|

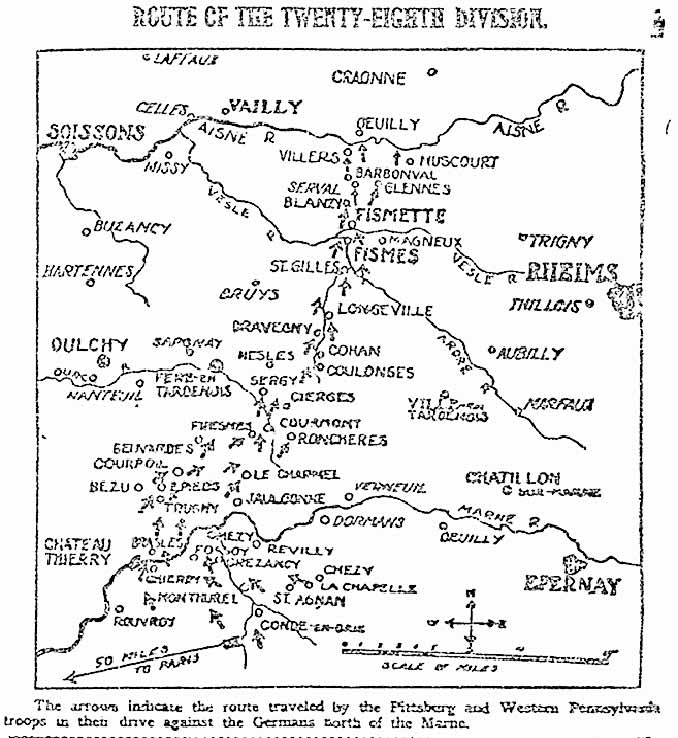

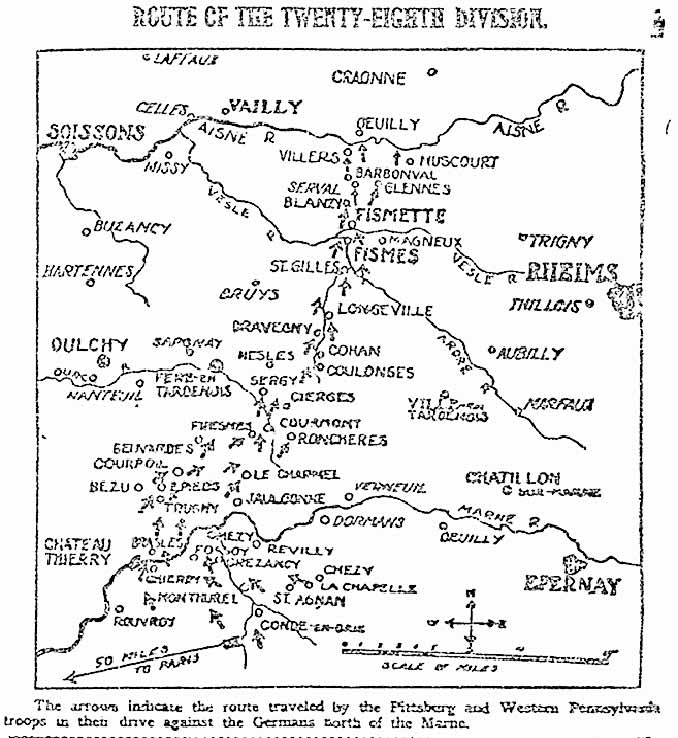

A History of Pittsburg and Western Pennsylvania Troops in the War

By John V. Hanlon (Copyright 1919 by The Pittsburg Press)

Chapter XII

(The Pittsburg Press, Sunday, March 23, 1919, pages 102-103)

Names in this chapter: Pollock, Williams, Thompson, Clarke, Brooks,

Wainwright, Cain, Ham, Brown, Helsel, Whitaker, Pennypacker, Muckel, Nunner,

Muir, Pershing

THE ENEMY FINALLY WITHDREW FROM FISMETTE AND ALONG THE

VESLE AND SOUGHT TO MAKE ANOTHER STAND AT THE AISNE. THE PITTSBURG AND WESTERN

PENNSYLVANIA TROOPS FOLLOWED CLOSE ON THE BOCHE’S HEELS AND HARRASSED HIM IN

EVERY POSSIB LE MANNER. THE ARTILLERY, TOO, KEPT POUNDING AWAY AND MANY OF THE

TOWNS WERE REDUCED TO PILES OF DUST. AT THE AISNE THE TWENTY-EIGHTH DIVISION WAS

WITHDRAWN AND SENT TOWARDS THE ARGONNE TO PARTICIPATE IN THE GREAT OFFENSIVE ON

THAT FRONT.

Capt. Robert Pollock

Considering the hellish fury of the fighting which

ensued in Fismes and Fismette, one cannot wonder or be astonished at statements

made by Capt. Robert Pollock of Pittsburg’s own “old Eighteenth”, upon his

return to Pittsburg from France. While still a convalescent at the Parkview

hospital, Capt. Pollock one evening addressed an audience of men in the Grace

Reformed church, Bayard and Dilbridge sts.

Capt. John M. Clark

“If I am shipped to hell,” said Capt Pollock, “I think

I can stand what the devil has for me, after going through what the Germans had

for us in Fismette. They used everything they had on us, from liquid fire down,

and many of my best friends were killed or wounded there.” Capt. Pollock himself

was wounded soon after Fismette was cleaned out and the Americans started for

the Ourcq river in pursuit of the stubbornly resisting Germans.

Here is the story of Fismette, as told by Capt.

Pollock:

It was in this scrap that Capt. Arch Williams was

wounded and Capt. John Clarke of Wilkinsburg, and Capt. Orville R. Thompson of

Pittsburg, killed. We were advancing on Fismette when they fell.

When we got into Fismette the real fighting started.

German Machine gunners occupied every window in every house in town. We had to

clear those houses before we could clean out the town, and our men were dropping

like flies. We had virtually no protection from that awful rain of fire from the

machine guns. The doughboys, though, went forward, and they mopped up. They went

into the first house in one block and you didn’t seem them again till they came

out of the last house on the block. They dug through walls from one house to

another, and every time they left a house the kaiser’s army was minus several

more men.

NO QUARTER ASKED OR GIVEN.

They asked no mercy and they showed none. They dug

through those walls, often with their bare hands, and they tore at those machine

guns like tigers. No wonder the German defense cracked, no wonder it fled before

those American doughboys. Many of our men went down, too, but they got a couple

for every one that went down. There wasn’t a live German left in town when they

got through.

One incident which occurred there is mighty strange. We

found only one inhabitant, aside from German soldiers, in the town. This was a

woman, a woman aged about 50. She said she had stayed in town to protect her

property. She started to tell some awful tales, but we hadn’t time to listed and

send her back to regimental headquarters. Subsequently the property which she

had been watching was destroyed, we destroyed it. That was when the Germans

recaptured the town and we had to shell them out.

OFFICERS ARE WOUNDED

After we drove them out again, however, we went

forward, moving toward our third objective: we had gained our first and second.

The third was the plateau between Vesle and the Aisne, northeast of Fismette. We

were well up on this place when I was hit. Lieut. Daniel W. Brooks of Swissvale

was killed at the same time. He was one of those fine fellows every person

likes. When I fell I didn’t be long. They came along, picked me up and started

me for the hospital and the last I saw of my men when, led by Lieut. Edward Z.

Wainwright, they were moving over the brow of the hill on to their objective.

Among the many strange things about the battles that

the old Eighteenth participated in was that it once faced the Eighteenth

regiment of the German army. This sounded so “fishy” the captain said, that

Capt. Robert Cain of Pittsburg, cut the shoulder straps from a captain of the

regiment, who had been killed and send them to his wife.

Reverting to the thread of our present narrative, the

German guns from their hilltops still poured in a galling fire on the American

positions. Still their snipers and machine gunners hung on in Fismette. To have

attempted to cross the Vesle river under such bombardment would have been

hazardous in the extreme. An attack in force was obviously impossible and it was

at this point in the campaign that the American and allied commanders faced some

of their most serious and perplexing problems. The Yanks were chafing for more

and more action, although their efforts to this point had bordered on the

superhuman. They were like raging tigers when they remembered how many of their

brave comrades had fallen victims of foe bullets and other means of human

destruction.

All the streets of Fismette were filled with fighters.

The combat continued with unabated fierceness and varying fortunes for either

side until Aug. 28, when the Germans came down out of their hills in a raging

tide of savage and brutal destroyers. Bouting into Fismette, they drove the

little force of Americans back to the river, where an amazingly few men managed

to held a bridgehead on the northern bank.

RESISTANCE IN VAIN

This desperate resistance, however, proved in vain, for

the time being, and the town again fell into the hands of the German hordes.

The American gunners then began systematically to level

the town, for the Yankee commanders had been forced to abandon all hopes of

taking it by infantry assault without an unjustifiable loss of brave,

wonderfully brave, men.

Elsewhere along the great battle line great events of

vast importance in a military sense had been taking place while these

developments at Fismette were in progress. In Flanders the British troops,

supported by American brigades fighting shoulder to shoulder with them, had been

driving the Germans eastward, while further south the French were keeping the

Hun on the run and demonstrating to the Berlin warlords in no uncertain fashion

that the boastful and ruthless warriors from the “Fatherland” were by no means

invincible. American forces around Soissons were pounding away at the Germans in

such fashion as to make the Teuton positions as long the Vesle river untenable.

Even the stubborn defenders of these positions soon began to realize that they

could not hold on there much longer without tremendous losses of man power and

guns and ammunition.

Among the brace Americans at Fismette, just at this

time, little was known of the developments in the other sections. They fought on

with bulldog courage, however. Even the junior officers of the Americans were

greatly surprised when word came back Sept. 4 that the patrols north of the

river had met almost no opposition from the enemy in their latest forward

movements toward the Rhine, which still seemed very far away indeed. Next it was

noticed that the foe’s artillery fire had fallen off to a little desultory

shilling, so a general advance was ordered. Roads in the rear at once became

alive with big motor trucks, big guns, wagon trains, columns of men and all the

countless activities of an army on the march. It was a wonderful sight to see

that main force crossing the river. Officers standing on the hills overlooking

the scene declared later that it was one they never could forget. The long

columns debouched from the wooded shelters, deployed into wide, thin lines and

moved off down the slope into the narrow river valley.

TOWNS POUNDED TO DUST

The village and towns of the Vesle valley, pounded

almost to dust by the thousands of shells which had fallen on them during the

two weeks the armies contended for their possession, lay before the advancing

Americans. Down the hill those brave Yanks went, moving just as they had done

times without number in training camps in sham battles and war maneuvers.

Occasionally there was a burst of black smoke and a spouting geyser of earth and

stones to show that this was, after all, real warfare and that the lives of the

advancing men were constantly “on the knees of the gods.”

Even these incidents had been so well simulated in the

mimic warfare of the training days that they seemed to make little impression to

the observers, held spellbound as they were by the dramatic values of the

momentous and history-making drama being unrolled before their eyes. The

greatest ocular evidence that his indeed was real warfare came when now and then

a man or two dropped and either lay still or got up and limped slowly back up

the hill. Many of the officers who watched the whole performance compared to

scenes they had witnessed sometimes safely in motion picture theaters.

Occasional casualties served not at all to slacken or

impede the advance of the defenders of right, truth, democracy and justice. When

the live, moving steadily forward, reached the river, there was little effort to

converge at the hastily constructed bridges but the men who were close enough

walked over them, while the others plunged into the water and either waded or

swan across, according to the depth where they happened to be and the

individual’s ability to swim.

On toward the Aisne river the column moved after

reaching the northern side of the Vesle. Up the long slope the men went as

p\imperturbably as they had come down the other side, although every man of them

knew that when they reached the crest of the rise they would face the deadly

German machine gun fire from the positions on the next ridge to the north.

Never faltering even for an instant, the thin line of

the Yanks went over the crest of the rise and disappeared from the view of the

watchers behind. The German machine gunners resisted desperately retiring only

foot by foot. The Americans, seemingly glad that the fight was on once more,

refused to be checked in their great advance. Prediction had been freely made

that the Germans would make their next stand on a high plateau between the Vesle

and the Aisne. The pressure elsewhere on his libe [sic] made this impossible and

the Huns plunged on northward, while ever after him came the inevitable,

inscrutable, inescapable American doughboy.

COL. HAM WOUNDED

One of the American units which met real opposition at

about this stage of the advance was the One Hundred and Ninth infantry, which

crossed the river from Magneux some distance to the west of Fismette. Col.

Samuel V. Ham, regular army officer commanding the regiment, led the firing line

across the river and in its advance toward Muscourt. During a hot engagement, he

was wounded so severely that he was unable to move, but he declined to be

evacuated. For 10 hours after that he remained on the field, directing the

attack and refusing to leave or receive medical or surgical attention until his

men had seen every care and comfort which could be afforded them under the grim

circumstances of such a battlefield.

For his great showing of bravery and heroic conduct,

Col. Ham was awarded the distinguished service cross. The citation which

accompanied the awarding of the coveted cross declared that “Col. Ham

exemplified the greatest heroism and truest leadership, instilling in his men

confidence in the undertaking.” He was the third commander the regiment had

since going to France. Col. Brown had been transferred and Col. Coulter had been

wounded. All except these first two were regular army men and the regiment had

eight commanders in two months.

Fifteen miles away the towers of the cathedral at Laon

could be seen by the Americans. From the high ground ahead, to which the Yank

heroes advanced with all possible speed, the lowlands to the north spread out

before them. Laon had been since 1914 the pivot of the German line. It was the

bastion on which the tremendous front of the Hun armies turned from north and

south to east and west. The lowlands represented defiled and invaded France in a

very real sense and the sight of the cathedral towers, seen dimly in the misty

distance, thrilled the tired fighters from across the Atlantic, even when much

of their strength and their irrepressible enthusiasm had been spent in the

terrible fighting of the past few days and weeks.

The One Hundred and Ninth infantry covered itself with

glory in the advance across the five miles of hill, valley and plateau between

the Vesle and the Aisne. Co. C of the One Hundred and Ninth suffered heavy

losses and on the Aisne plateau this company displayed amazing morale and the

fighting ability and strength with tenacity of purpose so characteristic of all

the American fighters in the world war for freedom.

After the capture of a small wood below the village of

Villers-en-Prayeres, which was described in an official communiqué as “a small

but brilliant operation,” Co. G of the One Hundred and Ninth infantry ranked

with Co. B and Co. C for their gallant stand and heavy losses south of the

Marne. There were 125 casualties in the company of 260 men.

YANKS SUFFERED HEAVILY

At times during these extremely hazardous operations,

following so soon after the taking of Fismes and Fismette from the Germans, the

Americans were subjected to a heavy artillery fire, especially while crossing

the plateau. During the advance over about the first two miles it was necessary

for the doughboys to go forward in the open across high ground, plainly visible

to the German gunners and constantly swept by their deadly and destructive fire.

There was little cover and, thought it was very difficult later of obtain

accurate reports of the losses, the Yanks [unreadable] are known to have

suffered heavily through this part of their advance toward the homeland of the

Hun.

Private Paul Helsel came out of that period of the

fighting with six bullet holes through his shirt. Two bullets had gone through

his trousers, the bayonet of his rifle had been shot away and a bullet was

embedded in the first-aid pack he carried [unreadable]. It was considered

miraculous not only be himself but by his comrades and his superior officers,

that he escaped without a wound of any kind.

Light and heavy artillery swept the plateau across

which the Americans were advancing. Their losses would undoubtedly have been

much heavier had they advanced in the regular formations. Instead of doing so,

they were filtered into and through the zone, never presenting a satisfactory

artillery target for the foe gunners. On their stand on the Vesle, the Germans

had been enabled to save the bulk of the supply they had accumulated there.

Whatever they were unable to remove they burned, so it would not be of any

material assistance to the advancing Americans. Great fires sent up dense clouds

of smoke, marking in the distance the sports where large ammunition dumps and

other stocks of supplies were being destroyed.

During their progress forward from the Vesle the

American soldiers had presented before their watchful eyes a different vista

from that which they had seen between the Marne and the Vesle, where the way had

been impeded to a great extent in some places by the almost unimaginable

quantities of supplies of every conceivable kind which the Hun had abandoned

when forced to hasty flight, for which he could not possibly have prepared

adequately on such short notice as was allowed by the ever alert fighters for

democracy and freedom. Sept. [unreadable] the pursuit had come to an end and the

Americans and French were on the Aisne river. The enemy again was bristling in

his de[unreadable] across a water barrier.

BLAST HUNS FROM AISNE

The infantry regiments were followed by artillery as

far as the high ground between the rivers. There the artillery took positions

from which they started to blast the Huns away from their hold on the Aisne and

start them backward to their next line of defense, the vicinity of the ancient

and historic Chemo-des-Dames, or Road of Women.

Battery C, One Hundred and Seventh regiment, of

Phoenixville, commanded by Capt. Samuel A. Whitaker of that town, a nephew of

Samuel W. Pennypacker, one-time governor of Pennsylvania, was the first of the

Pennsylvanians big gun units to cross the Vesle at that point.

The night of Sept. 7, the One Hundred and Seventy was

relieved by the Two Hundred and Twenty-first French Artillery regiment, near

Blanzy-des Fismes [sic]. The French used the Americans’ horses. They discovered

they had taken a wrong road in moving up and, just as they turned back, the

Germans who had learned of the hour of the relief, laid down a heavy barrage.

Lieut. John Muckel, of Battery C with a detail of men,

had remained with the French regiment to show them the battery position and

bring back the horses. When the barrage fell, he was thrown 25 feet by the

explosion of a high-explosive shell, and landed plump in the mangled bodies of

two horses. All about him were the moans and cries of the wounded and dying

Frenchmen. He had been so shocked by the shell explosion close to him that he

could only move with difficulty and extreme pain. He was barely conscious, alone

in the dark and lost, for the regiments had gone on and his detachment of

Americans scattered.

SHELLS FOLLOW OFFICER

Lieut. Muckel, realizing he must do something dragged

himself until he came to the outskirts of a village, which he learned later was

Villet. Half dazed he crawled to the wall of a building and pulled himself to

his feet. He was leaning against the wall, trying to collect his scattered

senses, when a shell struck the building and demobilized it.

The lieutenant was half buried in the debris. As he lay

there, fully expecting never again to rejoin his battery, Sergt. Nunner, of the

battery, came along on horseback and heard the officer call. The sergeant wanted

the lieutenant to take his horse and get away. The lieutenant refused, and

ordered the sergeant to go on and save himself. The “noncom” then committed the

militarily unpardonable sin or insubordination, by refusing to obey, and

announcing that he would stay with the office if the latter would not get away

on the horse. At last they affected a compromise whereby the sergeant rode the

horse and the lieutenant helped himself along by holding to the horse’s tail.

Thus they caught up with the battery.

The Twenty-eighth division was relieved at the Aisne

Sept. 8, 9 and ordered back to a rest camp, after about 60 days of unremitting

day and night fighting by the infantry and approximately a month of stirring

action by the artillery.

NAMED “IRON DIVISION”

The men were exhausted but were borne up and sustained

by the knowledge that they had accomplished almost impossible tasks and had

vanquished the most famed regiments of the kaiser’s soldiery. It was after the

completion of this work and their withdrawal from the Aisne that the

Twenty-eighth commenced to be spoken of as the “Iron Division.” Just who was

responsible for this designation has not been definitely established although

the remark: “You are not soldiers! You are men of iron,” has been attributed to

Gen. Pershing.

Anyhow the higher officers soon heard of it and it

rapidly filtered down through the ranks and likewise through the entire American

Expeditionary Force with the result that thereafter our old Pennsylvania guard

unit was always spoken of as the “Iron Division.” And that it was a well earned

title all will agree for it is written upon the [unreadable] of France in

letters of blood and it is blasted so deep into the memory of the Huns that

countless ages will not cause it to fade.

From the time of entering the conflict a the Marne when

the enemy was turned back from the gates of Paris and started on that long

retreat northward from which he was never able to recover until the Vesle river

was reached our Pittsburg and Western Pennsylvania soldiers as well as all those

of the Keystone state suffered terrible. The toll of death and injury was heavy

and in some of the regiments as many as 1,200 replacements were necessary to

bring them up to the required battle strength.

They were praised in general orders by both our own and

allied high commands and they had long since been recognized as “shock troops”

the highest known type of soldiers. Citations brought to the division the

designation of “Red” and the men were accorded the honor of wearing upon their

coats the scarlet keystone. And when you see a scarlet keystone you know that

the wearer has proven upon the field of battle that he is the peer or any

fighting man in the world.

After their days of strenuous work our boys were

thinking of a well-earned rest from the rigors of the firing line for a few

weeks at least but they were disappointed. The emergency which had caused Gen.

Pershing to brigade the Americans with the French and British has [unreadable]

and the first American army was in the forming when the Pennsylvanians turned

back from the Vesle. While the Twenty-eighth had been battling against the Hun

transports and had been rushing many thousands of Americans to France where they

were given preliminary training and it was now proposed to have an entire army

entirely American and responsible to only Gen. Pershing and the supreme

commander Marshal Foch.

PRAISED BY COMMANDER

While the men were grumbling over the change in plans

whereby they were ordered into another sector to become part of this new army

they were cheered somewhat by the fact that their labors had not been unnoticed

by those in high places. In a general order from division headquarters read to

all the regiments the commanding officer Gen. Muir set forth:

“The division commander is authorized to inform all,

from the lowest to the highest, that their efforts are known and appreciated. A

new division by force of circumstances, took its place in the front line in one

of the greatest battles in the greatest war in history.

“The division has acquitted itself in a creditable

manner. It has stormed and taken points that were regarded as proof against

assault. It has taken numerous prisoners from a vaunted guards division of the

enemy.

“It has inflicted on the enemy far more loss than it

has suffered from him. In a single gas application it inflicted more damage than

the enemy inflicted on us by gas since its entry into battle.

“ It is desired that these facts be brought to the

attention of all, in order that the tendency of new troops to allow their minds

to dwell on their own losses to the exclusion of what they have done to the

enemy, may be reduced to the minimum.

“Let’s all be of good heart! We have inflicted more

loss than we have suffered, we are better men individually than our enemies. A

little more grit, a little more effort, a little more determination to keep our

enemies down, and the division will have the right to look on itself as an

organization of veterans.”

So away they went to the southeast and came to a halt

in the vicinity of Reviguy, just south of the Argonne Forest and about a mile

and a half north of the Rhine-Marne canal. Here they found detachments awaiting

them, and once more the sadly depleted ranks were filled.

The division was under orders to put in 10 days at hard

drilling there. This is the military idea of rest for soldiers, and experience

has proved it a pretty good system, although it never will meet the approval of

the man in the ranks. It has the advantage of keeping his mind occupied and

maintaining his discipline and morale.

The best troops will go stale through neglect of drill

in a campaign – and drill and discipline are almost synonymous. As undisciplined

troops are worse than useless in battle, the necessity of occasional periods of

drill, distasteful through they may be to the soldier, is obvious.

“A day in a rest camp is about as bad as a day in

battle,” is not an uncommon expression from the men, although, as is always the

case with soldiers, they appreciate a change of any kind.

Thus rest camp and its drills were not destined to

become monotonous, however, for instead of 10 days they had only one day. Orders

came from “G.H.Q.” which is soldier parlance for general headquarters, for the

division to proceed almost directly north into the Argonne. This meant more hard

hiking and more rough traveling for horses and motor trucks until the units

again were “bedded down” temporarily, with division headquarters at Les Islettes,

20 miles due north from Reviguy, and eight miles south of what was then, and had

been for many months, the front line.

FACING MORE HARD WORK

The doughboys knew that something big was impending.

They had come to believe that “Pershing wouldn’t have the Twenty-eighth division

around unless he were going to pull off something big.” They felt more at home

than they had since leaving America.

All about them they saw nothing by American soldiers,

and thousands on thousands of them. The country seemed teeming with them. Every

branch of the service was in American hands, the first time the Pennsylvanians

had seen such an organization of their very own – the first time anybody ever

did, in fact.

Infantry, artillery, engineers, the supply services,

tanks, the air service, medical service, the high command and the staff, all

were American. It was a proud day for the doughboys when showers of leaflets

dropped from a squadron of airplanes flying over one day and they read on the

printed pages a pledge from American airmen to co-operated with the American

fighting men on the ground to the limit of their ability and asked similar

co-operation from the foot soldiers.

FLYERS PLEDGE SUPPORT

“Your signals enables us to take the news of your

location to the rear,” read the communication, “to report if the attack is

successful to call for help if needed, to enable the artillery to put their

shells over your head into the enemy. If you are out of ammunition and tell us,

we will report and have it sent up. If you are surrounded we will deliver the

ammunition by airplane.

“We do not hike through the mud with you, but there are

discomforts in our work as bad as mud, but we won’t let rain storms, Archies

(anti-aircraft guns) nor boche planes prevent our getting there with the goods.

Use us to the limit. After reading this, hand it to your buddies and remember to

show your signals.” It was signed: “Your Aviators.”

“You bet we will, all of that,” was the heartfelt

comment of the soldiers. Such was the splendid spirit of co-operation built up

by Gen. Pershing among the branches of the service.

To this great American army was assigned the tremendous

task of striking at the enemy’s vitals, striking where it was know he would

defend himself most passionately. The Germans defensive lines converged toward a

point in the east like the ribs of a fan, drawing close to protect the

Mezieres-Longuyon railroad shuttle, which was the vital artery of Germany in

occupied territory.

If the Americans could force a break through in the

Argonne, the whole [unreadable] German machine in France would collapse. Whether

they broke through or not, the smallest possible result of an advance there

would be the narrowing of a bottle neck of the German transport lines into

Germany and a slow strangling of the invading forces.

Of this first phase of the Argonne-Meuse offensive Gen.

Pershing in his report to the secretary or war said: “On the day after we had

taken the St. Mihiel salient, much of our corps and army artillery which had

operated at St. Mihiel, and our divisions in reserve at other points, were

already on the move toward the area back of the lines between the Meuse river

and the western edge of the Forest of Argonne. With the exception of St. Mihiel,

the old German front line from Switzerland to the east of Rheims was still

intact. In the general attack planned all along the line, the operation assigned

the American army as the hinge of this allied offensive was directed toward the

important railroad communications of the German armies through Mesicres and

Sedan. The enemy must hold fast to this part of his lines or the withdrawal of

his forces with four years’ accumulation of plants and material would be

dangerously imperiled.

“The German army had as yet shown no demoralization,

and, while the mass of its troops had suffered in morale, it first class

divisions and notably its machine gun defense were exhibiting remarkable

tactical efficiency as well as courage. The German general staff was fully aware

of the consequences of a success on the Meuse-Argonne line. Certain that he

would do everything in his power to oppose us, the action was planned with as

much secrecy as possible, and was undertaken with the determination to use all

our divisions in forcing a decision. We expected to draw the best German

divisions to our front and consume them, while the enemy was held under grave

apprehension lest our attack should break his line, which it was our firm

purpose to do.

“Our right flank was protected by the Meuse, while or

left embraced the Argonne Forest, where ravines, hills and elaborate defenses

screened by dense thickets had been generally considered impregnable. Our order

of battle from right to left was the Third corps, from the Meuse to Malancourt,

with the Thirty-third, Eightieth and Fourth divisions in line and the Third

division as corps reserve, the Fifth corps from Malacourt [sic] to Vauquois,

with the Seventieth, Thirty-seventh and Ninety-first divisions in line and the

Thirty-second division corps reserve and the First corps from Vauquois to

Quienne-le-Chateau, with the Thirty-fifth, Twenty-eighth and Seventy-seventh

divisions and the Ninety-second in corps reserve. The army reserve consisted of

the First, Twenty-ninth and Eighty-second division.

“On Sept. 25 our troops quietly took the place of the

French and thinly held the line in this sector, which had long been inactive.”

|