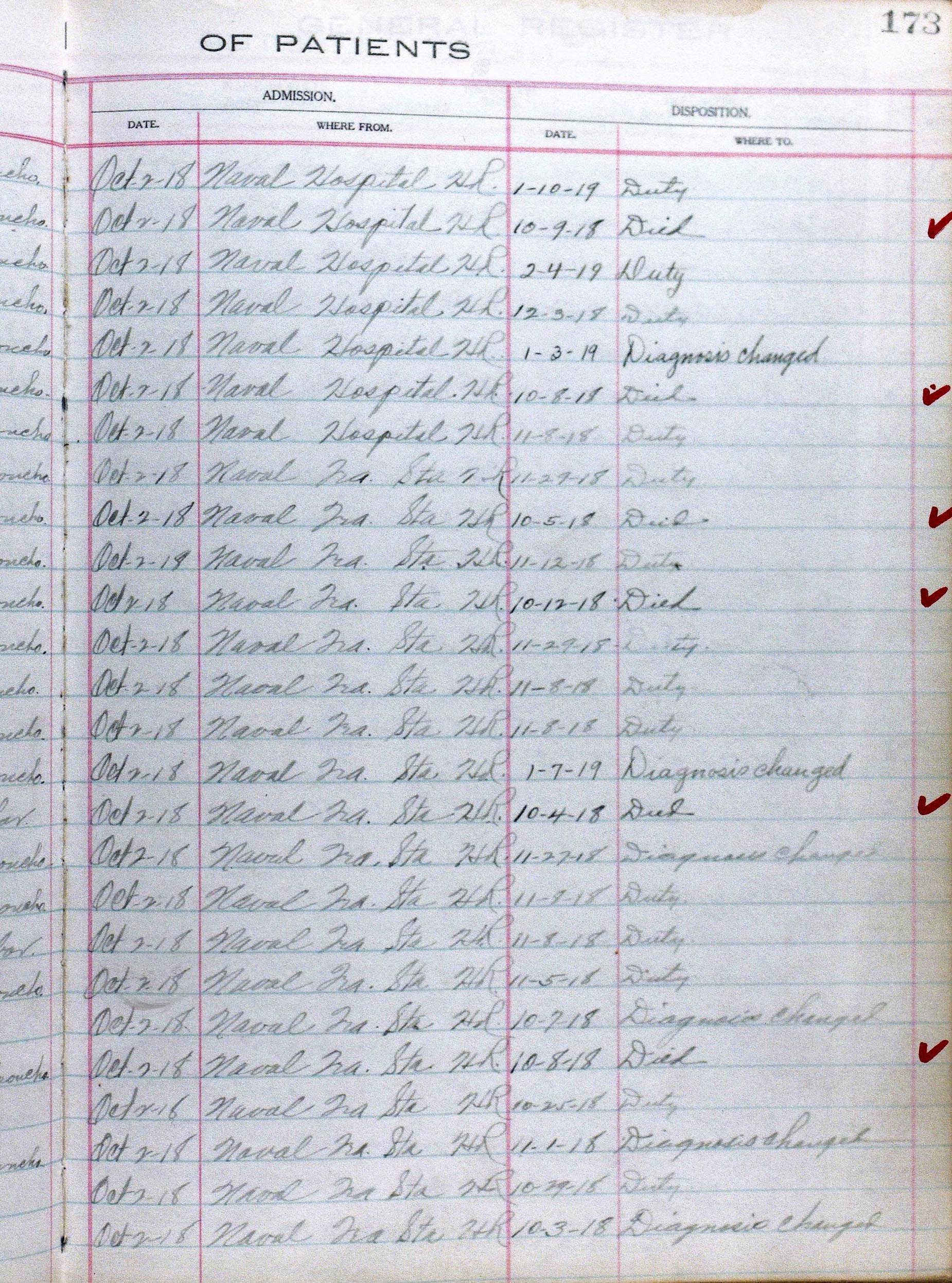

October 2, 1918, Norfolk Naval Hospital Register

5 marked deaths

(Enlarge in browser)

The following is a summary of the data on six naval recruits from the Naval Training Station Hampton Roads admitted to Norfolk Naval Hospital on 2 October 1918. The recruits below are enumerated on the General Register of Patients page 173. The cause of death for each recruit is listed as pneumonia. At Norfolk hospital after a patient progressed from influenza to pneumonia, death typically followed within an average of six days in the small sample below. The 1918 pandemic struck hardest at the young, the average age of death for the six recruits below was age 20, most were away from home for the first time and had only been in the navy three or four months. The recruits names and related data were summarized from the Norfolk Naval Hospital General Register page 173, see the above images of the original where the cases cited are checked in bold. The recruits birthdates and cause of death were confirmed in the State of Virginia Death Records. The young sailors listed below are but a small sample of 175 who died from the training station during the great influenza pandemic of 1918/1919. During the outbreak pneumonia was the most frequent complication cited by Naval Hospital Norfolk where 30% of all cases admitted subsequently developed pneumonia. The fatality rate for this disease overall during the pandemic was an astounding 28.6%.” 27, 28, 29

Name Rank Enlistment Admission Death Born Martin, Rudolph Henry Apprentice Seaman 20 July 1918, Columbia, SC 2 October 1918 9 Oct0ber 1918, age 18 1 January 1899, Erlbeck, Leo Joseph Apprentice Seaman 19 July 1918, Baltimore, Md 2 October 1918 10 October 1918, age 21 7 January 1897, Nelson, Oscar Wilhelm Fireman 3/c 3 June 1918 Cincinnati, Oh 2 October 1918 7 October 1918, age 21 11 November 1896 Brennan, John Francis

Xavier RobertApprentice Seaman 29 July 1918, Washington, DC 2 October 1918 7 October 1918, age 21 22 November 1896 Miller, Frank Monroe Landsman Musician 5 August 1918, Baltimore, Md 2 October 1918 9 October 1918, age 18 12 January 1900 Tarkenton, Eric Lee Seaman-2/c 14 June 1918, Norfolk, Va 2 October 1918 6 October 1918, age 21 23 November 27 Department of the Navy, Case Files for Patients at Naval Hospitals and Registers Thereto: Registers of Patients 1812–1929, Series A4097. Textual records, NAI: 2745846 Record Group 52: Records of the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, 1812–1975, National Archives at Washington, D.C. General Register of Patients Norfolk 2 October 1918, page 173 sides A and B..

28 Holbrook, Richmond A Century with Norfolk Naval Hospital (Printcraft Publishing Portsmouth Virginia 1930), 417

29 Virginia, Deaths, 1912–2014, Virginia Department of Health, Richmond, Virginia

* * * * * * * * * *

John G. "Jack" Sharp resides in Concord, California. He worked for the United States Navy for thirty years as a civilian personnel officer. Among his many assignments were positions in Berlin, Germany, where in 1989 he was in East Berlin, the day the infamous wall was opened. He later served as Human Resources Officer, South West Asia (Bahrain). He returned to the United States in 2001 and was on duty at the Naval District of Washington on 9/11. He has a lifelong interest in history and has written extensively on the Washington, Norfolk, and Pensacola Navy Yards, labor history and the history of African Americans. His previous books include African Americans in Slavery and Freedom on the Washington Navy Yard 1799 -1865, Morgan Hannah Press 2011. History of the Washington Navy Yard Civilian Workforce 1799-1962, 2004.

https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/browse-by-topic/heritage/washington-navy-yard/pdfs/WNY_History.pdf

and the first complete transcription of the Diary of Michael Shiner Relating to the History of the Washington Navy Yard 1813-1869, 2007/2015 online:

https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/d/diary-of-michael-shiner.html

His most recent work includes Register of Patients at Naval Hospital Washington DC 1814 With The Names of American Wounded From The Battle of Bladensburg 2018,

https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/r/register-patients-naval-hospital-washington-dc-1814.html

The last three works were all published by the Naval History and Heritage Command. John served on active duty in the United States Navy, including Viet Nam service. He received his BA and MA in History from San Francisco State University. He can be reached at sharpjg@yahoo.com

* * * * * * * * * *

Norfolk Navy Yard Table of Contents

Birth of the Gosport Yard & into the 19th Century

Battle of the Hampton Roads Ironclads