MEMOIRS OF EUGENIUS ALEXANDER JACK

Steam Engineer, CSS Virginia

Excerpted from E A Jack's original and edited notes

I find myself at the very beginning of these notes impressed with a sense of their unimportance. For what have I done to make my life otherwise. If I were to pass away this hour, not one thing that I have done would live after me to show that I was more than an ordinary many to any person outside of my family. But as I am writing for that family I will be encouraged, for my failures or successes in life may become beacons to guide my children. I will first give a chart of my lineage and that of my children as far as I can.

Alexander Jack m. John Jack Hannah Lockwood Eugenius Alexander Jack James Atkinson m. Mary E. Jack ____ Hilt Lawrence B. Ege m. Ella B Ege m.

E. Alexander JackLawrence McKay Jack

Eugenius Alexander Jack

Kenneth Hilt JackCaroline M. Ege Wm. Henry Benson m Mary R. Benson

E. Alexander JackRaymond Lockwood Jack Martha Fry Benson In childhood I received the usual amount of cuts, bruises and maladies, was guilty of peccadilloes as other boys and was whipped for them by my ever vigilant parents, most of them deservedly but sometimes undeservedly. I remember of the latter, one given me for fighting. My antagonist was a schoolmate larger and older than myself who provoked the combat. He had tried his strength with mine before and found that the vantage was with him. And like other boys presuming upon the first victory had provoked other contests and found me ever willing to meet him, though never victorious. At last with increase of skill and strength, I whipped him, but unfortunately the fight was seen by mother and no excuse could save me from castigation. Through childhood and boyhood by the help of good parents and home influences, I came to manhood free from any great vices and prepared to escape any future temptation to contract them. If I shall see in my latter days that my boys have profited too by the good influences that have been placed around them as safe guards by those that love them, and I shall have the comfort to know that by either precept or practice my influence has drawn them away from evil on towards good and I shall rejoice in it. If ought that I may have taught them or may write here, shall send them onward and help them to reach distinction and fame, or shall sustain them in hours of temptation and deter them from going backwards to deeds that will cause the hearts of those who love them to bleed with sorrow, I shall then have helped them as my parents helped me.

At the age of sixteen my school days ended. Equipped with such an education as our Public Schools afforded and I was able to receive, I now started out to find an occupation. My first experience was in a dry goods store kept by a Mr. Noyes. After an apprenticeship of one day in which by selling more for credit than for cash, I proved my unfitness. I gave this up and started in the pursuit to which my inclinations leaned. I took place as an apprentice in the Gosport Iron Works. A few months after, by the influence of my uncle Archibald Atkinson, I obtained an apprenticeship in the department of Steam Engineering in the U. S. Navy Yard at Gosport. My ambition from the first had been to become an engineer in the U. S. Navy. This new position gave me much better opportunities to fit myself mechanically for that position than the one I gave up. I was also required to have some engine room experience. This I gained on the Bay Line Steamer Adelaide where I received instructions for a few weeks under Mr. Noah Bratt of Baltimore, Md., who was the Chief Engineer. My time on the Adelaide was limited by the Master Workman at the Navy Yard who would not consent that I should be away from my shop duties longer. But this brief experience satisfied the requirements and through the attendion and instruction of Mr. Bratt I learned enough to show that I had some practical knowledge of the care and management of steam engines. I was now near the last year of my apprenticeship, and returning to my shop duties awaited the call for candidates for the Naval Engineering Corps.

About this time, however, a spirit of hostility between the states north and south began to culminate and whispers of secession and war were heard. Then I saw my dream of service under the stars and stripes begin to fade, for if the war came I must cast my lot with my state and section to which I felt that I owed the most allegiance. I therefore permitted the opportunity - to enter the Navy which now offered to pass, and continued at my trade. Then came news of the secession of South Carolina, the bombardment of Fort Sumter, the call upon the Souther States by the Federal Government for their quota of troops to coerce the seceeding state, the secession of Virginia and the march of Southern soldiers to defend the south from the invading north. War had come - few knew its magnitude or the suffering and death that would follow in its wake. Some hearts were elated and predicted an easy repulse of our invaders, others grieved to see the flag under which the young states had sealed their union and shown their strength torn from its place above us, grieved to see a union which had given so much power already to the states broken and the members and warring with each other. These spoke of hand fought battles - for Americans were brave wherever born - and privations and perhaps defeat. But all with one spark of patriotism came forward to offer their bodies as a shield to the Commonwealth or in support of the Federal Union. And so I, not then quite a free man, enlisted in the "Old Dominion Guards" Co. K. 9th Va. Regiment.

Troops began to arrive from the states south of us, and the Federal forces who held the Navy Yard becoming alarmed at the concentration of forces so near them gave up what Government property they could not destroy or take away and left the yard. That which they had left was very acceptable for there were great guns and machinery to be used to refit them for use. These the Confederate forces appropriated and began to use to equip themselves to meet the enemy should he attempt to return. Some of the guns after being unspiked were mounted in battery around the harbor. Others were sent to the front to defend our frontier along the Potomac and other rifled and strengthened to conform to modern ideas of ordnance.

Our company was mustered into service and placed in quarters at the Naval Hospital. Citizens and soldiers were busy throwing up breastworks for a battery on that point to defend the Fort from the enemy who we could hardly believe would not attempt to repossess themselves of the valuable position they had so easily given up. The "Pawnee" was the "bug-bear", for some reason that vessel was the most dreaded though there were others of much greater armament. Everybody had the "Pawnee fever". One night we were called to arms by the "long roll". In the haste to equip ourselves, a gun was discharged and Lt. Henry Allen was slightly wounded. The dreaded enemy did not appear though and we went back to our blankets, many of us too full of excitement to sleep more that night.

There were days of drilling and discipline of grand rounds and guard mounts and yet after all we were only playing soldiers then, as those who went to the front afterwards and met bullets and privations found out. Our officers sought in many ways to teach us vigilance, and were were often found lacking in the quality which soldiers should preserve, but were let off with reprimands or light punishment for first offenders.Some of the ways used were so persuasive. A group would come up to a sentinal and ask his opinion of some movement in the manual of arms. He would make it for them and then one would say that is wrong. Another would say its right, and then another would day "it is this way" and attempt in an offhand way to take the gun from the sentry to illustrate his method. But woe to the soldier that gave up his gun when on post, for a reprimand or punishment would certainly follow and his companions would have the laugh on him for some time or until another was caught the same way,

From the Hopsital our company went to Pinners Point. There was more work digging dirt and mounting heavy guns and preparing for winter quarters. Soon after our arrival I reached manhood. It seemed to me that to spend this day of all others in camp under military restraints was altogether inappropriate. How could I feel like a free man when I had no freedom. So I asked furlough for that day boldly saying that it was my 21st anniversary and that I wanted to feel like I was free. It was hard though to persuage Capt. Harrison, C. S. N to let me go for our company had annoyed him very much by its insubordination to his old navy ideas and had been disciplined a little for it. But after some thought he said, "I can't give you liberty, but I will send you on duty." So he sent me away on an errand with instructions to be back the next morning, with further instructions not to spend much time on the errand if I found it difficult to find the thing that he wanted. It was a book of some kind. I don't think that the old gentleman expected me to find it at all. I suppose he felt indulgent towards me although he could not forget the pranks that our company played on him. When a crowd of men live together away from the modulating influence of pure women, their bent seems to be to fun or fighting. I am glad that our company did not follow the latter among themselves, though they had plenty of that quality for the enemy. Their bent took the former turn and practical jokes were the order of the day. One joke gotten off at the expense of an officer who was an M.D. I will relate. An order had been issued that we shoud not molest private porperty or the stock of the farmers in our neighborhood. But one day a flock of ducks came into our camp and Sargent L could not resist the temptation to toss a ram rod at them. One of them was impaled and the Sargent was called to explain his disobedience of orders and said, "I have great respect for my officers and their commands. That duck passed right in front of Lieut. ___ and called him Quack! So he died for I could not stand by like a coward and hear an officer insulted."

As I was familiar with the bypaths around our camp, it was an easy matter to pass the pickets and get to town, and others did so too. Once our absence was discovered and a sergeants guard was sent into town to arrest us. By a little diplomacy we got them under our control and marched by the picket with the countersign. They were in our power and could not report us, so we escaped punishment.

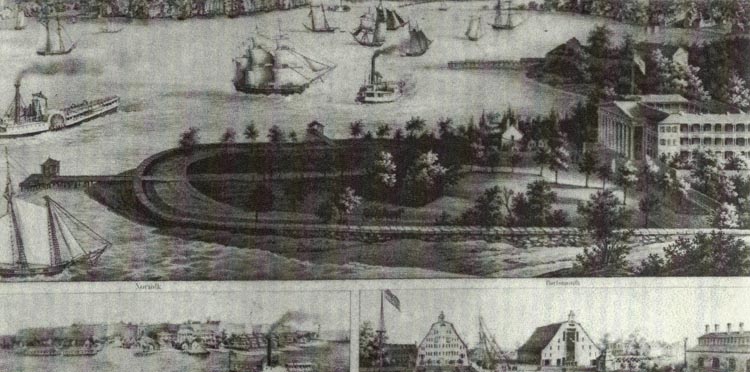

View of Norfolk and PortsmouthThese were the happy days of soldiering, and yet we grew restive. The war had begun in earnest. Within our state and nearly at our door the battle of Big Bethel had been fought. This aroused the war spirit of the O. D. G.'s and they applied for more active duty and were almost mutinous when the application was denied, although a promise that they would get all the active service that they wanted came with the disapproval to their petition. They did too and I was not a little amused when sometime afterwards I met some of them to find that their ardor had decreased in proportion to their accumulation of dirt and rags. They then had enough of war, but those who escaped the bullet and the hospital fought the hopeless fight for three years longer.

Before the company went into winter quarters, I was detailed to duty in the Navy Yard at Gosport and put to work at my trade. This was quite a financil promotion to me, for the wages of a private soldier was, I think, $16 per month. My wages as a journeyman machinist was, although just out of an apprenticeship, over $60 per month. This was more than the Captain of the company was receiving for his military services. There was lots of work in the shop and machinists were in demand as was evidenced by my having been detailed to this duty without my application or even desire, for I was full of the military spirit and preferred the more honorable though less lucrative position of soldier.

The "Merrimac" which the Federals had left burnt and sunken had been raised, and preparations were made to convert her into an ironclad to be used against the enemy who still held Hampton Roads and the mouth of the James River and threatened us at all times.

My ambition to become an engineer was aroused, so I determined to make application for that position in the Confederate Navy and hoped that I might be ordered to her, therefore I sought opportunities to make myself familiar with her machinery. But much work had to done on her yet. I therefore delayed my application. In the interval I became interested in pyrotechnics and used to spend my unemployed time watching the preparation of shell fuses and other ordnance equipment that was made in the small laboratory that had been fitted out in the Navy Yard. Their methods were very crude. In making the fuses they put small quantities of the compound in the fuse shell and then it was hammered down. The judgment of the workman had to be relied upon to get it in uniformly compact. The consequence was that these fuses were very unreliable and burned so irregularly that the explosion of a shell could not be accurately timed. This work was done by delicately adjusted machinery in better equipped works, but no one knew the mechanism. A hint from a shopmate started me to thinking of it, and between us we got up a plan for a machine to do the work. There were others in the shop thinking on this same idea, but my friend Mr. James Jordan and myself got ahead of them. I prepared the drawings and they were submitted to the commander of the yard. He detailed us to go to Richmond, Va., with our plan, and also directed us to acquaint ourselves with the methods and machines for making percussion caps that were obtained at the laboratory at that place.

Our plan was approved by the Chief of Ordnance at Richmond and the department ordered one of our machines to be built. This machine consisted of a sleeve threaded on the outside and wheeled at the top to be moved up or down through a boss which was supported by two legs resting upon a strong bedplate. Through the sleeve passed a shaft which projected at both ends, the lower end carrying the mandril which fitted the fuse shell, the upper was acted upon by a system of levers that exerted a pressure of, I think, two thousand pounds. The shaft was held in this sleeve by a key passing through both sleeve and mandril, fitting tight in the latter. But the slot in the former was made long enough to permit the shaft to have an upward motion through the sleeve though the sleeve should be moving oppositely. By this arrangement, when the plunger or mandril came in contact with the fuse compound it compressed it until the resistance equaled two thousand pounds, or whatever pressure the levers were loaded to. Then as the sleeve continued to go downward and carry the lever mechanism with it, the shaft acted upon the levers and they, altering their normal position, struck an alarm bell which indicated that the required pressure had given the fuse. The wheel was then turned the other way and this mandril was ready to be entered into another fuse shell or to be used on another charge of the composition. I believe that it was practicable although the lever arrangement was complicated, but if they had not been satisfactory we contemplated using hydralic pressure.

Our machine however was never built. Before it was fully completed this section of Virginia was evacuated and the United States Government again took control. Possibly some better machine was imported through the blockade, for our machine was left in the hands of the enemy, drawings and all. I was written to about it once afterwards, but I suspected that the writer wanted it for his own profit and refused to give him the plan until I knew more definitely what he was going to do with it, and that ended the matter.

The "Merrimac" was now so far advanced that we could form some idea of what the fighting machine would look like. The sloping framing of her armor backing was in place, and the workmen had begun to put the iron plates in place that were to form the shield. These plates were of the proper length about 8" wide, I think, and at first one inch thick; afterwards they were made two inches thick. The thinner ones were criss-crossed on the sides of the shield to make up the four inches, the required thickness, and where they gave out the thicker plates were used. Around the forward and after part, I think the thicker ones were used exclusively. They too were criss-crossed in two layers. I am disposed to think that the rolling mills at Richmond were not at first prepared to make plates thicker then one inch or the thicker ones would have been used altogether so that the shield might be as strong as possible. What an insignificant thickness this four inches of iron appears now to our ponderous shields of thirteen and fifteen inches of hardened steel. And how small our six and seven inch rifled guns, fifteen or less feet long, appear beside the monsters of this era carrying projectiles averaging a ton or more, and projecting from breech to muzzzle more than twice that length, and casting their heavy shot or shell five times as far as our pigmy pieces could. Wonderful that from so small a gun these great guns and armors have grown.

I now thought it was time to make my effort to get an appointment in the Confederate Navy, and duty on her if possible. It was probable though that if I got my warrant as engineer I would be ordered to the "Merrimac", for I had been working on her engines and the desire of the Government would naturally be to put those in the engine room of whom most might be expected. I made my application through Chief Engineer Williamson and in due time was fortunate enough to receive my warrant as Third Assistant Engineer in the C. S. Navy, and to be ordered to the "Merrimac" now called the "Vinginia", that except in official communications ever was called by the former name. Taking the oath of office, I assumed my duties, and was invested with authority now to direct those who had but a day before been my directors. However I did not, like some people I have met, use this power to the annoyance or humilitation of anyone, but let things go along pleasantly, taking advice as before from those who had been my advisors and scrupulously performing whatever duty I was instructed with, without arrogance or ill feeling.

The epochs of our lives come upon us unknown. We look upon this as a pleasure which is in fact but the blossom of bitter fruit, which we cast away as dross, which - did we know it, is the sparkling gold in the mask of rock. Truly we know by the lamp of experience, the gold and the dross, the bitter and the sweet in our past actions, but they, like the evils that escaped Pandora, cannot be recalled. They float before us, transformed by the light of knowlefge into beautiful irridescence. If we try to repossess them, we are but overwhelmed by mist and clouds. I, writing now, see in this step the second epoch of my life: the first, casting aside the opportunity to enter the United States Navy. Had I taken the path that led in that direction, profit and comforts that I shall never gain would have been the sequence. But do not suppose that I regret this loss or that I would have acted differently had the failures of the future been revealed to me. There was more than porfit or comfort at stake, there was honor. I had now reached the second epoch, and I entered the way that was to carry me through visissitudes, suffering and defeat, into the hedged and rugged road from which I could never depart.

When I gave up the position of journeyman machinist for one of rank and authority, I seemed to have launched my bark in propitious weather. But the clouds fell and the current grew and carried me on through rocks and eddies of disaster until the gulf was reached where it and all others, launched in defence of honor and principle, were swallowed up in defeat.

All was hurry now to complete the "Virginia", for news came from the North that these people knew of the fighting machine we were building and were erecting one to meet us from plans furnished by the celebrated engineer Erricson and that it was rapidly approaching completion. Vague rumors of its character gave us some idea though that this antagonist would be no mean one, and rumors too were floating around that our vessel was a failure already, that she would not float under the heavy armor even without her guns. This was good news to the enemy if they heard and believed it, but many patriotic southern hearts grew sad at it. The time at last came when it would be seen whether our ship would rise from her keel blocks or lie irresponsive in the encroaching waters which would soon be let into the dock upon her. Many gathered around the dock to witness the ordeal, some with hearts heavy with fear and some jubliant in perfect confidence of success, and others with black traitorous hearts filled with the hope of a failure. But she rose up upon the waters and the shouts of patriots filled the air, and the traitors slunk home and told the enemy that the dire ship had floated and would harrass them ere long.The ship was taken from the drydock and brought to the wharf where by means of the heavy shears her guns were placed in position, and then her shield was completed. But the decks projecting beyond the shield were still above water. These were covered with pigiron until submerged, and a false bow of heavy planking put forward to keep the water from curling up the shield into the bow port. Stores and equipment were taken aboard and the good ship was almost ready for the fray. Armed with six nine-inch Dahlgren shell guns and two five-inch Brock rifles on broadside and one seven-inch Brock gun forward and aft, with her cast iron ram projecting away from the stem about six feet under water and protected with her smooth shield of iron plates, she was no mean-looking machine.Her motor power was two horizontal condensing engines which were supplied with steam from four Marlin boilers containing three furnaces each. The engines operated by link-gear which was shifted by the arc and pinion movement and were quite difficult to manage and required at least two men at each reversing gear. For one of the furnaces, a frame of wrought iron was made upon which shot for the smooth bore guns could be placed and heated and tool and trivets were supplied to handle and carry them to the guns. There were two auxillary steam pumps of the Worthinton type with about six-inch water cylinders. These pumps could be used either to supply the boilers with water or to pump water from the bilge.

She was a curious-looking craft. The sloping sides of the shield sinking below the water about two feet and inclining upward pierced with gun ports looked like the sloping Mansard roof of a house, but a sight of the black-mouthed guns peeping from the ports gave altogether different impressions and awakened hopes that ere long she would be belching fire and death from those ports to the enemy and crashing into their wooden vessels with that formidable ram, sending them to the bottom. But one thing appeared against her effectiveness, her immense draught of water, over twenty feet, would keep her to deeper channels and let the lighter vessels escape her.

Before the vessel was completed, the crew was shipped and drilling was a daily occurrence. There was no difficulty in finding men, for there were many old salts around Norfolk and Portsmouth ready and glad to go in the great ironclad, and of landsmen there were many volunteers from military companies garrisoned around. Many of the United Artillery were among these and they were very desirable men because of their military training. I suspect that many had to be declined though. As my position was subordinate, I do not know this. Then three hundred or more men had to be brought under discipline and instructed of their duties. But of the corps of officers, with only a few exceptions, had been in the United States Navy and were therefore equal to the requirements of their position. I think that Mr. E. V. White and myself, 3rd Assistant Engineers, were the only ones who were from civil life. This officer had been appointed from the machine shop like myself, but as his warrant was later than mine, I was his senior. It would be well to give now the names of the officers. I wish that I had a list of the crew also. Mr. White was fortunate enough to have one.

Captain Franklin Buchanan lst Lieut. & Executive Officer Catesby ap R. Jones Lieut. C. C. Simms at Bow gun (7" Brock) Lieut. Hunter Davidson at guns 2 & 3 Lieut. John Taylor Wood at steam guns (7" Brock) Lieut. John R Eggleson at guns 4 & 5 Lieut. Walter Butt at guns 6 & 7 Capt. R. T. Thom., Marine Corps at guns 8 & 9 Midshipman H. H. Marmaduke at gun 2 Midshipman H. B. Littlepage at gun 4 Midshipman R. C. Foute at gun 6 Midshipman W. J. Craig at gun 8 Midshipman J. C. Long at powder division Paymaster Jas. A Simple, Comd'g at powder division Capt. Kevil , United Artillery at gun 9 Surgeon D. B. Phillips Asst. Surgeon A. S. Garnett Captain's Staff Flag lieut. R. D. Minor Aid. Actg. Midshipman Roots Lieut. D. Forrest, C.S.A. Clerk A Sinclare, Jr Chief Engineer H. A. Ramsey 1st Asst. Engineer John Tynan in engine room 1st Asst. Engineer Loudon Campbell in engine room 2nd Asst. Engineer Benjamin Herring ? in fireroom & in charge of auxillary steam pumps 3rd Asst. Engineer E. A. Jack in firefoom 3rd Asst. Engineer E. V. White at the bell to signal to the engine room Boatswain Charles Harker Gunner Charles Oliver Carpenter Hugh Lindsey Pilots Actg. Master Parrish Pilots Actg Master Wright Pilots Actg Master Clark Pilots Actg. Master Cunningham These are they who went down into the memorable battles that caused the revolution in methods of naval architecture. The features of the two ironclads that rained shot and shell upon each other on the 11th of March 1862 may be found in most of the fighting vessels of the present age.

After a while every preparation that could be made without great delay to the vessel was made, and orders came to proceed to the attack upon the vessels in Hampton Roads. So in the morning of the 10th of March we got steam and left the yard and steamed down the river for the fray. We were without shields for the port holes and solid shot for our rifle pieces. I do not know but that the latter were an afterthought. These things could not be waited for, as the Monitor was expected to arrive and we wanted to get in the field first. Ploughing the water which curled up upon her shield in caressing waves, she looked a formidable craft. The multitude, gathered on the wharves and house tops along her way between the two cities cheered lustily. The tearful, sympathetic women waved their handkerchiefs in Godspeed and turned sadly homeward when we disappeared in the distance, distrustful of the fate of the ship and her venturesome crew. The officers grouped upon the shieldtop abaft the smoke stack and the men forward, with hats doffed, acknowledged the salutations of the people ashore with hearts as full of the solemnity and grandure of the occasion as any. Full many a man onboard that ship felt room for sadness in his elated heart when a face or a token of some loved one was recognized among those ashore.

The narrows of the river were passed and away in the distance the hulls of the enemy's squadron began to loom up. The Boatswain piped all hands to muster and I placed myself, touching elbows with my brother officers, in the starboard side of the shield top. The men were arranged in line opposite to us. We knew that we had been mustered to hear the address of Capt. Buchanan before we entered the fight, and all were curious to know how he would meet the insinuations that had been made against his loyalty to the Southern cause. It had been said that after he had resigned from the United States Navy to take arms with the Confederacy, he had petitioned to be taken back again. His address was brief and as well as I can remember about as follows: "I heard when I came to the command of this vessel aspersions upon my loyalty and doubt of my courage and zeal. I promise you that when this day's work is over, there will be no cause for any such unjust suspicions. Pipe down, Sir."

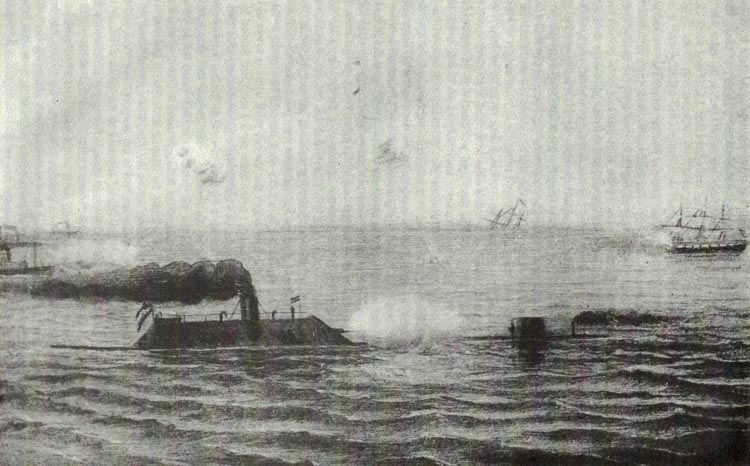

Battle Between VIRGINIA, left, and MONITOR, right.

In Hampton Roads, March 9, 1862The flags of the enemy could now be distinguished. Clustering on the quarterdecks and the forecastles, the officers and men watched the approaching antagonist and measured her strength. Some, no doubt, thought it would be easy work to destroy the thing that looked like a floating Mansard roof with guns peeping through the windows. Others felt the fruitlessness of the fight, but went boldly into it notwithstanding.

Men never fought more bravely or more hopelessly than they did that day. The preparations for the fight now began on our ship and all hands were called to quarters, and I sought my station down in the fireroom twenty feet under water mark with no little anxiety, I confess, as to what the issue would be to this experiment in naval warfare, and not to my discredit a little weak-kneed too. There are few men who do not feel some symptoms of fear when going into battle, pride has kept many a man's face to the foe when his heart would turn it away. In my situation though, if fears had been strongest I had no refuge to flee to. There was no safer place from the enemy's shot than this hole so deep under water. It was the bomb proof of bomb proofs, but I assure you that I would have taken the station of the junior 3rd Asst. on the fighting deck and the risk of shot and shell rather than be so far away from what was going on.

The suspense was awful but it was relieved occasionally by some information through the ash chute that my comrad White would communicate. He would keep me informed of what was going on so far as his observations extended. I knew when the battle had begun by the dull reports of the enemy's artillery, and an occasional sharp crack and tremor of the ship told that we had been struck. But our vessel was responsive.

Soon however I heard the sharp reports of our own guns and then there came a tremor throughout the ship and I was nearly thrown from the coal bucket upon which I was sitting. Thhat was when we drove into the "Cumberland" with our ram. The cracking and breaking of her timbers told full well how fatal to her that collision was. There was at first a settling motion to our vessel that aroused suspicions that our own ship had been injured too and was sinking, but she soon recovered and reversing the engines she was backed away from her sinking victim. A cheer upon the deck and the cry "she is sinking" announced that one of the enemy had been destroyed. Heroic American blood coursed through the veins of the people who were on that fated ship. They fought on still and while hundreds were already in the water struggling for life, and a part of her decks was covered with water, the last gun was fired and she disappeared beneath the waves with her colors flying.

"Give us steam now! All that you can! The enemy is flying," was now communicated to us at the engines and boilers below, so after them we went pouring shell into them from our bow guns and into the forts ashore from our broadsides. Our ships from up the James River had now passed the batteries and engaged with us in the chase. The little "Teaser" with her one gun forward was turning boldly up, and delivered her fire and then ran off until she was prepared for another shot. Now came the news that the "Congress" was ashore, then that the "Minnesota" had grounded too, then through ash chute I was told that the "Congress' had hauled down her colors and that a boarding party had started for her. I do not think that any could have been sent from our ship for they must have been already riddled by the fire through which we had passed. But Lieut. Minor and Mr. John Langhorn (I have forgotten his official position) went from our vessel. Before the prize was reached, the boarding party was met by a volley of musketry from shore that wounded Lieut. Minor and some others. They pushed on though, and boarding the vanquished vessel saw the horrible wreck that we had made of her. Even these men, heated with battle and indignant at having been fired upon under such circumstances, shrank from the carnage that had been wrought. The dead and dying of that brave crew lay piled around their guns, and gaping holes and wrecked guns showed the destructiveness of the shot that had been poured into her. The boarding party did not stay long. A few prisoners were brought off, and then hot shot were fired into the prize which set her in flames. These shot were heated in the boiler furnaces and put in a trivet and hoisted on deck. It was a part of my duty to prepare them.

Night approaching ended this day's fight. I was too tired to stay on deck with my shipmates and watch the revel of the flames on the burning "Congress". Running from mast to mast along the rigging and falling in showers of sparks, the fire was rapidly consuming her. I sought my state room and there on the floor were two of the men who had been killed in that day's action. I did not care much for such roommates, it was too suggestive, so I waited until they were removed to the shore, then sought my berth and was soon oblivious of what I had passed through or of what was to come. I slept soundly, so deeply that I did not hear the explosion of the "Congress" magazine though only a few miles away from her. But the people of Norfolk and Portsmouth, three times as far, heard and felt it too.

This day's fight was directed in its most eventful part by Capt. Buchanan and we all felt now that the impeachments upon his loyalty to the South, or his bravery were groundless. He, with Lieut. Minor, and Midshipman Marmaduke were wounded and three of the men killed. Marmaduke's wound was a slight one in the arm, but those of the Captain and Lieut. Minor were serious. Both though recovered.

When we started into the second day's engagement we were not at all surprised to see our diminutive antagonist, the "Monitor", come out from the neighborhood of the "Minnesota" to meet us. We had been expecting her and although she was said to look like a "cheese box on a raft" we believed that cheese box was as hard to penetrate as our coffin, a name given by some pessimistic mariners to our ship, and knew that these were as gallant men within that circular wall as we had beside our guns, for we had learned from the experience of the first day what little effect the ordnance of our adversaries had upon our iron plate shield. We knew that the "Monitor" had a thicker shield than ours, and that her circular citadel was as effective in deflecting a shot as our inclined sides. Our only hope was in our rifled cannon but as the only projectiles that we had for these were percussion shells, there was barely a chance that we might penetrate our adversary's defence by a lucky shot near the base of the turret or that one should strike it radially. It was discovered after the fight began that the out work conning tower was vulnerable. How nearly our shot came to disabling the vessel though, I never knew until I met Lieut. Samuel Howard of the Revenue Cutter service. He told me that the massive bars of which it was built were nearly dislodged by the shell that blinded Lieut. Warden, and that if this had been driven a "quarter of an inch" further they would have fallen inward crushing the steering gear and the inmates of the conning tower. During this engagement, we were aground for nearly an hour before the "Monitor" selected her position but still failed to do us any material damage. Of course every shot made its imprint on our shield but none penetrated it. One shot struck directly over the outboard delivery, and because that was a weak spot broke the backing to the shield and sent a splinter into the engine room with about enough force to carry it halfway across the ship. When we got afloat we rammed our adversary and shortly after this the engagement ended.

We returned to the Gosport Navy Yard, and the "Monitor", after first retreating to shoal water where we could not follow, returned to the position beside the stranded "Minnesota".

There is a difference of opinion as to which vessel retreated or, to put it differently, first declined fight. The preponderance of evidence is, I think, against the "Monitor" and I have that which makes me say that without a doubt she did retreat. I cannot state it or I would, for it would be a betrayal of confidence. But it is from one who was aboard the "Monitor" and who was in a position to justify what he has told me. But if the "Monitor" was a victor, what prevented her from pursuing the "Merrimac" and destroying her. With her light draught and shield that had proven impenetrable, why could she not have followed us to Norfolk. One writer has foolishly written that she did pursue until recalled, and that she was recalled through fear of torpedoes. Such a fear did not deter the future attacks upon Sewells Point or the advance up the James, the attack upon Fort Sumter or Farragut's advance up the Mississippi or Mobile Bay. With these instances before me, and what I have been confidentially told, I am satisfied that if the world could know what occurred on the "Monitor" after Capt. Worden was hurt, there would be no doubt as to which vessel retreated.

I do not though justify the return of the "Merrimac" to Norfolk on the last day or her return to the anchorage under Sewells Point after the first engagement. There was time enough to have destroyed the "Minnesota" which lay helplessly aground. The reason that I have heard urged in excuse for the action was that we had two officers seriously wounded I do not consider sufficient. We had a full compliment of surgeons on board who were capable of attending to the wounded. Nor do I think the anchorage under the battery at Sewells Point any better than could have been found on the field of action, and as our pilots were of the most intelligent, they must have been competent to guide the vessel at night as well as by day. Why then could we not have stayed on our ground until the last of the enemy within our reach was destroyed. I do not say this because I regret that more carnage was not wrought but only to show the lack of military skill displayed.

On the second day too, after we had tested the mettle of the "Monitor", there was no reason from that time why we should not have taken her fire and given the "Minnesota" ours. Not one of our shells could penetrate her shield and hers fell harmless upon ours. If it was necessary to keep our fire upon her so long as she remained in action, why should we have fallen back within our lines as she declined further action by retreating to the shoal water? Could we not then have finished the work that we had left undone on the first day? I have always thought this movement an unfortunate one, for by leaving the field and returning to Norfolk we gave foundation to the untruthful reports that we were beaten and were in sinking condition, when the truth was that we were as able to continue the fight with any adversary that we had met as ever.

In our school books from which the children of this generation are getting their knowledge of our country's history, this truth is stated in spite of assertions that there is no truth in it from distinguished foreign naval officers, federal officers who witnessed the fight and Confederates who participated in it. These things would never have been written in history if the "Merrimac" had finished the destruction of the "Minnesota" on the second day of the fighting in Hampton Roads. As I was in the fire-room within sight of the steam bilge pumps at all times, in fact sitting by them often, I know that they were not required to do any extraordinary duty and that no alarm about the sinking or leaky condition of the ship was felt in that section of the ship where most would be expected to prevail. But I do not rely upon my own memory of this. I have consulted Chief Eng. Ramsey and Assist. Eng. Tynan, and they agree that there was no serious leaking. Ass. Eng. White has stated differently, but he was on deck and not in the engine or fire room, and got his information there from one of the thousand rumors that prevail in action. In a recent conversation with me he said as much, or admitted that he did not speak of his own knowledge.

I do not mean to deny that the vessel leaked more than when she left port. The shock of concussion with the "Cumberland" first and the "Monitor" afterwards, shattered her stern and started some leaking there, but nothing that would have ever hurried her back to port had she been on an outward voyage. Her bow was heavily timbered up with deadwood to resist such shocks as she had endured. Mr. John Porter who was at that time Master Carpenter of the Yard, I think though afterwards Naval Constructor, says that there was no serious hurt in the bow of the vessel. He also refutes the statement that she was immediately docked. I am satisfied that she was at least one night out of the dock. How much longer I do not know. This is confirmed by the fact that I was permitted to leave the vessel soon after her arrival at the Navy Yard, early enough to attend divine services at the Dinwiddie St. Methodist Church on the Sunday of our fight with the "Monitor". Mr. White also says that he was ashore that night. It is not probable that both the junior assistant engineers would have been allowed to leave the vessel if she was in a sinking condition, for the steam pumps with every other means of freeing the ship would have been required. In fact no officer would have been allowed ashore in such an emergency. Again whenever a vessel of such magnitude was moved, all hands were expected to be at stations, and under such circumstances in view of the extra peril in docking so large a ship, no competent Commander would permit either man or officer to be absent from his post. This to my mind settles the truthfulness of this statement that the vessel was in a sinking condition and had to be hastily docked, if my memory did not tell me that it was false.

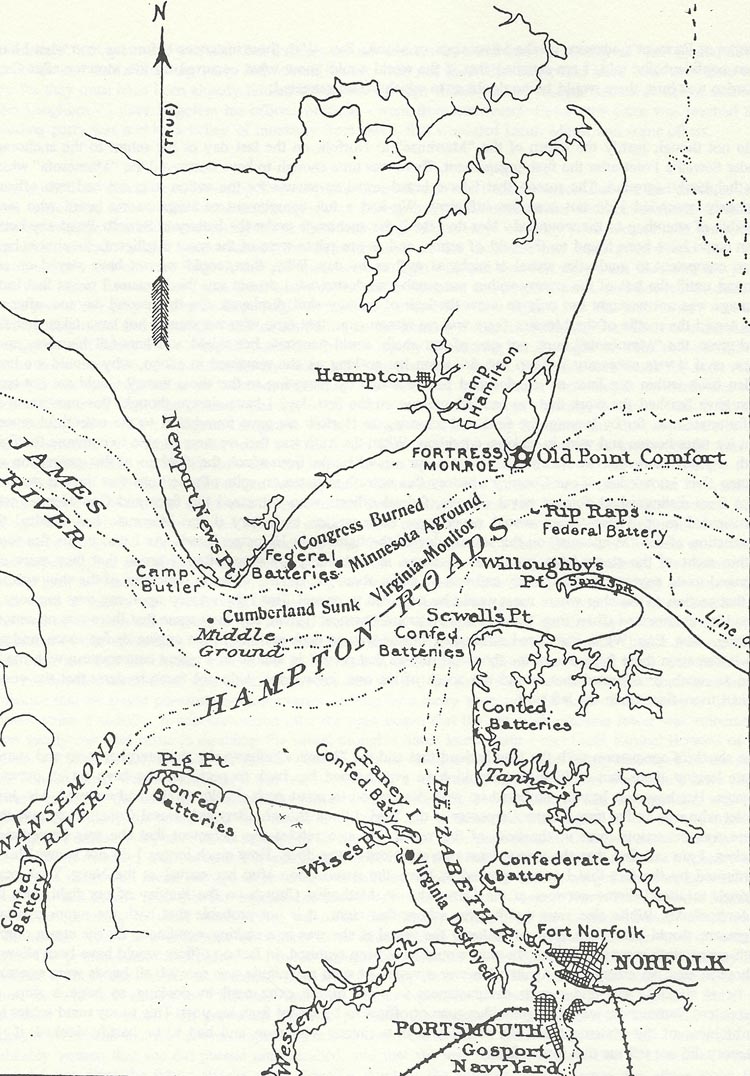

Map of Hampton Roads and Adjacent WatersWhile we were lying at the wharf the night of our arrival at the Yard, I think, I am told by Mr. Tynan that one of the firemen carelessly left a valve open which let water into the ship a great deal indeed. This incident had escaped my memory if I had ever heard of it, which it is probable I did not, for such mishaps are not published even among the officers of a ship. I sometimes think that some outsiders may have gotten hold of this and started the report that our ship leaked badly. This is only suspicions grounded upon what I learned from Mr. Tynan.

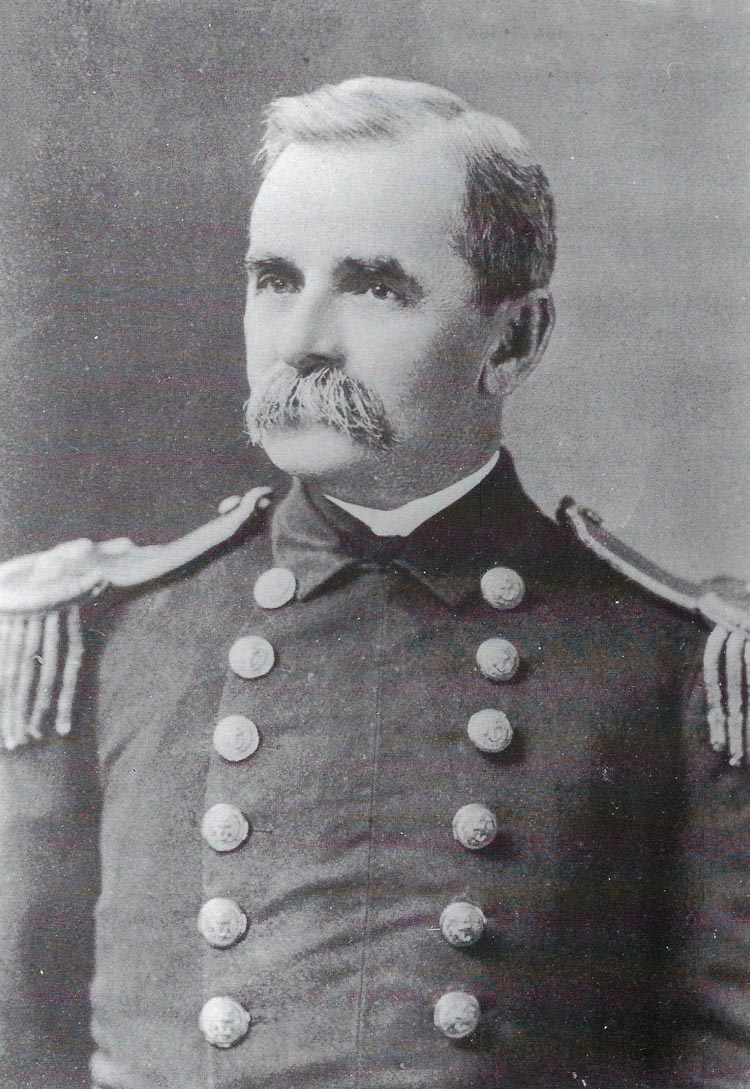

We went into drydock, strengthened the shield at its junction with the hull with knuckle irons, that is pieces of iron bent into a V shape, got solid projectiles for our rifled guns and were ready for another tilt with the enemy. Captain Joshua Tattnal relieved Lieut. Jones upon whom the command had devolved after Buchanan was wounded. The old hero was very feeble but as brave as any yet. Soon after our change of commanders [we heard firing down the river and learned that the enemy were bombarding Sewells Point. We got under way immediately; steam was ready]. *

* [. . . ] ruled out in the narrative.

He took us down the Roads again, steamed out under the guns of Rip Raps and fired a challenge gun to the "Monitor" which was lying plainly in sight. Why this invitation to another fight was not accepted or why the other vessels of our squadron were allowed to cut out two vessels loaded with supplies for the enemy I have never seen explained and would like to know. Whatever the reason may be, the fact remains that the "Monitor" neither responded to our challenge nor protected the government property from an enemy. This does not appear to agree with the report that we had been badly whipped and only escaped destruction through the fortunate recall of the "Monitor" as a Mr. Gee writes of the first fight. We were all anxious to try the metal of the "Monitor" again, as well as to put into execution a plan that had been developed to capture her by boarding. This was to approach her upon all sides with small boats and get possession of her deck. Then by getting on the unpierced side of her turret, a few men provided with long and thin pointed steel wedges were to drive them between it and the deck and thus jam it. Others were provided with balls of wicking or other fibrous material saturated with turpentine; these were to be fired and cast upon the top of the turret so that the burning fragments might fall upon the gunners within and drive them from their posts and set the ship on fire. Details for this daring expedition were eagerly sought by the officers, and plenty of men were found who would be wedge men or assigned to the firing party. But our foe could not be enticed out from her refuge in shoal water. So we returned to the Navy Yard.

The sounds of guns down the river and the report that the enemy was attacking Sewells Point caused a prompt departure for the threatened point. When we sighted the enemy and saw them pouring shot into our defences all expected some hot work. The "Monitor" was there, the "Galena" and several others. Before we were called to quarters, I heard Captain Tatnal say to the chief Pilot, "Mr. Parrish we will go through them giving them our broadsides right and left, and return and go at them like a bull in a narrow road." We were called to quarters but the enemy declined battle. We then anchored off our battery ashore and communicated with them, to learn the amount of damage that had been done them, and were glad as well as surprised that after so much firing no damage had been done at all.

After dark we observed large fires up the river and sent an officer with a boat's crew to investigate. He returned and reported that Norfolk was being evacuated. A council of the senior officers was called and I am told it was decided to lighten the vessel and attempt to pass up James River into our lines. We had gotten the wooden sides of our vessel several feet above water when this plan was abandoned and it was decided to destroy the ship.

At this time I was called from the hold where I was directing the men and at work, myself cutting rivets out of the water tanks to empty their contents into the bilge from which it was pumped overboard by our pumps, and placed at the signal bell. I took my station thinking that we would soon be in action. Judge then my surprise when I saw that we were steaming towards Norfolk. At first I thought that we had started as we were heading but would turn when we got headway enough to do so. But as we continued up without changing our course, I began to think that we were going up to protect the Navy Yard from the enemy.

All such hopes were soon rudely dispelled by Mr. Jones who came to me and said with a tremor in his voice, "Mr. Jack, you are assigned the command of a detail of firemen. Go muster your men and prepare them to abandon the ship. No baggage must be taken into the boats. You can leave your station; no more bells will be required." I turned away from my post to proceed to my new duties with a sad heart and tearful eyes at the approaching fate of this good ship that had to be so ignominiously deserted. I felt that I had rather go down in her like the brave crew of the "Cumberland" in honorable contest with the enemy. But older and wiser heads knew that it was necessary, I am told. Perhaps it was, but I felt like a coward skulking from the foe.

We soon reached the up harbor side of Craney Island where the ship was run aground, abandoned and set fire to. I landed early with my squad of firemen and formed them on the top of a low bank ashore ready for defence in case the enemy should come upon us by land. Other men were placed as outpost with instructions to fire upon anyone that advanced without answering the challenge. Our sailors made but sorry soldiers and were altogether out of their element ashore.

Just before all of the men had landed, a sentry on outpost fired. Our men were a little confused at first, and my squad nearly crushed me by jumping from the bank against which I was standing, watching for the burst of flame from the doomed ship. We soon quieted them however and formed behind the bank expecting a charge, but in a short time learned that it was a false alarm. The last boat did not reach shore before the flames began to rise from the port holes and hatches of the "Merrimac", and before we began our retreat towards Suffolk her guns began to discharge their charges, some towards us and other towards the Roads. We heard several of the shot whistle past.

We took up our mournful march for our line for we were now within the enemy's and expecting an attack at any moment. We had gotten but a few miles away when with an awful report the magazines of the burning ship exploded and hardly a vestige of her was left above the water. We reached Suffolk without any important adventures and then took the train for Richmond, Va.

Our crew were taken to Drewrie's Bluff, but in a day or two I was placed waiting orders, and stopped with Mr. Ege's family who were living then in the country on the North side of the James and not very far from Chapin's and Drewrie's Bluff.

I have seen in an article published twenty-five years after the destruction of the "Merrimac" that several skeletons were found in her wreck by divers that went down to recover the old metal from it. This is utterly false for the vessel was abandoned without any panic at all. The men were divided into squads and mustered by roll before leaving the ship and mustered again upon reaching the beach, so none could have been overlooked. When a crew is mustered, it is the duty of the Master-at-arms to account for every absentee and after him of the executive officers. If in spite of all this anyone should have been overlooked, the firing party in setting fire to the ship in many places as they did would have discovered them. The "brig" or place of confinement on a ship is usually the forward part of the bearth deck and whoever is in it is in plain view. This is sufficient to disprove this statement, but there is still a stronger proof that no skeletons were found. The ship was burned and did not blow up until the flames had burned through the thick deck above the magazines, and a person on the bearth deck would have been burned to a cinder before the explosion, and if not, it would have been shattered by it so that not a bone could be found in the hull.

Shortly after our officers and crew were quartered at the Bluff, the "Monitor" and "Galena" came up to attack it. I was not in the fight, but hearing the firing, Willie Ege and myself took shotguns and found the people who were going towards Chapins Bluff to do sharp shooting, but before we reached the bank of the river, the fleet had retreated, whipped again by the brave crew of the "Merrimac".

(This ends the narrative of the Monitor's engagements with the Merrimac

included in the undated notes that later becomes the Memoirs of E. A. Jack)Return to nnyindex2.htm and the

Battle of the Hampton Roads Ironclads