Confederate

Slave Payrolls 1861 – 1865

Federal Records that Help Identify Former Slaves and Slaveholders

by

John G.M. Sharp

|

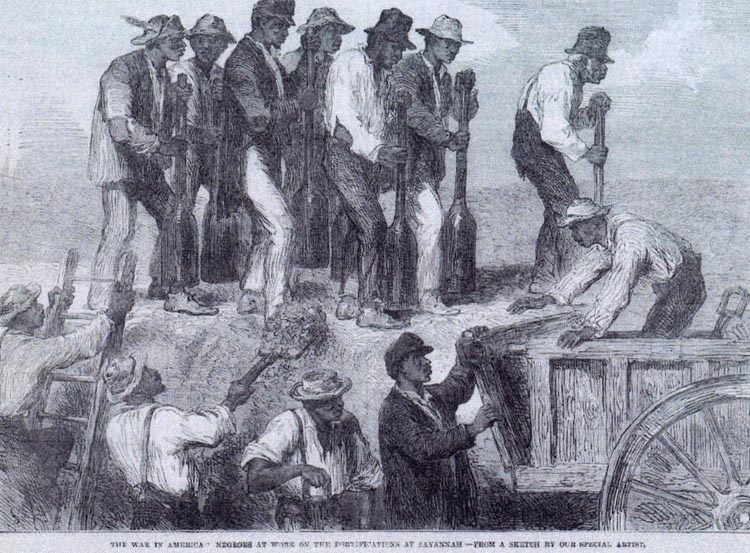

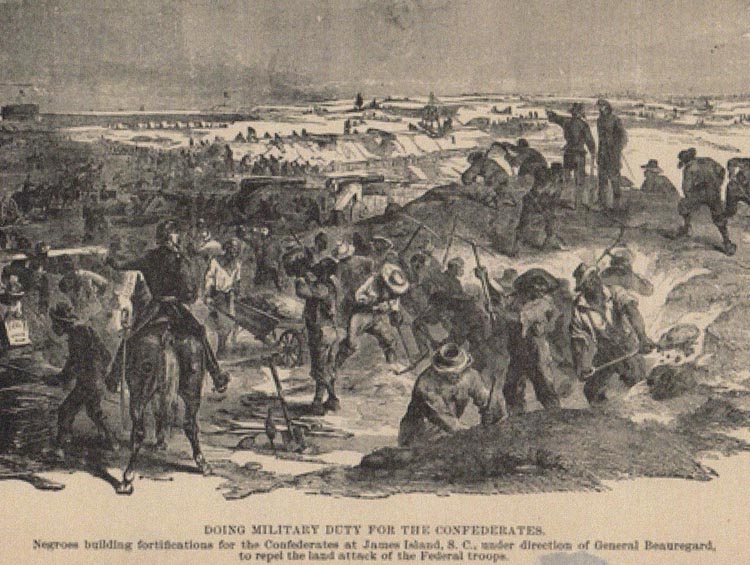

Enslaved laborers loading niter at Savannah Georgia and building Confederate fortifications at James Island S.C

For researchers and genealogists these newly released Confederate documents (RG NARA 109) are a treasure trove. These payrolls and receipts detail Confederate government expenditures and enumerate the names of many anonymous slaves — most by first names though some include surnames. For all of March 1862, a man named Ben cooked for the Confederate military stationed at Pinners Point, VA, earning 60 cents a day that would go to slaveholder John Jones.1 All payrolls provide some record of the slaveholders themselves as they are signed by the owners themselves or their representatives, acknowledging, like John Jones, that they had been paid for the use of the people they enslaved. Although the sums listed beside each name on the payroll would go to their owner and not the slave who performed the labor, the documents provide a rare record of enslaved persons. These documents were all scanned over the course of the last seven years by the staff of the National Archives and are searchable by town or region.

1 Macchi, Victoria, Confederate Slave Payrolls Shed Light on Lives of 19th-Century African American Families 4 March 2020, National Archives News, National Archives and Records Administration https://www.archives.gov/news/articles/confederate-slave-payrolls-digitized accessed 25 July 2020

Thousands of these Confederate States of America slave payroll documents were seized by Union forces after the Civil War have recently been digitized and are now on line at the National Archives and Records Administration. https://catalog.archives.gov/search?q=slave%20payrolls%20norfolk&f.ancestorNaIds=438

These documents reflect the fact the Confederate government amid the other crimes of slavery hired or forced thousands of enslaved people to labor in brutal conditions for the war effort, while slaveholders reaped the income.22 Ruane, Michael E. During the Civil War, the enslaved were given an especially odious job. The pay went to their owners. Washington Post 9 July 2020

Slavery was from the start central to the Confederate States and enslaved labor figured prominently on the CSA Corps of Engineers payrolls. On March 21, 1861, the vice president of the new Confederate government Alexander H. Stephens gave his famous "Cornerstone Speech" in Savannah, Georgia. In it Stephens declared that slavery was the natural condition of blacks and the foundation of the new Confederacy. He declared that, relative to the U.S. Constitution, "Our new Government is founded upon exactly the opposite ideas; its foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery, subordination to the superior race, is his natural and normal condition.3 "The Confederacy's early military successes depended significantly on slavery. Slaves provided agricultural and industrial labor, constructed fortifications, repaired railroads, and freed up white men to serve as soldiers. Tens of thousands of slaves were used to build and repair fortifications and railroads, as haulers, teamsters, ditch diggers, and assisting medical workers. In their role, slaves in the army were heavily relied on and in some cases overworked to the point of illness or death. During the Civil War enslaved and free blacks provided even more labor than usual for Virginia farms when 89 percent of eligible white men served in Confederate armies.4

3 Dew, Charles B. Apostles of Disunion Southern Secession and the Causes of the Civil War (University Pres of Virginia: Charlottesville 2001), 14

4 "How Did Slaves Support the Confederacy?" Virginia Museum of Art and Culture accessed 24 July 2020

https://www.virginiahistory.org/collections-and-resources/virginia-history-explorer/american-turning-point-civil-war-virginia-1/howAt the beginning of the Civil War both the Union and Confederate governments saw the control of Norfolk Navy Yard as crucial to victory. President Lincoln's Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles emphasized the importance of Norfolk's Navy Yard and the surrounding harbor to the government. Welles encouraged action to insure their occupation by Union forces. Thus the Union government planned to insure supremacy by maintaining control of Fort Monroe and surrounding installations.5 In response the Confederate government reinforced defense works at various locations. Virginia Governor John Letcher sent Colonel Andrew Talcott CSA, the state’s chief engineer, to Norfolk to superintend and hasten the construction of defensive batteries. Talcott also supervised the deployment of the enslaved laborers at the Naval Hospital (131 slaves), Fort Norfolk (197 slaves), Craney Island (82 slaves), Tanner’s Creek (27 slaves), Sewell's Point (115 slaves), Pig Point (72 slaves), St. Helena (42 slaves), Fort Boykins (118 slaves), Lamberts Point (30 slaves), and areas along the Elizabeth River and Norfolk Harbors (60 slaves). In addition, 874 slave laborers from Norfolk and 650 free blacks from the surrounding counties and Petersburg were utilized to sink small craft or anchor rafts across rivers. Most of the batteries were abandoned, however, when the Confederates evacuated Norfolk on May 10, 1862.

5 Newby-Alexander, Cassandra, "The world was all before them": A study of the black community in Norfolk, Virginia, 1861-1884" (1992), 18-19. Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623823. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-m5z1-dr2 accessed 24 July 2020

The following payrolls are examples of the scope of work at Craney Island, payroll number 7, at Sewell's Point, payroll number 240 and at Pinners Point, payroll number 1032. The work began on May 18, 1861; Confederate troops began erecting land batteries at Sewell's Point (pay roll 240) opposite Fortress Monroe utilizing hundreds of enslaved blacks in work brigades.6

6 Newby-Alexander, Cassandra, Ibid., 17

During the course of the war whenever enslaved people found an opportunity, they escaped to federal lines. This desire for freedom amid the successes of the Union army in Georgia can be clearly seen in an August 1864 payroll number 3831 for the Macon Arsenal AKA "Macon laboratory". During the American Civil War, Macon served as the official arsenal of the Confederacy. This CSA payroll enumerates 102 enslaved people working at the Macon laboratory. Of these 65 enslaved individuals at great risk managed to flee to freedom.7

7 Spraggins, Tinsley Lee. MOBILIZATION OF NEGRO LABOR FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF VIRGINIA AND NORTH CAROLINA, 1861-1865. The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. 24, no. 2, 1947,175 -180 . JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/23514947. Accessed 24 July 2020.

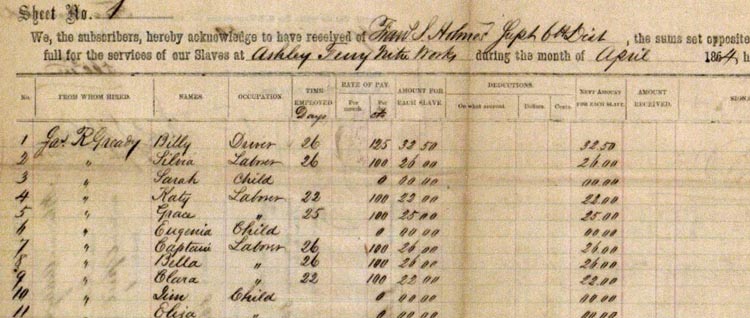

Detail slave payroll, April 1864 (Slave Payroll 4994) Ashley Ferry, Niter Works, South Carolina.Over 90% of the enslaved laborers enumerated on Confederate slave payrolls are men. However, women, and even children such as Sarah, Eugenia, Jim and Olivia, worked at Ashely Ferry Niter Works. This was odious work. The niter beds were large rectangles of rotted manure and straw, moistened weekly with urine, dung water, and liquid from privies, cesspools and drains, and turned over regularly, according to accounts at the time. The process was designed to yield saltpeter, an ingredient of gunpowder, which the Confederate army desperately needed during the Civil War. The wages for this repulsive task went, of course, not to those toiling in the beds, but to their owners.8 Example of the documents mentioned follow, to search the entire collection of Confederate slave payrolls in the National Archives online catalog at https://catalog.archives.gov/search?q=719477These payrolls include slaves from Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina, Virginia. A few payrolls include white employees (payroll 3482, 3481, 386, 5473, 148), free African Americans (payroll 386, 387), or notations that a particular slave or slaves, escaped (3831).9

8 Ruane, Ibid.

9 Kluskens, Claire Federal Records that Help Identify Former Slaves and Slave Owners National Archives and Records Administration accessed 26 July 2020 https://www.archives.gov/files/calendar/genealogy-fair/2018/2-kluskens-handout.pdf

John G.M. Sharp

25 July 2020* * * * * * * * * *

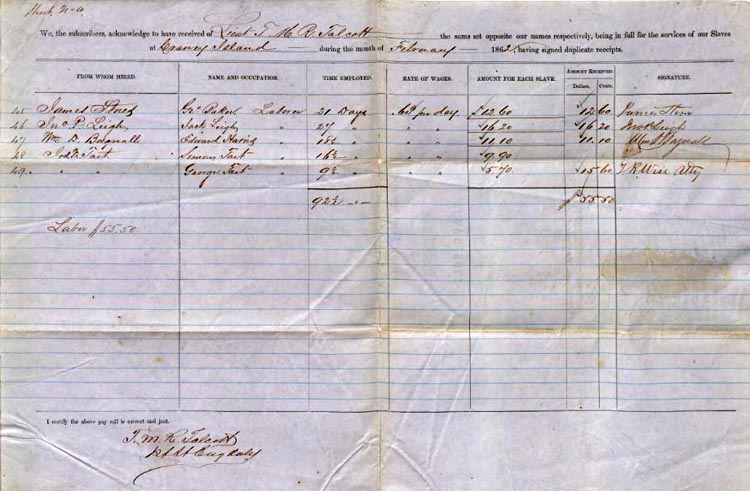

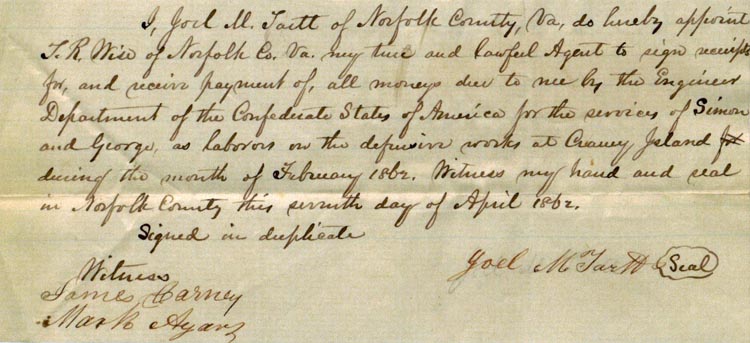

Slave Payroll number 7 (above), 7 February 1862 Craney Island Virginia

This payroll listed enslaved workers employed at Craney Island. Five men are enumerated with their name and surname. Craney Island proved to be of strategic significance during the Civil War for the defense of Norfolk as it is near the entrance to the Elizabeth River. This payroll acknowledges that Lieutenant T. M. R. Talcott paid certain Norfolk County, Virginia, slave owners for work performed by their slaves at Craney Island, Virginia, relating to the defenses of Norfolk, Virginia, during February 1862.

Slaveholder James Stones provided a slave named George Baker, Slaveholder John P. Leigh provided a slave named Jack Leigh, Slaveholder William D. Bagnall provided a slave named Edward, Slaveholder Joel M. Tart, provided two enslaved men named Simon Tart and George Tart. T.R. Wise acknowledged receipt of payment for Joel M. Tart, whose power of attorney was witnessed by James Carney and Mark Ayar [or Ayars]. The other slaveholders acknowledged receipt of payment for themselves.

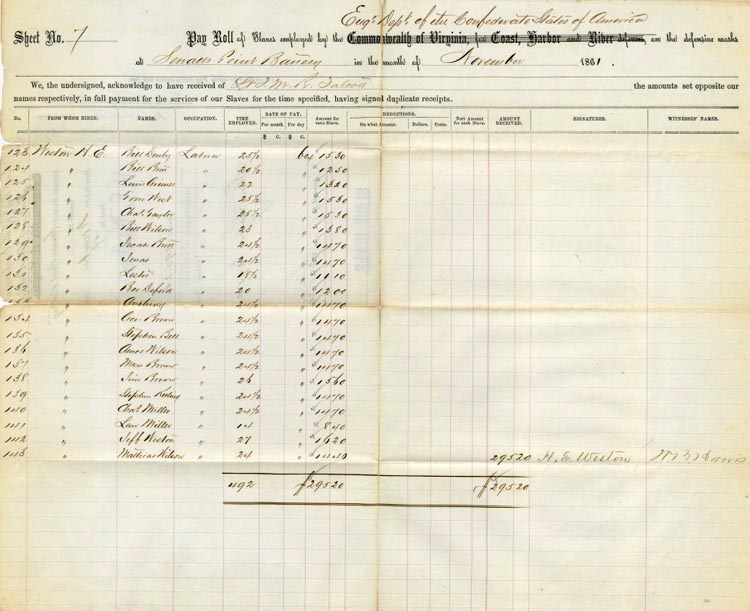

Slave Payroll 240 November 1861 Defense of Norfolk, construction of Sewell’s Point Battery

This payroll lists 17 enslaved men who are enumerated with name and surname they were enslaved to, slaveholder H.E. Westin. This payroll acknowledges that Lieutenant T. M. R. Talcott, Engineer Department, paid H. E. Weston for work performed by the following laborers (who were apparently all enslaved) at the defenses of Sewell’s Point Battery, defenses of Norfolk, Virginia, during November 1861: Bill Denby, Bill Britt, Lewis Brimes, Tom West, Charles Taylor, Bill Wilson, Jonah Britt, Jonas [no surname given], Lester [no surname given], Bev Deford, Anthony [no surname given], George Brown, Stephen Bell, Amos Wilson, Moses Brown, Jim Brown, Stephen Keeling, Charles Miller, Lew Miller, Jeff Weston, and Mathias Wilson.

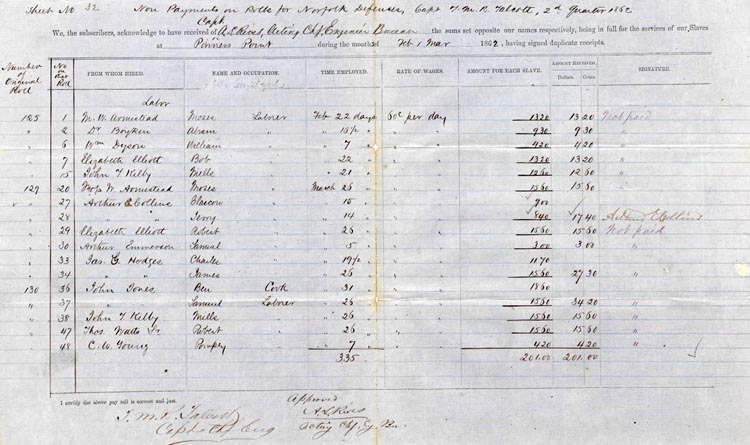

Slave Payroll number 1032 dated February and March 1862.

Defense of Norfolk: CSA Engineer Services extensively utilized enslaved workers at Pinners Point Island. On this list seventeen enslaved men are enumerated and listed by first names only. This payroll acknowledges that Captain A. L. Rives, Acting Chief, Engineer Bureau, paid certain slave owners for work performed by their slaves at Pinners Point in connection with the defenses of Norfolk, Virginia, during February and March 1862. Slaveholder M. W. Armistead (February) or Moses W. Armistead (March) provided a slave named Moses. Slaveholder Dr. Boykin provided Abram. Slaveholder William Dyson provided William. Slaveholder Elizabeth Elliott provided a Bob (February) or Robert (March). Slaveholder John T. Kilby provided an enslaved man named Mills. Slaveholder Arthur E. Collins provided two bondsmen named Glascow and Jerry. Slaveholder Arthur Emmerson provided a slave named Samuel. Slaveholder James G. Hodges provided slaves named Charles and James. Slaveholder John Jones provided enslaved man named Ben, a cook, and Samuel, a laborer. Slaveholder Thomas Watts Sr. provided an enslaved man named Robert. Slaveholder C. W. Young provided an enslaved man named Pompey.

Slaveholder Arthur E. Collins acknowledged receipt of payment for himself. The other slaveholders were not paid.

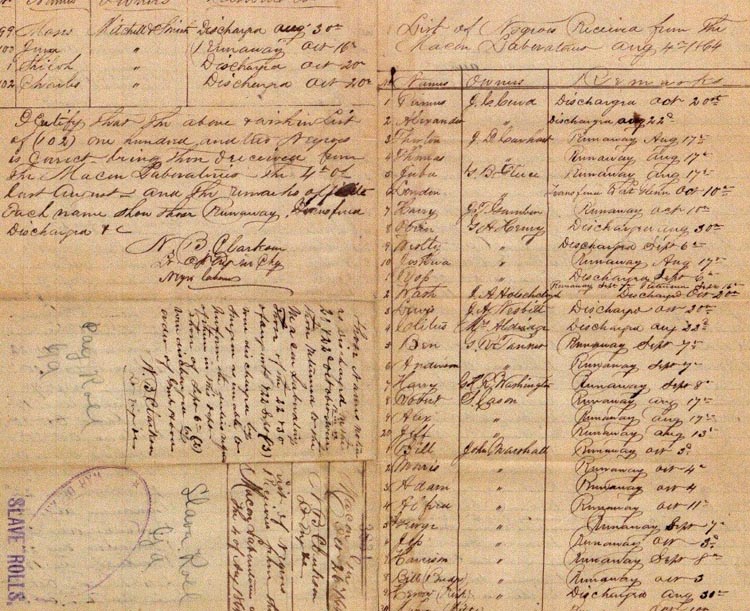

Slave Payroll 3831 (above) 4 August 1864 Macon Arsenal

Macon Arsenal AKA Macon Laboratory was a CSA munitions manufacturer, located in Macon Georgia. This facility utilized hundreds of slaves. This payroll enumerated 102 enslaved people for August 1864 and the document reflects 65 managed to flee. At peak production the Macon facility produced over 10,000 rounds of small arms ammunition and 125 artillery shells per day.10 Enslaved labor made up a large portion of the Macon Arsenal workforce. In June 1864, the Confederate army impressed twenty of the Arsenal’s enslaved laborers to dig trenches for the ultimately futile defense of Macon.11

10 Davis, Robert Scott. “A Cotton Kingdom Retooled for War: The Macon Arsenal and the Confederate Ordnance Establishment.” The Georgia Historical Quarterly, vol. 91, no. 3, 2007, pp. 266–291. JSTOR www.jstor.org/stable/40585014. Accessed 24 July 2020.

11 Davis, Ibid , 286

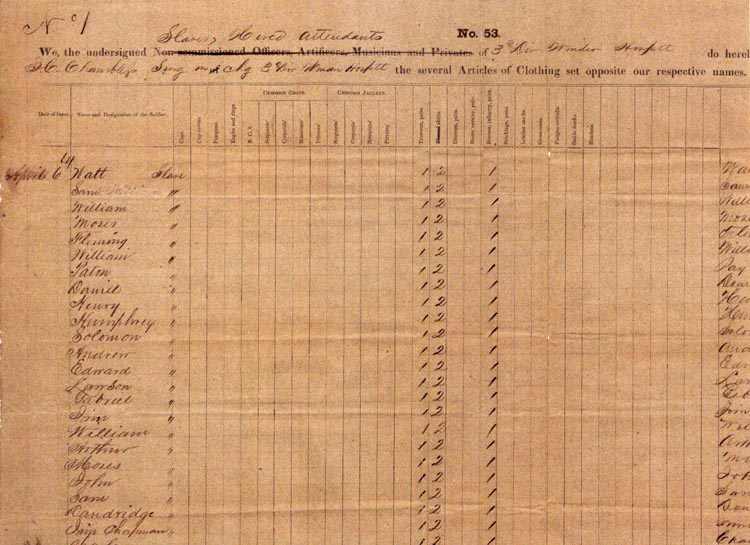

Slave Payroll for Third Division, Winder Hospital Richmond Virginia, April 186412 NARA has now begun to scan the records of Confederate military hospitals especially those in the Richmond area. In the autumn of 1861 the Confederate Congress implemented legislation that standardized the hospital system and put it under the control of the Confederate Medical Department. The city's Chimborazo Hospital, located on a hill east of the business district, became the largest in the Confederacy while also boasting one of the lowest mortality rates among hospitals in the Union and the Confederacy. At Chimborazo alone, nearly 78,000 patients were treated during the course of the war.13 One of the first hospital documents NARA placed online is from the smaller Winder Hospital (see below), which had a capacity of 5000 patients. This document dated 6 April 1864 lists 26 enslaved hospital attendants only by first name, their pay was signed for by the hospital clerk who represented the individual slaveholders.

12 Slave Payroll for Third Division, Winder Hospital Richmond Virginia, April 1864 NARA https://catalog.archives.gov/id/143509100 accessed 2 August 2, 2020

13 DeCredico, Mary and Amanda Martinez, Jaime Richmond During the Civil War Encyclopedia Virginia https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/richmond_during_the_civil_war Accessed 2 august 2020

African-American labor was paramount at Winder and to the running of all Confederate military hospitals. Though the Civil War is often thought of as the watershed that opened the field of nursing to American women, female nursing was largely a Union and not a Confederate phenomenon; 9,000 women served as nurses in Union hospitals compared to only 1,000 in Confederate hospitals, primarily because the use of hired-out male slaves in the South preempted the recruitment of white women.14

14 Leveen, Louis Richmond’s Medical Miracle New York Times, 22 November 2011 https://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/11/22/richmonds-medical-miracle/ Accessed 2 August 2002

Researchers studying Confederate slave payrolls and related documents may find additional details on the family names and location of enslaved individuals. In addition these documents may contain important information regarding slaveholders financial circumstances. See the following two examples of the information derived from slaveholder appointment of representative papers.

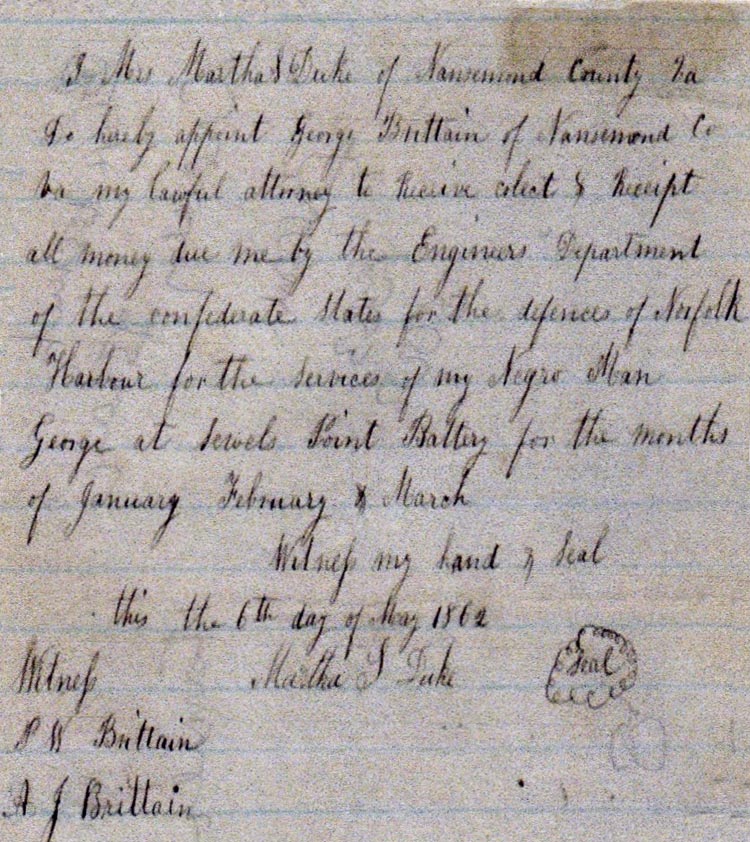

Slave payroll number 18 Slaveholder Martha S. Duke, (1828-1869) of Sleepy Hole Township, Nansemond County Virginia, signed an appointment document dated 6 May 1862 stating that Attorney George Bittain would receive and collect all wages due for her enslaved laborer George, who worked for Confederate States Engineers Department for the months of January, February and March 1862 as a "hewer" or a person who cuts wood stone or other materials for 75 cents per day, a higher rate than laborers who were paid 60 cents, however all his earnings were paid to slaveholder Martha S. Duke through her representative. Duke’s enslaved man "George” worked on the defense of Norfolk Harbor at Sewell’s Point Battery.

The 1860 Slave Census reflects Martha S. Duke was enumerated with six enslaved persons , these included one, male age 65, one male age 36 ("George"), and five females ages 16, 6, and 1. The 1860 census show here property included real estate valued at $1200.00 and $3,500.00 in "personal property" almost certainly the enslaved individuals.

Slave payroll number 7, this appointment receipt dated 7 April 1862 shows slaveholder Joel M. Tartt, (1810 to after 1865) of Norfolk County Virginia, appointed attorney T.R. Wise of Norfolk as his agent to receive and collect all wages due for enslaved men "Simon" (Simon Tart) and "George" (George Tart). Both enslaved labors worked for the Confederate government at 60 cents per day building defensive works at Craney island as part of the defense of Norfolk, during the month of February 1862. Tartt was probably born in 1810 as the 1860 U.S. Census stated his age as 50. Tartt’s occupation is listed as farmer, and his estate valued at $11,100.00 while his personal property which included all enslaved persons is valued at $5,260.00. The 1850 Slave Census enumerated Tartt as a slaveholder, with eight enslaved individuals working on his property. The enslaved males are listed ages 40, 33, 16 and 10. Enslaved females are enumerated as ages 32, 30, 12 and 10.

* * * * * * * * * *

John G. "Jack" Sharp resides in Concord, California. He worked for the United States Navy for thirty years as a civilian personnel officer. Among his many assignments were positions in Berlin, Germany, where in 1989 he was in East Berlin, the day the infamous wall was opened. He later served as Human Resources Officer, South West Asia (Bahrain). He returned to the United States in 2001 and was on duty at the Naval District of Washington on 9/11. He has a lifelong interest in history and has written extensively on the Washington, Norfolk, and Pensacola Navy Yards, labor history and the history of African Americans. His previous books include African Americans in Slavery and Freedom on the Washington Navy Yard 1799 -1865, Morgan Hannah Press 2011. History of the Washington Navy Yard Civilian Workforce 1799-1962, 2004.

https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/browse-by-topic/heritage/washington-navy-yard/pdfs/WNY_History.pdf

and the first complete transcription of the Diary of Michael Shiner Relating to the History of the Washington Navy Yard 1813-1869, 2007/2015 online:

https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/d/diary-of-michael-shiner.html

His most recent work includes Register of Patients at Naval Hospital Washington DC 1814 With The Names of American Wounded From The Battle of Bladensburg 2018,

https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/r/register-patients-naval-hospital-washington-dc-1814.html

The last three works were all published by the Naval History and Heritage Command. John served on active duty in the United States Navy, including Viet Nam service. He received his BA and MA in History from San Francisco State University. He can be reached at sharpjg@yahoo.com

* * * * * * * * * *

Norfolk Navy Yard Table of Contents

Birth of the Gosport Yard & into the 19th Century

Battle of the Hampton Roads Ironclads