|

A History of Pittsburg and Western Pennsylvania Troops in the War

By John V. Hanlon (Copyright 1919 by The Pittsburg Press)

Chapter II

(The Pittsburg Press, Sunday, Jan. 12, 1919, pages 60-61)

Names in this chapter: Benz, Shenkel

PITTSBURG AND WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA SOLDIERS OF THE TWENTY-EIGHTH DIVISION IN

FRANCE RECEIVE INTENSIVE ADVANCED TRAINING AND THEN MOVE TOWARDS THE MARNE WHERE

GERMANS THREATEN TO BREAK THROUGH TO PARIS. TWO PLATOONS FROM THE OLD EIGHTEENTH

FIRST SOLDIERS OF TWENTY-EIGHTH TO PARTICIPATE IN FIGHTING. PRAISED FOR WORK BY

FRENCH COMMANDER.

When the Twenty-eighth division arrived in France our

allies were facing the most critical period of the way. All during the previous

winter and early spring the Germans had prepared for a series of drives which

they expected to break the backbone of the British and French armies before the

Americans could arrive in force.

The German expectations were heralded to the world, so confident was the enemy

high command that nothing could go wrong with the carefully worked-out plans.

The Russian fiasco had released to them many thousands of seasoned veterans and,

with these added to the armies already on the west front, the order to advance

was given March 21, 1918. Then on a 50-mile front, stretching from La Fere to

Arras, the Germans went “over the top.”

The French and British lines joined in and around St.

Quentin and the objective was to force a break and separate the forces of the

two allies. This plan did not succeed, but the enemy was able to drive a great

wedge, and Amiens, the important British distributing point, was seriously

menaced.

The second phase of the German offensive was launched

April 9 against the British in the Ypres section, and with such fury and

persistence that Marshal Haig’s troops were thrown back for a considerable

distance before they were able finally to stem the assault. But the British line

did not break and the French sent reinforcements whereby it was possible to

counter attack and regain a portion of the territory lost.

Raids and local actions then constituted the principal

activities for several weeks while the Germans were preparing for their third

effort, which began May 27 when the Crown Prince’s army was hurled forth from

Chemin des Dames, in Champagne. The allied armies were forced back until the

enemy had reached the Marne at Chateau-Thierry by June 1 and thus Paris was

directly threatened. It was at this juncture of the German offensive that

American troops were rushed to the front and so successfully helped the French

stem the oncoming hordes of the kaiser. Every American knows the story of

Chateau-Thierry and Cantigny. Here are the words of the Commander in Chief, Gen.

Pershing:

WHAT THE AMERICANS DID

“The allies faced a crisis equally as grave as that of

the Picardy offensive in March. Again every available man was placed at Marshal

Foch’s disposal, and the Third Division, which had just come from its

preliminary training in the trenches, was hurried to the Marne. Its motorized

machine-gun battalion preceded the other units and successfully held the

bridgehead at the Marne, opposite Chateau-Thierry. The Second Division, in

reserve near Montdidier, was sent by motor trucks and other available transport

to check the progress of the enemy toward Paris. The division attacked and

retook the town and railroad station at Bouresches and sturdily held its ground

against the enemy’s best guard divisions.

“In the battle of Belleau Wood, which followed, our men

proved their superiority and gained a strong tactical position, with far greater

loss to the enemy than ourselves. On July 1, before the Second was relieved, it

captured the village of Vaux with most splendid precision.”

Thus the enemy began to secure demonstration of the

fighting ability of the Americans, and to meet lines of adamant that would

neither bend nor break. The enemy was stopped at the Marne, but one week later

another offensive between Montdidier and Novon in a new thrust for Paris. The

allied supreme command had advance information and this blow was readily

checked. This was the situation during the last days of June, the darkest hour

of the allied cause when it was feared that Paris was doomed and such a

catastrophe would literally take the heart out of the French.

It was during these stirring times in June that the

Pittsburg and Western Pennsylvania infantrymen were billeted within sight of

Paris and hearing of the wonderful work of their countrymen who were privileged

to be taking part in the mighty struggle. They heard of Chateau-Thierry, Bois de

Belleau, Bouresches, Cantigny, those milestones already recorded in the history

of the American arms and they fretted and strained at the leash which held them

far from where there were deeds of valor to be performed and glory to be won.

BRIGADED WITH THE BRITISH

When the division arrived in France it was split up

into small units and brigaded with the British troops to receive its final

instruction before going to the front. At times the men became discouraged as

the result of what they deemed an exceptionally long training period for they

felt fit to meet any Boche that ever lived. Some of the men even began to wonder

if they were to see any of the real fighting.

The supreme command had worked out a special system for

training new troops whereby they were gradually brought to the state of

steadiness and perfection required for the line by a series of movements ever

nearer the front and thus closer and closer to the sound of the guns. Then the

men moved up within the actual zone of artillery fire where through experience

gained at times as the result of casualties, their nerves were steeled to

withstand the din of battle.

Next there was a period in the front line under the

watchful eye of experienced officers. But the Americans “made good.”

During the course of training with the British the

Pittsburg and Western Pennsylvania troops were stationed near Lumbres and later

at the French training centers of Ge[unreadable} Maux and Rebais.

The Division was partly reassembled a few miles

northwest of Paris with headquarters at Gonesse. This town is about ten miles

from the heart of the French capital. The four infantry regiments together with

the engineers were scattered throughout the surrounding towns and countryside

wherever billets were available.

UNITS ARE SEPARATED

At the time of arrival in France the artillery brigade

of the division, which included the One Hundred and Seventh regiment, was

separated from the other units and sent to an artillery training camp many miles

away. Other units had been sent to other places for specialized training. The

infantry and engineer regiments assembled first and then awaited the arrival of

other units at the divisional center and it was during this wait that the

Pennsylvania doughboys began to long for a nearer approach to that direction

from which ever came the low rumbling sound like continuous thunder. To the

southeast on clear days they could see the great Eiffel Tower in Paris.

But the men did not get much time to ponder over the

reasons for the delay in keeping them out of the conflict. They were busy those

warm June days in going through that maze of work incidental to their final

graduation from the school of the soldier. It was a trying period but it was

soon forgotten in the days which followed.

The Germans were preparing for another thrust at the

Marne. The bald, naked truth is that the British and French were fearful that

they did not have sufficient men to stop the Hun. Even during the last rush the

lines were but thinly held and would probably have given away had not the few

American troops which were ready been rushed up in the night in motor trucks and

thrown into battle.

An appeal had gone forth for more Americans and casting

aside all thoughts of a distinct American Army for the time being Gen. Pershing

offered all the troops available to be brigaded with the French and British

armies in a supreme effort to save a world.

The American Army at that time was merely an army on

paper because it had not been assembled. Divisions were the largest units then

working as a whole and by brigading these divisions with the British and French

the gaps would be stopped up and their forces strengthened by all the available

American forces. Their army units were functioning with the experience of the

long years of war and it was an easy task to assimilate the American divisions.

Time was short, too, in which to work effectively.

It was at this juncture in the fortunes of our allies

that the order came down the line for the Twenty-eighth Division to prepare for

a journey. The artillery brigade had not yet come up to join the division so the

infantry and engineers were to go away without it.

When the time came to depart for their new destination

the men noticed that long lines of motor trucks awaited them and there was much

jubilation, for here indeed was evidence of a respite from the wearisome hikes.

They were to ride in state for the motor trucks looked to them like the best to

be had in the way of transportation.

There was expectancy in the very air for to be accorded

the luxury of a motor ride was unusual up to that time for the men of the

Twenty-eighth. However, they were disappointed when the direction taken was not

to the northeastward nor to the northward from whence came that rumbling sound,

but eastward from Paris. They journeyed on through petty French villages where

the townspeople greeted them as saviors when they discovered they were

Americans. The Pennsylvanians sang and cheered until they were hoarse. Soon they

came to a little river, the Petit Morin, and down along it beautiful winding

valley the great trucks lumbered carrying their happy and cheerful burdens.

Suddenly the men discovered that the distant thunder

was gradually getting louder and they commenced to realize that they were

approaching that zone where the guns were continuously belching forth their

messengers of death. They knew, too, from the people along the way that they

were nearer the battle lines and then finally they stopped in a little town

beside the river.

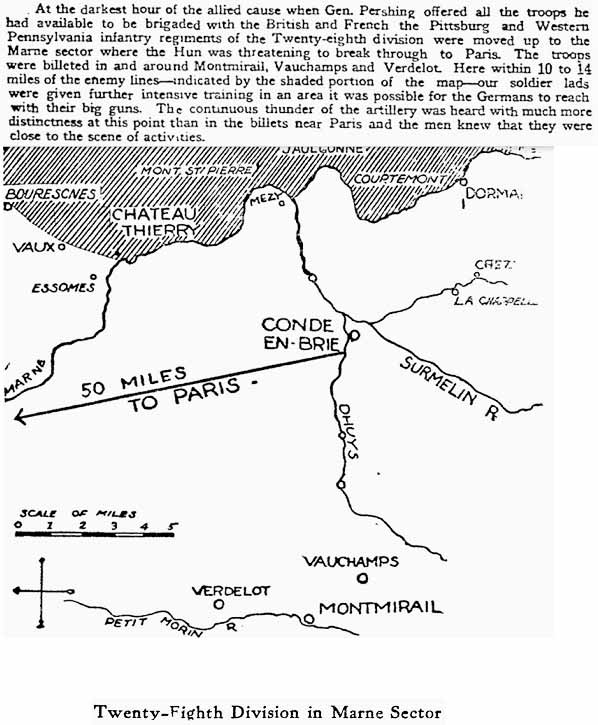

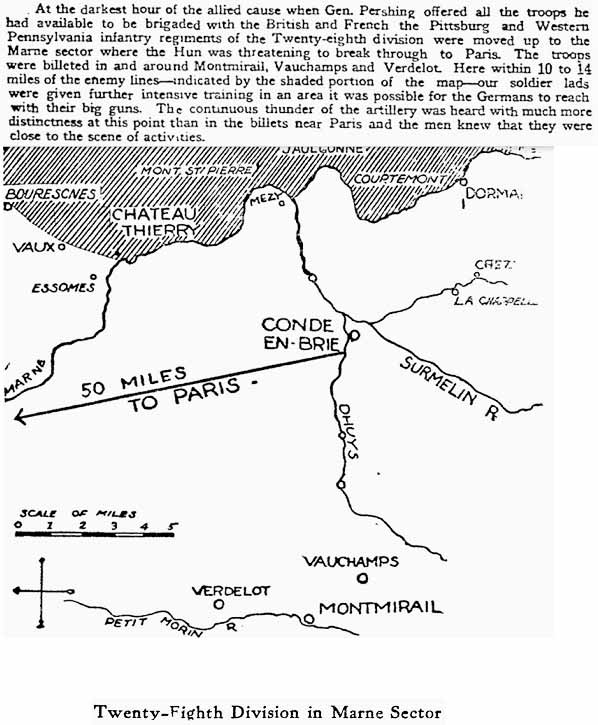

AT MONTMIRAIL

This town was Montmirail and the distant guns could be

heard distinctly. Part of the division passed through Montmirail and stopped at

another town a few miles to the eastward. This town was Vauchamps. The rear of

the column turned off and stopped at Verdelot, to the westward a few miles from

Montmirail. The surrounding countryside was dotted with villages and in the

three towns and these villages the local doughboys and engineers billeted.

The pause here was but another step in the advanced

training of the men so that they could become more familiar with the sound of

the guns and it was only a few days before they ceased to notice that ever

rising and falling rumble which made the earth tremble under foot even at that

distance.

Now the soldiers from Pitts burg and Western

Pennsylvania began to glow serious and to buckle down to their training work

with even more determination to approach nearer perfection for they realized

that the day would soon come when they would have an opportunity to let the

folks at home and the world knew that the men of the Twenty-eighth were not

afraid of anything the Hun had to offer.

Within a few days they commenced to grow restless,

however, because they had not moved nearer to the guns so that they might at

least obtain a distant view of more of the activities which were going on to the

north of them; activities amongst the most important in the long was and Paris

as the stake. They were not more than from 10 to 14 miles from the front lines

along the Marne and could not understand why they were not up there helping the

French to hold back the enemy from any further advances.

This was the situation as it pertained to the Pittsburgh and Western

Pennsylvania regiments during these last days in June. Little did the men dream

that before the end of another month they would have decisively demonstrated

their mastery of the pick of the Prussian soldiery and had writ large on the

pages of history that story of valor and achievement which sent a thrill

throughout America and the kaiser reeling with disappointment and chagrin.

And little did they realize that there were many there

in those last days who would never be with them again; many who would be found,

after the tide of battle passed, with cold set features and with the light gone

from their eyes, the victims of the Hun; others cruelly shattered in mind and

body and facing a lifetime of helplessness and misery.

But even if these soldiers from Pittsburg and Western

Pennsylvania could have known in advance the bloody days directly ahead of them

they would not have been less keen for the carnage: to have known would have

only whetted their desire to rise to even greater heights of bravery and daring

if such were possible. There were folks at home who in other days had spoken of

the guardsmen as “tin” soldiers. And there were officers of the regular military

establishment who had scoffed at them and questioned their usefulness in a

crisis. Both these insults were to be wiped out forever; wiped out in such a sea

of blood by men who were to prove themselves the peers of any men-at-arms the

world had ever known that a blush of shame would mount to the cheek of every

person who ever uttered an unkind remark against the old N.P.G.

ON THE FOURTH OF JULY

Came July 1, 1917, and the Pittsburg and Western

Pennsylvania boys were still billeted in and around the vicinity of Montmirail,

from 10 to 14 miles from the front lines on the Marne. They were planning for

some sort of celebration for the Fourth in order to help while away the tedious

hours of waiting for a shot at a Boche. Something extra in the way of food was

to be topped off with concerts, sports, etc., was on the program. There was some

comfort in the prospect of getting away from the tiresome and heavy routine,

too, because they expected to be allowed to rest at least part of Independence

Day.

Midnight, Wednesday, July 3, 1917, there was a stir in

camp when the One Hundred and Ninth Regiment, from Philadelphia and the eastern

part of the state, was routed out and formed into companies in heavy marching

order. Here at last was a prospect of action! Wild rumors flew up and down the

line to the effect that the Hun had broken through and that the Pennsylvanians

were going out to stop him. Some of the Pittsburgers and Western Pennsylvanians

in the One Hundred and Tenth, One Hundred and Eleventh and One Hundred and

Twelfth Regiments heard of the sudden movement and were wondering why it had not

been their luck to be called.

The night rang with the hastily snapped out commands as officers prepared the

regiments to move forward. Then when the order to march at double time was given

the men were sure that something was happening. It was a long weary hike with

the sound of the guns ever getting closer and then just before dawn the head of

the column was stopped by a staff officer who arrived in the sidecar of a

motorcycle and Col. Millard D. Brown, of Philadelphia, in command of the

regiment, was ordered to return to billets.

This was disappointment indeed and when the order for a

short rest was given the men just dropped down in their tracks, equipment and

all. They were dead tired after that long hurried journey, but while there were

prospects of real work to do they were willing to bear without flinching the

rigors of that wearisome march in the dark.

The night had been cool, but when they were ready to

trudge back towards their billets the sun was well up and beating down in all

its July fury upon their heads. They thought of the celebration they had missed

back in camp and they wondered what the loved ones back in American were doing

to while away the holiday.

CHUCKLES OVER “FALSE ALARM”

It was night before all the companies were finally back

in camp and so all thought of any Fourth festivities was gone. They were mighty

glad to crawl into bed. As to the celebration conducted by the other regiments,

it is said by officers, that, when it became generally known that the One

Hundred and Ninth had gone forward in the night, the men considered themselves

so out of luck that they didn’t care whether they extracted any joy out of the

Fourth’s festivities or not. However, the men of the other regiments surely did

chuckle the next day when they learned of what the One Hundred and Ninth has

been through.

But during this period the Pennsylvanians were wondering as to the experiences

of certain of their number who were on the front line receiving some advanced

instruction under the French. Several platoons had been picked from the Division

and sent in with the French just west of Chateau-Thierry. This sector was not a

quiet one, neither was it real active just at that time.

Two of these platoons were from the old Eighteenth and

were under the command of Lieuts. Cedric H. Benz of Co. B and John H. Shenkel,

of Co. A, both of Pittsburg. Then the sector in which they were stationed

commenced to grow hotter as each hour passed and July 1 the French decided to

launch attacks against the village of Vaux and Hill 204, nearby.

The Americans carefully watched the French go about the

preparations for this attack, with that skill which is only obtained after long

and arduous campaigning. The Americans were invited to take positions where they

could easily view the whole operation. The platoons from Pittsburg had made such

an impression on the French that the French commander informed them they might

participate in the attack if they so desired, but that such action would be

entirely voluntary. Those who elected to go were invited to step out of the

ranks and every man of the two platoons came forward with a snap that

demonstrated how eager they were to get into some actual fighting.

They went into the battle with the French and under

French command and they were the first troops of this division to engage in

important fighting.

Here is the story of that attack told by the French

general commanding:

AMERICANS ROUT THE ENEMY

“On the morning of July 1 a platoon of the One Hundred

and Eleventh Infantry in command of Lieut. Shenkel participated with several

platoons of French infantry in the attack on Hill 204. The battle opened with

sharp machine gun fire from the German forces, concealed in trees, underbrush

and trenches. Immediately on gaining the heights of Hill 204, Lieut. Shenkel

deployed his troops to the right and left of him for the purpose of making flank

movements.

“As the Pittsburgers and the French commences to close

in on the German troops an avalanche of machine gun fire greeted them. The

soldiers refused to give ground and continued their advance. Seeing that the

machine gun fire could not check the advance, the German officer in command

called for a barrage fire, but before this could be laid down the Americans had

routed the enemy from his first line of trenches.”

Lieut. Benz went in on the left of Hill 204 with his

platoon and together with the French completely routed the German forces. He

succeeded in bringing 38 prisoners back to his lines.

The French general in his report on the work of Lieut.

Benz said:

“Lieut. Benz and his platoon of American and French

soldiers, in spite of the firing of the enemy’s heavy and light machine guns,

trench mortars, riflemen placed in trees, bravely threw themselves on the

adversaries in a fierce hand-to-hand contest, in a thick and almost impregnable

woods, not only routing the German forces but taking 38 prisoners back to his

lines.”

The sector where Lieut. Benz operated was of the utmost

importance. The enemy had concentrated large forces and a menacing shrapnel fire

was continually harassing our troops located at Vaux directly within the range.

The lieutenant and his men started towards the crest of the hill. They soon

gained its heights and were forcing their way through the heavy underbrush when

a burst of machine gun bullets was sprayed on them.

FOUGHT LIKE DEMONS

Taking positions as skirmishers the men pressed forward

even under this heavy fire while the enemy troops quickly retired to the second

line trenches. The lieutenant saw a chance for a rush before the enemy could set

up his machine guns in the new position and his men were quickly upon them,

forcing them back to the third line and then finally out of the woods.

It was then that a number of the Germans became

panic-stricken and beat a hasty retreat, leaving Benz with his 38 prisoners.

Lieut. Shenkel was also busy on the other side of the

hill during all this, for by a flanking movement a detachment of German soldiers

had succeeded in trapping Shenkel and a squad of his men, but this was quickly

broken up by a counter-attack. The lieutenant and his seven men fought like

veritable demons, cutting and hacking their way through the Germans with

bayonets and the butts of their rifles. Lieut. Shenkel flirted with death more

than once that day for three times he was [unreadable] by a German sniper who

was concealed in a tree. Each time the bullet pierced part of his uniform.

In commending Lieut. Shenkel for his part in this

battle the French high command after telling of his ardor and bravery in the

taking of the hill declared that “the American people should be proud of the

wonderful soldiers that are now fighting with the allies.”

“The odds were ten to one against you,” said the

general, “but the great disadvantage did not dampen the ardor and bravery of

your men. You troops today did what I thought was impossible. You have taken a

position which is of the upmost importance.”

Thus with the taking of Hill 204 one of the most

important gains of the Marne sector was made. The Germans prior to the

engagement with the French and Americans concentrated more that 1,000 soldiers

and an exceptionally large amount of ammunition. They were preparing for an

attack on Vaux which had been previously wrested from their grasp by the

Marines. Had not the Pittsburgers taken Hill 204 the Germans would have had a

commanding position whereby they could have readily shelled the Americans out of

the town.

The battle opened at 6 a.m., July 1, and raged all that

day but before the dawn of the next day there was not a Boche remaining on Hill

204.

AIRPLANES BOMBING GERMAN TRANSPORT WAGONS

The work of airplanes in attacking, at low

altitudes, the ammunition transport wagons of the enemy has been very successful

in cutting off huge quantities of supplies for the front lines.

GLORY FOR THE OLD EIGHTEENTH

Both the Pittsburg lieutenants were cited by the French

for their part in this glorious victory and both received the coveted croix de

guerre. In speaking later of the work of the men who were in his platoon, Lieut.

Shenkel said that the boys showed wonderful courage and ability and that the

people of Pittsburg and Pennsylvania should be proud of every one of them.

Lieut. Benz says that too much credit cannot be given boys of the old Eighteenth

for the wonderful work they did in chasing the Boche from Hill 204.

Before many hours had passed news of this action had

filtered back to the regiment and also stories of the wonderful work of their

comrades, with the result that each man pledge himself, in his own hand to live

up to the standards established by the men of the two platoons from Pittsburg.

Now more than ever before were the men chafing under the restraint which had

them back from the front lines, for they were absolutely confident that they

could outfight any Boche that ever lived.

But the regiments kept up that deadly routine of drill, bayonet work and rifle

practice, together with frequent hikes and all the other activities of intensive

training. The men at times began to feel they were “going stale” from

overtraining, but the real trouble was their anxiety to get into action.

|