|

A History of Pittsburg and Western Pennsylvania Troops in the War

By John V. Hanlon (Copyright 1919 by The Pittsburg Press)

Chapter III

(The Pittsburg Press, Sunday, Jan. 19, 1919, pages 66-67)

Names in this chapter: Foch, Thompson, Kemp, Brown, Truxel, Fish, Cousart,

Mackey, Smith, Hayman

PITTSBURG AND WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA TROOPS MOVE CLOSER TO FRONT LINE IN SUPPORT

OF FRENCH. TWO COMPANIES FROM OLD TENTH FILL GAP IN FRENCH FRONT LINE. THE

OPENING OF THE BATTLE OF THE MARNE, WHERE PENNSYLVANIA REGIMENTS RECEIVE FIRST

BAPTISM OF FIRE.

During the first days of July, 1917, Marshal Foch had

been gradually working the Germans into a position where there was only one

loophole towards which to launch the forthcoming drive, and the supreme

commander wanted the enemy to make just that move. The direction was straight

south at the tip of the Soissons-Rheims salient and in the direction where the

Pittsburg and Western Pennsylvania troops were stationed. Here Marshal Foch set

a trap, for although the lines were only thinly held by the French, he had the

Americans in reserve. He had already tested the valor of some of the

Pennsylvanians and the other American forces assembled in that section and he

was supremely confident that the great moment had arrived.

The Germans would cross the Marne, but they wouldn’t go

fat until they met those unyielding lines of doughboys. There would be a violent

clash as the Americans unloosed their pent up energy, and then the Germans would

find themselves on the defensive and making a hurried effort to get back on the

other side of the Marne. That was the way Marshal Foch expected the affair to

work out. He was banking on the Americans and the Americans did not fail him.

Then it was that the German military leaders realized for the first time that

the war was lost to them. Ger. Pershing said it was the turning point of the

war, and the ex-crown prince has since admitted that he knew it was the

beginning of the end for Germany. The Boche had never met an “iron” division.

July 5, 1917, there was a noticeable stir at brigade

headquarters. Then messengers began to hurry to the various regimental

headquarters and soon the word was passed along that the regiments were to move

up in closer support of the French lines. This was cheering news indeed. At last

the Pittsburgers and Western Pennsylvanians were actually going up into the zone

of fire where the great shells would go screeching overhead and even fall

menacingly near at times.

Early on the morning of July 6, 1917, the One Hundred

and Tenth, One Hundred and Eleventh and the engineers shouldered their equipment

and moved forward to the positions assigned them. The One Hundred and Twelfth

was held in reserve.

During the journey one of the soldiers was seen to

reach up and pull a branch from a tree alongside the road. He struck a

leaf-covered twig in his cap with the remark that “now I am camouflaged,” The

flies were troublesome and his comrades soon perceived that the soldier with the

“camouflage” was not bothered. Then there was a rush for head decorations until

the regiments looked like the famous Italian Bersagleri. The Bersaglieri wear

plumed hats. The One Hundred and Tenth, One Hundred and Eleventh and the

engineers arrived at their positions without incident except an occasional

reminder from the Boche in the shape of a shell which passed overhead and

exploded in the distance. The cannonading also became ever louder and increased

in volume as the troops advanced.

DODGING THE GERMAN SHELLS

The One Hundred and Ninth Regiment did not fare so

well, for it encountered an area in its march northward which was being

vigorously shelled by the Boche. The regiment had passed the little village of

Artonges where the Dhuys creek joins the road and then follows along the valley

towards Pargny-la-Dhuys. The latter town was almost in sight when a shell burst

in a field a few hundred yards away. Then came an officer rushing from brigade

headquarters with orders for the regiment immediately to seek cover in the woods

nearby. The Germans were raking the countryside in an attempt to locate French

batteries. The shelling kept the regiment in the woods until July 10, 1917. Then

came orders to advance and after going through what was left of Pargny, after

that terrific shelling, the regiment was ordered off the road into a long

ravine.

Then the bombardment started again and the men realized

that it was much safer to have the protection of the ravine than to be caught on

the shell-swept open road. Three days the enemy kept up the fire. July 13, 1917,

when the hour for “taps” arrived and no orders for the night had been given, the

men realized that something was going to happen. At midnight the regiment was

formed in light marching order – no heavy packs, no heavy clothes, nothing but

fighting equipment and two days’ rations.

Then the column moved northward through the night; up

toward the Marne while star shells shed a glow from the sky and shrapnel and

high explosives were being showered in all directions. When the column reached

the designated position to the left of the engineer regiment of the division the

men were told to “dig in!”

The next day was July 14, “Bastile [sic] Day,” France’s equivalent for our

Independence Day, and from indications the Pennsylvanians believed it was to be

a real celebration.

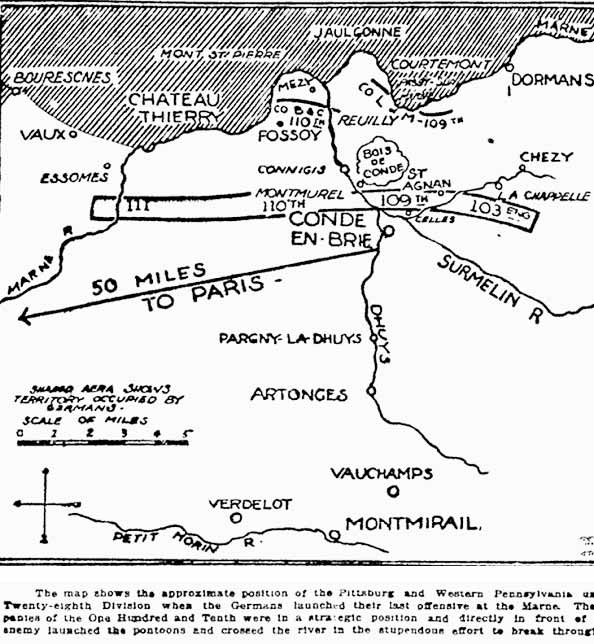

Bastile Day, the Pennsylvania regiments spent in their

hastily constructed trenches about two miles from the front line which was

directly along the valley of the Marne. The accompanying map will convey some

idea as to the location of the Pittsburgh and Western Pennsylvania soldiers.

Their line stretched out over quite a distance and with French regiments between

each of the regiments of the Twenty-eighth Division. The engineers were

operating as infantry.

All day long the Pennsylvanians waited patiently for

something to happen, but the only excitement was the screech of the shells

overhead. Towards evening on Bastile Day runners arrived from brigade

headquarters with orders for Col. Brown of the One Hundred and Ninth and Col.

Kemp of the One Hundred and Tenth to dispatch two companies from each regiment

to fill little gaps in the French lines on the front. Col. Kemp forwarded his

message to Maj. Joseph H. Thompson, of Beaver Falls, commanding the first

battalion of the One Hundred and Tenth. Maj. Thompson selected Companies B, of

New Brighton and C, of Somerset. Company B was commanded by Capt. William Fish

and Company C by Capt. William C. Truxel.

Company L and Company M of the One Hundred and Ninth

were selected and commanded by Capts. James B. Cousart, of Philadelphia and

Edward P. Mackey, of Williamsport.

The two companies of the old “Fighting Tenth” were

placed in the line back of Fossey and Mezy, directly in the great bend of the

river and with the One Hundred and Thirteenth French regiment. The two companies

of the eastern Pennsylvania regiment were place near Passy-sur-Marne and

Courtemont-Varennes. It is near this point that the Dhuys river flows into the

Marne and the Dhuys separated the companies of the two regiments. Fossoy, the

farthest west of the towns, is only four miles from Chateau-Thierry and Passy is

about four miles farther east.

The reasons for thus plugging the holes in the French

lines were many. Marshal Foch had been giving the Germans a jolt here and there

until he had them in such a position that the next outbreak was almost sure to

occur directly southwest of Chateau-Thierry. The heavy concentration of French

troops around Chateau-Thierry had weakened the French front line at this point.

NO SLEEP FOR 48 HOURS

Here it was expected that the Pennsylvania troops would

receive their baptism of fire, for they would be directly in the zone of

operation. French staff officers accompanied the Americans to the front line and

so distributed them that there was alternately a French regiment and a

Pennsylvania company. The Pennsylvanians were now operating directly with the

French troops and under French higher command.

Between the advanced companies and the Pennsylvania

regiments there was an open country with many well-tilled fields stretching away

in all directions. Towards the enemy there was a dense woods which extended to

the Marne, and known as the Bois-de-Conde. This woods was to be the scene of

some of the most strenuous fighting of the war.

French liaison officers who came back from the front to

consult with the officers of the Pennsylvania regiments declared that they had

made it almost next to impossible for the Germans to get across the Marne. Acres

of wire had been strung and machine guns had been massed at every possible

point.

Before midnight July 14, 1917, the Pennsylvania

companies were in position and although not a man had been able to secure a

minute’s sleep for over 48 hours nevertheless they were wide awake. They tried

to pierce the gloom of No-Man’s-Land, for they were anxious to get a sight of

the Hun lines. Occasionally a star shell would light up the countryside and they

would catch a glimpse of the river but none of the enemy was in sight. The flash

of a gun across the river, however, told them that the Hun was not sleeping.

Two miles back in the trenches, where their comrades

waited eagerly discussing the adventure which fell to the lost of the four

companies, envious eyes were turned in the direction of the front and they say

about in little groups talking of possibilities in the hours to come.

THE BOMBARDMENT STARTS

At 11:30 o’clock that night the very heavens were

shaken with a roar which sounded as though all the cannon in the world had

broken forth at once. The men looked up in amazement as the shells from the

French batteries in the rear went screeching over into the enemy lines. This was

something new for the Pennsylvanians for it was their first experience under

intensive artillery fire. Later they learned that this activity was designed to

break up enemy concentrations of men and munitions and to harass his artillery

concentration.

The Germans paid little attention to the French

cannonade, for the German adheres to system and the “zero hour” had not yet

arrived. Midnight came and went and the French artillery continued to hurl tons

of shrapnel and high explosive shells, to the north of the Marne.

But the hour was fast approaching when it was expected

there would be some reaction from Fritz, for it was known that he had

concentrated all his resources for a last stupendous effort. The German supreme

command was staking everything on this attempt to break through to Paris. To the

German mind such a success would mean victory and an early end to the war.

THE BATTLE OF THE MARNE

At 12:30 o’clock the German front from a distance of 65

miles belched forth a stream of fire the like of which had never been witnessed

before. It has since been described by the French as the most terrific

bombardment of the war.

It was the opening salvo announcing that the last

German offensive was on and that it was to be the mightiest of many mighty

efforts to force kultur upon the world.

The second Battle of the Marne had opened and the

allies waited nervously to learn of the result. All the free men of the earth

knew that civilization was hanging in the balance.

Documents taken from prisoners who were captured later

show that the French did not exaggerate when they declared the bombardment to be

the heaviest of the war. On one prisoner was found a copy of a general order to

the troops assuring them of victory. It informed the Germans that this was the

great offensive which was to force the Allies to make peace and that when the

time came to advance they would find themselves unopposed. The reason for this,

according to the order, was that the attack was to be preceded by artillery

preparation that would destroy completely all troops for 20 miles in front of

the German lines. It has since been learned that shells fell 25 miles back of

the allied lines.

It was the opening of this offensive that the kaiser

witnessed and Karl Rosner, his favorite correspondent, wrote to the Berlin Lokan

Anzeiger:

“The Emperor listened to the terrible orchestra of our

surprise fire attack and looked on the unparalleled picture of the projectiles

raging toward the enemy’s positions.”

Thus the lads from Pittsburg and Western Pennsylvania

also had the privilege of sharing with the then Prussian war lord all the

wonders of this “surprise fire attack.”

CROUCHED IN TRENCHES

But how were our lads in the very front line trenches

faring under the terrific hail of steel? The emperor’s correspondent described

the din as a “terrible orchestra” but most of the Western Pennsylvanians when

writing home about their experience on that night gave to it the short

four-lettered word that Sherman used.

The soldiers crouched in their trenches powerless to do

anything for themselves or each other. This most pretentious effort of the Hun

was entirely different from the low rumbling sound like thunder to which they

had become accustomed during the past few weeks. This was deafening,

ear-splitting and the earth fairly rocked under their feet. It was one

continuous roar and was heard in Paris, 50 miles away, where people resting

after their day of celebrating were awakened from the sound sleep of exhaustion

while windows cracked and pictures were jolted from the walls. And Paris heard

and wondered and breathed a prayer for the boys out there who were charged with

the mission of withstanding that avalanche of death and destruction.

The nerves of some of the Pennsylvanians were

apparently giving way under the terrible strain and there were men who had to be

forcibly restrained from rushing madly out of the trenches – anywhere to get

away from that awful noise and suspense. French and American officers went up

and down the line encouraging the men and speaking a word here and there where

needed.

The other Pittsburgers and Western Pennsylvanians back

in the support trenches two miles away fared little better than did their

comrades of the four companies in front. The Hun shells raked the back areas and

the men had to clench their fists and bit their lips to withstand the tension on

their nerves. Nevertheless, our boys fought grimly against the madness which

often comes to green troops serving for the first time under such conditions and

they were amazingly determined and courageous through it all.

A SLAUGHTER OF PRUSSIANS

The knowledge that eventually the Boche would

come forth and that they must be in condition to meet and stop him helped to

steady the nerves of many a doughboy during the seemingly long hours of that

cannonade. The artillery preparation of the Germans was for a longer time than

usual. This was because something had gone wrong with the German schedule.

The Boche is methodical and has a schedule for

everything and with this schedule goes the supreme confidence that it always

will be carried out. His schedule was upset at the very start that night by the

early bombardment of his lines and back areas. It was revealed later that after

one solid hour of artillery preparation the Germans were to swing pontoon

bridges across the Marne. This should have occurred at 1:30 o’clock. The

anticipatory fire of the French had harassed the Germans in their preparations

to such an extent that the bridges were not swung across the Marne until 3

o’clock. The original schedule also called for advance guards to be in

Montmirail at 8:30 o’clock that morning. It will be remembered that it was in

and around Montmirail that the Pittsburgh and Western Pennsylvania men were

billeted previous to moving to the northwards to support the French lines.

The German infantry advance began immediately the

pontoon bridges were across the Marne. The famous Prussian guards led. They

literally swarmed upon the bridges. The French and four companies of Americans

poured into this living mass such a rain of bullets that their rifles became hot

and their arms tired from the repeated loading and firing.

They worked fast and saw their concentrated fire tear

great gaps in the oncoming hordes, but these gaps were quickly filled by Germans

pushed forward from the rear. The Huns were herded onto these bridges like so

many cattle being driven into slaughter pens, and slaughter pens they were for

the river was soon choked with the bodies of the dead and it remained so for

several days afterwards.

Two companies of the “Fighting” Tenth boldly battle and

refuse to give way before crack Prussian divisions. When the Hun launched his

last offensive on the Marne July 15, 1917, Companies B of New Brighton and C of

Somerset were caught in the center of the rush of the Hun hordes and although

surrounded fought their way out of the gray clad masses.

WHAT THE “GREEN” TROOPS DID

Officers in describing the behavior of the Pennsylvania

boys on this memorable occasion said that immediately the Hun appeared their

nervousness and excitement dropped from them like the cloak from the body of a

gladiator just stepping into the area. Their steadiness was magnificent and they

gave assurances that they would live up to every tradition of their nation and

their state. French officers afterwards said they were amazed at the way in

which these Pennsylvanians met their baptism of fire.

It had always been the custom to have the new troops

going to France “blooded” gradually in minor engagements and in frequent contact

with the enemy before being sent into major operations. It was the intention

that the Pennsylvania troops should have this experience, but a change in the

Boche plans and the necessity for haste decreed otherwise. It was thus that

Pennsylvania troops were hurled into the greatest battle of the war without

going through the usual easy stages of approach.

The maximum German effort of the thrust was made along their front and it seemed

almost as if the enemy knew he faced green troops and by pitting against them

his crack regiments he counted on having an easy break-through. The Hun with his

perfected military machine could not understand how it would be possible for

“green” troops to withstand an attack by the Prussian guards. There was no known

rule by which such an eventuality could be even suspected, much less given the

most fleeting though or consideration. The Guards were expected to brush those

new troops aside as a man brushes a fly from off his hand – and then Paris and

victory!

THE KEYSTONE HOLDS!

Some idea of the tremendous feat accomplished by these

Pennsylvanians may be gleaned from the fact that the Germans used no less than

14 divisions – approximately 170, 000 men – in the first line on this part of

the battlefield. Behind these in support were probably 14 additional divisions.

Some of these support divisions were used to fill gaps in the front lines so

there were actually more than 170,000 Germans engaged. No figures are available

as to the French, but their lines were so thinly held that Americans had to stop

up the gaps and there were fewer than 15,000 Pennsylvanians all told in the four

regiments.

But the Keystone held. The German offensive smashed

against those living, breathing walls which could not be swayed or moved. They

were “green” troops, but the kaiser had none to withstand their withering fire

nor the cold, sharp points of their bayonets.

The Pennsylvanians wrote one of the most brilliant

pages in the military annals of the world and the story of that stand will go

down in history alongside that of the Old Guard at Waterloo, but the door to

glory and to death swung wide for many a Pittsburg and Western Pennsylvania lad

that night.

The terrible slaughter at the bridges which the Boche

had thrown across the Marne failed to stop those green-gray waves and after

sufficient of the Prussian Guards were on the south side of the river they

charged up the wooded slope. The masses were so dense that the hurricane of

machine gun and rifle bullets poured into them failed to make any appreciable

impression. They swept onward and then over the first line of trenches in which

were the companies of the old Tenth.

HAND-TO-HAND FIGHTING

The Pennsylvanians, finding themselves surrounded on

all sides, and split into little groups by the rush of the enemy, were

determined to forfeit their lives as dearly as possible. It became hand-to-hand

combat in which the Pennsylvanians were seen to rise to heroic heights. They

forgot for the moment the lessons of warfare so carefully learned in the camps,

and with bayonets and rifle butt and even with their bare hands they savagely

attacked the Huns. Men were locked breast to breast, from which the only escape

was death to one of them.

There was one lad in the melee who had his rifle

knocked from his hands and with blazing eyes and clenched fists he went at an

antagonist. The American managed to get in a hard punch on the point of his

opponent’s chin and just as he delivered the blow a bullet hit him in the back.

The German staggering under the blow on his chin threw up his arms and this

rifle dropped. The American grabbed it up and plunged the bayonet through the

breast of his enemy at the same time not forgetting to gurgle out the ferocious

“yah!” which he had learned at bayonet practice in the camps. Then he toppled

over on the German.

The little groups of Americans fought back to back and

fired and hacked and hewed at the enemy masses. No group knew how the others

were doing and many said afterwards that they felt certain that it was the end

of all things for them and that it was only a question of accounting for as many

Huns as possible before it came their turn to cross the Great Divide.

It was then that there occurred the great tragedy for

those valiant Pennsylvanians. One of their officers noticed that they were no

longer supported by the French on their flanks. Something had failed or someone

had blundered. Either the liaison service between the French and American had

been broken or the runners had been killed or perhaps an officer who had

received the orders to fall back had died before he could give the command.

ALONE IN THE BATTLE

Soon the officers and men of all four companies

realized that they were alone on the field and that the French forces had moved

backwards. It was the famous “yielding defense” of the French working, but for

some reason the Americans had not been informed of the execution of this

movement. The four companies of Pennsylvanians faced the army of the German

crown prince, but even then they were undaunted and undefeated.

No man of the four companies who went through the

Gehenna of fighting has any clear idea fixed in his mind as to just what

happened during these crucial moments. Thousands of Prussians were between them

and the French by that time and there was only one thing to do. Either die where

they were or take a chance at hacking their way through the Germans and thus

regain the lines where the French were now making a stand. This was a difficult

feat to attempt, especially when the companies were all split up into little

groups, nevertheless, it was the only way out. To have stayed and died in their

tracks would have been a useless sacrifice and civilization needed every man

that day.

The groups frequently formed fan-shaped circles and

moved backward fighting the enemy from all sides. Then one group would meet up

with another and the little forces thus combined were able to make more headway.

Company B, of the One Hundred and Tenth was surrounded and split and after hours

of fighting, during which it was necessary, time after time, to charge the Huns

with bayonets and rally the group repeatedly to keep it from disintegrating.

Capt. Fish, of New Brighton, with Lieut. Claud Smith, of New Castle, and Lieut.

Gilmore Hayman, of Berwyn, fought their way back with 123 men. They brought with

them several prisoners and carried 26 of their own wounded.

The other member of Company B were surrounded in the

woods. They made a running fight of it but were scattered badly and drifted back

to the lines in little groups. They were forced to leave many comrades behind,

dead, wounded and prisoners.

|