Disease and Urban Image: Yellow Fever in Norfolk, 1855.

On the Yellow Fever of Norfolk & Portsmouth

"SADNESS TO OUR CIRCLE":

Grace Whittle's Account

of the 1855 Norfolk Yellow Fever Epidemic

Edited by Jennifer Davis McDaid, 1997,

Archives Research Coordinator,

The Library of VirginiaReproduced with the permission of the author and the Library of Virginia.

While vacationing in Pinopolis, South Carolina in October 1859, Grace Latimer Whittle commented on a common annoyance to travelers in the American South: mosquitoes. In a postscript to one of her father's letters, Grace reported to her aunts in Philadelphia that she had seen only one of the pesky insects and heard two more from her vantage point on Lake Moultrie. "I am sure," she wrote with confidence, "you must give me credit for being an accurate historian, at least on this subject." Four years after witnessing Norfolk's yellow fever epidemic, Grace remained wary of warm weather and relieved to see autumn's first frost. According to popular belief (and, to a certain extent, medical fact), this drop in temperature signified the end of the dangerous summer season of disease.1

In her journal, Grace penned a vivid report of the 1855 epidemic and its effects. Born on 29 August 1831 to affluent parents (her father a lawyer and businessman, her mother the daughter of a judge), Grace led an average, if undeniably privileged, life. She attended school somewhere in Norfolk, along with her sisters; married Horace H. Sams on 18 October 1860; and afterwards moved from her parents' house to a South Carolina plantation. After her husband died of typhoid fever on 22 May 1865, Grace and her two young children returned to the Whittle home in Norfolk, where she lived until her death on 15 December 1897. A brief burial notice identified Grace Whittle Sams with customary anonymity as her father's daughter and her husband's widow. No known portrait of her has survived. Her account of the yellow fever epidemic, written in a small lined book purchased from a local stationery store, is evidently the only journal volume that Grace left behind.

Yellow fever descended rapidly on Norfolk and Portsmouth after the steamer Ben Franklin came into port in June 1855 from the Virgin Islands with an ailing crew. Before the Board of Health discovered that the ship's captain was concealing sailors infected with the fever, workers at Portsmouth's Gosport Navy Yard had fallen ill. They, in turn, carried the disease home on the ferry across the Elizabeth River to Barry's Row, a Norfolk tenement at the southern end of Church Street. Meanwhile, aided by standing water in barrels, lanes, and buckets, infected mosquitoes bred. Early in August, the Richmond newspaper reported the first deaths, while the Norfolk press fell silent as editors and staff were stricken. Before the fever waned in October, 1,800 inhabitants of Norfolk (nearly one-third of the total population) had died.2

Yellow fever was not an unfamiliar malady to the residents of Norfolk. As a densely-populated seaport city, it was particularly vulnerable to the disease, which was nearly always fatal. It was not until the turn of the century that scientific research linked the Aedes aegypti mosquito with the transmission of yellow fever. The heat of the humid summer months, along with the city's constant problem of standing water, was instead routinely blamed for outbreaks of illness. While the causes of yellow fever were not readily apparent, its symptoms were dramatically evident. Victims experienced a sudden onset of chills, muscular pain, and jaundice, followed by massive internal hemorrhaging. In most cases, patients suffered delirium and convulsions before dying from damage to the liver, kidneys, heart, and blood vessels.3

The medical remedies of the mid-nineteenth century did nothing to slow the course of the disease and did little to ease patients' suffering. An 1853 reference text, The Art of Medicine Simplified . . . for the Use of Families and Travelers, advocated large doses of calomel (a purgative) internally and the liberal application of a mercury-based ointment externally. In the case of total collapse, a sniff of ammonia and a shot of brandy were recommended. In the city's streets, barrels of tar were burned to dispense with harmful germs; inside houses, women mixed a potion called "thieves vinegar," a powerful disinfectant used in sick rooms. Despite the abundance of advice available, doctors and nurses could ultimately do little to cure or comfort yellow fever patients. Unable to heal the sick, they disposed of the dead in a city where proper and sanitary burial was no easy task. A shortage of coffins and grave diggers (and the increasing number of corpses, many unidentified) made this duty a trying one. In the face of such rapidly declining public health, residents who were able fled the city. By the end of the summer, thousands of individuals had abandoned their homes and businesses for healthier surroundings.4

Many of the city's inhabitants did not have the resources or opportunity to flee the fever. The poor, recent immigrants, and slaves were the hardest hit by the devastating effects of the epidemic. In a futile attempt to contain the spread of the disease, Norfolk city officials evicted the remaining residents of Barry's Row (largely shipyard workers) and built a fence around the neighborhood in late July. The five-member Board of Health exiled the ailing tenants and their families, carting them to a hastily-established hospital outside the city limits at Oak Grove. These measures did little to alleviate the unhealthy environment of the buildings, which had been built on poorly-filled marsh land. Inspectors later testified that moisture seeped into the basements of Barry's Row, where it puddled and stagnated. Additional problems were caused by the unpalatable well water in that section of town, which prompted residents to use rainwater collected in thirty-year-old underground cisterns for drinking and washing. Under these conditions, it was no wonder that the epidemic flourished. Grace's father Conway Whittle reported in a letter to his sisters that he had heard "some very loud whispers" concerning a plan to set fire to the abandoned row of dilapidated buildings; on the night of 13 August, a group of citizens gathered and torched the twelve tenements, while city firemen protected nearby buildings from damage. While the objectionable buildings were adequately insured against fire, the Mutual Assurance Society in Richmond refused to compensate their owner, James Barry, since their destruction had been openly "permitted and countenanced for the public safety."5

Grace Whittle watched the flames consume Barry's Row from the front door of her parents' home. Joining her was Reverend William Jackson, pastor at nearby St. Paul's Church. Grace's diary records the hope voiced by Jackson and shared by the city that the fire would rid Norfolk of any remaining infection. This, of course, was not the case. Jackson had already presided at the first of many funerals, that of Imogene Barron, wife of the naval commander at Gosport. While her husband Samuel and daughter Elizabeth lay ill, Barron's body was transported from Portsmouth at night and interred in Norfolk. The fire that ravaged Barry's Row would not bring an end to such grim duties. Grace noted that the disease appeared only to gain strength as the intense heat of the summer increased.6

Like their counterparts in Norfolk, the poor and the immigrants were the first to fall ill in Portsmouth. The crowded conditions of the tenements (given the derogatory label "Irish Row"), along with poor diet, unquestionably fostered the rapid spread of fever. Episcopal minister James Chisolm of St. John's Church, in Portsmouth, recorded the desperate straits in which these lodgers found themselves. With little (if any) Christian charity, Chisolm reported the unwillingness of the sick to leave their homes. As in Norfolk, city officials were determined to remove "the wretched and squalid patients" to a pest-house conveniently located on the edge of the city, near the cemetery. Chisolm indignantly noted that the sick and their families "refuse[d] to stir." In the end, nine cartloads of "these unfortunates" were hauled away under considerable protest. Chisolm's distaste for these poor and predominantly Catholic citizens is evident in his account of their removal. Such ethnic, religious, and class prejudices, highlighted in the fear that accompanied the outbreak of the fever and the name-calling that resulted, seemed to wane considerably as the epidemic progressed. As conditions worsened, ministers, nuns, and priests alike attended to the physical needs of the sick with no regard to their denomination.7

While the poor segment of the population seemed at the mercy of the frightened upper classes, the black population of Norfolk was virtually ignored. In 1850, thirty percent of Norfolk's population was composed of slaves. The Whittle family owned two young female slaves (ages twenty-three and fourteen) at the time of the epidemic. Before the family left town, Grace's mother Cloe made some sort of "satisfactory arrangement" for them, evidently providing for their food and housing. Most were not so fortunate. The situation of slaves, Grace observed, was "very trying . . . [for] they saw their owners flying from the pestilence which they were left to encounter . . . with inadequate provision for their support during the Summer."8 Some Norfolk families left in such haste that their slaves were left without the essentials in a city where businesses and markets were closing and the port was under quarantine restrictions. Norfolk resident Anne P. B. Herron lamented in a letter to the Whittle aunts that "masters and mistresses . . . [had] deserted faithful servants without leaving them the means of subsistence in health, or aught to solace them in sickness."9

Many owners firmly believed that their slaves possessed a genetic immunity to yellow fever; as a result, it was rumored that they would take advantage of the dire situation and rebel against the weakened and vulnerable residents of Norfolk. Such an alleged slave plot had caused New Orleans officials to place armed patrols on their streets in June 1853, when yellow fever was reaching epidemic proportions there. While even Grace heard the rumors of revolt (although her father tried to shield her from such talk), nothing came of them. Slaves as well as their owners fell ill and died. Those blacks who remained healthy were often pressed into service as grave diggers, hearse drivers, and even as nurses.10

The epidemic rapidly put an end to the order of everyday life, wreaking havoc on the economy and society of Norfolk while creating a vast gap in the public record. Newspapers ceased publication, vital statistics were only randomly kept, and the Norfolk city council disbanded. Telegraph reports to Richmond were the only means of communicating the dire circumstances which had befallen the city. Downtown businesses closed and the port was quarantined, leaving items necessary to nursing (such as foodstuffs, linens, and medicine) in short supply.11

The Whittle family remained in beleaguered Norfolk longer than most families of their means. While the city itself was quarantined, many socially prominent and economically privileged inhabitants beat a hasty path westward to the salubrious Virginia springs, or traveled north to visit family and friends. Conway Whittle could have easily packed up his wife and daughters and fled to Philadelphia, where his sisters lived. Mary W. Neale and Frances M. Lewis had in fact written to their brother urging the family to come while they were still able; Conway replied at the beginning of August (when the epidemic was escalating) that the Whittles would not leave unless events took "a still more unfavorable turn." Conway also resisted the arguments of his brother-in-law, William Armstrong, who was preparing to leave with his wife Adelaide and their children on a hired steamer. Armstrong's fear of the yellow fever was understandable; during a scarlet fever outbreak in 1841, the family had lost three children (ages four, six, and nine) to the disease in three weeks time.12

Conway's stubbornness left his twenty-three-year-old daughter in Norfolk long enough to observe the fever first-hand. She recorded her impressions of the epidemic in a journal, written some time during or after her family's departure from the city. While she prided herself on being "an accurate historian," her account of the fever's progression keenly related the personal as well as the physical impact of the summer's grim events. Especially poignant to Grace was her last visit to St. Paul's Church, where she taught Sunday school. Although she and the other teachers confessed to "mutual fear and anxiety," Grace tried to impress on her solitary student that hope, not despair, would give "peace to the mind under such circumstances." Such advice, however uplifting, could only dull the pain she herself felt on the loss of friends and acquaintances. Those who died from the fever are carefully underlined in her journal. While other women experienced the epidemic, Grace recorded it, using the objectivity and detachment of a historian to preserve her memories of the summer of 1855. The Whittle family finally left their home in late August, traveling up the peninsula to Newport News and Petersburg, then turning west to Charlottesville, Rockbridge County, and the springs of Bath and Greenbrier counties. They returned to Norfolk in mid-November, when frost had finally eliminated the danger of infection.13

In search of relief from the heat of the city, fifty-seven-year-old Mary Thompson had taken "cool and quiet rooms" at Old Point Comfort's Hygeia Hotel early in the summer. Since Thompson's husband William was a "steamboat proprietor," she was most likely able to leave the city with relative ease. A family friend and regular correspondent of Grace's aunts, Thompson reported with satisfaction that there was "not a mosquitoe" present at the Point. By the beginning of August, however, Thompson found herself under quarantine at the hotel and hard-pressed for paper, stamps, and other necessities. Her letters recorded her increasing despair, heightened by the illness and death of her friend Imogene Barron. Barron's fourteen-year-old daughter Lizzie also succumbed to the fever while her father, Samuel Barron, grew exhausted and severely depressed. The Barron's youngest child—still breastfeeding when taken from its ailing mother—fell ill with whooping cough. Thompson's regular letters to Philadelphia lapsed after relating these traumatic events. When they resumed a week later from Fauquier Springs, she admitted that she had been so shaken by the loss of "those most beloved ones at home" that she was unable to pick up her pen and write.14

Unlike her friend Mary Thompson, Anne Herron remained in her downtown home throughout the summer. A fifty-one-year-old native of Ireland, Herron nursed her brother through a mild case of the fever and kept a watchful eye on her twenty slaves. Writing to Grace's aunts in late August, Herron lamented that she was unable to offer "one cheering word" in light of the desolation that surrounded her. Of special "concern to Herron were the slaves who had been left behind in Norfolk by their owners with few supplies and resources. While the Whittle family made provisions for their two slaves, most were not so fortunate. Herron herself had seen some "heart-rending cases," where slaves had died destitute and "without a friend by hand to offer one comfort." Herron's brother and some of her friends tried to dissuade her from staying, encouraging her instead to "seek a place of safety." Arguing that self-preservation was of little importance when it destroyed "every feeling of humanity," she sharply questioned her critics: "Is this Christianity? What would we think if our servants were to abandon us? Is this justice?" Herron nursed seven of her slaves through the fever. By the end of September, she was dead.15

Women's usual concerns for the well-being of the family were heightened as the course of the fever progressed. With ten children and thirteen slaves, Elizabeth Whittle felt that God expected her to act as their caretaker. The wife of Grace's cousin William C. Whittle, Elizabeth wrote to Philadelphia for emotional support. "All Mothers," she commented, "require this cheering approval." Despite the distinct disapproval of her brothers, Elizabeth and her children remained in Norfolk. Her responsibility to her slaves, she argued, extended to them in sickness as well as health. After explaining her actions to the Whittle aunts, Elizabeth worried that her note would be "scarcely intelligible":but could you see the numbers of little ones around me—petting my arm and asking questions you would wonder that I can write at all—But I send you the best I can under the circumstances—I have no envelopes and there is not one store open in Norfolk.

She fashioned a makeshift envelope and mailed her letter. Two weeks later, both she and her eldest son Arthur had fallen victim to the fever. Two younger children were stricken, but recovered.16

Tested by disaster, these women reached out to each other for support and guidance. Within the network of family, concerns were voiced and comfort given. Both Elizabeth Whittle and Anne Herron stayed in plague-stricken Norfolk against the wishes of some family members and friends. Their behavior, however, was not so much a disregard for social norms as it was a reaction to extraordinary circumstances. With their physical community crumbling around them, these women fought to maintain their remaining ties to the inter-related communities of church and family. Concern for their slaves, as members of the household community, was an extension of this effort to exert a modicum of control over the chaos surrounding them. While a sense of Christian responsibility motivated Elizabeth Whittle to stay in the city, Anne Herron remained because it was against her personal principles of morality to leave those in need behind. Those women who fled—often at the insistence of fathers and husbands—attempted to maintain community ties through regular correspondence relating everyday events to those left behind.

Six months after their return, life had taken on a semblance of order for those women who survived the fever. As Mary Thompson reported to Philadelphia, however, all was not entirely well with her. As she had been in the midst of the epidemic, Thompson was plagued in the early months of 1856 by "an uncommonly obstinate fit of dislike for pens and paper." When she did write, it was to describe the "wonderful spiritual manifestations" that were occurring daily at William Whittle's home in Norfolk. Whittle's thirteen-year-old daughter Sally had reportedly become a writing medium, receiving messages from her late mother and brother from beyond the grave. Skeptical of these communications even though the penmanship was exactly like that of that of the deceased, Thompson grudgingly admitted that there was a supernatural agency at work somewhere. Whether it was good or bad was another matter entirely.17

Elizabeth Whittle, her son Arthur, and their minister William Jackson all professed through Sally to be "happy and in Heaven." Captain Samuel Barron, now recovered, had received similar communications from the spirits of his late wife and daughter. While Thompson staunchly maintained that the Bible was the only "rule of life," she too garnered some comfort from these messages from those lost so suddenly. From the advent of American spiritualism in 1848, its practitioners and advocates had argued that such "wonders" strengthened spiritual beliefs with physical facts. The world of the spirits was, after all, just as real as the material world, as reciprocal communications between the living and the dead (such as spirit writing, rappings, and table tipping) demonstrated. To those mourning friends and relatives, spiritualism offered the comforting conclusion that the soul was immortal. 18

Such comfort was an understandable craving for women who had witnessed the disruption of their entire fabric of life during the summer of 1855. Grace Whittle heard one evening in August that bodies were piling up in Norfolk's potter's field with no one to bury them, and nothing to bury them in; Mary Thompson reported shortly afterwards that a friend, Helen Wilson, had been laid to rest in a dry-goods box with no one but the driver of the hearse to mourn her. Other victims were left "uncoffined" by their families in the Catholic churchyard in Portsmouth, in the hope that they would be interred in consecrated ground. Death, while an undeniable part of life, was nevertheless hard to bear when it came so suddenly and indiscriminately. A reporter for the Richmond Enquirer admitted that the fever did not play favorites and "was confined to no particular locality or class of citizens, all being alike sick and dying." Those who witnessed the epidemic were haunted by its physical horrors and sheer magnitude. A year later, the city was still struggling to recover from what the Common Council called "the blasting effects of the late epidemic." "Houses are tenantless," the members reported candidly in August 1856, "labor is not at demand and the prices of the necessities of life are so high that the greater part of our citizens must find it hard work to keep from debt."19

Racked with fever, victims were often oblivious to their surroundings and unable to communicate their fears and farewells. The death of young Lizzie Barron (at Mary Thompson's abandoned house, separated from her still-healthy siblings) was especially terrible; for twelve hours before she lapsed into a final coma, she screamed in pain "with scarcely any intermission." Elizabeth Whittle was insensible to the fact that her children, including a nursing infant, had been taken away from her for their safety. Anne Herron remained conscious, but was unable to speak during the fourteen hours preceding her death. With such painful and abrupt partings, it was no wonder that Sally Whittle's spirit-writing was embraced as a comfort by those who remained.20

In the face of omnipresent illness and death, these physical and spiritual struggles to hold community and family together undoubtedly took their toll. The faith of women like Grace Whittle was shaken by events which prompted questions, however quiet, about the existence of a loving God. Grace's exposure to the ravages of the epidemic, and the death of her husband in the Civil War ten years later, evidently combined to change her spiritual outlook from one of active hope to one of passive acceptance. A devoted Sunday school teacher in her youth, in middle age Grace had to be prompted by her younger sister Cloe to take her children to church more often. For Grace Whittle and countless other women, the yellow fever epidemic sparked a crisis of faith. Less economically fortunate women struggled on a more basic level to survive in the face of severe deprivation. For some it undoubtedly seemed like the end of the world.21

Like most nineteenth-century women, Grace Whittle cast only the faintest shadow on the historic record. Even among the Whittle family papers, Grace's measured handwriting appears in only one slim journal volume, while that of her sister Cloe (a prolific diarist) fills sixty. Grace Whittle's account of the yellow fever epidemic, however, is a unique document which allows historians to begin two important tasks. Over 140 years after the event, the diary itself provides an extremely personal and detailed account of a period of time, in large part, previously lost. While the diary increases our understanding of the summer of 1855, it also (and perhaps more importantly) enhances our knowledge of one woman's life. Describing a house abandoned by its owners during the fever, Grace was reminded of "the State of Pompeii when first discovered" by archaeologists, with its contents telling a riveting story to the careful observer. She would undoubtedly be surprised that the diary she filled with an account of family life serves a similar purpose for researchers today.* * * * * *

An account of the Summer of 1855 being the year that our City was so severely visited by the yellow fever 22

Late in June the Steamer Ben Franklin came into the harbor, and was received at the Navy Yard in Gosport; without any notice being taken of the fact that several of the crew had recently died of the yellow fever, the steamer having just come in from the West Indies.23 Many of the workmen at the Yard were taken sick and there were some deaths, the first among our acquaintances was that of Mrs. Barren the wife of the captain on that station.24 Whose remains were brought over the river, a few hours after her death and interred at night by the Rev Mr. Jackson.25 There were now several cases in Norfolk but all were confined to the lower part of the City, and principally to a number of small buildings called Barry's Row, these were set on fire26 the night after Mrs B's funeral when Mr J was spending the evening with us, we went to the front door to see the flames and Mr J expressed the hope that the fever would be stopped by the destruction of these buildings, but this was far from being the case as the disease appeared to gain strength from that time. We now heard continually of persons having left town Sometime the big boats would carry as many as four or five hundred at once far more than they could accommodate. These accounts coming as they did from Servants and ignorant persons we did not know how far to credit them. This being the first week in August the weather was so intensely warm that there was scarcely any visiting though when ever we did meet any of our neighbors the whole conversation was of the state of Portsmouth and the necessity of leaving home. We were told that the cars and boats were no longer willing to take anyone from Norfolk27 and that there was but one way in which we could go by the Coffee28 a small steam boat in which we could reach the eastern shore or stop at any landing on the James River this was not the way we wished to have taken, so that we were in a state of suspense and indecision. Our trunks were however packed and we limited to two, for a party of five fearing that it would be difficult to take even these. Uncle Armstrong29 had been arranging a plan for some days to take his family in the Coffee on Sunday the only day on which he could have the disposal of her to City Point,30 or to Williamsburg. On Saturday night August 11th Father was told by his neighbor Mr. Wilson that there was to be an insurrection of the Servants, they supposing from the fact of the whites only being attacked that it was a judgment sent upon them, and a favorable time for a revolt.31 How true this is I do not know, but those who remained during the whole Summer say that their manner was very insolent during the first part of the fever, but when, they were themselves taken Sick32 and saw some of their companions die (though the number was at all times few as compared to the whites) they changed very much. This situation was very trying, they saw their owners flying from the pestilence which they were left to encounter and left in many cases very hastily and with inadequate provision for their support during the Summer.33 Father did not mention this to us at the time but we had enough to make us uneasy in the report which we heard at night that there were at that time fifteen unburied bodies in potters field which they could get no one to inter. The papers during this time would report one or two cases a day, fearing to alarm to citizens and to drive away trade.34 The next morning when it was still dark, I found Mother35 standing by me, she had come to tell us that Uncle Armstrong had just sent a note to inform us that the Coffee would be at Todd's Wharf36 at seven and urging us to join him. There were many advantages attending his plan he would have only those he knew on board and by taking the boat in out [our] part of town we would avoid passing through the infected districts which was thought very dangerous. But it was not in our power to go with them as we had made no arrangements about the Servants and there was too Short a time to do anything then. We felt a little sad at seeing the opportunity lost to us, and Mother who went to take leave of them called by on her return at the home37 they had left in such haste, everything showed the flight rather than determined departure of the inmates. Their hurried breakfast was just over and the whole house was open as is usual with us at this season, giving one an impression somewhat reminding us of the State of Pompeii when first discovered to have been abandoned in such haste that everything recalled their inmates.38

I was much engaged, yet wished to go to Sunday School,39 not knowing how soon I might leave them all. As I entered there were several teachers gathered in a little group, and I joined them and found they were confessing mutual fear and anxiety for the future. We talked together until Mr. Taylor opened the school although but a few children had come their parents fearing to expose them to the hot sun. I had but one scholar George Male and I tried to impress upon him the duty of seeking that hope which could alone give peace to the mind under such circumstances. Laura Malory40 who had no children set with me and expressed the sadness it gave her to hear of so many leaving town and hoped some would remain to cheer up others. Marian Southgate41 and Mrs Robinson42 were also there. These four I have marked I then saw for the last time, as they fell victim to this fatal scourge. At church there were also very few, and Mr. Walke43 who was preaching for us during Mr. Minnegrode's44 absence in Europe, seemed to feel very solemn in view of the duties before him, his wife who was there and heard his firm language calling upon the congregation to send for him in sickness and that it was his [kind?] desire to do all he could little thought that his life would be spared through all while she should fall. Father and myself walked home by the Academy45 where the Post Office had been removed thinking it more safe for the officers than on Main Street46. Mr. Galt was in church.47 Coming home we met Mrs. Henry Selden who said it was her husbands advice that all who could should leave town as soon as possible.48 Saw also Emeline Allmand in good spirits and laughing about the idea of running away in a little more than five days she had taken ill and died.49 Father saw Judge Baker50 who was anxious to make some kind of arrangements by which our families and those of Mrs. Klein51 and the Allmands could charter some steam boat to leave during the day. This carried him down into the very worst part of the town where he might have taken the fever. On reaching home I found them all ready to start with the trunks packed and Colbert Taylor who was to be of the party in the passage. The scheme was that we should go to New Port's News52 in a small sailing boat belonging to J Grady who had formerly been in Father's employment53 and considering himself under obligation agreed to land us there in time for the Roanoke54 to Richmond which passed there every Sunday and Thursday afternoon at four o'clock it was nearly one and our time was very limited, still Father had not come although the servants were in every direction looking for him. We took some ham and bread, and were very impatient until finally the subject of our solicitude made his appearance. When we mentioned this plan, he agreed to it at once, as the reports of the fever he had received downtown and also the difficulty he found in getting away made him ready to embrace any opportunity that could be presented. The trunks were carried to Drummond's Wharf with difficulty and we found that the tide was too low for the sailing boat to come to the shore we had to be rowed to her in a row boat with scarcely any sides. Chloe55 and myself went out first, standing up and in great danger of falling over every moment; this was the first inconvenience we met with in our flight. Mother and Mary56 came next, then Father and Colly and lastly the two trunks joined us. On the beach stood Aunt Peggy John and Sully57 waving an adieu to us, we felt very sorry to go without them, though Mother had made a very satisfactory arrangement for them during our absence. The evening was beautiful and the wind being in our favor we would at any other time have enjoyed the sail very much; but leaving our home and friends under such circumstances and for such a length of time made us all feel very solemn, and above all the day, the idea of spending Sunday in this way was anything but agreeable and it seemed as if we had no right to expect our undertaking to turn out otherwise than it did. And yet we could scarcely regret it, as the fever every one said was becoming more alarming and rapid in its progress every day, and had we waited until Thursday the next time the Jamestown58 went to Richmond, some one might have by that time felt the power of the destroyer. Never did our town look more lovely as we left it and never did there seem to be less to fear from remaining. The stillness of a Sunday evening in August was upon it, and yet going rapidly through the water as we were, the heat was not felt, so that we could calmly look upon our dear home, devoted as it seemed to be a prey to death. But oh how little did we then think of the terrible scenes that were to take place during the dark months that followed before we saw it again. We saw the ill-fated Ben Franklin which was the instrument of evoking all this woe, and further on at Crainey Island59 lay the Columbia, with its yellow flag still flying,60 which even in May seemed to give warning of the coming doom. As we ascended the James River the sail kept the sun from us, and Mother feeling a little seasick lay upon the cabin with her head resting in Father's lap.61 At last the landing came in sight and we hoped all was right when we understood that the Jamestown was not yet in sight. We were received on shore by the proprietor of the Hotel and having had a red flag put up to give notice that there would be persons to come from the wharf, we sat in the shade of a large quantity of wood, which was piled up in the yard. Here we remained until about five o'clock when hearing that the steamer was in sight, we walked down to the landing, and watched her approach with mingled feelings of hope and fear; but we soon found to our unspeakable disappointment that she would not stop to take us off. As we afterwards learnt the officers had been directed not to take passengers from any wharf near Norfolk. The question then arose, as to what we should do, for that very night at least we must spend where we were. They seemed to be very unwilling to have us stay fearing the yellow fever for though they did not know we were from Norfolk, they expected that was the case, and when we left there the proprietor told Colbert that he had been quite sure of it from the first. But as we were without shelter they consented for us to pass the night with them. Mr. Bennet a farmer living a short distance from the town invited us after a consultation with his wife, to spend the night at his house. Mary and myself went with him, leaving Mother, Father, Colly, and Chloe who were all put up in one room with a curtain between. Mr. B's house was a small one but very prettily situated.62 We found Mrs B, with another lady and a young gentleman, ready to receive us. The tea table was set and everything looked very comfortable except Mrs Bennet who was evidently afraid of us and sat off as far as possible. When tea was over we sat on the porch which was open to the water, giving us a fine view and a delightful breeze, several small boats passed, and among others the Coffee on her return trip, having either landed our friends in safety or bearing them back to the fever and the fear at least if it should prove nothing else of an insurrection which was said to be planned for the night. As she came in sight the twinkling of the cabin lights on the water and the long line of sparks still in view for some moments when the boat herself was out of sight, seemed to give us hopes that there were no sad hearts on board and that we too should also see glad days yet in store for us. All around us they were speaking of the persons who had gone up the river in the morning and of their probable fate but the general impression seemed to be that as they had not stopped to put on shore those from his neighbor's land, they must have landed at City Point. About nine o'clock we heard a boat hailed from New Port News, and as she stopped we concluded that father had made some arrangement to go on the next morning. We were given a little room next [to] the parlor, where every thing looked nice, and reminded us that we were in the country in a great many ways which were all pleasant, and the next morning I was aroused by the voice of an old woman calling the fowls which were being fed on the grass just under our windows. I was interested in watching them, particularly as we did not like to leave our room as it opened in the parlor which our host had occupied as a chamber the night before. We had just taken our seats at the breakfast table, when a messenger came to tell us to join them at NPort as soon as possible to go on board the schooner. I was so impatient to join them that I walked on with the messenger and Mary followed with Mr Bennet. We were in very good spirits, at the prospect of going on, and being most of us perfectly unacquainted with the many disagreeables attending a sailing expedition in a boat of that size particularly, we went on board that bright Monday morning looking forward to reaching Petersburg that evening or the next morning at least. The sails were in just the right position to keep the sun off, and we took our seats on some red stone steps which they were carrying for a church in Petersburg. Mr. Bennet and some of the others came with us [and] shook hands in parting our friend Mr B apologizing for his wife's want of politeness on account of the state of her mind about the sickness in Norfolk, and the extreme fear she felt of meeting with some one from there adding as he took leave of us that he really pitied us, attending to out present situation, a piece of consideration which we considered quite uncalled for, but found to our sorrow, that his pity was well bestowed knowing as he must have done that it might be several days before we would reach our destination, he seemed to feel for us so much that but for his wife's anxiety I think he would have tried to induce us to wait for a better opportunity. We enjoyed the breeze and the view of the Shore on either side, until dinner was announced to be ready, which on descending to the cabin we found to consist of some boiled pork corn bread and some rolls far too heavy with fat to be eatable and tea which had to be stirred with a knife as there was no spoon on board. Every thing however passed off for a joke, even the repu[ta]tion of the same at night. But the berths we found could by no means be used by us, so Father stretched himself on the two trunks which were placed in the middle of the cabin with the carpetbag for a pillow and his great coat to cover with and we lying around him in a sort of bunch running entirely around the cabin which was very small. Tuesday was spent in some way, how I can hardly say, being afraid to sit in the burning sun and frequently made sick by the bilge water so that it was impossible to remain in the cabin. Mary fortunately had a bottle of cologne which was the only thing to revive Mother at all. The sugar gave out which made very little difference as it was extremely bad at first. The ships company were it seemed entirely unacquainted with the proper course, or how to guide the vessel. None of them having ever come up the James river except the pilot who had visited Petersburg twenty one years ago. Such being the case, our course was very slow and Tuesday and Tuesday night we made little or no progress. We were much disappointed not landing at Jamestown63 as a breeze had just sprung past us and the captain though[t] it better not to stop though we were so slow in passing it I am sure we would have had time to go on shore. Wednesday morning we saw an old coloured man in a row boat who was carrying water and musk melons to Petersburg for sale, who we made some purchases of, and he was finally engaged to pilot us to the City he fastened his little boat to ours and came on board. With his assistance we reached Petersburg that evening after two of the most disagreeable nights and three of the longest days I ever remember to have spent. Our old pilot under took to conduct us to the Bolinbrooke Hotel64 which we looked upon as a haven of rest. We were shown to our rooms opposite each other and as comfortable as possible. We took supper again at a table and not standing around the cabin as had been our habit for some days past, and commenced to feel [a] little respectable again, a feeling which I feared would never be mine any longer and I also rejoiced in seeing no more of our tragic cook, and that we had heard the last of the helmsman's favorite air, "Oh you are too sweet for me." The next morning Mother Mary and Father took a walk before breakfast, and we were much afraid of being left as the cars went at an early hour, but they returned in time, and we took the railroad to Lynchburg in the cars a gentleman from Alabama introduced himself to me at first by sundry attentions65 in putting up and down the window near me, and finally by giving me his name on a slip of paper DeGW Vaughan Tuscaloosa Aa.66 He joined us coming from the cars and went with us to the Norval House, which we reached just before dinnertime. In the afternoon Mr Waller and Mr Speed came to see us67 and Mr W walked out with [ ]. Lynchburg is not a pretty place and the streets are very hilly, The next morning Mr Speed Mr Waller and some other gentlemen called and at one o'clock we went down to the cars, where we saw Dr Barraud68 in a very anxious state about Mr B—also saw the Kleins in the cars and traveled with them as far as Bedford's Depot, where we got out and took the stage for Buckanan.69 This stage drive I shall never forget winding as we did around the side of a very high mountain but the scenery was beautiful, particularly as we reached B—just before dark. It is a pretty village lying at the feet of lofty mountains enclosing it on all sides. We found many persons at the Botetourt House70 from Portsmouth who had been there for some time. At night Mr and Mrs Mays called to see Mother and Father and Annie Mays and Mr Whiting to see us.71 There were several other persons we knew there who we expected to see on our return from the Bridge.72 Left our trunks here intending to return the same evening, that is to say Saturday which morning we left B— for the Natural Bridge a beautiful day and all well and looking forward to a delightful visit we had long contemplated. Having read in a late account that the bridge was so situated that it was crossed before you became conscious of it being so near,73 we looked out with great attention but saw nothing to interest us particularly until we stopped before the door of a pretty looking country tavern. Here we left our shawls and everything that we could dispose of and procuring a guide,74 we set out for the Bridge the walk to it was in itself so beautiful, first passing through a wooded path that crossed the top of the mountain under which is the bridge. When we began the descent it was very different as our way led through and around large masses of rock around which there were winding various little streams, which when swollen with the rains of winter must form a succession of cascades extending over a distance of some thirty yards and covering the way we were now taking; on every side, there were the beautiful forest trees of America and mingled with them many varieties of the life everlasting which must always preserve some of the brightness and verdure connected with the spot. When the arch was first in sight we were compelled to give so much attention to our footsteps as to be unable to obtain a perfectly safe standing place to admire the beauty of the scene. The James river over which the bridge passes is sometimes75 very shallow but on the day we visited it, the previous rains had increased it so much that the highest points of the rocks were alone uncovered so that we were able to step from one to another until we reached a ledge of considerable width when looking up we beheld far above us the dark stone vaulting of the arch. The base on either side of us is nearer the middle by several feet than above, the rocks forming seats and natural steps for some distance and no doubt the water acting on them have during the course of years produced many changes so that if General Washington really wrote his name on the spot76 pointed out it may have been a much less disastrous attempt than it would be at the present time. It was with difficulty that we could distinguished the initials as they were at a great distance from us and much worn by time. The rocks (at least below) are so hard that an attempt by one of our party to make an impression upon them with a penknife was almost an entire faillure. This I should think would be still more difficult higher up and the letters are of such a size, that they must have required some time and a much firmer foothold than any as can none discover to cut them. Immediately beneath the bridge are a few trees, growing, but they were small owing I suppose to the want of sun and heat. Although quite a warm day, the coolness was unpleasant and I felt the want of a shawl as a means of enabling me to enjoy the scene to its fullest extent. Alas, for human nature! Through both sides the view is beautiful, mountain and forest combined with the unpretending little stream gliding peacefully on in the sunlight, as if unconscious of man's wonder and awe felt at the sight of the [ ] structure nature has thrown over it, denied to so many mightier and more renowned rivers. Above we could plainly see the spread eagle,77 which is formed of the mould and moss under the upper part of the arch, and it is really very much like our national emblem. We turned away after some time, feeling that though we would willingly remain longer, yet that we had now a new pleasure in store for us, the power to call up a call among our other pictures of memory this of the Natural Bridge of Virginia. I afterwards approached the edge as nearly as I could with safety, and saw the view from above which is entirely different and from the opposite side. My new friend78 asked if I should forget him, and the walk to the bridge we had taken together. The following answer I write in Lexington and though he never saw it, I will give it a place here as being connected with this delightful day.I will not forget thee, I could not destroy,

The bright threads of memory so woven with joy

So long as the view of that arch I retain,

So long must thine image there engraven remain.

I will think of the help thy ready hand gave,

When each rock that we stepped on was washed by a wave,

And remember thy words which have shown me how some

Two hearts of it beauty could feel but as one.

And oft in the future will recall every scene

As the [ ] pass over the fields they would gleam,

And recalling high hopes and warm wishes will rise,

For him who stood with me beneath those bright skies.(Here I must say that the above is to be interpreted as a poetical license, for though I often think of the Natural Bridge the attendant circumstances very seldom intrude[)].

The rest of the party having decided it a thing not to bethought of to return to the Botetourt House, and altogether impossible to go back in the same way we came, I found myself disappointed of an idea I had begun to cherish of spending the next day Sunday in this charming spot, for though we would not be able to attend divine service I felt that for myself at least there might be even more solemnity in worship[ing] him in spirit in this temple not made with hands. But a few moments consultation determined us and we were soon rolling over a rocky road in one of those old fashioned stages which are now so fast disappearing. How often during this little excursion were my feelings enlisted first for the safety of our party and then for the poor horses who have far too little time given them to rest and the thought of whose fatigue was sparked many a [ ]. Reached Lexington about seven o'clock that afternoon, and found ourselves installed in two very pleasant rooms, on the lower floor of the McDowell House whose old and much to be respected proprietor,79 paid us very kind attention, as we then thought both in and out of season, Ah how ungrateful we then were for his pressing inquiries whether we would choose ham or beef and how uncalled for we thought his encouraging descriptions of every thing upon the table, but we lived to learn in a few weeks that there were but few McDowells on the road, and often to speak with each other of his white bread and butter, and of his quiet pleasant house. At night I found my way to an upper parlor where I amused myself with the piano, until Col Garnett80 and Major Williamson came in to see us, as we expected to leave on Monday. They fixed upon the next afternoon at four for us to visit the Military Institute.81 In the morning at eleven Miss Williamson came for us to go to church, we sat in her pew and heard a very good sermon. After dinner wrote a letter to Aunt Peggy, who I promised should hear from me as soon as possible. This day we saw the first news from Norfolk, since we had left home and fearful indeed had been the ravages of the destroyer. We met the names of many we knew among the sick, and Dr Sylbistre82 and Emeline Allmand were reported dead with others. From this time the mails brought sadness to our circle and day by day we would watch to hear of this or that friend, the announcement of their sickness generally preceding that of their death but a day or two. In church prayers were offered up for our afflicted City. At four o'clock, we set out though it was still quite warm, called first at Major Williamson's house,83 where we saw the family and remained some-time. On the way to the institute met Frank Smith84 who went over the buildings with us. Admired the order and neatness of everything visited the mess hall which is a distinct building and returned after sundown. Found our friend Mr Poindexter85 there, who staid until tea time. Went to church, and heard my home often spoken of in words of pity alluding to the bad news just received. Found Mr Patton with Mary on my return. The next day our trunks did not arrive, and we began to feel quite uneasy about them. Spent the day in shopping visiting the Daguerrean gallery86 with Mr P had some visitors. Tuesday about three o'clock the long looked for trunks made their appearance and we began to get ready for Rockbridge Alum87 with great pleasure. Left Lexington about five and reached Rockbridge at eight. As we drove up to the hotel, the lights were gleaming from the cabin windows which form a half circle around it. The crowd was very great and we could only procure two very small rooms where Mary and myself in vain looked for someplace to hang our bonnets traveling dresses & on, but seeing nothing of the kind were obliged to lay them in heap upon the floor. Having dressed in the greatest hurry, we were escorted to the ball room which proved to be a small and badly arranged room crowded with persons in every variety of costume. Danced two setts and was very glad to retire to our limited quarters, quite worn out with our journey. Walked down to the springs before breakfast, as it is thought of great Service at this time. The springs are formed from the drippings of an alum rock which seems as if [it] was cut perpendicularly from the side of the mountain. They have a gloomy look, as the rock is dark in coloring and there is a covering over them. There are five different degrees of strength,88 but I got no farther than the first as the taste is extremely bitter. After breakfast played ten-pins, with a number of other persons until it became too warm for such exercise. When we returned to the parlor and made up a party at whist Mary, Mr Patton, a Mr Waddy and myself until the time came for us to dress for dinner.89 Took a delightful walk in the afternoon, and played whist again. Did not go that night to the ball room as it was raining very hard. The next day was much like the first except that we were more successful at the ally, beating a very boastful party who we were informed practiced constantly in a private ally. Played whist with a friend of Mr Patton's Mr Glascoe, also another person whose name I have forgotten. Left rather suddenly at four in the afternoon for the Bath Alum, delightfully accommodated in an extra containing our family and Mr Patton. The road that we passed over was very picturesque, at Milboro we saw Dr Newton90 who was staying there with his family he came to the side of our stage and we talked our Norfolk affairs together, and gave each other the news we had received. Reached the Bath Alum91 that night too late to see much of it, but the houses seemed to be well and comfortably built, though the whole appearance of the place showed that it was only visited by invalids, and these were too few to support the establishment according to the expectations of the builders.

Repaired to the so called ballroom which is a rather large apartment the band consisting of two colored fiddlers whose music I heard afterwards preferred to the White Sulphur band, which was a pair of volantes92 from Baltimore. Found here Mr and Mrs F Robertson93 with their daughter from Norfolk. Mr P introduced a young gentleman to us who we alternately danced with and Mr P until about eleven when we sought our rooms to find some rest before starting the next morning at five. Found in the stage Mrs and Mr Robertson and Olivia also Dr and Miss Taliaferro, who all went on to White Sulphur we remaining at the Warm Springs.94 Enjoyed the delightful prospect from the top of the mountain very much. The sun was just rising, and the clouds below us looked like a beautiful lake surrounded by mountains on all sides. As we had eleven persons inside and out besides the baggage the gentlemen walked and the horses had indeed enough to do as it was. We were shown to a sweet little cottage which made me realize being at the Springs for the first time, staying in the hotel at the Rockbridge Alum was not at all the idea I had formed. Went took breakfast as soon as we could felt sufficiently settled in to attend to any thing where between Mr Patton's being well known to every one and Mr Spangler entertaining a truly Virginian chivalry in assisting ladies, we were well taken care of. We reached the Warm Springs on Friday morning and remained there until the following Monday at the same hour. Sunday morning Mr Patton left us and his friend Mr Glascoe arrived who also staid until Monday. Went to church in the Court House on Sunday morning and heard a sermon from a Methodist minister. In the afternoon attended the Episcopal church which is a very pretty one, not quite finished at that time. I shall ever remember the beautiful scenery, delightful water, and sweet seclusion of this charming spot, as among the many pleasing recollections of the summer.

On entering the stage for the White Sulphur95 we found Mr and Mrs Blaire of Richmond with a baby and nurse96 also Mrs Thompson her son, Mr Poindexter her brother, and her niece Ella Poindexter as our traveling companion. We were not at all acquainted until this time97 but the day's travel made us know each other very well, particularly as Mr P was very talkative from the first and so good natured it was impossible not to like him. Stopped at the Hot Springs98 for breakfast, and the younger portion of our company proceeded to visit the different Springs and bath houses. I was disappointed in the heat it did not appear to me to be much higher than that of the Warm Spring but prehaps it varies in the degree of heat. Returned to our Stage Father Mr Blair and Mr Thompson on top, and we were very anxious about our different friends as a rain came up and horses would become frightened if an umbrella was raised. The baby in the meantime varied the scene by emptying the bottle of milk Mrs Blaire had filled, and crying occasionally to the great grief of Mr B who could only hear its lamentations without knowing whether they were called for or not. But we all took much interest in our Baby as Mother called him and therefore no one was annoyed by the noise or trouble he caused. As evening came on we reached a tavern built on what they call the dry creek a mile or two from the White Sulphur, here they told us it would be impossible to find accommodations at the Springs and predicted we would have to return and stay there this made us all determine, rather to go anywhere else in such a case. Also passed Marstons where John Barraud was sitting on the front porch with his white hat on."99

As they had told us, we learnt that there was no room at the Springs but if we would stay at Marstons for a few days the first vacancy would be for us. This we were obliged to do, after some discussion Mrs Thompson, her niece and Mary and myself were all put in the same room went down to the Spring before night to drink a glass of water. Met Mrs Roland and Mrs Baylor from Norfolk.100 At night it was raining a little but hoping it would stop Mary and myself determined to go to the ballroom. Father Mr P and Mr T accompanied us; found very few there and heard some amusing complaints of the dullness of the ball in general, returned in one of the hardest rains I ever was out in but it only made us laugh the more. Saw Lieut Rich the next morning he came in to see us and promised to bring his guitar and play for us. Father and the other two gentlemen went over to see about rooms, and returned with the good news that Mr Caldwell had immediately given Father a Baltimore cabin for our party. Locked our trunks with the greatest pleasure, and leaving them to follow, we soon reached our cottage which we were delighted with, it was built with five rooms a parlor and four chambers. The last on the Baltimore Row just by a very romantic walk around a mountain at the base of which the Row is situated. It commanded a fine view of the Springs with the different little cabins scattered about in front and farther off the mountains stretched in every direction seeming to enclose and protect the humble cottages which looked so small in comparison. The crowd was so great that for a week or two we dined in the porch where a long table was spread. We soon fell into the regular course of such places, every morning going to the Spring before breakfast then meeting at the reception rooms to talk a short time before taking a game of ten-pins, the ally was not good but we could enjoy seeing how often the balls rolled off when there was no other amusement. Returning by the Spring to drink one or more tumblers according to the [reso]lution at your command a short time to rest when the first dinner bell rang; after dinner a walk and the ball at night completed the day. Mr Thompson and myself enjoyed the walk around the mountain one morning about 2 o'clock, for though it was quite warm.101

1. Grace considered the mosquitoes an annoyance, not a threat. It was not until the research of the U.S. Army Yellow Fever Commission was undertaken in 1900-1901 (under the direction of Walter Reed) that a link was established between the Aedes aegypti mosquito and the transmission of yellow fever. "Walter Reed," Dictionary of American Biography (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1935), 15: 459-461; Conway Whittle to Frances M. Lewis and Mary W. Neale, 13 October 1856, Conway Whittle Family Papers, Swem Library, The College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia [WFP]; Lawrence W. Brewster, Summer Migrations and Resorts of South Carolina Low-Country Planters (Durham: Duke University Press, 1947), 42; Margaret Humphreys, Yellow Fever and the South (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1992), 5.

2. David R. Goldfield, Urban Growth in the Age of Sectionalism: Virginia, 1847-1861 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1977), 154; Report on the Origin of Yellow Fever in Norfolk During the Summer of 1855. Made to City Council, by a Committee of Physicians (Richmond: Ritchie and Dunnavant, 1857), 20-22, 26-28; Betsy Fahlman, Beth N. Rossheim, David W. Steadman, and Peter Stewart, A Tricentennial Celebration: Norfolk 1682-1982 (Norfolk: The Chrysler Museum, 1982), 67; Richmond Enquirer, August 2,1855. A detailed view of Norfolk in 1850 was recorded by George P. Worcester, Civil Engineer, in his "Map of the City of Norfolk with Portsmouth and Gosport," 755.52 1850, Library of Virginia [LVA].

3. Jo Ann Carrigan, "Yellow Fever: Scourge of the South" in Disease and Distinctiveness in the American South, eds. Todd L. Savitt and James Harvey Young (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1988), 58-59; Report on the Origin of the Yellow Fever, 40.

4. W. H. Coffin, The Art of Medicine Simplified, or a Treatise on the Nature and Cure of Diseases, for the use of Families and Travelers (Wellsburg, Virginia: W. Barnes and Company, 1853), 94-95; David Holmes Conrad, Memoir of Reverend James Chisolm, A. M., late Rector of St. John's Church, Portsmouth, Virginia, with memoranda of the pestilence which raged in that city during the summer and autumn of 1855 (New York: Protestant Episcopal Society for the Promotion of Evangelical Knowledge, 1856), pp. 95, 98; Grace Whittle Diary, 2, WFP; Anne P. B. Herron to Frances M. Lewis and Mary W. Neale, 27 August 1855, WFP; Richmond Enquirer, 5-6 September 1855. During the 1878 yellow fever epidemic in Memphis, half of the city's inhabitants fled; a quarter of those who remained died. Mary E. Stovall, '"To Be, To Do, and To Suffer': Responses to Illness and Death in the Nineteenth-Century Central South," Journal of Mississippi History 52 (1990): 95-109.

5. Report on the Origin of the Yellow Fever, 31, 33-35; Armstrong, Summer of the Pestilence, 20,45; Conway Whittle to Mary W. Neale and Frances M. Lewis, 3 August 1855, WFP; Richmond Enquirer, 2, 8, 13-14 August 1855; Minutes of the Common Council [Norfolk City], No. 8, 1 January 1856; Mutual Assurance Society of Virginia, Declarations and Revaluations of Insurance, Policies 177A, 17824, LVA.

6. Sarah Virginia Weight Hinton Diary, 9 August 1855, Swem Library, The College of William and Mary; Richmond Enquirer, 9 August 1855.

7. Memoir of Reverend James Chisolm, 89, 91-107. Chisolm died on 11 September 1855, after remaining in Portsmouth during the epidemic; two of his sons also died. "He, being dead, yet speaketh ": A Discourse on the Death of Rev. James Chisolm, preached by request of the Vestry, December 16, 1855, in St. John's Church, Portsmouth, by Rev. Charles Minnigerode, D. D., Rector of Christ Church, Norfolk, in Memoir of Reverend James Chisolm. Additional Sisters of Charity were sent from Emmetsburg and St. Joseph's, Maryland. Richmond Enquirer, 2, 7, 15 August 1855.

8. Patricia C. Click, The Spirit of the Times: Amusements in Nineteenth-Century Baltimore, Norfolk, and Richmond (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1989), 227; U. S. Census, State of Virginia, Slave Schedules, 1850, Norfolk County, National Archives Microfilm Publications (NAMP); Personal Property Tax List, Norfolk City, 1854, LVA.

9. Anne P. B. Herron to Frances M. Lewis and Mary W. Neale, 27 August and 13 September 1855, WFP.10. Armstrong, Summer of the Pestilence, 54-55, 72. Armstrong argued that blacks had "little to fear" from the fever; Report on the Origin of the Yellow Fever, 38; Carrigan, Yellow Fever: Scourge of the South," 62; Todd L. Savitt, Medicine and Slavery: The Diseases and Health Care of Blacks in Antebellum Virginia (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 241-243; Bureau of Vital Statistics, Norfolk City, 1855, LVA; Anne P. B. Herron to Frances M. Lewis and Mary W. Neale, 27 August 1855, WFP.

11. Minutes of the Common Council [Norfolk City], No. 8, 16 September 1855.

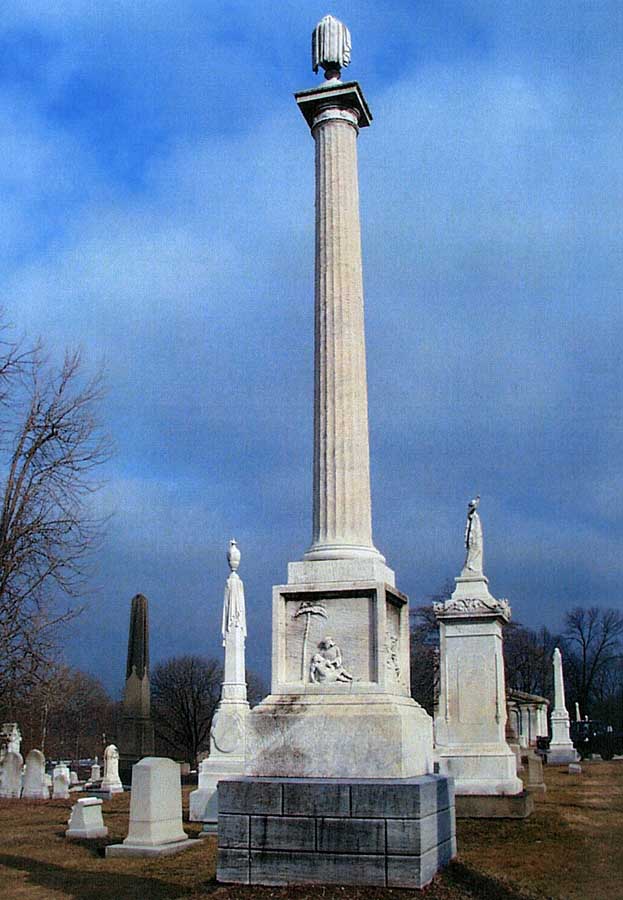

12. Mary Thompson to Mary W. Neale, 7 August 1855, WFP; Richmond Enquirer, 2 August 1855; Click, Spirit of the Times, 14; Peter C. Stewart, The Commercial History of Hampton Roads, Virginia, 1815-1860 (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Virginia, 1967), 220; William S. Forrest, The Great Pestilence in Virginia; being an historical account of the origin, general character, and ravages of the yellow fever in Norfolk and Portsmouth in 1855; together with sketches of some of the victims, incidents, of the scourge, etc. (New York: Derby and Jackson, 1856), 1; George D. Armstrong, A Summer of the Pestilence: A History of the Ravages of the Yellow Fever in Norfolk, Virginia, A.D. 1855 (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1856), 190; Conway Whittle to Frances M. Lewis and Mary W. Neale, 3 August 1855, 26 September 1855, WFP; Grace Whittle Diary, 3, WFP; Cedar Grove Cemetery [Norfolk, Virginia], Epitaphs.

13. For another extraordinary diary of an ordinary woman, see Christine Jacobson Carter, ed., The Diary of Dolly Lunt Burge, 1848-1879, in Southern Voices From the Past: Women's Letters, Diaries, and Writings, Carol Bleser, general editor (Athens: The University of Georgia Press, 1997), xi-xii. Conway Whittle to Frances M. Lewis and Mary W. Neale, 26 November 1855 (where he reported that the family "arrived safely at home Wednesday last"), 13 October 1859, WFP; Grace Whittle Diary, 3-4 and passim, WFP. On October 19, the Richmond Enquirer advised its readers who were planning to return to Norfolk to wait until the first heavy frost. The Whittle family's trek westward can be traced on a "Map of Routes and Distances to the Virginia Springs," included in John J. Moorman's The Virginia Springs: comprising an account of all of the principal mineral springs of Virginia. . . Second Edition. (Richmond: J. W. Randolph, 1857).

14. The 1850 Norfolk County census schedule (which encompassed Norfolk City) lists Thompson's age and her husband's occupation, as does William S. Forrest's Norfolk Directory for 1851-1852: containing the names, professions, places of business, and residences of the merchants, traders, manufacturers, mechanics, heads of families, &c, together with a list of the Public Buildings, the names and situation of the Streets, Lanes, and Wharves; and a Register of the Public Officers, Companies, and Associations in the City of Norfolk. Also, information relative to Portsmouth with a Variety of other Useful, Statistical, and Miscellaneous Information (Norfolk, 1851). Mary Thompson to Frances M. Lewis and Mary W. Neale, 28 June 1855; 14 July 1855; 7, 18, 25 August 1855, WFP. The Norfolk County census also lists ages of Imogene Barron and her children; her daughter Lizzie's death was reported to the Bureau of Vital Statistics by the Howard Association on 17 August 1855.

15. Anne P. B. Herron to Frances M. Lewis and Mary W. Neale, 27 August 1855; Norfolk City Register of Deaths, 17 September 1855. The 1850 Norfolk County census schedule lists Herron's age and her brother's occupation: physician. He was a director of the Norfolk Drawbridge Company, along with Conway Whittle, and a solicitor of funds for the Norfolk Humane Association for the Relief and Improvement of the Poor. Norfolk Directory, 95, 97. The 1855 Norfolk Personal Property Tax Lists [LVA] provide the number of slaves Herron owned, among other possessions. For a brief biographical sketch of Herron, see Rogers Dey Whichard, The History of Lower Tidewater Virginia (New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Company, 1959), 1: 467. Her philanthropic activities are described by Sister Mary Agnes Yeakel in The Nineteenth Century Education Contribution of the Sisters of Charity of St. Vincent DePaul in Virginia (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1939), 57-59; among them, St. Vincent DePaul Hospital and Saint Mary's Female Academy and Orphan Asylum, both administered by the Sisters of Charity.

16. Elizabeth Whittle to Frances M. Lewis and Mary W. Neale, 20 August 1855, WFP; Elizabeth Whittle's age and the number of her children is listed in the 1850 Norfolk County census schedule. Her death is listed in William C. Whittle's family Bible, along with their son Arthur's. WFP; Mecklenburg County Personal Property Tax List, 1855 [LVA]; Bureau of Vital Statistics Deaths, Norfolk City, 30 August 1855, 3 September 1855, LVA; Richmond Enquirer, 3 September 1855; Mary Thompson to Frances M. Lewis and Mary W. Neale, 7 September 1855, WFP.

17. Mary Thompson to Frances M. Lewis, 25 February 1856, WFP.

18. For some Whittle family members, spiritualism offered immediate, tangible rewards, while the more traditional comforts of religion (that families would be reunited in heaven in "an unbroken circle") required patience and faith, scarce after the devastation of the summer. Stovall, "To Be, To Do, and To Suffer," 108-109; Jean E. Friedman, The Enclosed Garden: Women and Community in the Evangelical South, 1830-1900 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1985), 5; Mary Bednarowski, "Women in Occult America," in The Occult in America, Howard Kerr and Charles L. Crow, eds. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1983), 179; Howard Kerr, Mediums, and Spirit-Rappers, and Roaring Radicals: Spiritualism in American Literature, 1850-1900 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1974), 3, 5.

19. Grace Whittle Diary, 3. WFP; Mary Thompson to Frances M. Lewis and Mary W. Neale, 9 September 1855, WFP; Helen Wilson, "spinster," died on September 2 from the fever. She lived with the family of William Stark, a captain in the United States Marine Corps, and was likely the sister of his wife Elizabeth. In 1855, Wilson was fifty years old. The Stark family is listed just before the Whittles in the 1850 Norfolk County census schedule; Bureau of Vital Statistics Deaths, Norfolk City, LVA; Conrad, Memoir of Rev. James Chisolm, 91; Richmond Enquirer, 7 August 1855. Minutes of the Common Council [Norfolk City], No. 8, 3 August 1856.20. Mary Thompson to Frances M. Lewis and Mary W. Neale, 18 August 1855, 7 September 1855, 3 October 1855, WFP.

21. Horace H. Sams, Compiled Confederate Service Record, National Archives and Records Administration; Cedar Grove Cemetery [Norfolk, Virginia], Epitaphs; Cloe Tyler Whittle Greene Diary, 22 May 1865, 5 January 1873, WFP; Richard J. Finneran, ed., The Collected Works of William Butler Yeats. Volume 1: The Poems (New York: Macmillan, 1989), 187.

22. Grace's blank journal was purchased from Vickery and Griffith, "Booksellers, Stationers, and Dealers in Fancy Articles," located at 19 E. Main Street (at the head of Market Square) in Norfolk. In the 1851-1852 city directory, the store advertised schoolbooks, hymnals, Bibles, stationery, and "BLANK BOOKS, embracing every description of Account, Record and Memorandum Books." Norfolk Directory, 81 and, in the City Advertiser section, 6. Grace Whittle's diary is part of the Whittle Family Papers at Swem Library, The College of William and Mary and has been microfilmed as part of American Women's Diaries: Southern Women (New Canaan, Connecticut: Readex Film Products, 1988). Other Whittle papers have been filmed as part of Southern Women and Their Families in the Nineteenth Century: Papers and Diaries. Series C, Holdings of the Earl Gregg Swem Library, The College of William and Mary in Virginia, Miscellaneous Collections, 1773-1938 (Bethesda: University Publications of America, 1994),

23. the Steamer Ben Franklin: The Ben Franklin arrived on 5 June from St. Thomas. Bound for New York, it stopped for repairs in Hampton Roads. American Beacon, 6 June 1855, "Marine News"; Report on the Origin of the Yellow Fever, 20-21; Tommy L. Bogger, Free Blacks in Norfolk, Virginia, 1790-1860: The Darker Side of Freedom (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1997), 126.

24. Mrs. Barren the wife of the captain: Imogene Barron, wife of Captain Samuel Barron, commander of the Gosport Navy Yard in Portsmouth, where the fever first manifested itself. She was forty-six years old in 1855. The 1850 Norfolk County census lists five children in the Barron household (Samuel, Imogene, Elizabeth H., Virginia, and James, ranging in age from fourteen to one.) Barron died on 8 August, her daughter Lizzie on 17 August. Sarah Hinton noted in her diary on 9 August that Barren's "sad fate" was mentioned in the city newspaper. Mary Thompson wrote to Frances M. Lewis and Mary W. Neale about Barron's illness on 7 August, relaying news from Henry Selden, the consulting physician, that her case was proceeding favorably; on 18 August, Thompson reported that Imogene had died ten days earlier and was buried at night, that her husband was ill, that the children were infected and that one child (Lizzie) had already succumbed to the fever. William Jackson noted Imogene's death in his diary on 9 August: "I buried Mrs. B. last night, in the stillness and darkness and gloom of the night, between 10 and 11 o'clock. It was a deeply solemn occasion." George D. Cummins, A Sketch of the Life of the Rev. William Jackson, Late Rector of St. Paul's Church, Norfolk, Virginia (Washington: Gray and Ballantyne, 1856), 85-86; WFP; Lynchburg Daily Virginian, 11 August 1855.

25. Rev Mr. Jackson: William Jackson (1809-1855) had been minister of St. Paul's Church in Norfolk, at the corner of Freemason and Duke Streets, since 1849. He died during the epidemic; in 1856, the General Assembly chartered an organization to provide care for children orphaned by the fever and named it in his honor. Jackson Orphan Asylum, Norfolk, Virginia, Records, 1859-1922, Misc. Reel 806, Accession 30972, LVA; Cummins, Life of the Rev. William Jackson.

26. Barry's Row . . . set on fire: Richmond Enquirer, 13, 15 August 1855.

27. no longer willing to take anyone from Norfolk: Mary Thompson reported to Frances M. Lewis and Mary W. Neale on 7 August that, at Old Point Comfort, "the Norfolk boats are not allowed to come to the wharf to land passengers . . . and neither the Baltimore or James River boats come further than this place." Quarantine in Norfolk made it difficult, but not impossible, for residents to flee. (WFP).

28. the Coffee: At the height of the epidemic, the steamer J. E. Coffee met boats from Richmond and Baltimore out in the harbor, to collect deliveries of mail and coffins. The steamer advertised in the 27 June 1855 Southern Argus that it was "a long established and regular line," offering service between Norfolk, Old Point, Hampton, the Eastern Shore, and Mathews, as well as excursion trips. The "popular and well-tried" vessel had just been renovated and an upper deck added for summer travelers. Two steamboat captains were listed in the Norfolk City Bureau of Vital Statistics Death Register for 1855; one was the captain of the Coffee, John Hicks, who died on 22 September at age seventy-five. His daughter Henrietta died on 14 September; both deaths were reported by the Howard Association. Armstrong, Summer of the Pestilence, 102- 103.

29. Uncle Armstrong: U. S. Navy Captain William Armstrong (1799-1861) lived at 120 W. Bute Street with his wife Adelaide Tyler Armstrong (1806-1881), Cloe Tyler Whittle's sister. The three children lost in the scarlet fever epidemic were Rebecca (27 January 1832-9 September 1841), Mary Laura (23 November 1835-11 September 1841), and Joseph M. (16 January 1837-29 September 1841). They are buried with their parents at Norfolk's Cedar Grove cemetery. William Armstrong and Adelaide Tyler were married at Norfolk's Christ Church on 20 August 1827; the 1850 Norfolk County census lists their eight children, ranging in age from two to twenty-two. The Norfolk Directory lists Armstrong as a commander attached to Gosport, 110.

30. City Point: At the convergence of the James and Appomattox Rivers, near Petersburg, City Point was the port of entry for Prince George County and handled trade by water and rail for nearby Petersburg and Richmond. Richard Edwards, Statistical Gazetteer of the State of Virginia, embracing important topographical and historical information from recent and original sources, together with the results of the last census population, in most cases, to 1854 (Richmond: Published for the Proprietor, 1855), 209.

31. Father was told by his neighbor Mr. Wilson: Mr. Wilson may have been Josephus Wilson, a merchant who owned a dry goods store at 37 E. Main Street. Conway Whittle's law office was located at 74 E. Main Street. Norfolk Directory, 82-83; U. S. Census, State of Virginia, 1850, Population Schedules, Norfolk County, NAMP. An insurrection of the Servants: City officials in New Orleans feared a slave plot in June 1853 during that city's yellow fever epidemic; they placed armed patrols on the streets, called out some units of the local militia, and made several arrests. Carrigan, "Yellow Fever: Scourge of the South," 62.

32. they were themselves taken Sick: Many whites believed that blacks were immune to the fever; as a result, they frequently served as grave diggers and even nurses as the epidemic progressed. Blacks of West African descent did possess "an innate defense mechanism" which protected them from the most deadly form of the fever; while they contracted the disease, they rarely died from it. Savitt, Medicine and Slavery, 241-243. Bogger, Free Blacks in Norfolk, 125.33. they saw their owners flying from the pestilence: As mentioned by Anne P. B. Herron, in a letter to Frances M. Lewis and Mary W. Neale, 27 August 1855, WFP.

34. The papers during this time would report one or two cases a day: The Norfolk Southern Argus dismissed reports of the epidemic for six weeks, although the news had already begun to appear in the Richmond papers. Goldfield, Urban Growth, 153; Report on the Origins of the Yellow Fever, 26.

35. Mother: Grace's mother Cloe Tyler Whittle (1802-1858), daughter of Judge Samuel Tyler and Eliza Bray Tyler. She married Conway Whittle on 19 February 1824.

36. Todd's Wharf: The wharves began at Town Point; "the outward line of the wharves from the extreme end of Town Point to the Draw Bridge," according to the Norfolk Directory, "forms a tolerably regular curve, equal to about one fourteenth of the circumference of a circle," 35.

37. the home they had left in such haste: The Armstrongs lived at 120 West Bute. Norfolk Directory, 44.