| |

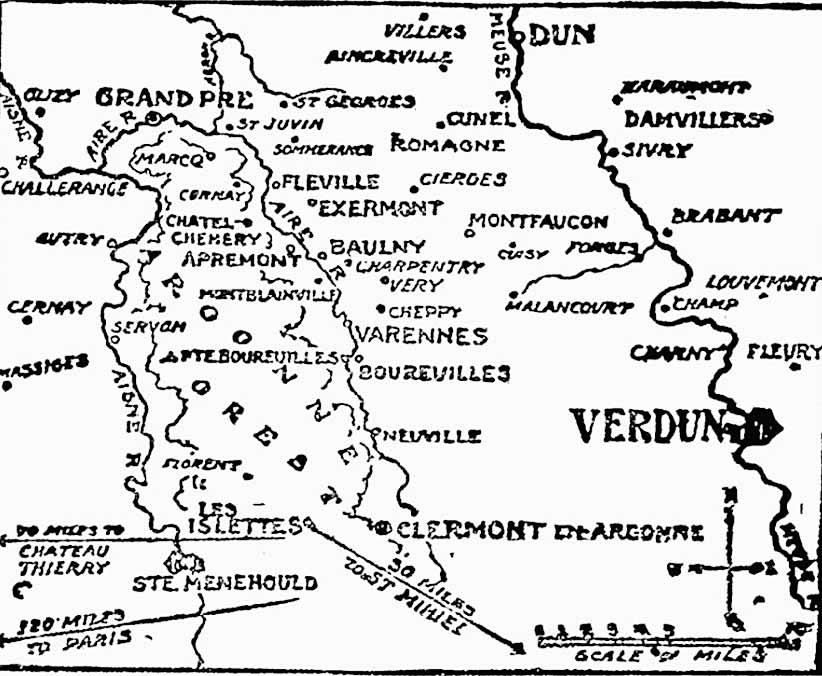

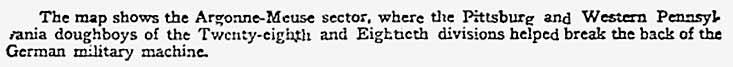

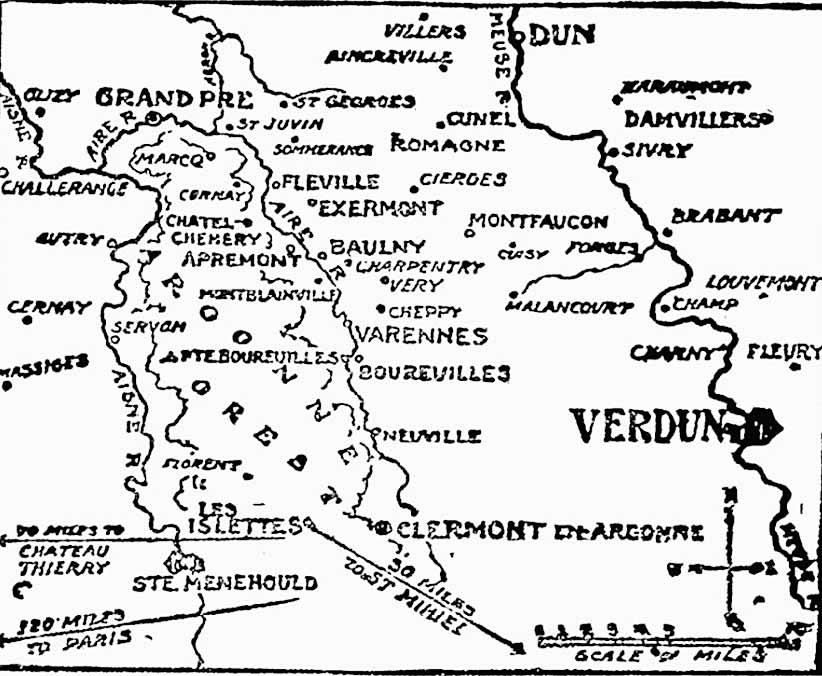

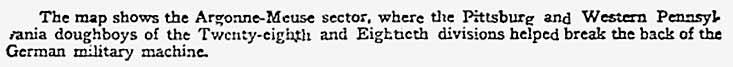

A History of Pittsburg and Western Pennsylvania Troops in the War

By John V. Hanlon (Copyright 1919 by The Pittsburg Press)

Chapter XV

(The Pittsburg Press, Sunday, April 13, 1919, pages 78-79)

Names in this chapter: Allan, Jarrett, Heimann, McHenry, Austen, Davis,

Jeffery, Lynch, McLain, Mackey, Miner, Summerton, Dickson, White, Hay, Muir,

Smathers, Henderson, Shannon, Weigle, Rickards, Bubb, Cronkhite, Sturgis, Brett

The Old Eighteenth of Pittsburg, now the One Hundred and Eleventh Infantry of

the Twenty-eighth Division, participated in some of the bloodiest battles in

France and did much towards tolling the knell of the parting days of Germany’s

ambitions for the world conquest and Dominion. The Eighteenth was one of the

strongest links in the invincible “Iron Division.”

IN THE MEUSE-ARGONNNE OFFENSIVE THE PENNSYLVANIA DOUGHBOYS HAD SOME HARD NUTS TO

CRACK AND THE TAKING OF APREMONT PROVED TO BE ONE OF THE ESPECIALLY SEVERE

INSTANCES OF BITTER FIGHTING. THE TOWN WAS AN IMPORTANT STRONGHOLD FOR THE ENEMY

AND WAS HELD IN FORCE MUCH THE SAME AS FISMES AND FISMETTE. THE TWENTY-EIGHTH

DIVISION SUFFERED HEAVILY THERE AND OFFICERS WHO PARTICIPATED IN THE BATTLE HAVE

TESTIFIED THAT THE GUTTERS IN THE STREETS OF THE TOWN RAN RED WITH BLOOD. FOR

FOURTEEN DAYS THE TWENTY-EIGHTH POUNDED UP THROUGH THE ARGONNE AND WAS JUST

PREPARING TO ASSAULT GRANT PRE WHEN RELIEVED AND SENT BACK TO REST BILLETS AND

LATER TO JOIN THE NEW AMERICAN ARMY THEN PREPARING FOR A DRIVE ON THE GREAT

FORTRESS OF METZ. THE ARTILLERY DIVISION WAS DETACHED AND SENT INTO BELGIUM TO

ASSIST IN HARRASSING THE THEN FLEEING GERMANS.

In taking the Apremont, the “Iron Division” had the

attack all planned, and the men were ready and eager to strike, when the Huns

broke things up in general with a bungling attack of their own. The assault on

Apremont has been recorded as one of the bloodiest in the history of the war.

The Boche was not only the one to suffer, for the “Iron Division” lost hundreds

of men, while thousands were wounded. Officers who participated in the battle

have, under solemn oath, testified that the gutters in the streets of Apremont

actually ran red with blood.

The enemy had brought up strong reinforcements of

comparatively fresh troops, and had apparently decided to make a stand. The

importance of Apremont was great to them for it was on the Brunhilde line and

constituted the first defense. On it, to a considerable extent, hinged the

success or defeat and rout of the German armies to the north. The town was held

in force, much as were Fismes and Fismette, and presented the same problem to

the Pennsylvania commanders. Every approach to the town was held by a

concentration of forces manning machine guns, while snipers were in every

vantage post possible. Previously the Germans had left one man in charge of a

machine gun nest, but now they were manned by small garrisons. The bombardment

of the town was terrific, and hand-to-hand fighting raged for many hours which

finally stretched into days, before the town was actually occupied by the

Pennsylvanians. It was the last big battle that they participated in before the

signing of the armistice, although they continued the advance and fought a

number of successive minor engagements later.

Not until compelled to do so, did the Germans

relinquish their hold on Apremont, and when they finally did fall back, it was

only to gather strength again, reinforce themselves with fresh troops and launch

counter attack after counter attack. None of them were of any avail for the

Keystone boys, once inside the town, could not be shaken, and their heroism has

never been equaled.

GERMANS ATTACK FIRST

A few hours before the Americans were to make their

attack the Germans broke loose with their attack. This was a surprise to the

Pennsylvanians, and the result of it was more than the Keystone men had planned

to receive in their own attack. Although reinforced strongly by machine gunners,

the slaughter of Germans was terrible. The first wave ran right past our own

machine guns into the hands of the infantry, and when those who survived saw the

plight of their advancing comrades, but too late to escape, they made a

half-hearted attempt to return to their own lines. In so doing they again ran

past our machine gunners who were secreted in shell craters and they were mowed

down almost en masse. The few who survived were lucky. The American losses were

not heavy. It was a blundering attack, and nothing was gained by it. It was

planned to have a demoralizing effect upon the advancing allies, but instead,

like some of the previous German attempts to break up the offensive, had a

heartening effect.

The attack caused some little confusion in the American

lines, and the assault that had been planned for 5:30 that morning had to be

re-organized, but it went on just the same and the Yanks entered the village of

Apremont, just as they had intended.

GERMANS LAUNCH ANOTHER ATTACK

After the Americans had entered the village the

Germans, after extensive preparations, launched one great attack, by which they

evidently had proposed to unseat the holders of the village and drive them back

beyond its limits and the surrounding positions. They came on confidently and

with undeniable courage like gallant veterans, never flinching nor giving an

inch, the Pennsylvanians stood up to them, while wave after wave swept forward,

and was mowed down in pitiable slaughter. The fighting was desperate. In many

instances it resulted in hand-to-hand grapples, as dogged and determined as the

primitive struggles of man in the dark ages, and brutality reigned supreme. It

was not for our men to fight this way, and they didn’t like it, but orders were

orders – and hold they would regardless of life or the methods that had to be

resorted to in order to keep back the tides of enemy infantrymen that threatened

to overwhelm them and sweep onward. There was no time nor inclination either, to

take prisoners or surrender, and the only one eventuality under such

circumstances was resorted to. They killed as swiftly and as mercifully as was

possible. There were a few places where the Germans gained slight advantage.

Many instances of personal and individual bravery worthy of note, took place

during the desperate fighting that raged around Apremont and in its streets.

ORGANIZED FRESH ATTACK

It was at this time that Corp. Robert E. Jeffery of

Sagamore, Pa., and Sergt. Andrew B. Lynch of Philadelphia distinguished

themselves. As members of headquarters company of the One Hundred and Tenth

infantry, they were in charge of a one-pounder trench mortar battery, located at

a position slightly north of the village. Receiving orders to move their

position to the rear, they did so, and shortly afterward learned that their

commanding officer, Lieut. Myer S. Jacobs had been taken prisoner. Immediately

the two men organized a rescue party consisting of a total number of five and

moved forward, attacking a machine gun nest manned by 36 Germans, who it was

known, had Lieut. Jacobs in their custody. The little party killed 15 of the

Germans, took three prisoners and released the lieutenant uninjured.

Immediately after his return to the American frontlines

Sergt. Lynch took 75 fresh men, and with revolvers drawn, led them against the

enemy in a fresh attack, in which they penetrated the German line to a depth of

two-thirds of a mile and established a new position in a ravine north of

Apremont. Sergt. Lynch was officially cited for bravery.

PENNSYLVANIAN CITED FOR BRAVERY

Although he had formerly distinguished himself at the

Marne, Capt. Charles L. McLain, of Indiana, Pa., again gained prominence in the

Apremont fight. While engaged in fighting with his own company, he was informed

that Co. C of the One Hundred and Tenth infantry was unofficered [sic]. His own

company was part of the reserves and he had a number of junior officers under

him. Without a moment’s hesitancy, Capt. McLain turned the company over to one

of these and went to the aid of Co. C. He personally led the first wave that

this company made in a hot attack and was wounded himself. But his wound did not

stop him. He went right along with his men hobbling with a cane until the

objective was reached. Then he permitted them to send him to a hospital. He

later recovered from his wounds and rejoined his company.

The One Hundred and Ninth infantry bore the brunt of

the second German assault on the American lines while they were in Apremont.

Maj. Mackey, who, as Capt. Mackey distinguished himself at the Marne, had

established his headquarters in the basement of an old building, the top of

which had been destroyed by shell fire. With him were the battalion adjutant and

a chaplain, members of his staff. When telephonic communication was severed from

his headquarters and runners which had been giving him information from

different points along the battle line ceased to come, he instantly knew that

the Germans had gained some ground and were advancing. This would mean he would

be captured unless the post was removed further to the rear of the fighting

troops. While meditating, he and his men suddenly heard the cracking of a

machine gun, which had been set up on the floor over their heads. It blazed away

merrily for a time, with its regular “rat-a-tat, rat-a-tat” which sounds for all

the world like a pneumatic riveter at work sealing together heavy cordons of

steel. Simultaneously he heard the bawling of commands in a hoarse German voice.

This was sufficient to make the major aware that the machine gun above their

subterranean post was manned by a crew of Germans.

Officers of the One Hundred and Ninth infantry, as well

as men, saw what was taking place. The sight of the machine gun over the post

command, aroused their anger to a greater pitch and with a wild howl and grim

determination, they made for it. It didn’t take long to mop ‘em up, and in a

short time the Germans were on the retreat again in that particular section, and

fighting to the northward.

INFANTRY ADVANCES BEYOND APREMONT

With the German assaults successfully stemmed, the

American division forged ahead once more and advanced beyond Apremont. The

fighting was sever however and the advance was made over ground that was

contested every rod. Directly in the way of the advance was Pleinchamp farm,

which was cleared up only after considerable effort and some very brisk

fighting. The farm was a group of small buildings, as is usually the case when

the term “farm” is used in France, and was so arranged that a body of men making

an attack on one of the buildings would be subject to the whole fire of the

Boches from the others. The buildings afforded excellent places for the

secretion of machine guns, automatic rifles, one pound mortars and snipers. The

walls of the structures were usually of stone, very thick, and an excellent

protection from invasion. The Germans were finally cleared out of Pleinchamp

farm, and the objective, Chatel-Chehery, now lay straight ahead.

Undaunted, the heroes kept right on going. There were a

number of cases where companies emerged from combat under the command of a

corporal, or some other non-commissioned officer, because all of the

commissioned men had either been killed or wounded so badly that they could not

direct the fight. The Apremont fight was a costly one but through it name of the

Keystone division has been written in the records of time. From Apremont, the

course of battle veered slightly to the west although it still followed the

course of the river. They artillery now came into the Apremont and there ran

into severe shelling, the same circumstances that was met when it entered

Varennes. One battery of the One Hundred and Ninth artillery was almost

completely knocked to pieces by the heavy shells. Guns were torn from their

carriages, caissons destroyed and men injured. Col. Asher Miner of Wilkesbarre,

Pa., seeing the plight of the battery went out in person and supervised the work

of reorganization of the battery and its reconstruction. For his personal care,

and the attitude show he was commended very highly by Brigadier General Price –

in the following words:

“Col. Miner has shown bravery on many occasions, but it

is when men do what they do not have to do that they are lifted to the special

class of heroes. Miner is one of these.”

Col. Miner was constantly looking after his men, and

their equipment, and his general efficiency and ability are not questioned. It

was shortly after the above quoted commendation that he was injured so severely

that his foot had to be amputated. A piece of shell struck him in the ankle.

KREMHILDE LINE NEXT

The One Hundred and Twelfth infantry took Hills 223 and

224, which lay directly in the path of Chatel-Chehery. These two hills presented

formidable obstacles and were of considerable military value to the enemy. They

were strongly garrisoned, but despite this fact the Americans never hesitated.

Because of their vantage point at the top of the hills the Germans were only

able to postpone the advance for it took four days to capture both hills, in

conjunction with Chene Tondu Ridge.

The Americans were careful, for it was a situation in

which much might be lost and where much might be gained. The methods employed

were of the nature of a siege. The Pennsylvanians were familiar with this method

of fighting. While some of the forces spotted the German firing positions and

turned their guns upon them, keeping up a steady and non-intermittent fire,

others crept forward to selected posts. These in turn set up a peppery fusilade

[sic], while others would advance up the side of the hills in the same manner.

For four days this kept up, and finally when the doughboys were near enough to

the tops they dashed over. For their faithful work that night, they were

permitted to remain on the crest and sleep until morning. More of France’s

territory was redeemed.

WARREN BOY IS HERO

On the night before the capture of Hills 223 and 224,

afflicted with Spanish influenza and suffering from a number of wounds in his

shoulder and legs, Sergt. Ralph N. Summerton of Warren, Pa., sat in the kitchen

of his company, feeling mighty miserably. The wounds were the result of a German

“potato masher” as the German trench bomb is familiarly known, which went off

close to him. Sergt. Summerton, despite his wounds, refused to go back to the

hospital, but had been treated at a field hospital. He had a couple of metal

tags with him to show for this. Hence he was not made to go to the rear

hospital.

While nursing his troubles, Lieut. Dickson, battalion

adjutant, and Benjamin F. White, Jr., a surgeon, entered the kitchen, and Sergt.

Summerton asked how the regiment was getting along, He was informed there was no

one to lead Co. I into the attack. Summerton immediately applied for the job.

He was admonished to rest up by the surgeon, but

Summerton refused to listed and started for the company, assumed its command,

and was a the head of the first troops to go against. Hill 24. He actually was

the first person of the attacking forces to reach the top of the hill. The

brigade commander saw him do the deed and realized his courage, knowing that he

was almost reeling from his illness and his wounds. Even after the soldiers

reached the top he continued to lead the attack until a bullet in the shoulder

forced him to retire.

CHATEL-CHEHERY FALLS

With the principal defense out of the way, the “Iron

Division” steadily marched up the valley of the river on Chatel –Chehery. In the

course of progress the men captured a German railroad that had been a part of

their communication system, with 268 cars and seven locomotives. The locomotives

and cars were camouflages cleverly to blend with the trees, ferns and bushes of

the forest. The locomotives were of a peculiar design, having a large boiler,

small drive wheels, and a large fly wheel located centrally on top of the

broiler. Four of them had been partially destroyed before capture, but the One

Hundred and Third engineers soon had them in order and they were running full

tilt and performing valuable service.

Two other valuable captures were made by the “Iron

Division” at the time of the fall of Chatel-Chehery. One of these was a saw mill

and 1,000,000 feet of sawed lumber. The saw mill was an electrically operated

one and with it were several electric stations all of which were immediately

repaired and set to work for the conquering division. The other capture was

perhaps of greater benefit. It was a complete field hospital, consisting of 15

cottages, built in an attractive spot on the side of a hill. The buildings were

all connected with picturesque walks made of brick and red painted concrete. A

large building in the center, used as the operating headquarters was modernly

constructed and equipped completely with a modern operating room. A ghastly

sight greeted some of the doughboys of the Twenty-eighth, when they entered this

room. So hasty had been the German retreat that a patient upon whom they had

been working was left on the operating table. He had one leg cut off, and was

dead. Instruments being used in the operation were laying on the table, and it

was evident that the patient had been left to die, at the moment of operating.

Chatel-Chehery proved easier than had been

anticipated. There was severe fighting which could end only in one way – the way

the Pennsylvanians intended it to end. They entered the town on the same day of

the opening attack.

STOPPED AT GRAND PRE

Freville lay in the path of the fighting division, and

it was captured. The outskirts of Grand Pre, a formidable German stronghold, lay

just ahead. The American division under its able commanders immediately

commenced to surround the city and capture it, where official orders were

received, checking them in their preparations and returning the entire division

back into billets for rest, as it was stated 14 days of continuous fighting was

enough for any division. Another division took its place before Grand Pre, and

in one of the severest fights of the way, succeeded in capturing it just before

the armistice was signed.

In the meantime the “Iron Division” was moved southward

across the Aire, and finally came to rest in positions at Thiacourt, about four

miles back of the front lines and 16 miles from the German fortress of Metz.

Following the capture of the St. Mihiel salient by the Americans and French, a

general assault on Metz was being planned, but again the armistice save a bloody

combat for the assault did not materialize. The allied armies were ready

however, and in all probability would have captured this fortress that hundreds

of military men have pronounced invulnerable.

ARTILLERY ON DETACHED SERVICE

While the units of the Keystone army were resting at

Thiacourt, the artillery was detached and sent to harass the fleeing Hun on the

roaring, blazing battle line in the north. The German arms were now rapidly

nearing a complete collapse, and the part the Pennsylvanians played in the

achievement is one to be proud of. Traveling to the northward for many miles,

the artillery finally found itself in Belgium, that shell torn, scarred, black

waste, over which armies had fought for four years. Here they were attached to

the army of pursuit, which was intended to hound the fleeing Huns to the last

stand. The artillery of the “Iron Division” however did not see action, for the

armistice interrupted. To see the devastation, black ruin and bleak barreness

[sic] of Belgium incensed the gunners with an increased abomination of the Hun,

and they are sorry they did not get to do the work that had been mapped out for

them.

Unexpectedly orders were received while the Fifty-sixth

brigade was at rest near Thiacourt, two days after the arrival of the division

at that rest camp, ordering them into the line extending from Haumont, Xammes,

to Jaulny, evidently in preparation for an assault on Metz. This was shortly

after the middle of October, and the men were looking forward to some more

severe fighting. They had now become a part of the Second American Army. The

Fifty-fifth brigade was to have been relieved in 10 days, but this order was

countermanded, and the brigade moved up in line with the Fifty-sixth instead. A

number of sharp engagements were fought, which however, lost their importance

and received very little publicity due to the rapid collapse of the German arms,

which was not inevitable. Therefore it was apparently in these positions that

the armistice stopped the Pennsylvanians. Six months overseas fighting, during

which an enviable reputation was made, won for the Keystone men, the right to

wear the gold chevron on the right sleeve. After the signing of the armistice

the whole division was moved back to a position near Heudicourt, where it

enjoyed a fine rest with very little hard work attached to it. Daily drilling

took the place of fighting. The men were kept in good condition by this process

ready for any emergency. Finally when the Army of Occupation was well up to its

positions on the Rhine, the Twenty-eighth was chosen as one of several divisions

to make up a line of support to the troops entering Germany and were assigned a

base in Lorraine. By being assigned as part of the army of support, the division

was given a direct share in the final triumph, and the honor came as recognition

of the excellent service and sacrifice it had made during the last months of the

great World War.

Maj. Gen. William H. Hay succeeded Gen. Muir in command

of the division after the armistice was signed, and Gen. Muir was given the

command of the Fourth Army corps. He left the Twenty-eighth with deep regret.

Before leaving he took occasion to once more commend the division in its

entirety for its part in the war, and directed that special orders commending

each unit, and mentioning some of the special feats it accomplished, be drafted

and distributed to every man in the division. This was done. The communication

in part read:

“The Division Commander desires to express his

appreciation to all the officers and soldiers of the Twenty-eighth division and

to its attached units who at all times during the advance in the Valley of the

Aire and in the Argonne forest, in spite of their many hardships and constant

personal danger, gave their best efforts to further the success of the division.

“As a result of this operation, which extended from

5:30 o’clock on the morning of Sept. 26 until the night of Oct.8, with almost

continuous fighting, the enemy was forced back more than 10 kilometers.

“In spite of the most stubborn and at times desperate

resistance, the enemy was driven out of Grand Boureuilles, Petite Bouruilles,

Varennes, Montblainville, Apremont, Pleinchamp Farm, Le Forge and Chatel-Chehery,

and the strongholds on Hills 223 and 224 and La Chene Tondu were captured in the

face of strong machine gun and artillery fire.

“As a new division on the Vesle river, north of

Chateau-Thierry, the Twenty-eighth was cited in orders from General Headquarters

for its excellent service, and the splendid work it has just complete assures it

a place in the very front ranks of fighting American divisions.

“With such a position to maintain, it is expected that

every man will devote his best efforts to the work at hand to hasten that final

victory which is now so near.”

Although the One Hundred and Ninth, One Hundred and Tenth, and One Hundred and

Eleventh infantries, distinguished themselves throughout the Argonne-Meuse

campaign, the One Hundred and Twelfth displayed no less valor, and took its

share of the severe fighting with equanimity of feeling, fulfilling each task

with a thoroughness that only true Pennsylvanians can accomplish. Maj. C. Blaine

Smathers of the University of Pittsburg, who resides in Oakmont, during a

portion of the offensive was second in command of the regiment and later became

its commander when officers ahead of him received promotions. Maj. Smathers was

gassed and was forced to undergo treatment at a hospital. Maj. Smathers tells

many incidents that occurred to the One Hundred and Twelfth infantry which are

interesting.

He tells of how previous to the opening of the Argonne-Meuse offensive the

Fifty-sixth brigade, composed of the One Hundred and Eleventh and the One

Hundred and Twelfth infantries was stationed near Epieds, just north of the

Marne river. A battalion of the One Hundred and Eleventh was in a woods nearby

and apparently lost. The exact location of the battalion could not be learned

and the predicament was exasperating for the brigade artillery could not let go

at the Boche for fear of shelling the lost battalion of the One Hundred and

Eleventh. The one thing that had to be done was to locate the lost battalion

which was in command of Col. Shannon, also commander of the One Hundred and

Eleventh infantry. Accordingly on the morning of July 28, 1918, the first

battalion of the One Hundred and Twelfth under command of Maj. Smathers went

forward to locate the lost battalion. During the advance through the woods the

searching battalion was heavily shelled. It stopped to reconnoiter at a vantage

place in the forest and Capt. James Henderson of Oil City, Pa., with a patrol of

men was sent out to locate Col. Shannon. He went several hundred yards,

succeeded in locating the missing battalion and Col. Shannon, but when returning

with his command was struck by a Boche high explosive shell and killed

instantly. Location of the battalion, however, proved of decided advantage for

it permitted the brigade artillery to open fire on the Boche positions, and

removed the danger of striking the lost battalion.

MAJ. SMATHERS BECOMES FIRST IN COMMAND

During the second Marne offensive, Brig. Gen. Weigle,

in command of the Fifty-sixth brigade was promoted to major general and was sent

to the north to command a division. Col. George C. Rickards assumed command of

the Fifty-sixth and Maj. Smathers was promoted to first in command of the One

Hundred and Twelfth infantry regiment.

Just before the Twenty-eighth was relieved at the

Aisne, Maj. Smathers was gassed. He was leading an attack and going forward

under difficulties. The day was a hot one, and the Boche persisted in sending

over a gas shell every so often. “Mixing them up” the doughboys called it. Maj.

Smathers had trouble with his gas mask. The air was sultry and with the poorly

functioning mask the major could not get his breath. Accordingly he removed it

from his face for a minute or two and tried to adjust it. In so doing he inhaled

a slight quantity of gas which later necessitated his removal to the hospital.

He was confined there for three weeks but rejoined his command on Aug. 19.

After a short rest the Fifty-sixth brigade moved again

up into the front lines. On the night of Sept. 5, the One Hundred and Twelfth

was located in a small woods near the Vesle river. The divisional artillery was

in the same woods with a large number of artillery horses. During the afternoon

of the following day a Boche place flew overhead at an unexpected moment,

located the small concentration of troops and flew back again to his own lines.

That night, and it was not unexpected, bombing planes flew overhead and dropped

several huge bombs in the midst of the troops. Many were killed and injured and

50 artillery horses were killed.

On the night of Sept. 19 the One Hundred and Twelfth

infantry relieved a French regiment in the front lines of the Argonne sector.

For several days there was little action by either the Americans or the Germans

in the trenches opposite them. On Sept. 23, Lieut. Col. Bubb took command of the

regiment, and then on the 25th the entire division was moved up into a position

for attacking. The Argonne forest lay just ahead of the attacking armies and the

offensive was carefully planned. Zero hour was set for 5 a.m. on the 2th [sic].

The One Hundred and Eleventh infantry was in support of the One Hundred and

Twelfth which bore the brunt of the first attack. The Pennsylvanians went over

the top after an all night bombardment with the One Hundred and Eleventh

following closely. Throughout the entire day the fighting was severe.

About evening the regiment drew an intense machine gun

fire from the enemy, which resulted in heavy losses. The fighting regiment,

however, kept on, and Co. M, of the One Hundred and Twelfth, made up almost

entirely of Grove City boys, saved the day. Reconnoitering through the woods the

company captured 49 Boche artillerymen who were amount to[sic] man two German 77

m. guns. They had been placed in the edge of the woods and commanded a

considerable portion of the valley up which the conquering armies were marching.

With their tremendous capacity, the German gunners could have swept the invading

forces with such an intense fire that further progress would have been almost

impossible. Fortunately Co. M located them before they got into action.

Parallel with the conquests of the Twenty-eighth or

“Iron Division” are the deeds and fighting valor of the Eightieth division,

which was made up of men from Pennsylvania, Virginia and West Virginia. The

Eightieth division has been named the Blue Ridge division, its members being

recognized by a shield insignia of olive drab cloth upon which is superimposed

in the center three blue hills, representing the Blue Ridge mountains, all

outlined in white. This insignia is worn on the left shoulder of the uniform.

The greatest number of Pennsylvanians grouped together in separate unites of the

Eightieth were in the Three Hundred and Nineteenth, Three Hundred and Twentieth

infantries and Three Hundred and Fifteenth machine gun battalion.

The Blue Ridge division encountered its severest

fighting in the Argonne Meuse offensive from Sept. 26 on until the armistice. It

advanced to positions farther to the north than did the “Iron Division,” which

had a more strongly defended sector to fight against and was materially checked

by the concentration of troops around Varennes and Apremont. The part the two

divisions played in the Argonne fight was intended to be different. It was the

severe defeat of the Germans at Apremont and Varennes that permitted the

American armies to pursue the fleeing Hun so far to the north. Unlike the

Twenty-eighth division the Eightieth had no set battle front during the Argonne

fight, once the offensive was under way, but was shifted from one place to

another in the battle line. This shifting about subjected the Eightieth to many

long, wearisome marches.

FIRST BIG FIGHT OF THE EIGHTIETH

On Sept. 25, after having marched two nights from a

rest camp in the St. Mihiel sector, the Blue Ridge division reached the

Bethincourt sector of the Argonne Meuse offensive, which place they had been

accorded by the higher command. From the morning of Sept. 26 until the 29th they

advanced into the Argonne. From Oct. 4 to 12 they were in the Nantillois sector

of the Argonne-Meuse battle, and were moved forward on Nov. 1 to the St. Juvin

sector where they fought until the 6th.

The Blue Ridge fighters in their big drive of 17 days from Sept. 26 until

Oct.12, and in their last days of the offensive, of Nov. 1, to Nov. 8, reflected

the great manhood of the three Blue Ridge states, Pennsylvania, West Virginia

and Virginia. Recognition of the division’s great work was exemplified in the

promotion of its commander, Maj. Gen. Cronkhite who was placed in command of an

American army corps. The honor would probably have carried a three star

decoration had it not been for a war department order prohibiting promotion

under certain conditions. Maj. Gen. Sturgis, whose father held the same rank in

the Civil war, was placed in command of the Eightieth after the promotion of

Maj. Gen. Cronkhite and continued to command until the armistice was signed.

The One Hundred and Sixtieth brigade made up largely of

scrappers from Pittsburg and vicinity was fortunate in having for its commander

Brig. Gen. Lloyd M. Brett, who has been in active command of troops for 40

years. Gen. Brett was rated among the A.E.F. leaders as one of the very best.

His military genius was tempered so generously with fatherly action that he soon

became dear to the hearts of the 7,000 troops who made up his command.

USED EXCEPTIONAL STRATEGY

General Brett was exceptional in his methods of

fighting. H used military strategy that has not been surpassed and in very few

instanced did he adhere to the set forms that were commonly known by the allied

and German forces. Peculiar enough his many schemes resulted in decided

successes. In the capture of machine gun positions, for example, Gen. Brett

employed a brad ne method when it was found impracticable to use a flanking

movement. Gen. Brett’s orders were to have the men seek cover and re-form.

Meanwhile the artillery would be instructed to lay down a barrage over the

positions infested by enemy machine gunners, which would be so severe that the

Boches would be compelled to seek shelter in their dugouts. The order would be

given for the barrage to cease and suddenly before the Germans would get back to

their guns, Gen. Brett’s men would sweep down upon them and capture the Hun

crews in their shelters.

Another method employed by Gen. Brett to combat the

deadly machine gun was to resort to tactics which required the enemy gunners to

maintain a continuous fire. Machine guns are capable of keeping up a sustained

fire for a period of 20 minutes when they become too hot to be efficiently

handled. After the enemy would be kept busy firing for this period an advance

would be made upon them and their capture would be made possible at a minimum

cost.

It was not an infrequent occurrence, it is claimed, to

see Gen. Brett out in front in the thick of the fighting with the men of the

units in his command. He was where his men were, and he was often seen giving

water and aid to a fallen soldier. While at Camp Lee and during the fighting in

France he was fairly idolized by his soldiers and the men declare that he was

more of a father to them than an officer, as he always had their welfare at

heart. He was in touch with the men in the ranks and it was not an uncommon

sight to see him chatting with them.

|

|