|

A History of Pittsburg and Western Pennsylvania Troops in the War

By John V. Hanlon (Copyright 1919 by The Pittsburg Press)

Chapter VII

(The Pittsburg Press, Sunday, Feb. 16, 1919, pages 66-67)

Names in this chapter: Martin, Hitchman, Alexander, Baden, McLain, Coulter,

Ham, Brown, Morse, Hyde, Roosevelt

Here are a few of the brave leaders of units of the Twenty-eighth division from

Pittsburg and Western Pennsylvania who led our unconquerably doughboys in many

of their brilliant victories over the most famous regiments of the enemy. They

won upon many a bloody field their right to a high place in the esteem of all

mankind. Like the Conscript Fathers they wrote their names where time shall not

destroy and brought honor to their nation and their state.

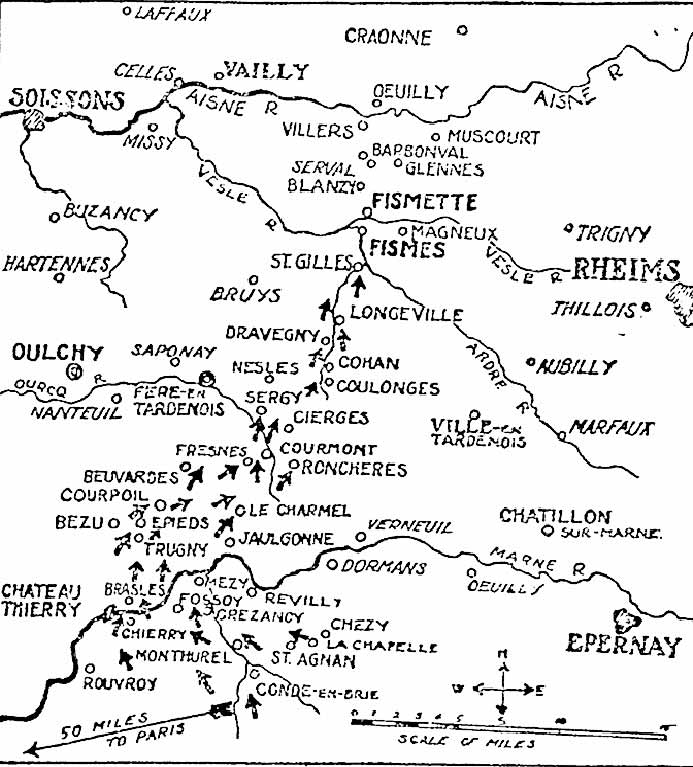

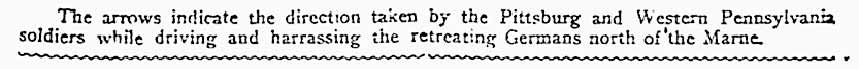

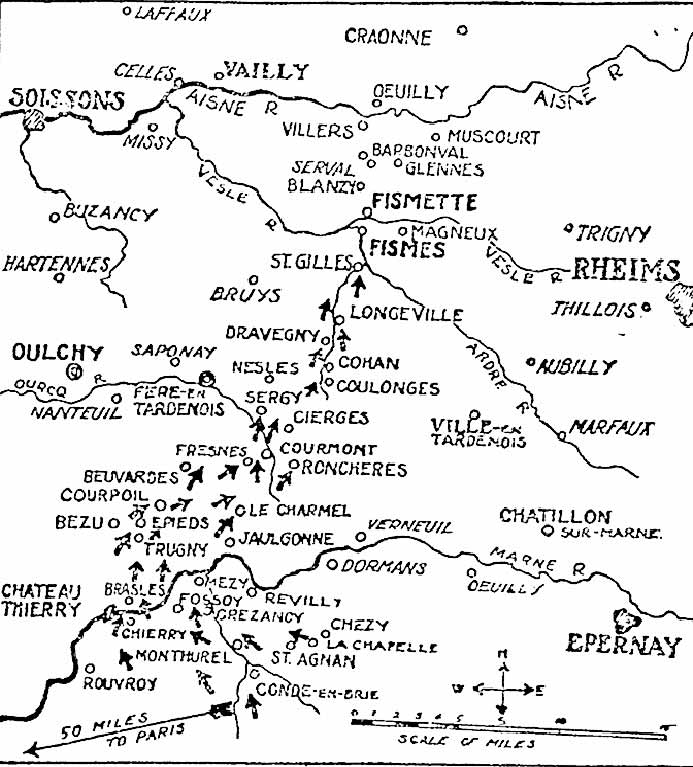

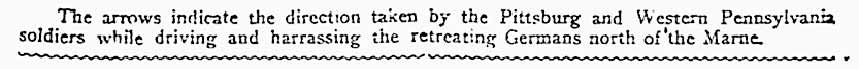

THE PITTSBURG AND WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA TROOPS OF THE TWENTY-EIGHTH DIVISION

CONTINUE THEIR DRIVE AGAINST THE RETREATING HUNS NORTH OF THE MARNE RIVER. ONE

HUNDRED AND SEVENTH ARTILLERY COMES INTO FIGHTING ZONE FOR FIRST TIME. OTHER

UNITS OF THE DIVISION ALSO ARRIVE. OUR BOYS PASS LIEUTENANT ROOSEVELT’S GRAVE

WHILE ON MARCH TOWARD VESLE.

The night of July 30, after the capture of Grimpelle’s

wood, the regimental headquarters of the One Hundred and Tenth was moved up to

Courmont, only 700 yards behind the wood. Maj. Martin summoned his staff about

him to work out plans for the next day. They were bending over a big table,

studying the maps when a six-inch shell struck the headquarters building

squarely. Twenty-two enlisted men and several officers were injured. Maj.

Martin; Capt. John D. Hitchman, Mt. Pleasant, the regimental adjutant; Lieut.

Alexander, the intelligence officer, and Lieut. Albert G. Baden, of Washington,

Pa., were knocked about somewhat, but not injured.

For a second time within a few days Lieut. Alexander had flirted with death. The

first time he was blown through an open doorway into the road by the explosion

of a shell that killed two German officers who were facing him, men he was

examining. This time, when the Courmont headquarters was blown up, he was

examining a German captain and a sergeant, the other officers making use of the

answers of the prisoners in studying the maps and trying to determine the

disposition of the enemy forces. Almost exactly the same thing happened again to

Lieut. Alexander. Both prisoners were killed and he was blown out of the

building uninjured.

“Getting to be a habit with you,” said Major Martin.

“This if the life,” said the lieutenant.

“Fritz hasn’t got a shell with Lieut. Alexander’s

number on it,” said the men in the ranks.

Capt. Lucius M. Phelps, Oil City

OLD TENTH MAN KILLED

The shell that demolished regimental headquarters was

only one of thousands with which the Boche raked our lines and back areas. As

soon as American occupancy of the wood had been established definitely, the Hun

turned loose an artillery “hate” that made life miserable for the

Pennsylvanians. In the One Hundred and Tenth alone there were 22 deaths and a

total of 102 casualties.

Capt. Charles L. McLain, Indiana, Pa.

The village of Sergy, just north of Grimpette’s wood,

threatened to be another severe test for our boys. Like some of the other

villages, it was understood to be strongly organized by the Germans who were

prepared to offer every possible resistance to the advancing Americans. The

Pennsylvanians were sent into the direct assault in company with regiments from

other divisions.

The utter razing of Epieds and other towns by artillery

fire in order the [sic] blast the Germans out of their stronghold led to a

decision to avoid such destructive methods whenever possible, because it was

French territory and too much of France had been destroyed already by the

ravaging Huns. The taking of Sergy was almost entirely an infantry and machine

gun battle.

It was marked, as so many other of the Pennsylvanians’

fights were, by the “never-say-die” spirit that refused to know defeat. There

was something unconquerable about the terrible persistence of the Americans that

seemed to daunt the Germans.

The American forces swept into the town and drove the

enemy forces slowly and reluctantly out to the north. The usual groups of Huns

were still in hiding in dugouts and cellars and other strong points, where they

were able to keep up a sniping fire on our men. Before the positions could be

moved up and organized the Germans were strengthened by fresh forces, and they

reorganized and took the town again. Four times this contest of attack and

counter-attack was carried out before our men established themselves in

sufficient force to hold the place. Repeatedly the Germans strove to obtain a

foothold again, but their hold on Sergy was gone forever. They realized this at

last and then turned loose the customary sullen shelling and shrapnel, high

explosives and gas.

MARVELOUS ENDURANCE

It was about this time that the Pittsburgers and

Western Pennsylvanians were suffering from lack of both food and sleep and

officers marveled at the way the men marched and fought when they must have been

almost at the end of their physical resources. There were innumerable instances

of their going 48 hours without either food or water. The thirst was worse than

the hunger and the longing for sleep was almost overpowering. The troops had

been advancing so fast that it was almost impossible for the commissary to keep

up with them and thus furnish the supplies regularly. Whenever opportunity

offered, the [sic] got a substantial meal, but these were few and far between.

The One Hundred and Ninth regiment had marched away to

the west to flank the village and reached a position in the woods just northwest

of Sergy. Scouts were sent forward to ascertain the position of the enemy, only

to have them come back with word that the town already was in the hands of the

One Hundred and Tenth. However, the One Hundred and Ninth was in for some trying

hours. A wood just north of Sergy was selected as an abiding place for the night

and, watching for a chance when Boche flyers were busy elsewhere, the regiment

made its way into the shelter and prepared to get a night’s rest.

They had escaped the eyes of the enemy airmen but,

unknown to the officers of the regiment the wood lay close to an enemy

ammunition dump, which the retiring Huns had not had time to destroy. Naturally

the German artillery knew perfectly the location of this dump and set about to

explode it by means of artillery fire.

PERILOUS HOURS

By the time the men of the One Hundred and Ninth,

curious as to the marked attention they were receiving from the Hun guns,

discovered the dump, it was too late to seek other shelter, so all they could do

was to contrive such protection as was possible and hug the ground, expecting

each succeeding shell to land in the midst of the dump and set off an explosion

that probably would leave nothing of the regiment but its traditions.

Probably half the shells intended for the ammunition

pile landed in the woods. Terrible as such a bombardment always is, the men of

the One Hundred and Ninth fairly gasped with relief when each screeching shell

ended with a bang among the trees, for shells that landed there were in no

danger of exploding that heap of ammunition. Strange as it may seem, the Boche

gunners were unable to reach the dump despite the fact that they knew exactly

where it was located and our boys began to have less respect for the accuracy of

the enemy artillery.

Lt. John H. Shenkel, Pittsburg

Lt. Marshall L. Barron, Latrobe, Pa.

In the night, a staff officer from brigade headquarters

had found Col. Brown and informed him that he was to relinquish command of the

regiment to become adjutant to the commanding officer of a port of debarkation.

Lieut. Col. Henry W. Coulter of Greensburg, took command of the regiment. Col.

Coulter is a brother of Brig. Gen Richard Coulter, one time commander of the old

Tenth Pennsylvania, and who was at that time a commander of an American port in

France. A few days later Col. Coulter was wounded in the foot and Col. Samuel V.

Ham, a regular army officer, became commander. As an evidence of the

vicissitudes of the Pennsylvania regiments, the One Hundred and Ninth had eight

regimental commanders in two months. All except Col. Brown and Col. Coulter were

regular army men.

Maj. Allen Donnelly

REASONS WHY MEN “FIDGETED”

August 1 and 2, the Pennsylvanians were relieved and

dropped back to rest for the two days. The men were nervous and “fidgety” to

quote one of the officers, for the first time since their first “bath of steel,”

south of the Marne. Both nights they were supposed to be resting they were

shelled and bombed from the air continuously, and both days were put in at the

“camions sanitaire,” or “delousing machines,” where each man got a hot bath and

had his clothes thoroughly disinfected and cleaned. There was evidently

“reasons” in large numbers why the men were “fidgety.”

Thus neither night or day could be called restful

although it was undoubtedly a great comfort for the men to be rid of their

well-developed crops of cooties and to have their bodies and clothes clean for

the first time in weeks. Anyway, the stop bolstered up the spirits of the men,

and when the two-day period was ended they were on the march again towards the

north. They were headed for the Vesle and worse things than they had ever

endured before.

It was about this time that the first of the

Pennsylvania artillery, a battalion of the One Hundred and Seventh regiment,

came into the fighting zone where the division was operating, and soon its big

guns began to roar back at the Germans in company with the French and other

American artillery.

The gun crews had troubles of their own in forging to

the front, although most of it was of a kind they could look back on later with

a laugh, and not the soul-trying, mind-searing experiences of the infantry.

The roads that had been so hard for the foot soldiers

to traverse were many times worse for the big guns. One of the Pennsylvania

artillery regiments of the Twenty-eighth division, for instance, at one time was

12 hours in covering eight miles of road.

Lt. Cedric H. Benz, Pittsburg

When it came to crossing the Marne, in order to speed

up the crossing the regiment was divided, half being sent farther up the river.

When night fell it was learned that the half that had crossed lower down had the

field kitchen and no rations, and the other half had all the rations and no

field kitchen to cook them. Other organizations came to the rescue in both

instances.

At 6 o’clock one evening, not yet having had evening

mess, the regiment was ordered to move to another town, which it had reached at

9 o’clock. Men and horses had been settled down for the night by 10 o’clock and,

as all was quiet, the officers went to the village. There they found an

innkeeper bemoaning the fact that, just as he had gotten a substantial meal

ready for the officers of another regiment, they had been ordered away, and the

food was ready, with nobody to eat it.

The hungry officers looked over the “spread.” There was soup, fried chicken,

cold ham, string beans, peas, sweet potatoes, jam, bread and butter and wine.

They assured the innkeeper he need worry no further about losing his food, and

promptly took their places about the table. The first spoonsful [sic] of soup

just were being lifted when an orderly entered, bearing orders for the regiment

to move on at once. They were under way again, the officers still hungry, by

11:45 o’clock, and marched until 6:30 a.m., covering 30 kilometres, or more that

18 miles.

WORK UNDER TERRIFIC FIRE

The One Hundred and Third Ammunition train also had

come up now, after experiences that prepared it somewhat for what was to come

later. For instance, when delivering ammunition to a battery under heavy

shellfire, a detachment of the train had to cross a small stream on a little

flat bridge, without guard rails. A swing horse of one of the wagons became

frightened when a shell fell close by. The horse shied and plunged over the

edge, wedging itself between the bridge and a small footbridge alongside.

The stream was in a small valley, quite open to enemy

fire, and for the company to have waited while the horse was gotten out would

have been suicidal. So the main body passed on and the caisson crew and drivers,

12 men in all, were left to pry the horse out. For three hours they worked,

patiently and persistently, until the frantic animal was freed.

They were under continuous and venomous fire all the

while. Shrapnel cut the tops of trees a bare 10 feet away. Most of the time they

and the horses were compelled to wear gas masks, as the Hun tossed over a gas

shell every once in a while for variety – he was “mixing them.” The gas hung

long in the valley, for it has “an affinity,” as the chemists say, for water,

and will follow the course of a stream.

High explosives “cr-r-rumped” in places within 200

feet, but the ammunition carriers never even glanced up from their work, nor

hesitated a minute. Just before dawn they got the horse free and started back

for their own lines. Fifteen minutes later a high explosive shell landed fairly

on the little bridge and blew it to atoms.

SIGNALMEN DO HEROIC WORK

The One Hundred and Third Field Signal battalion,

composed of companies chiefly from Pittsburg, but with members from many other

parts of the state, performed valiant service in maintaining lines of

communication. Repeatedly men of the battalion, commanded by Maj. Fred G.

Miller, of Pittsburg, exposed themselves daringly in a welter of fire to extend

telephone and telegraph lines, sometimes running them through trees and bushes,

again laying them in hastily scooped out grooves in the earth.

Frequently communication no sooner was established than

a chance shell would sever the line, and the work was to do all over again. With

cool disregard of danger, the signalmen went about their tasks, incurring all

the danger to be found anywhere – but without the privilege and satisfaction of

fighting back.

Under sniping rifle fire, machine gun and big shell

bombardment and frequently drenched with gas, the gallant signalmen carried

their work forward. There was a little of the picturesque about it, but nothing

in the service was more essential. Many of the men were wounded and gassed, a

number killed, and several were cited and decorated for bravery.

When the grip of the enemy along the Ourcq was torn

loose there was no other stopping place short of the Vesle, and so he hurried

back toward this point as fast as he could move his armies and equipment.

Machine gun and sniping rear guards were left behind to protect the retreat and

impede the pursuers as much as possible, but even these rear guards did not

remain very long and it was difficult at times for the Americans to keep in

contact with Jerry.

The Thirty-second division, composed of Michigan and

Wisconsin national guards, had slipped into the front lines and with regiments

of the Rainbow division pressed the pursuit. The Pennsylvania regiments, with

the One Hundred and Third engineers and the One Hundred and Eleventh and One

Hundred and Twelfth infantries leading, followed by the One Hundred and Ninth

and then the One Hundred and Tenth infantry, went forward in their rear, mopping

up the few Huns the Thirty-second had left in its wake, and who still showed

fight.

GET HUN ON THE RUN AT LAST

It had begun to rain – a heavy dispiriting downpour,

such as Northern France is subjected to frequently. The fields became small

lakes and the roads, cut up by heavy traffic, were turned to quagmires. The

distorted remains of what had been wonderful old trees, stripped of their

foliage and blackened and torn by the breaths of monster guns, dripped dismally.

In all that ruined, tortured land of horror there was not one bright spot, and

there was only one thing to keep up the spirits of the soldiers – the Hun was

definitely on the run.

Capt. W. R. Dunlap, Pittsburg

The men were wading in mud up to their knees, amid the

ruck and confusion of an army’s wake and always drenched to the skin. They

trudged wearily but resolutely forward, seemingly inured to hardships and

insensible to ordinary discomforts. They were possessed on only one great

desire, ant that was to come to grips once more with the hateful foe and inflict

all the punishment within their power in revenge for the gallant lads who had

gone from their ranks.

And during this march there was hardly a moment when

they were not subjected to long-distance shelling for the Huns strafed the

country to the southward in the hope of hampering transport facilities and

breaking up marching columns. At all times Boche fliers passed overhead,

sometimes sweeping low enough to slash at the columns with machine guns, and, at

frequent intervals, releasing bombs. There were casualties daily, although not,

of course, on the same scale as in actual battle.

PASS ROOSEVELT’S GRAVE

Through Coulonges, Cohan, Dragegny, Longeville, Mont-Sar-Courville

and St. Gilles they plunged on relentlessly, and close by the hamlet of Chamery,

near Cohan, our boys passed by the grave of that intrepid soldier of the air,

Lieut. Quentin Roosevelt, gallant son of that great American, the late Col.

Theodore Roosevelt. Lieut. Roosevelt had been brought down here by an enemy

airman a few weeks before and was buried by the Germans.

French troops, leading the allied pursuit, had come on

the grave first and immediately established a military guard of honor over it.

They also supplanted the rude cross and inscription over it which had been

erected by the Germans, with a neater and more ornate marking. But it was always

thus with both men and women of France. The grave of an American was always

sacred to them and to care for it and do honor to the brace man who rested

therein was a work dear to their hearts.

When the Americans arrived the French guard was withdrawn and the

comrades-in-arms from the dead lieutenant’s own country mounted guard over the

last resting place of the son of a former president.

Below Longeville the Pennsylvanians came into an area

where the fire was intensified to the equal of anything they had passed through

since leaving the Marne. All the varieties of projectiles the Hun had to offer

were turned loose in their direction, high explosives, shrapnel and gas. Once

more the misery and discomfort of the gas mask had to be undergone, but by this

time the Pennsylvanians had learned well and truly the value of that little

piece of equipment and had a thorough respect for the doctrine that, unpleasant

as it might be, the mask was infinitely better than a whiff of that dread,

sneaking, penetrating vapor with which the Hun poisoned the air.

Lt. Wm. H. Allen, Pittsburg

ON THE WAY TO FISMES

The objective point on the Vesle river for the

Pennsylvanians was Fismes. This was a town near the junction of the Vesle and

Andre rivers, which before the war had a population of a little more than 3,000.

It was on a railroad running through Rheims to the east. A few miles west of

Fismes the railroad divides, one branch winding away southwestward towards

Paris, the other running west through Soissons and Compiegne. The town was one

of the largest German munition depots of the Soissons-Rheims sector and second

only in importance to Soissons itself. The past tense is used, because in the

process of breaking the Hun’s grip on the Vesle both Fismes and Fismette, which

was just across the river, were virtually wiped off the map. Here was the Huns’

Vesle river barrier, and when he was shaken loose he had to move hastily

northward towards the next barrier, the Aisne. The railroad in Fismes and its

vicinity runs along the top of an embankment, raising it above the surrounding

territory. There was a time, before the Americans were able to cross the

railroad, that the embankment became virtually the barrier dividing redeemed

France from the darkest Hunland along that front. At night patrols from both

sides would move forward to the railroad, and burrowed in holes – the Germans in

the north side and the Americans in the south – would watch and wait and listen

for signs of an attack.

PATROLS CLOSE TOGETHER

Each knew the other was only a few feet away; at times,

in fact, they could hear each other talking, and once in a while defiant

bandiage would be exchanged in weird German from the south and in ragtime,

vaudeville English from the north. Appearance of a head above the embankment on

either side was a signal for a storm of lead and steel.

The Americans had this advantage over the Germans: They

knew the Huns were doomed to continue their retreat, and that the holdup along

the railroad was only temporary, and the Germans now realized the same thing.

Therefore, the Americans fought triumphantly, with vigor and dash; the Germans,

sullenly and in desperation.

One man of the One Hundred and Tenth went to sleep in a

hole in the night and did not hear the withdrawal just before dawn. Obviously

his name could not be made public. When he woke it was broad daylight, and he

was only partly concealed by a little hole in the railroad bank. There was

nothing he could do. If he had tried to run for his regimental lines he would

have been drilled like a sieve before he had gone 50 yards. Soon the German

batteries would begin shelling so he simply dug deeper into the embankment.

“I just drove myself into that bank like a nail,” he

told his comrades later. He got away the next night.

FOUR DAYS IN “NO MAN’S LAND”

Richard Morse, of the One Hundred and Tenth, whose home

is in Harrisburg, went out with a raiding party. The Germans discovered the

advance of the group and opened a concentrated fire, forcing them back. Morse

was struck in the leg and fell. He was able to crawl, however, and crawling was

all he could have done anyway, because the only line of retreat open to him was

being swept by a hail of machine gun bullets. As he crawled he was hit by a

second bullet. Then a third one creased the muscles of his back. A few feet

farther and two more struck him, making five in all.

Then he tumbled into a shell hole. He waited until the

threshing fire veered from his vicinity and he had regained a little strength,

then crawled to a better hole and flopped himself into that. Incredible as it

may seem, he regained his own lines the fourth day and started back to the

hospital with every prospect of a quick recovery. He had been given up for dead,

and the men of his own and neighboring companies gave him a rousing welcome. He

had nothing to eat during those four days, but had found an empty tin can, and

when it rained caught enough water in that to assuage his thirst.

Corp. George D. Hyde, of Mt. Pleasant, Co. E, One

Hundred and Tenth, hid in a shell hole in the side of the railroad embankment

for 36 hours on the chance of obtaining valuable information. When returning a

piece of shrapnel struck the pouch in which he carried his grenades. Examining

them, he found the cap of one driven well in. It was a miracle it had not

exploded and torn a hole through him.

“You ought to have seen me throw that grenade away,” he

said.

|