Introduction: The following is a transcription of a long forgotten but important memorandum by Commodore Lewis Warrington for the Secretary of the Navy in which he provided the number of enlisted men entered into the U.S. Navy during the period subsequent to 1 September 1838. The memorandum itself was compiled and dated September 17, 1839 probably by the officers of the receiving ship Java, then stationed at Norfolk Virginia. The document breaks out the number of men entered from five naval recruitment stations at Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Norfolk.1 Remarkably for this time period, and of great importance to scholars, the actual number of black men who were entered into the navy is given both as a total, and is specified for each naval station.

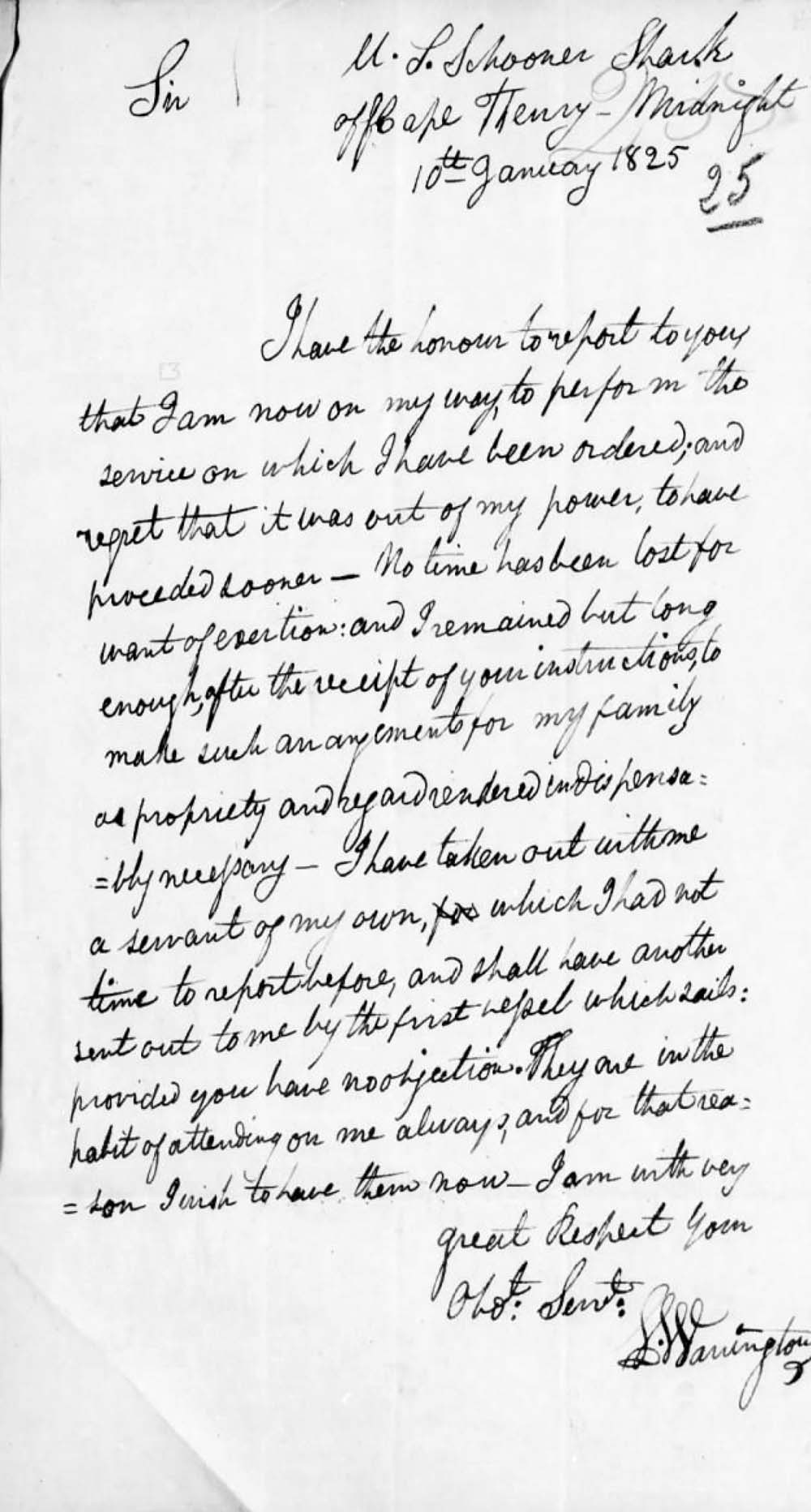

Background: On 13 September 1839, acting Secretary of the Navy, Isaac Chauncey issued a circular declaring that in view of complaints, the number of blacks in the naval service, there would henceforth be no more than 5 percent of the total number entered under any circumstances and no slave was to be entered under any circumstances.2 One of the complaints was from Commodore Lewis Warrington, Commandant of Gosport Navy Yard.3 Warrington the son of a wealthy slaveholding Virginia family; like many of his caste was used to having his bondsmen attend on him. In 1825 he had requested permission of the Secretary of the Navy to take his slaves aboard explaining “I have taken out with me a servant of my own, for whom I had not time to report before, and shall have another sent out to me by the first vessel which sails provided they have no objection. They are in the habit of attending on me always and for that reason I wish to have now.”4 In 1826 as Commandant of the Pensacola Navy Yard he had written to the Secretary of the Navy “neither laborers nor mechanics are to be obtained here.”5 While Warrington was able to get skilled white journeymen from Norfolk; he requested and received permission to hire slaves locally. The Pensacola payrolls, like those at Norfolk Navy Yard reveal the Navy rented slaves from prominent members of society and such rental actions by the federal governments directly helped expand enslaved labor in Florida and Virginia as local owners could look forward to a regular and steady income. Some idea of the human scale of slavery at Norfolk can be found in a letter dated 12 October 1831 from Warrington to the Board of Navy Commissioners in response to various petitions by white workers. His letter attempts both to reassure the Board, in light of the recent led by Nat Turner, slave rebellionner, which occurred on 22 August 1831, and to serve as a reply to the dry dock's stonemasons who had quit their positions and accused the project chief engineer, of the unfair hiring of enslaved labor in their stead.

There are about two hundred and forty six blacks employed in the Yard and Dock altogether; of whom one hundred and thirty six are in the former and one hundred ten in the latter – We shall in the Course of this day or tomorrow discharge twenty which will leave but one hundred and twenty six on our roll – The evil of employing blacks, if it be one, is in a fair and rapid course of diminution, as our whole number, after the timber, now in the water is stowed, will not exceed sixty; and those employed at the Dock will be discharged from time to time, as their services can be dispensed with – when it is finished, there will be no, occasion for the employment of any.6 Slavery would continue on at the Pensacola and Norfolk until the Civil War.7

During the late 1830’s critics of slavery, became more vocal; one of these was William McNally, an ex-Navy gunner’s mate. In 1839 McNally, published a widely read expose of the naval and merchant service Evils and Abuses in the Naval and Merchant Service Exposed; with Proposals for their Remedy and Redress. McNally charged, that naval officers countenanced and profited from slaves employed on naval vessels and in the navy yards as laborers “to the exclusion of white people and free persons of color.”8 McNally was a former crewman on the USS Java and alleged that he witnessed, enslaved blacks hired on as seamen, with slaveholding officers receiving their wages. He also charged that the same practices existed in naval shipyards to the detriment of free whites and black laborers. Here McNally specifically referred to Norfolk Navy Yard, where he had served in the 1830’s. McNally’s charges may have prompted the Navy Department to issue the new regulations. In his 21 June 1839 letter to Secretary of the Navy James K. Paulding; Warrington denied that navy yard slaves were owned by naval officers but confirmed “that many” were owned and rented to the yard by the master mechanics and workmen: “I beg leave to state, that no Slave employed in this Yard, is owned by a commissioned officer, but that many are owed by the Master Mechanicks & workmen of the Yard”9

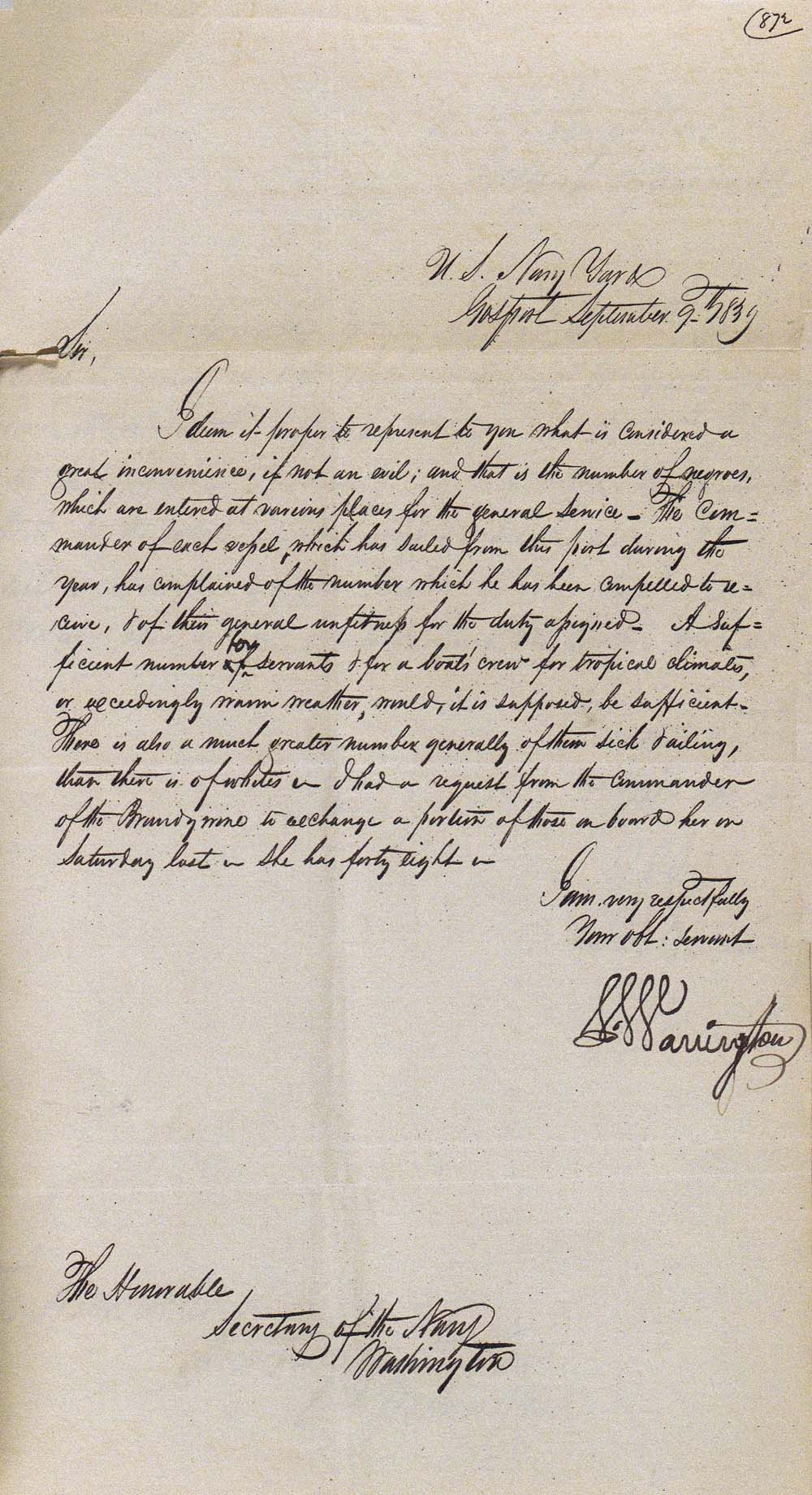

Despite his firm support for enslaved labor, Warrington’s attitude toward free blacks as reflected in his 9 September letter to Paulding was unequivocal; the Nat Turner rebellion had shaped his views, he did not want free blacks aboard ship or working in the shipyards.10 Like many slaveholders Warrington remained apprehensive of free blacks whom he described as “a great inconvenience if not an evil.” Warrington allowed for black seamen but only “A sufficient number of boy servants & for a boats crew for the tropical climate or exceedingly warm weather…” though it is clear from the tone he favors a drastic reduction in the numbers of black seamen. As a follow- up on 19 September 1839, Warrington provided Paulding with “the number of coloured person, entered on the different stations, since the 1st of September of the last year -” which he enclosed as “A Memorandum of Recruits Recd from the Several Naval Stations Subsequently to 1st Sept. 1838”11

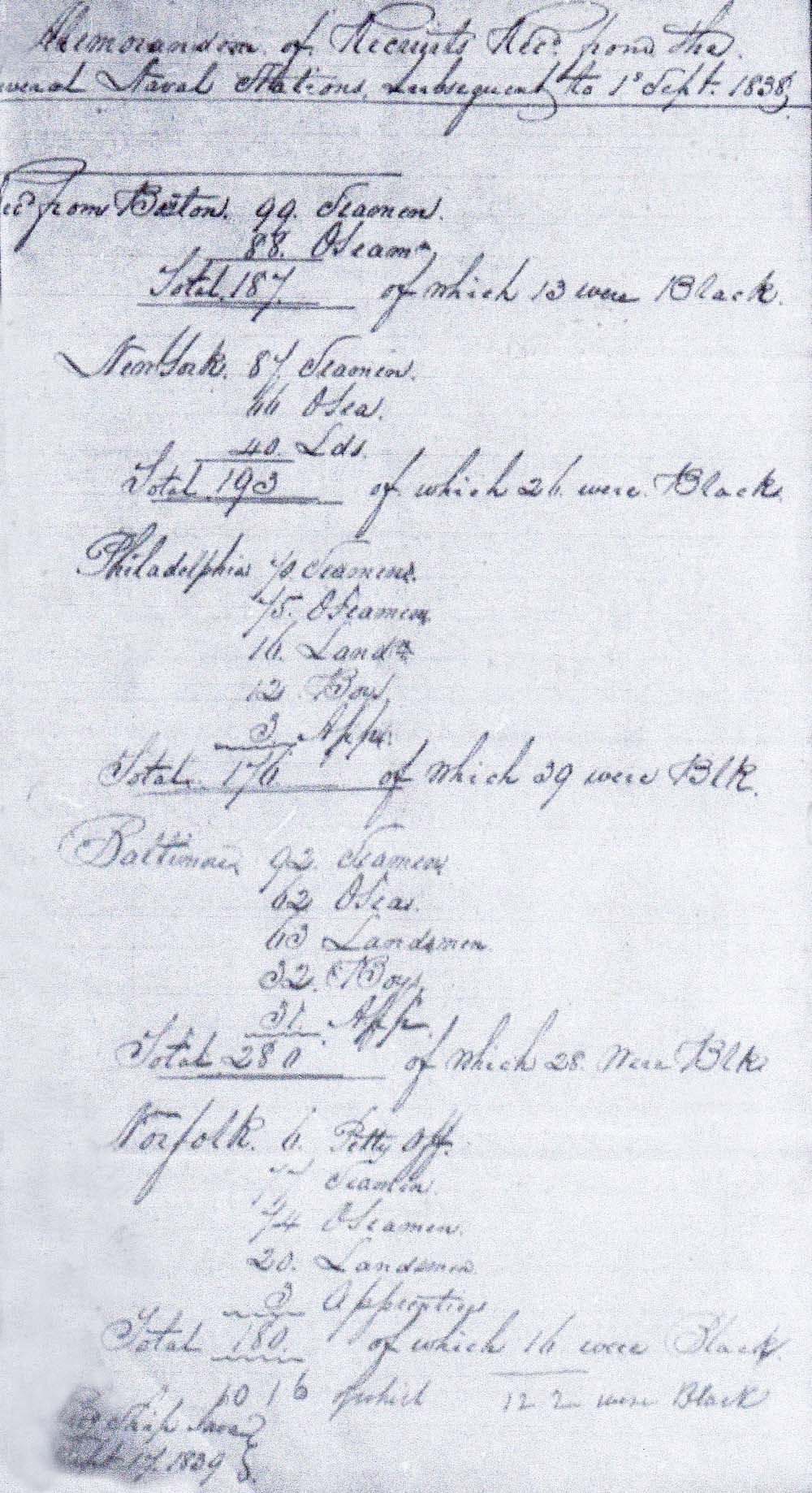

This document was compiled at the direction off Commodore Warrington to provide recruitment data for the Secretary of the Navy on the number of black seamen recruited for over a one year period at five naval recruiting stations. A note in the lower left margin of the memorandum gives the date as “ Recg Ship Java Sept 1839.” The frigate USS Java was stationed in Norfolk Harbor, where she served as a receiving ship; to house newly recruited sailors before they are assigned to a ship's crew from 1831 until 1842. Despite Warrington’s critical stance on black sailors, the memorandum provides a useful picture their presence within the U.S. Navy. As such this document is unique in the antebellum period and vital to any understanding of the era. During these decades there was no career centralized enlisted service; and with rare exceptions nothing much else exists in the way of reliable statistical information beyond the occasional private letter or anecdotal recollections.12 Crew payroll records and muster lists of 1830’s make almost no reference to people of color. Consequently the data Warrington collected from the five recruitment stations located in Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore and Norfolk is invaluable.13

Method and Limitations: Warrington’s memorandum covers recruits from 1 September 1838 to September 17, 1839. The document provides data for five naval recruiting stations which in total entered 1016 men for naval service, “of which 122 were Black” or 12% of the total. How the data was actually collected is not stated, most likely the Commodore simply requested the data from the receiving ship officer. The document however does reveal which naval stations had greatest levels of blacks entering the service. Philadelphia had the highest level, for they entered a total of 176 men, “of which 39 were Blk” for 22.1 % of the total. The Boston recruiting station entered the least with 187 men “of which 13 were Black” for 6.95 % of the total. The New York station recruited 193 men total “of which 26 were Black” for 13.47% of the total, while Norfolk station recruited 180 men total “of which 16 were Blk” or 8.89% of total, and the Baltimore station recruited 280 men of which 25 were Blk” or 8.93% of the total. For modern readers, definition of “black” is absent, a decision Warrington undoubtedly left to the discretion of the station recruiting officers. Likewise the document has no real information as to how many blacks entered in each rank, such as: Landsmen, Ordinary Seamen or Seamen, etc. Notwithstanding these limitations Commodore Warrington’s 1839 memorandum provides significant new insights and reliable data.

John G. Sharp, 6 February 2019Abbreviations: The following are some of memorandum’s notable abbreviations. Landsmen is abbreviated “Lds”, Landsmen were the lowest rank of the United States Navy in the nineteen century. Landsmen were almost always new recruits with little or no experience at sea and typically performed menial, unskilled work aboard ship. A Landsman who gained three years of experience or re-enlisted could be promoted to Ordinary Seaman. The rank existed from 1838 to 1921. Next is, Ordinary Seaman is abbreviated “O.S.” or “OSea” the second-lowest rank of the nineteenth century. This was the U.S. Navy ranking above Landsman and below Seaman. Promotion from Landsman to Ordinary Seaman normally required three years of experience or re-enlistment or had prior service in the merchant marine. An ordinary seaman who gained six years of life at sea and “knew the ropes”, that is, knew the name and use of every line in the ship’s rigging could be promoted to seaman. An Ordinary Seaman’s duties aboard ship included “handling and splicing lines, and working aloft on the lower mast stages and yards. Seamen were enlisted men who had served at least three years and were experienced in most of the stations found aboard a naval vessel such as the helm, sea and anchor detail, gunnery and had shown proficiency in working sails. Apprentices is abbreviated “App”, apprentices were boys, between the ages of 12 -18 who were in training and usually promoted to Ordinary Seaman on reaching maturity. Lastly as a rank the “Petty Officer “ was between naval officers (both commissioned and warrant) and most enlisted sailors. Petty officers usually were men with years of experience working with the ship’s boatswain mate and quartermaster, or as a clerk to the captain or the purser.

Transcription: This transcription was made from digital images of letters and documents received by the Secretary of the Navy, NARA, M125 “Captains Letters” National Archives and Records. In transcribing all passages from the letters and memorandum, I have striven to adhere as closely as possible to the original in spelling, capitalization, punctuation, and abbreviation, superscripts, etc., including the retention of dashes and underlining found in the original. Words and passages that were crossed out in the letters are transcribed either as overstrikes or in notes. Words which are unreadable or illegible are so noted in square brackets. When a spelling is so unusual as to be misleading or confusing, the correct spelling immediately follows in square brackets and italicized type or is discussed in a foot note.

===================================

U.S. Navy Yard Gosport

September 9th 1839

Sir, I deem it proper to represent to you what is a considered a great inconvenience if not an evil; and that is the number of negroes which are entered at various places for the general Service – The commander of each vessel, which has sailed from this port during the year, has complained of the number which has been compelled to receive, & of their general unfitness for the duty assigned – A sufficient number of boy servants & for a boats crew for the tropical climate, or exceedingly warm weather, would, it is supposed be sufficient. There is a much greater number of them generally sick & ailing, than there is of whites – I had a requested from the commander of the Brandywine to exchange a portion of those on board her on Saturday last – She has forty eight – I am very respectfully your obedient Servant L Warrington

[To] The Honorable Secretary of the NavyU.S. Navy Yard

Gosport September 19th 1839

Sir,

Conformably to your letter of the 13th, which I had the honor to receive on the 16th, I forward the number of Coloured persons, entered at the different stations, since the 1st of September of the last year – Presuming you would like to see the proportion of them, to the whole number extended at each place. I have made the list accordingly; viz: at Boston 14 or /15, at New York 7/26, at Philadelphia, 4 20/19 at Baltimore, one tenth, at Norfolk 11 ¼ -

I am very respectfully

Your obt. Servant

L.Warrington

[To] The Honorable Secretary of the Navy Washington[Enclosure]

Memorandum of Recruits Recd from the Several Naval Stations, Subsequent to 1st Sept. 1838

Report from:

Boston 99 Seamen

88. OSeamn

Total 187 of which 13 were BlackNew York 87 Seamen

66 O Seamn

40 Lds.

Total 193 of which 26 were Black

Philadelphia 70 Seamen

75 O Seamen

16 Landn

12 Boys

3 App

Total 176 of which 39 were Blk

Baltimore 92 Seamen

62 Osea

62 Landsmen

32 Boys

31 App

Total 280 of which 25 were Blk

Norfolk 6 Petty off

77 Seamen

74 OSeamen

20 Landmen

3 Apprentices

Total 180 of which 16 were Black

1016 of which 122 were Black

Recg Ship Java )

Sept.17 1839

[End Document]===================================

Endnotes

1 The USS Java was built at Baltimore, Maryland, in 1814 and 1815 by Flannigan & Parsons. Completed after the end of the War of 1812, the new frigate departed from Newport 22 January 1816 in the face of a bitter gale. At sea one of her masts snapped with ten men upon the yards, killing five. Java was off Algiers in April where Perry went ashore under a flag of truce and persuaded the Dey of Algiers to honor the treaty which he had signed the previous summer but had been ignoring. Next she sailed for Tripoli with Constellation, Ontario, and Erie to show the strength and resolve of the United States. Then, after a cruise in the Mediterranean stopping at Syracuse, Messina, Palermo, Tunis, Gibraltar and Naples, the frigate returned to Newport early in 1817 and was laid up at Boston, Massachusetts. Java returned to active service in 1827 under Captain William M. Crane for a second deployment in the Mediterranean. There she protected American citizens and commerce and performed diplomatic duties. Toward the end of the cruise she served as flagship of Commodore James Biddle. After returning to the United States in 1831, Java became receiving ship at Norfolk, where she was broken up in 1842.2 Acting Secretary of the Navy Isaac Chauncey Circular, September 13, 1839, Circulars and General Orders, I, 357

3 Commodore Lewis Warrington USN was born in Williamsburg Virginia on 3 November 1782. He briefly attended William and Mary College prior to be appointed as Midshipman USN in 1800. Warrington served in the Quasi War with France, the Barbary Wars and the War of 1812. During the war he quickly established a reputation as brave and resourceful officer and in 1814 received a gold medal from the U.S. Congress for his heroic conduct. In 1825, Warrington served as one of three commissioners on a panel charged with selecting a site on which to establish a new South Atlantic fleet. The panel selected Pensacola, Florida and Warrington was ordered to Pensacola where he was charged with overseeing the construction of a new navy yard and leading the West India Squadron. As the first commandant of the Pensacola Navy Yard, he established the village of Warrington for his white workers, and gave it his name. In 1829, Lewis Warrington was returned to Norfolk for a decade as commandant of the Norfolk Navy Yard. He later temporarily served as the Secretary of the Navy. Warrington died on 12 October 1851 and is buried at Congressional Cemetery.4 Warrington to Samuel Southard 10 January 1825 NARA M125 “Captains Letters” 1 Jan 1825 -18 Feb 1825 , letter number 25

5 Warrington to the Board of Navy Commissioners 27 April 1826

6 Warrington to Board of Navy Commissioners 12 October 1831 NARA RG45

7 Ernest F. Dibble Antebellum Pensacola and the Military Presence, (University of West Florida: Mayes Publishing 1974), 67. For Norfolk Navy Yard see Robert S. Starobin, Industrial Slavery in the Old South, (Oxford University press: New York third edition 1972), 32.

8 William McNally Evils and Abuses in the Naval and Merchant Service Exposed; with Proposals for their Remedy and Redress (Cassidy and March: Boston1839 ), 127 See also Harold D. Langley Social Reform in the United States Navy 1798 -1862 University of Illinois: Chicago 1967) 93

9 Warrington to Paulding 21 June 1839 NARA M125 “Captains Letters” 1 June 1839 -30 June 1839, letter number 77

10 Warrington to Paulding 9 September 1839 NARA M125 “Captains Letters” 1 Sept 1839 -30 Sept 1839, letter number 38

11 Warrington to Paulding 19 September 1839 NARA M125 “Captains Letters” 1 Sept 1839 -30 Sept 1839, letter number 58, 1-3

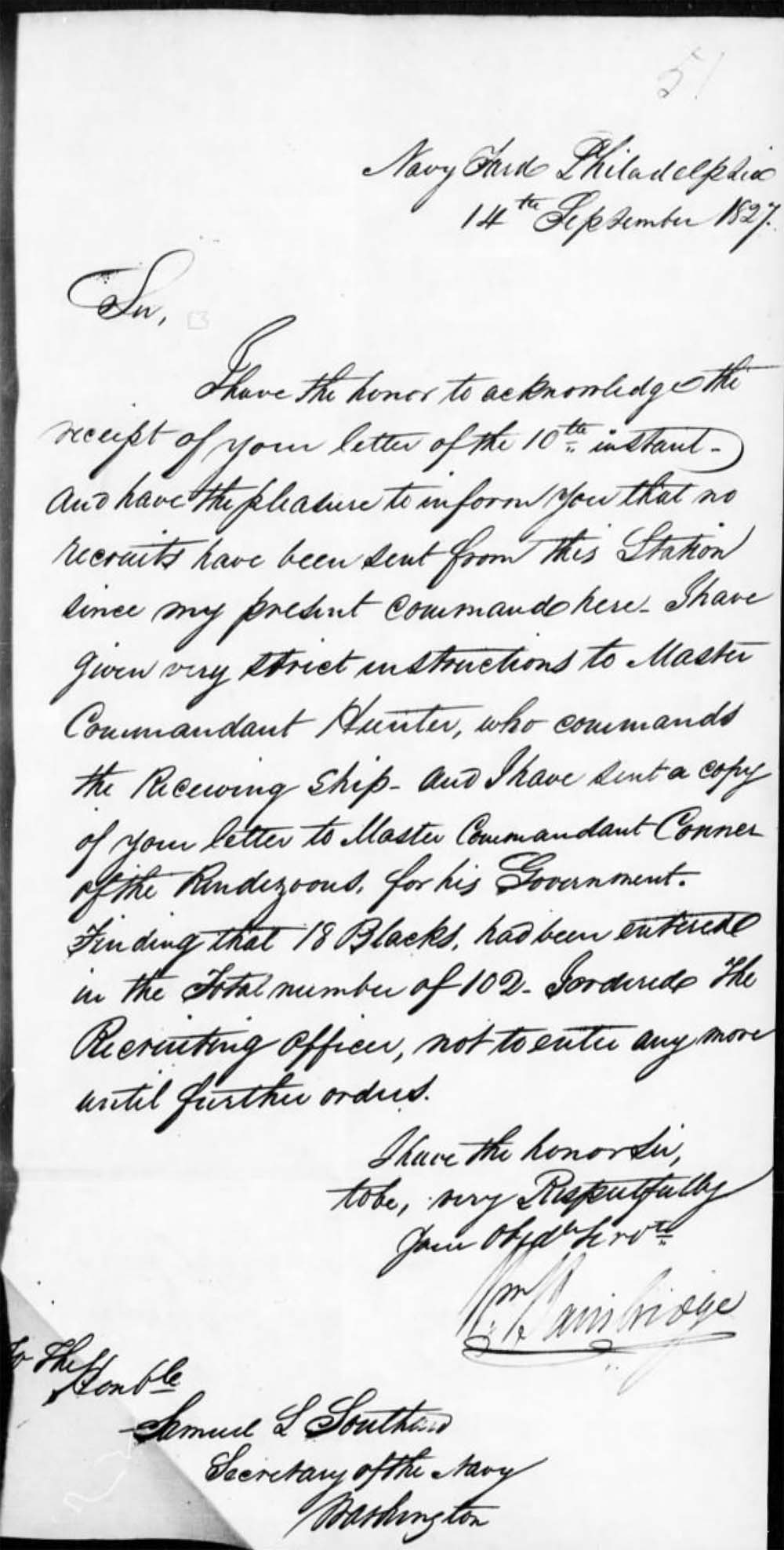

12 William Bainbridge to Southard 14 September 1827 NARA M125 “Captains Letters” 30 July 1827 – 6 Oct 1827, letter 51. Bainbridge writes, “Finding that 18 Blacks had been entered in the total number of 102. I ordered the Recruiting officer, not to exceed any more until further orders.”

13 Harold D. Langley “The Negro in the Navy and Merchant Service--1789-1860 ” The Journal of Negro History, vol. 52, no. 4, 1967, 274 JSTOR,

https://www.jstor.org/stable/2716189?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contentsARCHIVES

1 Lewis Warrington letter September 9, 1839, #10 & 11 endnotes

2 Memorandum of receipts received from several naval stations subsequent to September 1, 1838

3 September 14, 1827, Letter from Navy Yard in Philadelphia, #12 endnote

4 Lewis Warrington letter January 10, 1825, #4 endnote

John G. “Jack” Sharp resides in Concord, California. He worked for the United States Navy for thirty years as a civilian personnel officer. Among his many assignments were positions in Berlin, Germany, where in 1989 he was in East Berlin, the day the infamous wall was opened. He later served as Human Resources Officer, South West Asia (Bahrain). He returned to the United States in 2001 and was on duty at the Naval District of Washington on 9/11. He has a lifelong interest in history and has written extensively on the Washington, Norfolk, and Pensacola Navy Yards, labor history and the history of African Americans. His previous books include African Americans in Slavery and Freedom on the Washington Navy Yard 1799 -1865, Morgan Hannah Press 2011. History of the Washington Navy Yard Civilian Workforce 1799-1962, 2004.

https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/browse-by-topic/heritage/washington-navy-yard/pdfs/WNY_History.pdf

and the first complete transcription of the Diary of Michael Shiner Relating to the History of the Washington Navy Yard 1813-1869, 2007/2015 online:

https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/d/diary-of-michael-shiner.html

His most recent work includes Register of Patients at Naval Hospital Washington DC 1814 With The Names of American Wounded From The Battle of Bladensburg 2018,

https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/r/register-patients-naval-hospital-washington-dc-1814.html

The last three works were all published by the Naval History and Heritage Command. John served on active duty in the United States Navy, including Viet Nam service. He received his BA and MA in History from San Francisco State University. He can be reached at sharpjg@yahoo.com

Norfolk Navy Yard Table of Contents

Battle of the Hampton Roads Ironclads