|

A History of Pittsburg and Western Pennsylvania Troops in the War

By John V. Hanlon (Copyright 1919 by The Pittsburg Press)

Chapter VI

(The Pittsburg Press, Sunday, Feb. 9, 1919, pages 70-71)

Names in this chapter: Muir, Rickards, Miller, Shannon, Price, Martin, Kemp,

Meighan, Coulter, Bullitt

The rough and ready commander of the Twenty-eighth

division, Maj. Gen. C. A. Muir – “Uncle Charlie” the boys called him – and some

of the principal officers who led the Pittsburg and Western Pennsylvania troops

to glory in the great drive against the Germans in the Soissons-Rheims Salient.

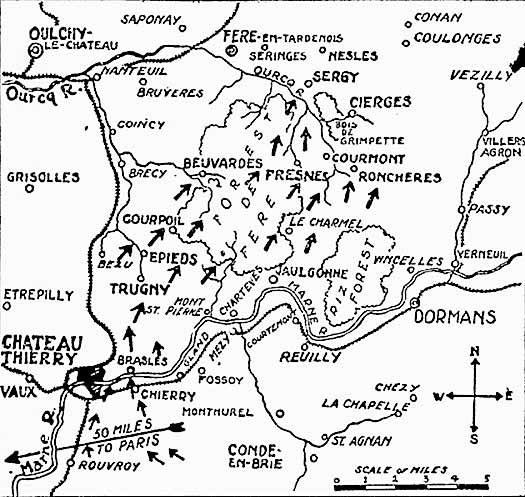

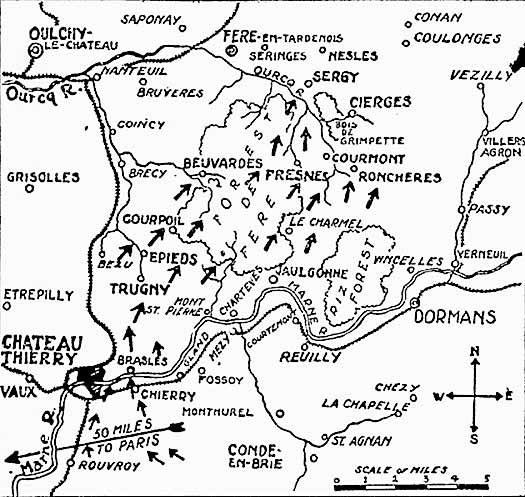

THE ADVANCE OF THE TWENTY-EIGHTH DIVISION NORTHWAS FROM

CHATEU-THEIRRY WAS MARKED BY SOME STREUOUS FIGHTING, FOR THE GERMANS MADE A

STRONG EFFORT TO HOLD BACK THE AMERICANS IN ORDER TO GET THEIR ARMY AND WAR

MATERIAL OUT OF THE SOISSONS-RHEIMS POCKET. THE TAKING OF RONCHERES, WHICH FELL

TO THE LOT OF THE ONE HUNDRED AND TENTH REGIMENT, WAS A PARTICULARLY HARD TAKS

AND ITS CAPTURE LATER OF THE BOIS DE GRIMPETTE HAS BEEN CHARACTERIZED AS ONE OF

THE BITTEREST AND BLOODIEST BATTLES OF THE WAR.

Maj. Gen. C. A. Muir

The taking of Roncheres fell to the lot of the One

Hundred and Tenth Regiment. This town like all the others was strongly held by

the Germans who had massed machine guns and fresh infantry for the sole purpose

of making its capture as costly as possible for the Americans. Like every other

village in this section the Boche had no intention of retaining it, but was

concerned mostly in holding back our boys as long as possible in order to

successfully get his armies and material out of the Soissons-Rheims salient.

With their characteristic disregard for every finer

instinct, the Germans had made the church the center of their resistance. This

church stood in such position as to front on an open square in the center of

town, and the enemy was thus able to command the roads which entered this square

from different directions.

Every building, every wall, tree or fence corner sheltered a sniper or machine

gun and most of the enemy, at this point, kept up such a determined resistance

that they died where they stood. In some instances, when an American was close

enough to point the cold steel of his bayonet at a Boche up would go his hands

with a cry of “kamerad.” There was always something the threat of the bayonet

which the Hun could never withstand. However, it may as well be set down here as

in the future that the men of the One Hundred and Tenth took few prisoners, for

they did not trust the cry of “kamerad!” They usually disposed of the foe with

scant ceremony.

Col. George C. Rickards

GERMAN WARFARE

On previous occasions they had learned that the Hun was

never to be trusted. They had lost comrades as the result of this treachery

because a Boche might still have his hands in the air, pleading for mercy and at

the same time have his foot on the lever of a machine gun. His hands in the air

were frequently but a decoy to lure our men within close range of the deadly

weapon which he could set going with this foot.

So in Roncheres our men of the One Hundred and Tenth

played the old game of hide and seek and they were always “it.” To be tagged

meant death for the Hun. They moved steadily from building to building until

they came in range of the village church. Then their progress was stayed for a

time.

On the roof of the church was a cross made from some

kind of red stone. Behind it the Germans had planted guns. Three guns were

hidden in the belfry from which the Huns had removed the bells and shipped them

into Germany, and stationed in every nook and cranny of the magnificent gothic

walls and balconies were snipers, machine gunners or artillerymen with small

cannon.

After much careful work sharpshooters of the One

Hundred and Tenth finally picked off the Germans behind the cross, but the

little fortress in the belfry still held out and was capable of doing

considerable execution. Detachments set out to work their way around the outer

edge of the town and thus surround the church. Our Pennsylvanians would dodge in

and out from street corner to street corner and from building to building ever

seeking to escape the quick eye of the enemy snipers. When they found a house

with sufficiently strong walls to withstand the foe bullets, sharpshooters would

be stationed there to keep the Hun fire down until some of the men could rush

into the next house. It was fight every step of the way.

YANKEE STRATEGY WINS

When the Pennsylvanians came to the roads which

radiated from the square to the four corners of the village they had to pause

and work out a new plan of attack, for it was necessary to cross these roads in

order to advance further and to attempt the feat would have been nothing less

than suicidal in view of the hurricane of bullets with which they were

continually swept.

When sufficient detachments of our men had reached the

various corners to provide enough strength for a sortie a barrage of rifle

bullets was put on the Germans. Sharpshooters were stationed at every possible

point where they could watch the Boche, and they commenced to pump lead into

every place where they believed the German bullets were coming from. They did

not give the foe a chance to show himself, but kept showering him with bullets.

In this way the Hun fire was reduced to a minimum and the rush across the

streets was made. Gaining the other side the Pennsylvanians worked closer to the

church along another row of houses, cleaning up the enemy as they progressed. It

was slow and dangerous work but our boys never flinched.

During all this fighting the church remained the

dominating figure, as it had been of the village landscape so many years. Its

stout stone walls, gray with age and built to last for centuries, offered the

ideal shelter for the vandals who were desecrating its sacred precincts. Before

our men could do anything more it was imperative that the enemy therein must be

cleaned out.

In previous fighting in this territory a German shell

had opened a convenient hole in the masonry at the rear of the church and groups

of the Pennsylvanians worked their way as close to this spot as possible without

exposing themselves to the Boche in the church. Then they put down another rifle

barrage using the same tactics whereby they were able to get across the fire

swept streets. A detachment of the One Hundred and Tenth rushed for this hole in

the wall and rapidly filtered through into the interior which shortly became a

charnel house for the Hun. They soon cleaned the foe out and then tackled the

belfry where the little group of Boche still persisted in the defense.

TOOK CHURCH, BUT NO PRISONERS.

One man led the way up the winding stone stairway,

fighting every step of the way, and strange to relate he was able to reach the

top despite the fact that many below him were caught in the rain of missiles.

Hurled down by the frantic Huns who thus sought to stay this implacable advance.

When a few of our men had gained the top of the stairs

one German junior officer, presumably in command of the group, leaped from the

belfry to his death on the stones in the courtyard below. Then the three

remaining Huns set up a loud plea for mercy, wildly waved their arms in the air,

and yelled “kamerad!” Whether or not their pleas were granted will probably

never be definitely ascertained as the Pennsylvanians who were there do not have

any clear perception as to just what happened. However, the idea seems to

prevail that no prisoners were taken in the church – at least some of the men

say they didn’t see any brought out.

After the capture of the church it was a comparatively

easy matter to mop up the rest of the town, but even then our boys had only a

brief breathing spell, for the regiment was soon on the march again, swinging

over towards Courmont which was reached just in time to help the boys of the One

Hundred and Ninth in wiping out the last machine gunners there.

At Courmont our Pennsylvanians had almost reached the

Ourcq river where the enemy had taken advantage of the natural defenses on the

other side of the stream to make a determined stand. In fact here had been

constructed a second line of defense. And here was fought one of the most

stubborn and bloodiest battles of the war.

THE CROSSING OF THE OURCQ

Our men faced the Guardsmen, Jaegers and Bavarians with

contingents of Saxon machine gunners – the whole making up the flower of the

troops under command of the crown prince. They had orders not to give away even

a foot of ground before the Americans. The enemy fought sullenly and with all

the traditional vigor of the famed units engaged, but they could not hold

against the irrisistable [sic] Pennsylvanians.

Col. George E. Kemp

The crossing of the Ourcq had been described as one of

the finest feats accomplished by the Americans in the way. The Ourcq itself was

negligible as an obstacle to the troops, for it is really on a little stream and

the Americans called it a “creek.” At this point it is only about 20 feet wide

and six inches deep. But what makes the Ourcq formidable is the heights beyond.

The river being old, it has worn itself a deep bed with high banks on each side.

Just north of Courmont and on the opposite side of the

Ourcq is the Bois de Grimpette, a small wooded tracks, and here was staged the

most ferocious fight of the entire line. This particular phase of the battle has

been described as “the One Hundred and Tenth’s own show.”

It was one of those feats which become regiments

traditions, the tales of which are handed down for generations within regimental

organizations and in later years become established as standards towards which

future members may aspire with only small likelihood of attaining.

COMPARED WITH BELLEAU

The operation, in the opinion of many high officers who

witnessed it, compared most favorably with the never-to-be-forgotten exploit of

the Marines in the Bois de Belleau.

There were these differences: First, the Belleau Wood

fight occurred at a time when all the rest of the Western Front was more or less

inactive, but the taking of Grimpettes Wood came in the midst of a general

forward movement that was electrifying the world, a movement in which miles of

other front bulked large in public attention; second the taking of Belleau was

one of the very first real battle operations of Americans, and the Marines were

watching by the critical eyes of a warring world to see how “those Americans”

would compare with the seasoned soldiery of Europe; third, the Belleau fight was

an outstanding operation, both by reason of the vital necessity of taking the

wood in order to clear the way for what was to follow and because it was not

directly connected with or part of other operations anywhere else.

“The Germans have a strong position in Grimpette

Woods,” the One Hundred and Tenth was told. “Take it.” The regiment by this time

had learned something of German “strong positions,” and so the men prepare to

tackle a stiff job. In the early days of their fighting they had gone about such

jobs with an utter disregard of the enemy machine guns, but they were not more

experienced and knew that such recklessness did them no good and was of no

service to America because of the useless sacrifices such tactics entailed.

Yet when they looked over the territory which they were

expected to rid of the Hun they were convinced that they had no alternative but

to do just that thing and face a well organized and strongly held enemy

position. Grimpette Woods was fairly bristling with every sort of Hun weapon and

gunners were chained to their weapons. The underbrush was laced through and

through with barbed wire, concealed strong points checker-boarded the dense,

second-growth woodland. When the Pennsylvanians took one next of machine guns

they found themselves fired on from two others. This mace of machine guns and

snipers was supplanted by countless mortars and one-pounder cannons.

INTO A HELL OF FIRE

The most difficult task in connection with the capture

of this wood, the taking of the hilly section, was assigned to the One Hundred

and Tenth, and the other regiment of the Fifty-fifth Infantry brigade, the One

Hundred and Ninth, was ordered to clean out the lower part.

It was a murderous undertaking, for the nearest “cover”

from the edge of the wood was at Courmont, more than 700 years away. The men

rushed out from the protection of the buildings in Courmont in the most perfect

and approved wave formations and were immediately met by a hurricane of bullets.

Some of the men later said that it seemed almost like a solid wall in places.

There was not even as much as a leaf to protect them. The rattle of the hundreds

of machine guns in the woods gradually increased in volume until they blended

into one solid roar, and the one-pounder cannon played havoc with our troops,

while German airmen, who had almost complete control of the air in that

vicinity, soared as low as 100 feet from the ground and poured a stream of

machine gun bullets into the ranks of those dauntless Pennsylvanians. The airmen

also raked the ranks with high explosive bombs. Our men were forced to organize

their own air defense and proceeded to use their rifles, but without much

deterrent effect on the Hun flyers.

How any man ever lived in that welter of fire is a

mystery, but a few won to the edge of the wood, and, flinging themselves down on

the ground, dug in. A few of the others who were nearer the wood than the town

did not attempt to retrace their steps in that awful rain of lead and steel, but

flung themselves into shell holes or an slight depression in the ground which

offered even temporary safety. The high officers recalled the attack, realizing

that the losses were beyond reason for the value of the objective. However,

neither officers or men of the One Hundred and Tenth were satisfied, and they

all pleaded for another chance. No matter what the cost this was Western

Pennsylvania’s day against the Hun and the task had not been performed in

accordance with all the traditions of that section of the great commonwealth.

Furthermore, there were living and wounded comrades out there in the Gehena of

fire who could not long be left unsupported.

THEN THEY FOUGHT AGAIN

The higher officers were impressed by this plea, and

after the men had secured a breathing spell they were allowed to have another

try. Then forming again they set their teeth and plunged into that storm of lead

and steel. They didn’t even have adequate artillery support, for the guns were

busy elsewhere and many batteries were still struggling over the ruined roads in

an effort to get near the front.

One the second attack another handful of men managed to

filter through to the edge of the wood, but the main attacking force was driven

back. It seemed almost as if noting could withstand that withering enemy blast

of fire. For three more times our boys, undaunted, attempted to cross that

bullet-swept stretch of ground, and each time they were forced back to the

shelter of Courmont.

After this fifth attack headquarters had received

information, July 30, 1918, that the artillery had come up and would put a

barrage on the wood. Maj. Martin, in command of the One Hundred and Tenth, when

he heard this said: “Fine: we will clean the place up at 2:30 o’clock this

afternoon.” And this is just what the regiment did.

The artillery put down a terrific barrage on the wood

and the Huns were driven to shelter, while holes were opened in the near side of

the wood and the wire was cut in many places. The few Pennsylvanians who had won

their way to the edge of the wood in the previous attacks had to dig in deeper

and find whatever shelter they could, for they were forced to withstand the

rigors of their own barrage. It was a terrible experience to have to undergo the

bombardment of their own guns.

SIXTH ATTACK SUCCESSFUL

Then came the order to advance in the sixth assault on

Grimpette Woods, and as the men rushed forward the barrage lifted. The big guns

had given just the added weight to carry them across the open space, and they

were well on their way when the Germans were able to come out of the dugouts and

take position at their guns. The first wave of Americans, angry and yelling like

Indians, was on them before they could do much damage.

That was the beginning of the end for the Germans in

the Bois de Grimpette, for our boys went through it in a hurry with man against

man, using the bayonet unsparingly and unmercifully. Some prisoners were sent

back, but this was the exception rather that the rule, and the burial squads

laid away more than 400 German bodies in the Grimpette. The American loss in

cleaning up the wood was hardly a tithe of that. It was truly a dashing and

heroic bit of work, typical of the gallantry and spirit of our men.

After the first attack on the wood had failed First

Sergt. William G. Meighan, of Waynesburg, Co K, One Hundred and Tenth regiment,

in the lead of his company, was left behind when the recall was sounded. He had

flung himself into a shell hole in the bottom of which water had collected. The

machine gun fire of the Germans was low enough to “cut the daisies,” as the men

remarked. Therefore, there was no possibility of crawling back to the lines. The

water in the hold in which he had sought shelter attracted all the gas in the

vicinity, for Fritz was mixing gas shells with his shrapnel and high explosives.

The German machine gunners had seen the few Americans

who remained on the field, hiding in shell holes, and they kept their guns

spraying over those refuges. Other men had to don their gas masks when the gas

shells came over, but none seem to have undergone the experience Sergt. Meighan

did.

THE DREADED GAS MASK

It is impossible to talk intelligently or to smoke

inside a gas mask. A stiff clamp is fixed over the nose and every breath must be

taken through the mouth. Soldiers adjust their masks only when certain that gas

is about. They dreaded gas more than anything else the German had to offer, more

than any other single thing in the dread category of horrors with which the

Kaiser distinguished this war from all other wars in the world’s history. Yet

the discomfort of the gas mask, improved as the present model is over the device

that first intervened between England’s doughty men and a terrible death, is

such that it is donned only in dire necessity. Soldiers hate the gas mask

intolerably, but they hat gas even more.

For 15 hours he was forced to crouch in the water in

this shallow hole with his gas mask on, but despite the terrible ordeal he still

had plenty of fight left in him. When in a later attack on the wood Co. K

reached the point where Sergt. Meighan was concealed he discovered that the last

officer of the first wave had fallen before his shelter was reached. Being next

in rank he promptly signaled to the men that he would assume command, and led

them in a gallant assault on the enemy position.

FOUGHT TO HIS DEATH

There were also many other men of the One Hundred and

Tenth who displayed marked gallantry and that spirit of sacrifice which made our

boys so successful in the various enterprises in which they engaged. Lieut.

Richard Bullitt, of Torresdale, an officer of Co. K, was struck in the thigh by

a machine bullet in one of the first attacks, and although unable to walk he

crawled 100 yards to where there was a squad with an automatic rifle out of

commission and which the men could not operate. The corporal in charge of the

rifle squad seems to have been the only one of the men who could operate it. He

had been killed and Lieut. Bullitt quickly had the gun throwing death into the

German ranks. While he was operating the automatic five more bullets struck him

but he kept on. He waved the stretcher bearers away who wanted to take him to

the rear, but finally another bullet struck him in the forehead and killed him.

After the wood was completely in our hands a little

column was observed moving across the open space towards Courmont. When it go

close enough it was seen to consist entirely of unarmed Germans. Staff officers

were just beginning to fuss and fume about the ridiculousness of sending a party

of prisoners back unguarded when they discovered a very dusty and a very

disheveled American officer bringing up the rear with a rifle held at the

“ready.” He was Lieut. Marshall S. Baron, Latrobe, of Co. M. There were 67

prisoners in his convoy and most of them he had taken personally.

|