|

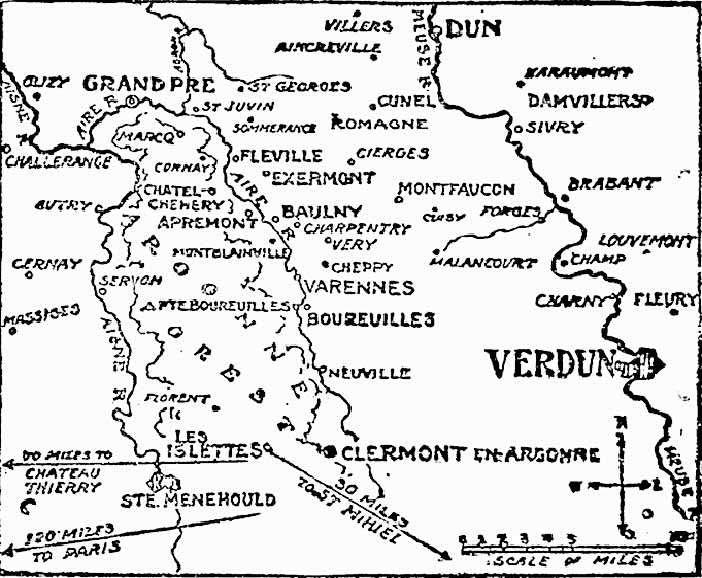

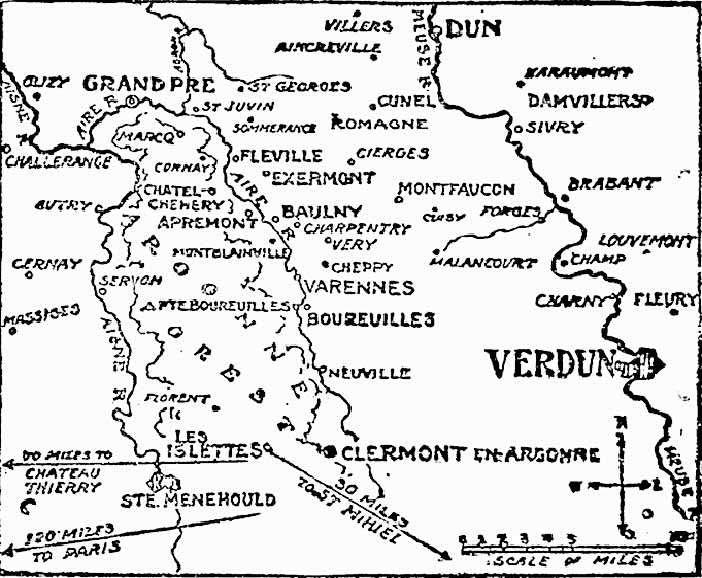

A History of Pittsburg and Western Pennsylvania Troops in the War

By John V. Hanlon (Copyright 1919 by The Pittsburg Press)

Chapter XVI

(The Pittsburg Press, Sunday, April 20, 1919, pages 82-83)

Names in this chapter: Pollock, Dove, Earls, Brain, Halsey, Brosius, Hewitt,

Shafer, Books, Gray, Herdman, Smith, Bienna, Townsend, Gilham, Timmor, Thompson,

Caster, Cope, Strong, Kellerman, Bax, Maag, Herrig, Schedemantel, Semanchuch,

Hanley, Scheidmantel, Rollins, Scheider, Killinger

No person who was not there and participated in the battles can have anything

but a hazy idea of the dangers and privations which the American doughboys faced

almost daily when engaged in breaking the German military machine. And our

Pittsburg and Western Pennsylvania soldiers were always found to be in the thick

of the most severe fighting for the high officers knew they could be depended

upon to thoroughly and effectually perform whatever tasks they were assigned.

THE EIGHTEITH DIVISION PERFORMED WONDERFUL WORK IN THE GREAT ARGONNE-MEUSE

OFFENSIVE AS PART OF THE FIRST AMERICAN ARMY. MANY OF OUR BOYS WERE KILLED AND

WONDED BY BOCHE SHELLS EVEN BEFORE THEY REACHED THE FRONT LINE TRENCHES BECAUSE

THE BACK AREAS WERE ALMOST CONTINUALLY UNDER A RAIN OF GAS, SHRAPNEL AND HIGH

EXPLOSIVE SHELLS. THE MEN OF THE EIGHTIETH PERFORMED NOBLY THROUGHOUT THAT

TERRIBLE DRIVE AND BY THEIR DARING AND BRAVERY WON A HIGH PLACE IN THE LIST OF

THE FOREMOST AMERICAN DIVISIONS OF THE WAR.

In presenting this story of the activities of the

Eightieth division The Press has been fortunate in securing a copy of the diary

of Corp. Arthur Nelan Pollock, Co. F, Three Hundred and Twentieth infantry,

whose home address is 614 Wallace ave., Wilkinsburg, and who carefully jotted

down the events from day to day in the great Argonne-Meuse offensive. Perhaps no

more faithful record of this great battle and the work of the Pittsburgh and

Western Pennsylvania men who made up a large part of this division could have

been obtained, for it comes from a man in the ranks who was actively engaged out

on the very brink of that far-flung battlefront and who was gifted with the

facility of observing and recording the swiftly moving panorama of that

stupendous occasion. It is a wonderful, gripping story simply, and

intelligently, and thoroughly told, and it is intimate, for it concerns our

boys.

Future histories of that wonderful drive by the First

American army through a German stronghold reputed to be impregnable will no

doubt give more detail in dealing with the operation from a military viewpoint,

but they will not tell of the daily grind of the sons whom the fathers and

mothers of Pittsburg and Western Pennsylvania sent into that contest for the

freedom of the world, and of their achievements. Corp. Pollock’s diary covers

the work of our soldiers from day to day; of their dangers and their privations

and even amidst that awful carnage with death stalking on every hand; with

throats parched with thirst; with stomachs crying out because of the gnawing

pains of hunger; with their bodies weakened from incessant strife in the

daylight hours and slumberless nights they still found time for humor and to

laugh, and best of all, to “carry on.”

Corp. Pollock and these lads of whom he speaks were one

of the big factors in breaking the backs of the German military machine; that

mighty mechanism which had almost crashed its way through to Paris, the sea, and

victory before America answered with her unconquerable legions; those wonderful

legions whose glittering steel withered the most famous of the kaiser’s

regiments and cut them down like wheat before the reaper’s blade.

Here is Corp. Pollock’s story as he set it down

whenever he had a moment’s respite and while the events were fresh and indelibly

stamped in his memory:

“On September 24 about 5 p.m., near Lampere, we rolled full packs and in

addition to the Chant Chat automatic rifle I had two bombs, one hundred rounds

of ammunition in my belt and two bandoliers of 60 rounds each. At 6 o’clock we

had our supper of beef stew, bread, jam, Karo and coffee. On this date we

received semi-automatic pistols of 45 caliber. Our iron rations or emergency

rations consisted of four boxes of crackers known as hard bread and one can of

corned beef. At 7 p.m. we started on a 12 kilometer march toward the front. On

this march we passed the great Verdun cemetery where two millions soldiers are

buried of which over one million are German, the balance soldiers of the allies.

When near Germanville the Hun started to shell the road we were marching on and

we put on our helmets. We marched through Germanville and up a long hill to the

trenches and dugouts in the woods northeast of the village. Here we were about

six kilometers from the front line with French heavy artillery all around us,

some of it capable of firing 18 kilometers. We arrived here shortly after

midnight. F. Kirks Earls and I did not pitch tents but just rolled up in our

blankets and shelter halves. For the first and only time in my life I slept with

a pistol under my head. All night the Huns were firing shells over our heads

into the town we had come through earlier in the evening, and how we hoped they

would not shorten their range.”

SHELLS KILL MANY

“On Sept. 25 we got up at 6 a.m. It was a very pretty

morning and the weather was fine. We had breakfast at 8 a.m. and Earls and I

cleaned our automatic pistols and rifles, pitched our tent, and visited dugout

No. 6 which had been assigned to “F” company in case of an emergency. The main

stairway down was 50 feet deep. One room at the foot of the stairs was fitted up

with bunks and there was also on this floor a fully equipped power plant for

lighting the whole series of dugouts. About halfway down the stairs there was

also another large room equipped with bunks. Electric lights were used

throughout.

“At 2 P.M. we had dinner – beef stew, potatoes, bread

and coffee. At 3 p.m. Capt. Maag gave us a lecture on the use and care of the

pistol. At 5:30 p.m. we had supper, then the company was assembled and a

bulletin was read telling of the good behavior of the men while in training and

their determination to do their bit, and that now as the time had come to fight

they were to show the same determination to win and fight to the end. Later, we

put our rations and toilet articles in one small pack and fixed up all our other

belongings in a roll and at 9 p.m. lined up at the kitchen wagon for another

meal, this time – beans, bread, syrup and coffee.

“I had just left the wagon with my mess kit full when

Jerry dropped a shell not 50 feet from me. It hit our lumber or supply wagon for

the kitchen, smashing it all to pieces and throwing our eats everywhere. He

dropped quite a few shells there among us in the next few minutes, killing and

wounding many of our regiment. We ran to dugouts and stayed there until things

quieted down a little, then formed on the road preparatory to leaving the woods.

“While forming the shelling continued. One struck a

tree by the road a glancing blow and the shell came rolling down the road not

three feet from me, but it was a ‘dud’ and did not explode. It was an awful

sensation to lie there (I was in a ditch or gutter beside the road), and hear

the boom of the shell as it left the German gun, then the whistling as it came

toward us (more like a who-o-oo-oo-oop) and the bang as it burst around us, then

the pitiful cries in the dark for help and first aid. Later we heard there were

11 killed and 31 injured while we were in this position.

MILLION DOLLAR BARRAGE

“We left about 11 p.m. on a six kilometer march for

Bethicourt. As we left the greatest barrage the world has even known started.

‘The million dollar barrage’ it is called and it lasted for 12 hours. Had all

the cannon used in this barrage been placed in line hub to hub, the length of

the line thus formed would have been longer that the entire battle front in

Europe. It was about 4 a.m. when we were deployed and ready for the word

‘Forward’ over the top in ‘No Man’s Land.’ We rested until 5:03 a.m. The Fourth

division regular army was on our left and the Three Hundred and Nineteenth

infantry on our right. ‘G’ and ‘H’ companies were in the first wave and ‘F’ and

‘E’ companies were ‘moppers up.’ The Three Hundred and Fifth engineers were with

us carrying rifles on one shoulder and sections of bridges on the other. The

Second battalion was covering a two kilometer front. The First and Third

battalions were in support and the Three Hundred and Seventeenth infantry was in

reserve for the Three Hundred and Twentieth and Three Hundred and Eighteenth was

in reserve for the Three Hundred and Nineteenth infantry. The great barrage was

put over for our division by the Thirty-third and Eighty-second division

artilleries. There were about 600,000 Americans and 300,000 French soldiers

engaged in this drive. (Private Killinger was killed in the woods at Germanville.)

“At 5:030a.m. on Sept. 26, was the ‘zero hour.’ The

noise made by the cannon and machine guns behind us was terrific. You couldn’t

hear the man next to you, but then he was about 15 feet away in this combat

formation. The fog and smoke was so dense, too, that one could hardly see the

next man although the sun was slowly coming up. Soon after we started Sergt.

Halsey was shot in the neck and spit the bullet out of his mouth, dying later.

In the confusion the smell of smoke and powder was mistaken for gas and gas

masks were put on.

“As we charged down the hill through the smoke, fog,

and barbed wire entanglements with our masks on, we soon found ourselves in the

cellars and ruins of buildings which the retreating Huns had left burning. Our

squad had become detached from the rest of the company. After removing our masks

we attempted to locate our company. Hearing familiar whistles to our right and

ahead of us we double-times it in that direction and attached ourselves to Co. C

of the Three Hundred and Nineteenth infantry which was in the front line of

assault. So far our progress had all be down hill, and now as we charged up hill

the fog lifted and we could see the work our artillery was doing. The whole side

of the hill was filled with shell holes, some 15 feet in diameter and nearly as

deep. Barbed wire entanglements had been torn all to pieces and trenches and

dug-outs blown up.

IT WAS UP-HILL WORK

“In spite of the great noise made by our artillery in

the rear we could hear the German machine guns in front of us, and advanced up

the hill by jumping from shell-hole to shell-hole. Sometimes the shells would

destroy the home of a jack rabbit, and how he would go jumping across No Man’s

Land. Pretty soon a German popped up out of a trench ahead of us with his hands

up and yelled ‘Kamerad.’ As no one fired at him he came toward us asking which

way to go. Someone behind me told him New York was back in the rear, and away he

went in that direction on the double, hands up all of the time.

“I wasn’t advancing very fast, for the Jerries must

have seen my automatic. Anyway when I wasn’t in a shell-hole they were making it

pretty warm for me and the bullets were singing around my helmet at a great

rate. Finally I made a dash the rest of the way up the hill and into their

trench. There they were, two youngsters, one looked a lot like Frank Brosius and

neither one looked a bit older. Both were crying ‘Kamerad.” The German machine

gun is a water cooled affair and we had come upon them so swiftly, they hadn’t

had time to connect it up but had fired it until it was so hot it wouldn’t fire

anymore.

“I searched my prisoners and as they had no arms I

destroyed their machine gun and showed them the way back to the cage. You can

understand why a guard is not sent back with two or three men when I tell you

that about ever three or four hundred yards there were lines of soldiers

following the front line. Over on my right there was a great deal of cheering

and yelling. The boys had captured a dug-out in the same trench and 27

‘square-heads’ as we called them. They were filing out to be searched and

started to the rear; some old men, some boys, but all appearing to be well-fed.

A lot of ammunition and some German grub were captured in the trench. I might

say right here that later reports showed that 1,500 prisoners had been captured

in the first half hour of the battle. This is a pretty good record considering

that we occupied only two kilometers of the one hundred kilometer front.

“Then we went ‘over the top’ again and forward to the

next German trench, leaving the ‘moppers-up’ to get all the Germans out of the

dug-outs and take captured material back. The machine guns continued to fire on

us and quite a few of our comrades were being wounded, but there were a great

many of dead and wounded Germans lying around also. Before we reached the next

trench a long string of Jerries came out toward us with hands up; some were

laughing and seemed to think the war over as far as their fighting was

concerned. They handed our boys their watches, knives, money, cigarets, etc., as

they filled up to be searched. A daschund dog came with them answering the name

of ‘kaiser’ and followed the ‘squareheads’ back to the prison camp. Here is

where we got the name of ‘not knowing when to stop.’

INTO THEIR OWN BARRAGE

“In the excitement of taking prisoners we had charged

forward too fast and were ahead of our own barrage, in other words ‘between two

fires.’ Quite a few of our own men were badly mangled here. Not being with my

own company, I didn’t know any of the wounded, and it was hard to leave them,

but for our own safety we were ordered to the right into some trenches. The

doctors, first-aid men, and Red Cross, followed right up and took care of the

wounded. Rocket signals were sent up and our airplanes which were flying

overhead, hurried back to the artillery and soon the shells were tearing great

holes in the earth ahead of us again. I was now with Co. A, Three Hundred and

Nineteenth infantry.

“As we advance again we came to a swap where the

engineers were putting up a pontoon bridge. After crossing this we ran into a

machine gun fire from a woods. Locating a machine gun and attempting to flank

it, I found myself with Co. G of the Three Hundred and Nineteenth (Karl Hewitt’s

company.) I connected myself to the company and was assigned to Corp. Shafer’s

automatic squad. We soon captured the machine gun and advanced into the woods,

and to dugouts where we spent the early part of the night. On our left 25 or 30

Germans started toward us across an open field with their hands up. Some of the

foreigners in the company opened fire on them and they fell back and gave us an

awful battle. Later in the evening the German artillery got our rand and

airplanes dropped bombs on us. Al told we spent a very uncomfortable night to

say the least. (Corp. Shafer is a Wilkinsburg boy, and worked at Hall’s

roundhouse on the Union railroad.)

“Soldiers killed or dying from being hit by shrapnel

turned a horrible yellow color, but those hit by machine gun bullets turned

blue.

“On this afternoon when Jerry was making things warm

for us our artillerymen sent over some liquid fire shells which set fire to the

woods which the Huns were holding, and with the officer’s field glasses, we were

able to see them retreating over the hills.

“On Sept. 27, at 4 a.m. (before daylight) we combed the

woods which seemed to be a lumber camp or source of wood supply for the German

army. Without a barrage we conducted a raid on a little town which the Germans

had used as a hospital, and which as they retreated they left burning. Passing

through the town we went up a hill through another woods, then down the other

side of the hill to the edge of the woods overlooking the Meuse river. The city

of Dunn sur Meuse could be seen in the distance. In the last woods we met

several machine guns and captured them. We had reached our objective at about 10

a.m. but the Three Hundred and Twentieth infantry on our left had med with stiff

resistance and had not advanced as far as we were.

IN THE ENEMY’S QUARTERS

“We dug bivrys [sic] big enough to shelter us from

machine gun fire and Company headquarters were established in what had been a

German officer’s quarters. Her there was glass in the windows, lace curtains, a

desk, a table, a big leather Morris chair, and a ‘regular’ bed in another room.

The rooms were wired for electric lights. While here we were shelled quite a

little. They used gas on us in the woods. This little bungalow occupied by

Company headquarters had also been a first aid station. We spent the night here,

another company relieving us in the morning and at 6 a.m. we moved back to

support trenches on top of the hill.

“On Sept. 28, the Three Hundred and Twentieth on our

left, had still not reached their objective and we were in a pocket and being

shelled from three sides, getting quite a lot of gas. German airplanes fired on

us with machine guns but our planes drove them off. Towards night to make

matters wore [sic] it started to rain and rained all night. We were in a shallow

trench and had to stay down on account of the flying shrapnel and machine gun

bullets. The trench was soon a creek and we were soaked. German planes flew over

us again, not a hundred feet above, firing their machine guns directly at us.

“On Sunday morning, Sept. 29, about 5 o’clock we were

relieved and started on our march back. Having no water in my canteen, it was on

this march that I got so thirsty and drank from a shell-hole. I had given nearly

all of the water in my canteen to wounded men. It was very risky business to

drink water out of a shell-hole, as the rain might have filled the hole made by

a gas shell which poisons the water.

“On our way back we saw great quantities of ammunition

and rifles and even heavy artillery that had been captured from the enemy. Some

of this artillery had already been turned around and our gunners were firing

German ammunition from German guns. Our wounded had been taken care of and the

dead were being buried. In some places there were great heaps of dead Germans. A

great number of horses were dead along the roadside, most of them having been

gasses – some of them even had gas masks on, probably put on too late. The boys

called these horses and mules ‘more bully beef.’ We passed several German

airplanes that had been brought down and saw lots of terribly mangled soldiers

when we passed a field hospital. Further back we met some of the little French

whippet tanks, going like the dickens to the front. They were probably making 15

miles per hour and are about the size of a Woods Mobilette with two men in each.

We also me auto trucks of ammunition and rations, and artillery was being

brought up closer to the front.

“About noon we stopped in a woods and the kitchen

wagons came up, but before we could get started to eat ‘Jerry’ commences

shelling the woods. About the same time we received word (by airplane, I

believe) that the Seventy-ninth division in front of where we were, was being

driven back. There certainly were a lot of wounded soldiers being brought back.

Without waiting for dinner and as tire as we were we turned around and started

forward to help our comrades. We had progressed only a short distance when

another plane flew over us and dropped a message telling us the Seventy-ninth

division had overcome the resistance and was again advancing. Then we had our

dinner by the roadside, the first warm meal for four days.

“We marched by reserve trenches at Cuisy, where Corp.

Shafer, Private Books and myself dug a bivry and tried to sleep. We had just

finished our little dugout when it commenced to rain. All night long the army

mule rent the air with his unearthly braying. (The warm dinner consisted of

stew, tomatoes, coffee, bread, jam and sugar.)

“On Sept. 30 we were moved to another part of the

trench and made a new bivry and a fire. For dinner we warmed up some canned

roast beef and bacon and made coffee. In the afternoon I cleaned up my equipment

and rifle and at 6 p.m. supper was served from the kitchen, which was now

located in the trench. We had roast beef, beans coffee, doughnuts, bread, syrup

and sugar.

“Oct. 1 – At 2 p.m. the men who had been lost came back

to the company. Breakfast at 8 a.m., consisting of bread, bacon and coffee. In

the forenoon I cleaned up for inspection, also washed my feet and we had foot

inspection. For dinner at 2 p.m. we had fresh beef stew, bread, jam, coffee and

sugar. In the afternoon the first mail came since Sept. 22, via ‘G’ company.

After supper at 6 p.m. Shafer and I had a long talk about Wilkinsburg.

“Oct. 2 – I was on gas guard from 1 to 2:30 a.m. The

Germans were throwing shells over our heads at artillery trenches on the hill

behind us. Breakfast. Was placed again on gas guard from 8:30 to 10 a.m. We

could see and hear the great shells going over our heads and see them tearing

great holes on the other hill. Dinner was good. Steak, gravy, potatoes, bread,

Karo, coffee. About 3 p.m. I located my own outfit (Co. F, Three Hundred and

Twentieth infantry) in the same reserve trenches about two kilos to the right.

The boys made quite a fuss over me and seemed glad to see me again. Corp. Cast

and Corp. Scheidor in particular seemed glad that I hadn’t been wounded or taken

prisoner.

“I did not know until now that Kirk Earls had been

killed and Lewis Gray wounded. I received three letters from him, two from

brother Earl, nine from Florence, one from Cousin Pearl, one from Frank Gibson

and one from Johnny Weyer, also two ‘Sentinels.’ This mail we were told was

delivered by airplane. One of the letters from Florence had also made the trip

from Washington to New York via airplane. I returned to’G’company for my

equipment and Capt. Smith gave me a very nice note to my own captain which I was

permitted to keep. About 6 p.m. Joseph Herdman of ‘D’ company came to see me and

told me Corp. Townsend of ‘C’ company had been wounded. Bienna and I made a

bivry together. My roll had been opened and I lost many of my personal

belongings. (I was wearing my heavy sweater, but a light one and my camera were

among the missing articles.)

SAW AIRPLANE BATTLE

“October 3 – Finished reading my letters this morning

after breakfast. Cleaned my equipment for inspection in the afternoon. Had a

long talk with Worley Gilham in the afternoon and saw some American planes

engage a German aviator. The German machine was brought crashing to the earth

not far from where we were located. After supper I visited the Three Hundred and

Thirteenth Machine Gun battalion and learned that Coyle Carothers of Wilkinsburg

had undergone a successful operation for appendicitis at base hospital No. 38 at

Chatalon, but would not be back to his outfit. The artillery’s captive elephant

balloon (observation) had to be taken down several times this afternoon on

account of German airplane attacks.

“Jerry sent over a good bit of gas at night and we had

to put on our gas masks no less than a half dozen times. Some of us went to

sleep with them on.

“We got up at 5:45 a.m. on October 4th and rolled our

packs. This was done so that we could always be ready for the emergency. Corp.

Martin came back from gas school today and joined the company. A jack rabbit

running across the hill attempted to jump over our trench and fill into Corp.

Timmor’s arms and he had rabbit for dinner. During the afternoon three Boche

planes were brought down by American aviators within a very few minutes. It was

rumored that the Three Hundred and Eighteenth had reached their objective and

the Three Hundred and Nineteenth had gone forward to help the Three Hundred and

Seventeenth. After supper we unrolled our packs and tried to sleep. We were

gassed all night but had no casualties.

“On Oct. 5th, after breakfast we rolled our packs, then

cleaned up for inspection and wrote letters. After dinner we signed the pay

roll. First Sergt. Thompson was sent to the Officer’s Training School for good

work done in the line. German planes again attacked the elephant balloon a

number of times, the operator dropping in a parachute each time, and the balloon

being pulled down in time to save it. Unrolled our packs and slept in the

trenches again.

PLANES ATTACK BALLOON

“Oct. 6 – Up at 5:30 a.m. In the forenoon I took a walk

over the battlefields at Cuisy. In the afternoon German planes made four attacks

on the artillery observation balloon, the operator getting away safely each

time. Finally a Jerry plane dropped from a great height, firing white hot

bullets which set fire to the balloon and in come down in smoke. The operator

landed safely with his parachute. All the machine guns, automatic rifles and

anti-aircraft guns fired at the enemy plane but it got away. Slept in the

trenches again tonight. Back of our trenches the heavy artillery was throwing

shells into the enemy lines a distance of about 15 kilometers. Corp. Caster was

made sergeant for his exceptionally good work in the line.

“Oct 7. – Was treated to butter this morning at

breakfast. I worked in the kitchen all morning carrying water, shining pans,

etc. – regular kitchen police work. At 3 p.m. we rolled our packs and after a

light supper at 7 p.m. marched two miles to our left in a heavy rain to trenches

back of Montfaucon. Here our coast artillery reserve guns were throwing

eight-inch shells 22 kilometers into Anereville at the rate of 30 a minute,

every other one being gas. It rained all night, and on the hike I tripped over

barbed wire a number of times and fell into shell holes. Cope slipped and broke

his leg on this hike, I was on gas guard two turns of one hour each in these

trenches.

“On Oct. 8, we again rolled our packs and marched to

our left to some other trenches. This march was not long and we reached our

destination before noon. While cleaning my equipment in the afternoon rumors

came in, supposedly by wireless, that peace had been signed by Turkey, and

Germany was asking for an armistice. The dispatch was received by the artillery.

The Three Hundred and Eighth engineers of Ohio, formerly trained at Camp

Sherman, were working on a road nearby. Airplanes flew low and dropped copies of

newspapers.

RUMORS OF ARMISTICE

“On our left we could see the ruins of a castle on top

of a high hill where it is reported the kaiser watched the slaughter of his

legions before Verdun in the first Verdun offensive, through a million dollar

telescope. The telescope could not be removed in time and was destroyed. The

high hill was near Montfaucon. Went to bed shortly after supper.

“On Oct. 9, we were up at 6 a.m., rolled our packs but

did not move out until 5 p.m. There were rumors that officers were betting five

thousand francs (one thousand dollars) that no guns would be fired after the

following Monday, October 14. As we moved forward from the reserve trenches to

the support trenches, Dan Strang of Wilkinsburg walked along beside of me for

quite a distance through the woods before we said good-bye and he returned to

his company. We stopped near the top of a hill and dug in. Later we left again

and went to trenches near Nantalois, about five kilos from Cuisy. On this march

we met a long string of German prisoners being taken back. As they passed we

heard on German say in pretty good English: ‘The American soldier is not very

big, but he knows how to handle the bayonet.’ They may have met some of the

little Italian boys of our division, who certainly were adept in the use of the

bayonet.

“One prisoner had been shot in the knee. He told us

that he and four other Germans had started over to give themselves up. The

others got scared and started back and were killed, but he came on and was

wounded. He said they hadn’t eaten for 10 days. Someone gave him half a loaf of

bread and he devoured it quickly, in a manner supporting his statement. He told

us there were not many Germans ahead of us and that they had no soldiers in

support or reserve and practically no ammunition. He also told us the people

back home (in Germany) were starving and he was glad to be in the hands of the

Americans. He was well advised for he knew that nearly three million Americans

had reached France, that Turkey was suing for a separate peace, and that Austria

was liable to break with Germany at any minute. After a rest until 2 a.m. we

carried rations up to the men in the front line.

“Oct 10. – At 11 a.m. we were ordered from the support

trenches with full packs to follow up the advancing front line. On the way up we

unstrapped our blanket rolls from our haversacks and left them by the roadside.

A Jerry plane or observation balloon must have seen us, for soon after we

started again the Huns shelled the road and blew our rolls to pieces. I lost

everything I had except my razor, shaving brush, soap and towel, which I was

carrying in my haversack on my back. Corp. Kellerman, Bax and I found a trench,

removed a dead soldier from it, and dug a bivry which we covered with a piece of

tin we had torn from a destroyed German billet. The sheet-iron probably saved us

from some painful scratches for shrapnel was continually raining on it all night

and set up a merry patter. All night we took turns on gas guard.

“Moving up to these trenches it was not an uncommon

thing to stumble over a shoe with a foot in it, or a glove with a hand in it,

and at one place I saw a helmet with brains in it.

“OVER THE TOP” AGAIN

“Oct 11. – Up at 6 a.m. and at 8 a.m. we marched about

one kilo to other trenches at the front and went over the top at 2:30 p.m. into

the woods. Here Capt. Maag was wounded on the chin by a rifle grenade, Corp.

Herrig was killed and Corp. Kellerman was wounded by machine gun bullets. Joseph

Herdman was gassed here. About dark Vogel, Semanchuch and I were ordered back

into the woods by Corp. Schedemantel. We were met by Three Hundred and Fifteenth

Machine Gun men who told us our division had been relieved and we went back with

them to battalion headquarters, then to the bivry Bax and I made the day before,

where we ate our canned salmon, beans and crackers and took turns on gas guard

all night. About 3 a.m. Jerry sent over quite a bit of gas with his high

explosive shells. I was very tired and slept with my gas mask on. Gas shells

burst with a puff instead of a band, throwing liquid which turns into gas when

it evaporates. The Germans have a habit of sending gas over early in the morning

along with high explosive shells. The liquid scattered by gas shells of the

particular variety over bushes and grass doesn’t evaporated until the sun comes

up, and one may be unsuspecting of gas until it is too late.

Wm. M. Scheider, Bellevue, Co. I, 111th

“Anybody lying on the grass or passing through bushes

were the mustard liquid gas has been scattered usually gets terrible burns.

German machine gunners have been wearing bands on their arms with a red cross on

them. They are sometimes mistaken for our own first aid men. In these woods we

found some trees which had two and three platforms built between the limbs upon

which machine guns were operated, also a large box buried in the ground under

bushes at the foot of a tree, where another machine gun had been placed. Worley

Gilliam was gassed today.

“Having been relieved by the Sixtieth and Sixty-first

infantries on Oct. 12, we moved back to support trenches near Nantalois where we

washed up, shaved and slept in the morning. While eating supper about 4 p.m. the

Huns shelled the area, one shell knocking a horse from under a military

policeman and blowing it all to pieces. An American soldier was bringing back

six German prisoners when a shell killed all the prisoners but only shook the

guard up a bit. Stretcher bearers were bringing back quite a few wounded men,

and many prisoners were being marched to the rear. At 5 p.m. we started on an 18

kilo hike over very rough roads to a woods near Avocourt, where the whole

battalion was resting. We arrived here at 11:45 p.m. and as I had no

shelter-half and no blanket, I slept with Semanchuch. We used our slickers for a

mattress and threw his blanket over us.

IN THE REST AREA

“Oct. 13. – Bread, coffee and bacon for breakfast at 8

a.m. Then Martin and I walked five kilos for water and missed our dinner. We had

a band concert in the afternoon. Also got two blankets and new clothes. The

Y.M.C.A. issued each man one and one-half cakes and two square inches of

chocolate. After supper I visited with ‘C’ company. Learned that Hanley had been

killed, also about Herdman’s wound. Artillerymen here tell of finding a German

chained to his cannon, but who when released turned his gun around and made a

direct hit on a German ammunition dump 10 kilos back.

“Oct. 14 – Got up at 4 a.m. today, breakfast at 5 a.m.

and then hiked four kilos to Brizeaux. We were taken past the town about one

kilo and had to walk back. Here we billeted in barns and old buildings. I was

located in an old barn No. 26 and was under Corp. Sheidmantel. I soon found the

remains of a cot which I repaired and had quite a comfortable bed. Here we were

able to buy milk and Dutch cheese sandwiches. The kitchen did not arrive until

the next day, and so we ate the iron rations we were carrying with us.

“Oct. 15. – No reveille today. We got up and got our

own breakfast at 7 a.m. We were issued more new clothes in the morning and in

the afternoon we had a hot shower. Our underclothes being full of ‘cooties’ had

to be thrown away and I had none for a few days. Kitchen came in the afternoon.

It rained all evening. Three sick soldiers who hadn’t been able to keep up with

their outfit stayed with us for supper and slept in our billet.”

Lt. Z. E. Wainwright, Machine Gun Co., 111th

Sgt. Russell Rollins, 111th

Sgt. Thomas L. Dove, 111th

|