Early

Pensacola Navy Yard in Letters and Documents

to the Secretary of the Navy and Board of Navy Commissioners

1840-1850 (Part III)

By John G. M. Sharp

At

USGenWeb Archives

Copyright All right

reserved

Note: Complaints about the illegal sale of liquor such as brandy, whiskey, gin, rum and wine on Pensacola Navy Yard, and the villages of Warrington and Woolsey, under “the entire control of the commandant” were commonplace.1 W. J. Rorabaugh in The Alcoholic Republic an American Tradition, notes that alcohol consumption peaked at over five gallons per person in the early 1800s as contrasted with approximately two gallons in 1970. A significant drop occurred in the 1840s and the rate stayed around two gallons going forward.2 Earning extra income from the sale of liquor, in his letter of 6 May 1843, E.W. Holmes the commander of the Marine guard mentions two white women “Mrs. Jones and Mrs. Montgomery and others…” for selling liquor on the base to both whites and blacks. Such sales were highly profitable, though Navy barred store owners from selling to slaves and enlisted men, these regulations were rarely enforced.3

1 Clavin, Matthew J., Aiming for Pensacola Fugitive Slaves on the Atlantic and Southern Frontiers (Harvard University Press: Cambridge, 2015), pp. 86-87.

2 Rorabaugh, W. J., The Alcoholic Republic an American Tradition (Oxford University Press: New York,1979), pp 8-9.

3 Clavin, Ibid. p. 87.

U S Navy Yard Pensacola

May 6, 1843Sir,

In obedience to your order of the 5th instant – I sent for Mrs. Jones, Mrs. Montgomery and others, and after making a strict examination into the charge against Mrs. Jones for selling spirits to Steward and Johnson, and for which she was ordered to leave the vicinity of the Navy Yard where she resides. I find the testimony of Sergeant Lorimer that it was upon the information of Mrs. Jones that he was upon the alert and detected those men with spirits, and upon the one occasion he caught George Washington upon the same information. The Negros are in the habit of going to town in small groups during the night – and I believe that to be the source from which they obtain their spirits. I am Sir,

[Signed] Very respectfully your obedient servant

E.W Holmes, CommanderTo: E.A. Lavallette

Commandant Navy Yard Pensacola* * * * * * * * * *

Note: The following letters from of the Pensacola Navy Yard Commandant, Captain E.A. Lavallette, were written to the Secretary of the Navy requesting a decision with regard to Orderly Sergeant Henry Lorimer, USM.4 Sgt. Lorimer was accused by Samuel Glass, a carpenter at the Navy Yard, of breaking into his house and “did go to the sleeping quarters of a negro girl in the employment of said Glass by previous arrangement with the girl, for the purpose of sexual [relations].” 5The letter does not state if the woman was enslaved or free, though it noted a “previous arrangement.” A second document accompanied the letter, this by G.W. Hauvnoy a watchman, at the Navy Yard, and recounts that in September and October of 1842, Sgt. Lorimer had done something similar. Throughout the South blacks, enslaved and free, could not testify in court against whites.6

4 Henry Lormer, Orderly Sergeant, USMC, enlisted16 November 1835. U.S. Marine Corps Muster Rolls 1798 -1892, Roll17 1837, the 1843 roll, enumerates Sgt. Lorimer as Orderly Sergeant USMC Pensacola Navy Yard. Despite the serious nature of the allegations, Sergeant Lorimer continued serving and remained on the rolls of the Marine Corps until at least January 1848 when a muster roll for Brooklyn Navy Yard states, he was again transferred to Pensacola Navy Yard.

5 Samuel Glass, the 1860 U.S. Census, for Pensacola Florida, enumerated Samuel Glass as age 42, living with his family in the village of Warrington. He was born in England, and his occupation in 1860 was listed as carpenter.

6 Garvin, Russell. “The Free Negro in Florida before the Civil War.” The Florida Historical Quarterly, vol. 46, no. 1, 1967, pp. 1–17, accessed 6 Oct 2020.

U S Navy Yard Pensacola

July 28th 1843Sir,

I have received your communication of this date in which you state that, “Agreeably to your note of the 25th instant, in which now enclosed a letter of complaint from one Samuel Glass. I have investigated the subject matter of the complaint against Sgt. Lorimer and find the facts to be that Sgt. Lorimer did go to the sleeping quarters of a negro girl in the employment of said Glass by previous arrangement with the girl for the purpose of sexual [relations]. The offense of the Sergeant, in a military point of view, is his leaving the barracks at unreasonable hours without express permission, for this I have rebuked him severely and imposed restraint upon his liberty which I should otherwise have thought necessary, and have the satisfaction to see that he feels the punishment and have the assurance also that he will not repeat the offense.

A partial apology for his taking the unwarranted liberty may be found in the fact that [he] has frequently been left in charge of the barrack and been accustomed to exercise his discretion, in as to the time of absenting himself, and he does not appear to have thought that in this instance he had transcended the proper bounds of Orderly Sergeant. As to the offense of adultery with the negress if it was committed (which is not prove[n]) is an offense against the laws of the land and is not necessarily cognizable by military authority and discipline. In my investigation in this case, I am well appraised that no harm has been done under this head, but as much as may have been perpetrated in the sight of Him who sees the secrets of men’s hearts as well as actions and although I have not failed to contain the Sergeant as to his conduct in this particular in future and to point out to him the scandal of his crime, still I cannot but feel convinced from what I know to be the prevailing state of morals in the South and from what I am appraised, he has often witnesses that he has at least the shadow of apology for not [illegible] upon the crime in one of the most heinous of guilty nature. I hope you will approve of my proceeding in this affair."

So far from approving of your process in this affair, this meets with my unqualified and decided disapprobation.

The complaint in this this case was laid before me as commanding officer of this station by a certain employee who is employed in the navy yard as a mechanic, who lives in the public ground in the community which in some degree comes under the control of the commanding officer of the station, and which looks to him for redressing grievances coming properly under his supervision and authority.

I regard the charge preferred against Sgt. Lorimar, as one of very serious character, the accused being a noncommissioned officer of the Marine Guard doing duty on the Navy Yard under my command. I enclosed the letter of complaint to you with an order to have “a strict investigation made and report to me in writing all circumstances of the case as they should be proved.”

In this process you were not to inflict punishment but to collect the facts and elucidate the merits of the case; neither does the complainant charge the accused with any violation of military duty, but with the offense of breaking into his house and of committing another of the most gross sensuality.

I might well imagine the state of mind in the vicinity of the navy yard to be coarse indeed, if the complainant, who is represented as a respectable man, could be satisfied with a mere rebuke being administered upon the Sgt. for an offense of so grave a character and reflecting so much scandal upon his family .

The circumstance of the accused “having been left in charge of the Barrack and accustomed to exercise his discretion as to the time of absenting himself,” so far from palliating only aggravates the offense, as a better example should have been offered by, and certainly was expected from him, than from a private kept under greater restraint.

As to the example from you, “which you think might give the shadow of apology for not looking upon the crime as one of the most heinous and guilty nature,” I must affirm that in the course of twelve months, which owing the whole period of my command at this station, I have never known or heard of an example which could lend me a moment to believe that the morals of this community were not equally good with those of any other.

Be that as it may, however, the example of a crime gives me not the shadow of an apology “to another who commits it.” Mr. Glass and his wife both positively assert that they saw the Sergeant in the sleeping room of the negress, asleep. The verification of these facts alone give sufficient reason to justify the infliction upon the sergeant of the severest form of punishment. I must therefore direct that the sergeant be suspended from duty and confined to the limit of the garrison until the Secretary of the Navy may handle this case to whom I will transfer Mr. Glass’s Statement and allegation of the circumstances.

I would have decided at once on this case and ordered Sergeant Lorimar to be reduced to the ranks, but my view of his offense seemed to differ so much from the officer, that I determined to lay the matter before the Department for its decision.I am Sir, Very Respectfully your most obedient servant

[Signed] E.A. Lavallette7To: Capt. John G. Williams

Commanding Marine Guard

U.S. Navy Yard Pensacola7 Elie Augustus Frederick La Vallette (1790–1862) was born in Alexandria Virginia to a distinguished and wealthy family. He later changed the spelling of his surname to Lavallette. He served as commandant of the Pensacola Navy Yard from 1842-1846. Lavallette was a hero of the Battle of Lake Champlain, where the British were defeated in a decisive engagement of the War of 1812. Lavallette distinguished himself during the battle, winning promotion and a medal. He received his commission as lieutenant on December 9, 1814. Lavallette was promoted to the rank of Captain in 1840 and to Rear Admiral by Abraham Lincoln shortly before his death in 1862.

U.S Navy Yard Pensacola

June 15, 1844Sir,

I beg leave to draw to your attention to two letters which I addressed to the Department on the 29th of July 1843 with their accompaniment relative to the bad conduct of Sergeant Lorimer of the Marines, and to state that the matter appeared to have been referred by the Department to General Henderson, as an order was soon after received from him directing his discharge or exchange as the option with anyone of his rank on board any of the vessels. He did not succeed in effecting exchange and was discharged at the expiration of his time of service which occurred a few months after when he left the station.

A day or two since Lorimer again returned with the order of General Henderson to report himself for duty, and must believe the circumstances that General Henderson has forgotten under which the Sergeant was sent from this station or he would not have ordered him here again. I feel assured that I have only to bring the circumstances of his case with additional notice of his actions by the inhabitants of the vicinity to the notice of the Department, and to state that the enclosed communications are both expressions of the opinion & feelings which influence almost all persons residing within and without the walls of the Navy Yard, to obtain the proper & immediate action of the Department in this matter by his early removal from this station.

I have the honor to be very respectfully your obedient servant.

[Signed] E.A. LavalletteTo: the Honorable Secretary of the Navy, Washington D.C.

Attachment 1:

Warrington Village, on the U.S. Navy Yard Pensacola

June 15, 1844Sir,

I regret exceedingly to learn that Sergeant Lorimer, formerly attached to the Marine guard at the Navy Yard under your command, and dismissed for his infamous conduct in this neighborhood last July (of which as related by myself & family I made a correct representation to you at the time, and also laid before my affidavit of the same about the 29th of July) has returned & reported for duty again upon this station. We are once more exposed to the annoyance of his designing & propensity, and consequently have deemed it my duty to call your early attention to this fact, and request the exercise of your influence & authority to protect us & our family from the insults & vile misconduct of Sgt. Lorimer, by if possible procuring his removal from this station or at least by placing him in a situation to prevent the indulgence of his evil doing.

I am Sir very respectfully, you’re most obedient servant.

[Signed] Samuel Glass

To; Captain E.A. Lavallette

Commanding U.S. Naval Station PensacolaAttachment 2:

[Statement]

I was compelled to discharge a woman, a woman whom I had hired as my cook in the month of October 1842, on account of the conduct of Sgt. Lorimer who came to the bedroom of my cook night after night in the month of Sept & Oct 1842, to the great annoyance of my family and the neighborhood. I have been called on frequently by a negro man, James Adams, belonging to Mr. George Willis, who lived in my kitchen at the time to come and witness the conduct of Lorimer, but on account of his being a white man and to prevent any further instances of his vile conduct, I discharged the woman on the 18th day of October 1842.

[Signed]

G.W. Hauvnoy[Captain Lavallette‘s note], “Watchman in the Navy Yard, but residing outside the walls”

* * * * * * * * * *

Note: This letter refers to Daniel Saint, the sutler for the U.S. Marines. Daniel Saint was born in Pennsylvania and is enumerated on the 1850 U.S. Census as 50 years of age with his wife Louisa, age 38, and their three children. A sutler or victualer is a civilian merchant who sells provisions to an army in the field, in camp or in quarters. Sutlers sold wares from the back of a wagon or a temporary tent, traveling with an army or to remote military outposts. Sutler wagons were associated with the military, while chuck wagons served a similar purpose for civilian wagon trains and outposts. Sutlers, were frequently the subject of complaint as they were often the only local suppliers of non-military goods on U.S. Marine and Army posts and often developed monopolies on commodities like tobacco, coffee, or sugar and rose to powerful stature. The 1850 census reflects that Daniel Saint and family lived in the town of Pensacola.8

8 Chisholm, Hugh, ed. "Sutler". Encyclopedia Britannica (11th ed.), (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge England, 1911), p. 171.

U.S. Navy Yard Pensacola

29 July 1844Sir,

I herewith transmit a communication from Mr. D. Saint and have to state that Mr. Saint has never been officially reported to me as lacking conciliatory manner or a want of disposition to accommodate the Marines to whom he is sutler. Mr. Saint informed me on moving to Pensacola that he has never been ejected from the house, which he occupied with his family, and as his store, by Capt. Williams and he was in consequence obliged to move them to town. I have the honor to be very respectfully your obedient servant.

[Signed] E.A. LavalletteTo: the Honorable John Y. Mason,

Secretary of the Navy, Washington D.C 99 John Young Mason, 1799-1859, was appointed the 16th United States Secretary of the Navy in the Cabinet of President John Tyler and served from March 14, 1844, to March 10, 1845, and again as the 18th Secretary in the Cabinet of President James K. Polk from September 9, 1846, to March 7, 1849.

* * * * * * * * * *

Note: “A Painful Disaster”

A sailors life was always dangerous. This tragic accident occurred in Pensacola Bay on Monday, 28 October 1844, when a small cutter from the USS Falmouth (possibly overloaded) with sixteen men aboard, overturned in a freak wind. Due to the weight, configuration of the boat and the collapsed sail, it proved impossible for the men to right the craft. Most drowned after clinging to the hull until overcome by the cold water and exhaustion. The dead were later listed as: Lieutenant Ferdinand Piper USN, Professor of Mathematics William S. Fox, William Dixon, Hugh Toner, Joseph Huff, Ordinary Seamen, John W. Cappo, Landsman, and William Wyatt and William Torrington, Boys all of the U.S. Navy ship Falmouth .10 The survivors were rescued by the schooner Otter. The Sloop of War USS Falmouth operated chiefly in the Gulf of Mexico as part of the Home Squadron and was frequently in Pensacola. Most nineteenth century sailors could not swim. “Everyone who enters the U.S. Navy today must pass a Navy Third Class Swim Test. ... The Navy does offer remedial swim training to those not accustomed to swimming, but this is often during any "free" time the recruit or student may have.”1110 “Painful Disaster - Drowned by the upsetting of a Boat in Pensacola Bay on Monday P.M. on the 28th October 1844” The Charleston Daily Courier (Charleston, SC),1 May 1844, p.2

11 The Balanced Careers, https://www.thebalancecareers.com/navy-swim-test-qualifications-4056770

U.S. Navy Yard

Pensacola November 2, 1844Sir,

I have the painful duty of transmitting to you the communication from Commander Sand relating to the loss of Lieutenant Ferdinand Piper, Mr. William Fox, Professor of Mathematics, four seamen and two boys belonging to the U.S. Ship Falmouth by the upsetting of a boat. This melancholy event has cast a gloom over us all, Lieutenant Piper having endeared himself to all who knew him, all greatly lament this sudden dispensation.

I have the honour to be, very respectfully your most obedient servant.[Signed] E. A.T. Lavallette

To the

Honorable J. H. Mason

Secretary of the Navy

Washington D.C.* * * * * * * * * *

U.S. Navy Yard Pensacola

January 5, 1845Sir,

I beg leave to call the attention of the Department to letters which I addressed to it on the 15th June and 30 last, accompanied by a communication from one of the inhabitants of the village adjoining the Navy Yard, relative to the misconduct of Sergeant Lorimer; the Sergeant has continued to remain here ever since waiting the decision of the Department in his case. I also respectfully call to the notice of the Department Sergeant Montgomery Carter, of November 6th and hope its decision will be given to both cases that these men may be disposed of.

Sergeant Montgomery is an old man and I think if he is reduced to the ranks for his offense without corporal punishment it would be sufficient, there being reason to believe that Boatswain Crocker was also intoxicated in the incident of their difficulties and which may have led them to it therefore. I have the honor to be very respectfully your obedient servant.

[Signed] E.A. LavalletteTo: the Honorable John Y. Mason,

Secretary of the Navy, Washington D.C* * * * * * * * * *

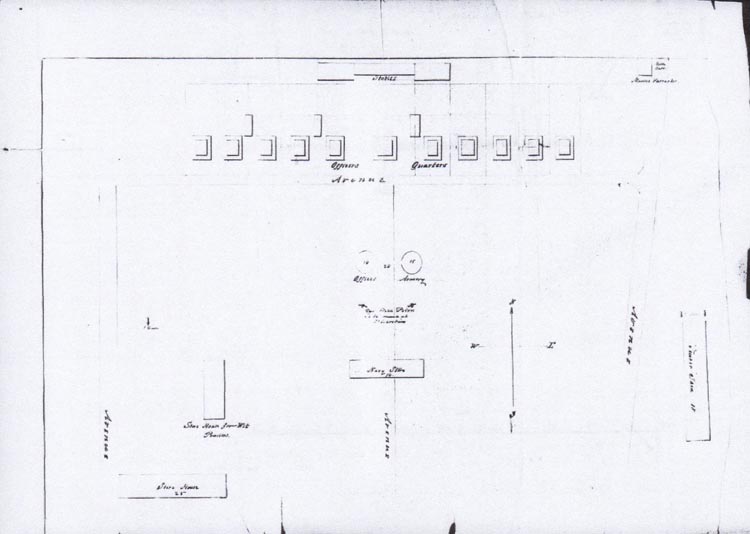

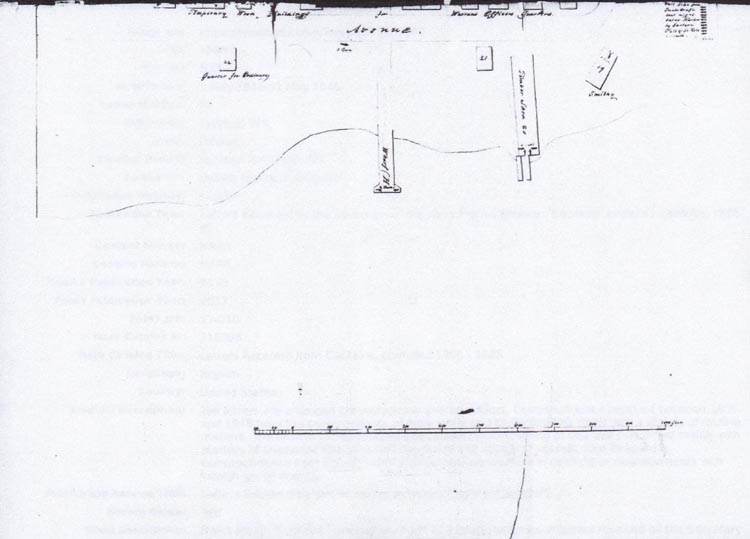

The 9 May 1846 map of Pensacola Navy Yard provided to the Secretary Bancroft to show the location of the marine barracks, warehouses and perimeter walls.

Note: The Mexican-American War began on 25 April 1845. Florida, though supportive of the war, was apprehensive and fearful of a full blown slave revolt and many of its citizens believed rumors and tales of impending slave insurrections.12 The heightened state of alarm and distrust among slaveholders, that Mexico might invade, led to demands on the Department of the Navy for arms and ammunition and nightly militia patrols to monitor all movement of Pensacola’s large black population. The 1844 trial of abolitionist Jonathan Walker (1799-1878), at Pensacola was widely followed. Walker quickly became known as "The Man with the Branded Hand” when he was sentenced as a slave stealer for his attempt to help seven runaway slaves find freedom. As punishment Walker was sentenced to a heavy fine and branded on his hand by the United States Government. His brand was inscribed with the markings "S S" for "Slave Stealer".

12 Commodore William K. Latimer USN was born in Maryland circa 1796 and entered the navy on 15 November 1809 as Midshipman, promoted as Lieutenant 4 February 1815 and Master Commandant 2 March 1833. He commanded the Pensacola Navy Yard in 1837 and was promoted to Captain 17 July 1843. From 1846 to 1847 he again commanded the Pensacola Navy Yard. He entered the Reserved List 13 September 1855 and was promoted to Commodore on Retired List 16 July 1862. He died on 15 March 1873 in Baltimore, Maryland.

In his letters (see particularly 20 May 1846 to Secretary of the Navy George Bancroft Latimer) he acknowledged that “I found a plan was in contemplation by them, the prompt and timely steps taken to arrest its progress has no doubt defeated their object”. He then informed Bancroft, about the local situation and what precautions had been taken to secure Pensacola City, the Navy Yard and hospital and to allay fears of local slaveholder of a general insurrection.

Note: In the U.S. Navy, desertion was a serious offence and accounted for nearly three quarters of all court martial convictions. At Pensacola the desertion of enlisted men like Private Smith remained a critical problem throughout the antebellum era (see 15 and 16 September 1836 for further accounts of deserters. The new Naval Hospital was not completed until December 1835. Because of the high desertion rate, Dr. Hulse repeatedly expressed concern that his patients might be tempted by the local grog shops, hence the construction of large brick wall around the new facility.

9 May 1846

Pensacola Navy YardSir

From information obtained by the City authorities of Pensacola] were informed that a negro insurrection is apprehended there, inconsequence of the large number of Negros employed in the Yard & Vicinity and that it might be I furnished arms and ammunition to the mechanics and others outside the yard and established a nightly patrol and every precaution taken to prevent a surprise and to prevent any attempt that may be made All male whites in the villages and & neighborhood of the yard number over 100 those inside about 50 or so.

I feel perfectly secure should an insurrection occur among the Negros in this immediate vicinity I have requested of Col. Crane, Military Department the loan of three pieces of field artillery.

I have the honor to be very respectfully, Sir, your most obedient servant.[Signed] W. K.. Latimer

CommandantTo Honorable George Bancroft

Secretary of the Navy

Washington DCEnclosure, Map of the Pensacola Navy Yard, showing the stores, officers’ quarters and U.S. Marine barracks

Sources: W.K. Latimer to George Bancroft, dated 9 May 1846

Letters Received by the Secretary of the Navy from Captains ("Captains' Letters") 1805-61; 1866, Volume: 330, 1 May 1846-31 May 1846. Letter Number: 92, M125, NARA WashingtonGranade, Ray, “Slave Unrest in Florida.” The Florida Historical Quarterly, vol. 55, no. 1, 1976, pp. 18–36. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3007130 accessed 8 Oct. 2020.

Jonathan Walker, National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/people/jonathan-walker.htm accessed 9 October 2020

“ Lynch Law in Florida" Pensacola Gazette ( Pensacola, Florida), 24 January 1846, p.1.11 May 1846

Pensacola Navy YardSir

I herewith enclose copies of my instructions to Col. Crane, this copy with my __ of the 6th instant. …In my letter of the 9th instant I explained to you of having asked Col Crane for the loan of three pieces of field artillery for the protection of the Yard. At the request of Surgeon Hulse and in consequence of a supposed outbreak arming the slaves, I have furnished arms and ammunition to the hospital, the number of men able to bear arms being about twenty five or thirty; I have the honor to be very respectfully Sir, your most obedient servant.

[Signed] W. K. Latimer

Commandant.

To Honorable George Bancroft

Secretary of the Navy

Washington DCSources: W.K. Latimer to George Bancroft, dated 11 May 1846, Letters Received by the Secretary of the Navy from Captains ("Captains' Letters") 1805-61; 1866, Volume: 330, 1 May 1846-31 May 1846. Letter Number: 43 M125, NARA Washington

Dr. Isaac Hulse, Surgeon USN http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/nnysharp11.html

20 May 1846

Pensacola Navy YardSir

I have the honor to inform you that since my communication of the 9th instant nothing has occurred to induce apprehension of an outbreak among the slaves in the neighborhood of Pensacola. I found a plan was in contemplation by them, the prompt and timely steps taken to arrest its progress has no doubt defeated their object and the matter seems quiet on the subject.

Precaution and continued watchfulness will I have no doubt entirely arrest any attempt by them of such a measure. Patrols are continued to be reported in the City of Pensacola and in the villages adjoining the yard and every precaution observed. I have the honor to be very respectfully Sir, your most obedient servant.

[Signed] W. K. Latimer

Commandant.

To Honorable George Bancroft

Secretary of the Navy

Washington DCSource: W.K. Latimer to George Bancroft, dated 9 May 1846, Letters Received by the Secretary of the Navy from Captains ("Captains' Letters") 1805-61; 1866, Volume: 330, 1 May 1846-31 May 1846. Letter Number: 92, M125, NARA Washington

Note: In the U.S. Navy, desertion was a serious offence and accounted for nearly three quarters of all court martial convictions. At Pensacola the desertion of enlisted men like Private Smith, remained a critical problem throughout the antebellum era (see 15 and 16 September 1836 for further accounts of deserters. The new Naval Hospital was not completed until December 1835. Because of the high desertion rate, Dr. Hulse repeatedly expressed concern, that his patients might be tempted by the local grog shops, hence the construction of large brick wall around the new facility

30 November 1846

Pensacola Navy YardSir,

I have the honor to inform you that Private Smith belonging to the Marine Guard stationed at this Yard, deserted on the 26th instance. He escaped at night by scaling the Yard Wall in the rear of the Marine Quarters. As the 17th article for government of the Navy under which his offense comes requires that he should be punished by a sentence of a Court Martial and leaves nothing to the discretion of the Commandant of the Yard I should be glad to receive you instructions in the case.

As this is the third instance (two of which have already been reported to the Department) of desertion by means of scaling the Yard Wall, I would respectfully suggest to the Department whether it would have a good effect to punish this man by sentence of a Court Martial that others might be deterred from committing like offence. I shall continue him in confinement until the pleasure of the Department is known. I have the honor to be very respectfully Sir, your most obedient servant.[Signed] W. K. Latimer

CommandantTo: Honorable George Bancroft

Secretary of the Navy

Washington DCSources: W.K. Latimer to George Bancroft. dated 30 November 1846

Letters Received by the Secretary of the Navy from Captains ("Captains' Letters") 1805-61; 1866, Volume: 336, 2 Nov1846-30 Nov 1846, Letter Number:105, RG 260, M125, NARA Washington DC

Pensacola Gazette (Pensacola, Florida), 4 October 1834, p.4.Sharp, John G.M. ,Early Pensacola Navy Yard in Letters and Documents to the Secretary of the Navy and Board of Navy Commissioners 1826-1840, Part II http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/pensacola-sharp-2.html

* * * * * * * * * *

Note. The year 1846 was particularly hard for the Pensacola Navy Yard Hospital, the Mexican-American War, which began in April 1845 meant that the hospital had many casualties, though the worse killer was disease. Newly arrived Naval Constructor James Rhodes had died of yellow fever. In a letter dated 16 November 1846 Navy Yard Commandant Captain W.K Latimer notified the Secretary of the Navy George Bancroft that Mr. Rhodes had “died of a protracted illness.” Naval Surgeon Dr. Isaac Hulse who treated Rhodes and most of the others afflicted tragically lost his eight year daughter to the disease. Including civilians killed by violence, military deaths from disease and accidental deaths, the Mexican death toll may have reached 9,000 and the American death toll exceeded 13,283. In totaling all deaths among American soldiers in the Mexican-American Wa, 1,192 were killed in action, 529 died of wounds received in battle, while 362 suffered accidental death and 11,155 soldiers died from disease. However diseases including yellow fever, dysentery and typhus claimed a toll seven times greater than that of all Mexican weapons.

7 November 1846

Pensacola Navy YardSir

It becomes my melancholy duty to inform the Department of the Death of Mr. [James] Rhodes, late Naval Constructor of this Yard. He died this morning about ten o’clock, from the effects of the fever which prevailed to such an extent at this season. I have the honor to be very respectfully Sir, your most obedient servant.

[Signed] W. K. Latimer

CommandantTo: Honorable George Bancroft

Secretary of the Navy Washington DCSource: W.K. Latimer to George Bancroft. 7 November 1846

Letters Received by the Secretary of the Navy from Captains ("Captains' Letters") 1805-61; 1866, Volume: 336, 2 Nov1846-30 Nov 1846, Letter Number:22, RG260, M125, NARA Washington DC* * * * * * * * * *