REPORT OF THE COMMISSION TO LOCATE THE SITE OF THE FRONTIER FORTS OF PENNSYLVANIA.

VOLUME TWO.

CLARENCE M. BUSCH.

STATE PRINTER OF PENNSYLVANIA.

1896.

THE FRONTIER FORTS OF WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA.

FORT LIGONIER.

Part I.

Pages 194-236.

Useful map for this chapter: Historical Map of Southwestern Pennsylvania.

Within three years after the defeat of Braddock, (1755), another army was organized under orders of the British government, with the assistance of the middle colonies, for an offensive campaign particularly directed against Fort Duquesne. Brigadier John Forbes was entrusted with the command. He waited at Philadelphia until his army was ready, and it was the end of June, (1758), before they were on the march. His forces consisted of provincials from Pennsylvania, Virginia, Maryland, and North Carolina, with 1200 Highlanders of Montgomery's regiment and a detachment of Royal Americans, amounting in all, with wagons and camp followers, to between six and seven thousand men.

The Royal American regiment was a new corps raised in the colonies, largely among the Germans of Pennsylvania. Its officers were from Europe; and of the most conspicuous among them was Lieut.-Col. Bouquet, a brave and accomplished Swiss, who commanded one of the four battalions of which the regiment was composed. (1.)The troops from Virginia, North Carolina and Maryland were ordered to assemble at Winchester, in Virginia, under Colonel Washington; and the Pennsylvania forces at Raystown, now Bedford. Bouquet preceded Forbes, who was attacked by a painful and dangerous malady which disabled him from leaving Philadelphia for some time, and from which he suffered direfully throughout the whole campaign.

Bouquet with the advance division was at Raystown early in July, (1758). Here in an opening of the forest, by a small stream, were his tents pitched; and Virginians in hunting shirts, Highlanders in kilt and plaid, and Royal Americans in regulation scarlet, labored at throwing up intrenchments and palisades.

And here, before the army set out on its way through the wilderness, from this the verge of civilization, a question rose as to the route to be pursued; whether the army should hew a road through the forest, or march 34 miles to Fort Cumberland, (Md.) and thence follow the road which had been made by Braddock. The Pennsylvanians urged the former; the Virginians, with Washington as their most active and zealous speaker, insisted on the latter route. It was finally determined, upon the opinion of Sir John Sinclair, quarter master-general, who had accompanied Braddock, and of Col. Armstrong, to whose opinion Forbes and Bouquet paid great deference, as well as from reasons which appeared to be convincing to Bouquet and himself, that the course should be direct through Pennsylvania, from which conclusion it was necessary that a new road should be made from that point (2), and by the 1st of August, (‘58), a large force was employed opening out and making the new road for the passage of the army between Bedford and the Laurel Hill. (3.)

Meanwhile Bouquet's men pushed on the heavy work of road-making up the main range of the Alleghenies, and, what proved far worse, the parallel mountain ridge of Laurel Hill, hewing, digging, blasting, laying fascines and gabions to support the track along the sides of steep declivities, or worming their way like moles through the jungle of swamp and forest. Forbes described the country to Pitt as an "immense uninhabited wilderness, overgrown everywhere with trees and brushwood, so that nowhere can one see twenty yards." In truth, as far as eye or mind could reach, a prodigious forest vegetation spread its impervious canopy over hill, valley and plain, and wrapped the stern and awful waste in the shadows of the tomb. (4.)

Forbes, still very ill, was obliged to rest on his way at every step of his progress, as the nature of his disease—being an inflammation of the stomach and bowels—was such as required rest of body. He was carried on a kind of litter, swung between two horses. It was a little before September when he reached Bedford, where he was joined by Washington.

The advance of Bouquet's force before this time had reached the Loyalhanna, and under Col. Burd of the Pennsylvania regiment, (5), had begun the erection of a stockade and fortified camp. (6.)

The plan adopted by those who were in command, and carried out by Forbes, was, instead of marching like Braddock, at one stretch for Fort Duquesne, burdened with a long and cumbrous baggage-train, to push on by slow stages, establishing fortified magazines as they went, and at last, when, within easy distance of the fort, to advance upon it with all his force, as little impeded as possible with wagons and pack-horses.

The western base of Laurel Hill along which flows the Loyalhanna had been fixed upon as the point at which there should be a general gathering of the army before any serious attempt was made to advance farther westward. The first camp of the soldiers who took up their position here was called the "Camp at Loyalhannon;" the place taking its name from the creek in its English form, which itself is a variation of its Indian name. The old Indian path direct from their village and trading point near the Forks of the Ohio to Raystown and the east, crossed the creek here. It was known as the Loyalhannon, or cognate name, long before the time when it was occupied by the English. (7.)

About the first of September, (‘58), nearly all of Bouquet's division consisting of about 2500 men, were encamped about the Loyalhanna. It is probable, moreover, that a more advanced position had even been taken at a point about ten miles west, on the old trading path, on the bank of the Nine-Mile run, a tributary of the Loyalhanna. Gen. Forbes, in a letter dated at Fort Loudoun, Sept. 9th, 1758, says that the road over the mountains, and the communication was then "effectually done to with[in] 40 miles of the French Fort." (8.)While the advance of the army lay at the Loyalhanna awaiting the arrival of the General, occurred the unfortunate affair of Major Grant's Defeat—the most disastrous episode of this campaign.

Major James Grant, of the Highlanders, had begged Bouquet to allow him to make a reconnoisance in force to the enemy's fort, and being allowed permission to do so, had received special orders not to approach too near the fort if there were any indications of resistance, and in no event to run the hazard of a combat, if it could be avoided.

He left the camp on the 9th of Sept. with a force of 37 officers and 805 privates. Without having been discovered by the enemy—which was a remarkable thing—he succeeded on the third day after, in reaching the hill which overlooked Fort Duquesne. He then, very imprudently, prepared his plans to draw the enemy out; flattering himself that he could readily defeat them. He based his expectations on an utter ignorance of the methods of his enemy, of the qualities of most of his own men, and of the strength of his opponents. The French within a day or two before had received reënforcements from the Illinois.

In the early morning of the 14th (Sept., ‘58), while the fog yet lay on the land and river, he sent a few Highlanders to burn a ware-house standing on the cleared ground. He did this to draw out the enemy, and had the bagpipes play and the reveille to be beaten to comfort his men * * * * * * The roll of the drums was answered by a burst of war-whoops, and the French came swarming out, many of them in their shirts, having just leaped from their beds. They came together and there was a hot fight in the forest, lasting about three-quarters of an hour. At length the horrors of such warfare, to which the Highlanders were not at all used, the frightful yells and hideous appearance of the barbarians, their overpowering number, their own ignorance of such a method of fighting completely overcame them. They broke away in wild and disorderly retreat. * * * * The only hope was in those Virginians whom Grant had posted back so that they might not share the honor of victory. Lewis had pushed forward, on the sound of the battle, but in the woods he missed the retreating Highlanders. Bullitt and his Virginia company stood their ground, and they kept back the whole body of French and Indians till two-thirds of his men were killed. They would not accept quarter. The survivors were driven into the Allegheny, where some were drowned, others swam over and escaped. * * * * * Grant was surrounded and captured, (9), and Lewis, who presently came up, was also made prisoner, along with some of his men. * * * * The English lost 273 killed, wounded and taken. The rest got back safe to the camp at Loyalhanna.

The French did not pursue their immediate advantage with the zeal which their success would have justified. From all accounts they made special efforts to make prisoners rather than kill, and the loss of dead was suffered mostly at the hands of the Indians. The French who had full knowledge of the movements of the army, and who knew that only a part of it had arrived at the Loyalhanna, determined, notwithstanding the defection of their allies, after their victory over Grant, to make an attack on the camp without the loss of time and before the entire army should come up. The Indians now showed every sign of disaffection. They were getting tired of the French, and were anxious to get home to their squaws and papooses. But above all, the wonderful influence of that remarkable man, Frederick Post, in whom the savages had implicit confidence, and who was among them at this time as the agent of the Province, was successful in alienating them from their old confederates.

Accordingly, the united forces of the French and Indians, by a premeditated arrangement sallied forth and with great desperation attacked the English in their camps around the stockade, and even the stockade itself. After a bitter engagement they were repulsed; and from this repulse they never succeeded in gathering their forces together again in sufficient numbers to encourage them to risk the chances of another engagement. In the woods around Fort Ligonier, the French and their barbarian allies met in battle for the last time the English, in their contest for the region of the Ohio.

But in the interim, and up to the time when they were chased back from the Loyalhanna, the enemy harassed the English in every way conceivable, but especially by lying in wait and ambushing detachments separated from the others, and by constantly destroying the horses and cattle. This warfare was carried on all round this post, both eastward and westward of the camp and all through the woods surrounding it.

Very meagre accounts of this engagement which came off here at Ligonier on this occasion when the French and Indians attacked the English, are available. In its results, however, it was of great moment and consequence. In the history of the conflict with the barbarians, single engagements must, nearly always, be considered in connection with or in relation to events of which they are merely a part. What the result would have been had the English at Loyalhanna fallen to the mercy of their enemies, can only be conjectured. It is certain that the battle was one of magnitude and desperation. There is quite enough testimony from the best sources to fix this beyond doubt; and its effect on the subsequent part of the campaign and on the history of the time was no less a matter for congratulation for the English than of mortification and ill omen to the French. The more we know of the actual condition of affairs at that time, the more apparent it becomes that this engagement was of the greatest moment in its results.

The following extracts from the Pennsylvania Gazette, October 26, 1758, &c, give some particulars of the action of the 12th:

"Extract of a letter from Loyal Hanning, dated 14th:"We were attacked by 1200 French and 200 Indians, commanded by M. de Vetri, on Thursday, 12th current, at 11 o clock, A. M., with great fury until 3 P. M, when I had the pleasure of seeing victory attend the British arms. The enemy attempted in the night to attack us a second time; but in return for their most melodious music, we gave them a lesson of shells, which soon made them retreat. Our loss on this occasion is only 62 men and 5 officers, killed, wounded, and missing. The French were employed all night in carrying off their dead and wounded, and I believe carried off some of our dead in mistake."

"Extract of a letter from Raystown, October 16, 1758:

"Yesterday the troops fired on account of our success over the enemy, who attacked our advanced post at Loyal Hanning the 12th inst.; their number, by the information of a prisoner taken, said to be about 1100. The engagement began about 11. o clock A. M., and lasted till 2. They renewed the attack thrice, but our troops stood their ground and behaved with the greatest bravery and firmness at their different posts, repulsing the enemy each time, notwithstanding which, they did not quit the investment that night, but continued firing random shots during that time. This has put our troops in good spirits. The accounts are hitherto imperfect, which obliged the General to send a distinct officer yesterday to Loyal Hanning to learn a true account of the affair. By the General's information, they only took one wounded soldier, and say nothing of the killed, though it was imagined to be very considerable, if they attacked in the open manner it is reported they did. Colonel Bouquet was at Stony Creek, with 700 men and a detachment of artillery. He could get no further on account of the roads, which, indeed, has impeded everything greatly. Tonight or to-morrow a sufficient number of wagons will be up with provisions. Killed 12, wounded 18, missing 31. Of the missing 29 were on grass guards when the enemy attacked." (10.)

It will be seen from the list of those killed, as also from the reports, that at this day the most of the army at Loyalhanna was composed of provincials. Bouquet himself was not at the camp at the time of the engagement. Col. James Burd was in command, and the following is his account in a letter written the same day. (11.)

"Camp at Loyal Hannon, Oct. 12, 1758.

"To Col. Bouquet at Stoney Creek on the Laurel Hill:I had the pleasure to receive your favors of this date this evening at 7 P. M. I shall be glad to see you. I send you, through Lieut. Col. Lloyd (who marches to you with 200 men), the 100 falling axes, etc., you desire.

‘This day, at 11 A. M., the enemy fired 12 guns to the southwest of us, upon which I sent two partys to surround them; but instantly the firing increased, upon which I sent out a larger party of 500 men. They were forced to the camp, and immediately a regular attack ensued, which lasted a long time; I think about two hours. But we had the pleasure to do that honour to his Majesty's arms, to keep his camp at Loyal Hannon. I can't inform you of our loss, nor that of the enemy. But must refer to for the particulars to Lieut. Col. Lloyd. One of their soldiers, which we have mortally wounded, says they were 1200 strong and 200 Indians, but I can ascertain nothing of this further, I have drove them off the field; but I don't doubt of a second attack. If they do I am ready." In a postscript he adds: "Since writing we have been fired upon." (12.)

In a letter of Henry Bouquet's dated at "Ray's Dudgeon, Oct. 13, 1758, 10 P. M." (13.) He says:

"After having written to you this morning, I went to reconnoitre Laurel Hill, with a party of 80 men, some firing of guns around us made me suspect that it was the signal of an enemy's party. I sent to find out, and one of our party having perceived the Indians, fired on them. We continued our march and have found a very good road for ascending the mountain, although very stony in two places. The old road is absolutely impracticable.

"I have had this afternoon a second letter from Colonel Burd. The enemies have been all night around the entrenchments, and have made several false attacks. The cannon and the cohortes (14) have held them in awe, and until the Colonel had sent to reconnoitre the environs, he was not sure that they had retired. At this moment is heard from the mountains several cannon shots which makes me judge that the enemies have not yet abandoned the party, and at all events I am going to attempt to reenter this post before day. The 200 men which Colonel Burd sent to me, have eaten nothing for two days. I received this moment provisions from Stoney Creek and will depart in two hours.

"I have not any report of our loss, two officers from Maryland have been killed, and one wounded. Duncannon of Virginia mortally wounded, also one officer in the first battalion of Pennsylvania, and nearly fifty men.

"The loss of the enemy must be considerable to judge by the reports of our men and the fire which they have already wasted. Without this cursed rain we would have arrived in time with the artillery and 200 men, and I believe it would have made a difference.

"As soon as it is possible, I will send you word how we are. Be at rest about the post. I have left it in a state to defend itself against all attacks without cannon, and I learn that they have finished all that remains to be done."

Col. Bouquet arrived at the camp at Loyalhanna on the 7th of Sept. He mentions this fact in a letter to Gen. Amherst written from that post, Sept. 17th, in which he reports the result of the reconnoisance of Maj. Grant. In this letter he explains at length the part he had in suggesting the expedition which was so disastrously carried out by Grant. In this letter is also given some account of the affairs about the camp, of interest in this place. He says:

"The day on which I arrived at the camp, which was the 7th, it was reported to me that we were surrounded by parties of Indians, several soldiers having been scalped, or made prisoners.

"Being obliged to have our cattle and our horses in the woods, our people could not guard or search for them, without being continually liable to fall into the hands of the enemy.

"Lieut. Col. Dagworthy and our Indians having not yet arrived, I ordered two companies each of 100 men to occupy the pathways and try to cut off the enemies in their ambush and release our prisoners." (15.)

Gen. Forbes to Col. Bouquet from Raystown, Sept. 23, 1758, where he had just heard of the report of Grant s defeat, says:

"I have sent Mr. Bassett back the length of Fort Loudoun in order to divide the troops from thence to Juniata, in small parties all along that road, who are to set it all to rights, and keep it so; and as the partys are all encamped within five or six miles one of another, they serve as escorts to the provisions and forage that is coming up, at the same time. * * * I understand by these officers that you have drawn the troops from your advanced post. * * * * I shall be glad to hear that all your people are in spirits, and keep so, and that Loyall Hannon will be soon past any insult without cannon. I shall soon be afraid to crowd you with provisions, nor would I wish to crowd the troops any faster up, until our magazines are thoroughly formed, if you have enough of troops for your own defense and compleating the roads; and I see the absolute necessity there is for my stay here some days, in order to carry on the transport of provisions and forage, which, without my constant attention, would fail directly. The road forward to the Ohio must be reconnoitered again in order to be sure of our further progress." (16.)

The great obstacle which retarded the progress of the army was that of a sufficient roadway. To make a passage-way however imperfect, was an undertaking of great difficulty. In many places, after it was made it answered the purpose but for a short time, so that forces had to be kept at work upon it constantly. New cuts were made, the angles changed, and the road-bed altered as necessity required. Some places along the side of the Laurel Hill were so steep that embankments had to be made for their support; at other places where the ground was marshy, the way became impassible with but little usage. "Autumnal rains, uncommonly heavy and persistent, had ruined the newly-cut road. On the mountains the torrents tore it up, and in the valleys the wheels of the wagons and cannon churned it into soft mud. The horses, overworked and underfed, were fast breaking down. The forest had little food for them, and they were forced to drag their own oats and corn, as well as supplies for the army, through two hundred miles of wilderness. In the wretched condition of the road this was no longer possible. The magazines of provisions formed at Raystown and Loyalhannon to support the army on its forward march were emptied faster than they could be filled. Early in October the elements relented; the clouds broke, the sky was bright again, and the sun shone out in splendor on mountains radiant in the livery of autumn. A gleam of hope revisited the heart of Forbes. It was but a flattering illusion. The sullen clouds returned, and a chill, impenetrable veil of mist and rain hid the mountains and the trees. Dejected nature wept and would not be comforted. Above, below, around, all was trickling, oozing, pattering, gushing. In the miserable encampments the starved horses stood steaming in the rain, and the men crouched, disgusted, under their dripping tents, while the drenched picket-guard in the neighboring forest paced dolefully through black mire and spongy mosses. The rain turned to snow; the descending flakes clung to the many-colored foliage, or melted from sight in the trench of half-liquid clay that was called a road. The wheels of the wagons sank in it to the hub, and to advance or retreat was alike impossible." (17.)

Sir John Sinclair was the Quartermaster-General. It is said of him that he was a petulant and irritable old soldier, who was a good type of those regular professional soldiers of his day, who had had their training in the wars on the continent. It was said that he found fault with everybody else, and would discharge volleys of oaths at all who met his disapproval. He, however, was brave and intrepid, and was with the troops in front whenever occasion demanded. It was his official duty to secure the transportation for the army; incident to this was the superintendence of the roads. But he must have had some quality of excellence that recommended him to the service; for he had occupied the same position under Braddock. By the provincials he was regarded as inefficient, and they did not like him, (18) for his arrogant ways. Forbes, himself, lost patience with him, and wrote confidentially to Bouquet that his only talent was for throwing everything into confusion. Among the orders and requisitions which he made in the line of his duty, when he had gone forward with the Virginians and other troops, to make the road over the main range of the Alleghenies, is the following memorandum: "Pickaxes, crows, and shovels; likewise more whiskey. Send me the newspapers and tell my black to send me a candlestick and half a loaf of sugar." (19.)

Gen. Forbes did not reach the camp at the Loyalhanna till about Nov. 1st. (20.) He had been carried most of the way in a litter. Fifty days elapsed from the time of his arrival at Bedford until he reached the Loyalhanna. It was determined at a council of war held after his arrival here not to advance further that season. The weather had become cold, and the summits of the mountains were white with snow. This determination, however, was suddenly changed, as the result of information obtained from various sources touching the actual condition of affairs at Fort Duquesne. It was learnt conclusively, that the French were wanting provisions, that they were weak in number, and that the Indians had left them. It was thereupon concluded to proceed.

Col. Washington had so earnestly requested the privilege of leading the army with his Virginians, that his request was granted; and he and his men under Col. Armstrong with the Pennsylvanians were intrusted with that duty. He was then but a young man, but already a beloved leader of his men. Virginia had intrusted to him her two regiments, consisting of about 1900. Part of this force were clothed in the hunting shirt and Indian blanket, which least impeded their progress through the forest. He himself gave as a reason why he should have this honor that he had "a long intimacy with these woods, and with all the passes and difficulties." (21.)

He and his provincials then, as the advance of the army, set out to open the way. On the 12th of Nov., about three miles from the camp his men fell in with a number of the enemy, and in the attack, killed one man, and took three prisoners. Among the latter was one Johnson, an Englishman, who had been captured by the Indians in Lancaster county, from whom was derived full and correct information of the state of things at Fort Duquesne. On this occasion occurred one of the most memorable of things that can be narrated about Fort Ligonier. (22)

We here allude to the engagement which occurred among the provincial troops by a misunderstanding of orders, in which Washington ran the greatest risk of death. There has never been made public until lately a consistent narrative of this affair. Owing to Washington's reluctance to speak of himself and of his military career, all the published reports lacked a certain element of credibility. It was however, conceded on all sides that the occurrence was remarkable, and that the remembrance of it always remained fresh in the mind of Washington. The best known authority for the affair was that which was traceable to Gordon's History of Penn'a. From the statement there made it appeared that Col. Washington's detachment was engaged on the road several miles from the fort, and that the noise of arms being heard at the fort it was conjectured that his detachment was attacked; and that thereupon Col. Mercer, with some Virginians, was sent to his assistance; that the two parties approaching in the dusk of the evening, mistook each other for enemies; and that a number of shots were exchanged, by which some of the Virginians were killed.

From the conversation between Washington and the Hon. Wm. Findley, Member of Congress from the Westmoreland district, which has been preserved, the popular version has obtained. Whatever allowance may be made for the literal accuracy of this account, owing to the lapse of time from its narration until its publication, it is certain that it contains substantially the essential and elementary germ of fact which clothes this circumstance with so much interest A deviation in minor particulars from the more authentic account, here referred to, does not detract from its merits. The association of one command with the other, is excusable when we remember that Mr. Findley put his recollections on paper near twenty years after Washington's death, and then only from memory.

But we have from late sources the version given by Washington himself of this affair. In an article published in Scribner's Magazine for May, 1893, there is reproduced some account of the western frontier wars in which Washington participated, from the manuscript of Washington himself. In prefacing the extracts from this manuscript, Mr. Henry G. Pickering, in whose family the original manuscript is still preserved, says that "It was the purpose of Col. David Humphreys, a member of Washington's military staff in the latter part of the revolutionary war, to write the life of Washington; and it would seem, that at his request Washington prepared the narrative, the connected part of which is given in the article referred to. This narrative is in autograph, covering some ten pages of manuscript of folio size, and is in part responsive to detailed and numbered questions put by Col. Humphreys. * * * * There are frequent interlineations and erasures, and the words "I" and "me," in nearly every instance where they occur, are changed to the initials "G. W.," by the revision. It was recently read, by permission, before the Mass. Historical Society, but it has never been printed, [prior to the article referred to], nor, it is believed, have any extracts from it been ever given to the public. Certain incidents described in it, such as the instance of grave peril in which Washington's life was placed in one of the engagements, are of original historical interest, but the permanent value of the narrative is in its authoritative source, and the unchanged form in which it has been transmitted.

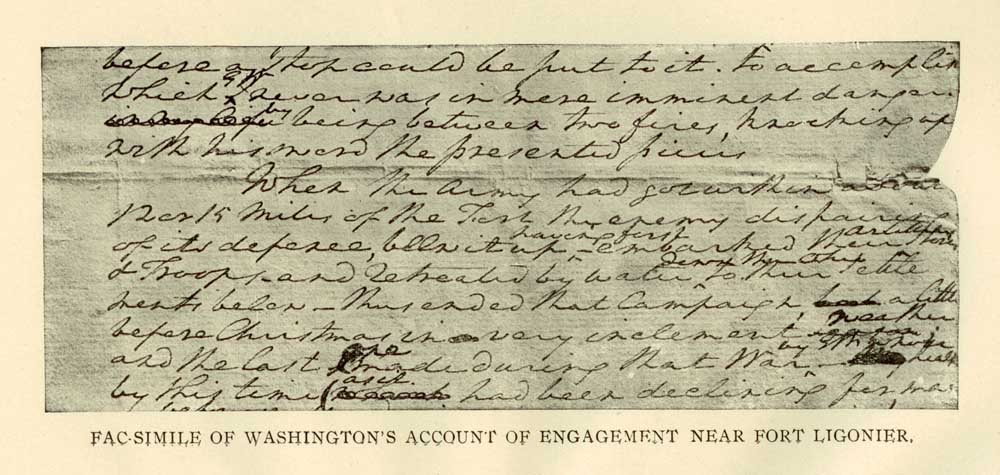

Facsimile of Washington's Account of Engagement Near Fort Ligonier.

The following is a literal transcription of the article:

"But the war by this time raging in another quarter of the continent, all applications were unheeded till the year 1758, when an expedition against Fort Duquesne was concerted and undertaken under the conduct of Genl. Forbes; who though a brave and good officer, was so much debilitated by bad health, and so illy supplied with the means to carry on the expedition, that it was November before the troops got to Loyalhanning fifty or sixty miles from Fort Duquesne, and even then was on the very point of abandoning the expedition when some seasonable supplies arriving, the army was formed into three brigades—took up its march—and moved forward; the brigade commanded by G. W. being the leading one. Previous to this, and during the time the army lay at Loyalhanning, a circumstance occurred which involved the life of G. W. in as much jeopardy as it has ever been before or since.

"The enemy sent out a large detachment to reconnoitre our camp, and to ascertain our strength; in consequence of intelligence that they were within two miles of the camp a party commanded by Lieut. Col. Mercer, of the Virginia Line (a gallant and good officer) was sent to dislodge them, between whom, a severe conflict and hot firing ensued, which lasting sometime and appearing to approach the camp, it was conceived that our party was yielding the ground, upon which G. W. with permission of the Genl. called (per dispatch) for volunteers and immediately marched at their head, to sustain, as was conjectured, the retiring troops. Led on by the firing till he came within less than half a mile, and it ceasing, he detached scouts to investigate the cause, and to communicate his approach to his friend Col. Mercer, advancing slowly in the meantime. But it being near dusk, and the intelligence not having been fully disseminated among Col. Mercer's corps, and they taking us for the enemy who bad retreated approaching in another direction, commenced a heavy fire upon the relieving party which drew fire in return in spite of all the exertions of the officers, one of whom, and several privates were killed and many wounded before a stop could be put to it, to accomplish which G. W. never was in more imminent danger, by being between two fires, knocking up with his sword the presented pieces."

On the 13th, Col. Armstrong, who had proved his skill in leading troops expeditiously through the woods, was sent out to the assistance of Washington with 1,000 men. Armstrong was the senior officer of the Pennsylvania forces, and was next in command under Bouquet. These two bodies of provincials, as it would appear, cooperated together in the front; sometimes detachments of the one would be passed on the road by detachments of the other, and so again as the occasion required. The army progressed slowly; the weather was rainy; the road miserably bad. A number of friendly Indians were kept out as scouts; and every precaution was taken to guard against surprise.

The force for this purpose specially consisted of 2,500 men picked out. That the men might be restricted as little as possible in their movements, they went without tents or baggage, and with a light train of artillery expecting to meet the enemy, and ready to determine the result by a battle.

On the 17th of Nov., Washington was at Bushy Run. On the 18th, Armstrong is reported within 17 miles of Fort Duquesne, where he bad thrown up intrenchments. Gen. Forbes himself followed on the 17th from Ligonier with 4,300 effective men—having left strong garrisons and supplies at Ligonier and Bedford.

At every stopping place they all resorted to every precaution. On the 19th, Washington left Armstrong (who in the meantime had come up to him) to wait for the Highlanders, and, taking the lead, with vigilance proceeded towards the fort. On the 24th, Forbes encamped his whole army about Turtle Creek, 10 or 12 miles from Fort Duquesne. Here the word was brought by the Indian scouts who had advanced to within sight of the fort, that the French had abandoned the place and that the structures were on fire. This report was soon confirmed. A company of cavalry under Capt. Hazlet was sent forward to extinguish the fire and save as much as possible, but they were too late. Preparations had been made by the French to withdraw when it was seen that they could offer no resistance. They had made ready to destroy their works, and after setting fire to everything that would burn, they withdrew with the rest of their munitions and cannons, some going down the Ohio, and the Commandant with the most of his forces going up the Allegheny to Fort Machault. The whole of the English hurried forward and on Saturday, 25th of Nov., 1758, took possession of the site of Fort Duquesne, and thenceforth the place was held by those of Saxon blood.

It is true the old Fort Duquesne was but a heap of ruins when the army came to take possession of it; nevertheless, the campaign of Forbes was eminently successful. He took possession of this fortress to which the eyes of the civilized world were directed, without an engagement, the fruits of his labors falling into his hands by reason of his careful and masterful arrangements, his skillful assistants, and his ample preparations which won him a bloodless victory, and the English race one of its greatest achievements.

On the next day, Nov. 26th, Gen. Forbes, making report to Gov. Denny of the success of the expedition, added: "I must beg that you recommend to your Assembly the building of a blockhouse and saw mill upon the Kiskiminetas near the Loyalhanna, as a thing of the utmost consequence to the province, if they had any intention of profiting by this acquisition." (23.)

The importance of Fort Ligonier as a military position was apparent, even before this event. Forbes, in a letter to the Governor from Raystown, Oct. 22, 1758, when the immediate success of their expedition was uncertain, says that, whether their attempt on Fort Duquesne should be successful or not, the chain of forts from the Loyalhanna to Carlisle ought to be garrisoned, besides those on the other side of the Susquehanna. Of the number required to garrison these posts, he estimates that there should be 300 at Loyalhanna, and 200 at Raystown. (24.)

Forbes set out from Pittsburgh to return, on the 3rd of Dec. (25.) On the 8th, Frederick Post came to Ligonier where he found the General very sick. He expected to leave every day, but still continued to be too ill to be moved. On the 14th, he (the General) intended to go, but his horses could not be found. They thought the Indians had carried them off. They hunted all day for the horses, but could not find them. "On the 16th, Mr. Hays," he says, "being hunting, was so lucky as to find the General's horses, and brought them home; for which the General was very thankful to him." Here they all remained till the holidays. Under date, Dec. 25th, Post says, "The people in the camp prepared for a Christmas frolic, but I kept Christmas in the woods by myself." This was the first Christmas celebrated by the English in that region. On the 27th, he says, "Towards noon the General set out; which caused great joy among the garrison, which had hitherto lain in tents, but now being a small company, could be comfortably lodged. It snowed the whole day."

During the latter part of the year of 1758 and the early part of 1759, there were busy times about the fort, as it was in the direct line of communication to Fort Pitt from the east. Of necessity there was much movement on the military road during this time, and this post from its location was the most important relay station west of Bedford. It is not probable that any particular body of troops remained here continuously for any length of time. Part of the time, we know, the detachments of the Pennsylvania provincials were here; sometimes there were Virginians, but most of the time—and, after the regular soldiers were withdrawn from their campaign, all the time—the garrison was composed of Royal Americans. It would further appear that for most of the time the senior officer who happened to be located here, was the one in command, although the commandant at Fort Pitt was superior officer in this department. Col. Hugh Mercer was left in charge at Fort Pitt, and remained there until the arrival of Gen. Stanwix, who came out in the spring of 1759 to superintend the erection of the more permanent fortress at that place. Mercer himself was at Ligonier when Forbes took possession of Fort Duquesne; as from here he communicated the successes of the army in a letter to Gov. Denny (26), Dec. 3, 1758.

When the French abandoned Fort Duquesne, their Commandant, De Ligneris retired to Fort Machault (Venango). They still had some influence over some of the Indians of the northwest; and that vigilant officer used these to good advantage. From Venango, and from Indian towns along the Allegheny and streams westward, parties of these barbarians led by the French Canadians, made inroads constantly on the out posts of the Province, and were always on the alert to waylay and harass the convoys on the road. Many reports are made of their depredations, even after the French abandoned Venango, in Aug., 1759.

The first camp at the Loyalhanna was doubtless made after the fashion of those others on the line of advance of Bouquet; and of necessity was made before the fort was built. Col. Jos. Shippen, in a letter from Raystown describing the works there, says: "We have a good stockade fort built here with several convenient and large store-houses. Our camps are all secured with a good breast work and a small ditch on the outside." (27.)

In the report of Grant's defeat by Montcalm he says that the defeated soldiers "were pursued up to a new fort, called Royal hannon, which they [the English] are building." (28.)

About the first mention made of the place by the French was on the occasion of the arrival there of Bouquet's advance, at which time it is reported "that a fort has been built of piece upon piece, and one saw mill." (29.)

From the same sources reports were made that the works at Loyalhanna were still in process of construction in the spring of 1759. (30.)

The number of troops here during the winter of 1758 and throughout 1759, must have been considerable. This was necessary not only for the protection of the post but as a support to Fort Duquesne; for there were fears and uncertainties as to the plans of the enemy. Col. Mercer, in Sept. (1759), states that "the difficulty of supplying the army at Pittsburgh obliges the General to keep more of the troops at Ligonier and Bedford than he would choose." (31.) At that date, Col. Armstrong was at Ligonier, and was expected to remain some weeks longer. Prior to that time, however, Col. Adam Stephen of the Va. provincials was at least for the time being in command at Ligonier. Under date, from this place, July 7th, (1759), Col. Stephen reports to Gen. Stanwix the particulars of an engagement that occurred the day before. He reports as follows: (32.)

"Yesterday about one o'clock the Scouts and Hunters returned to camp & reported that they had not seen the least sign of the Enemy about; upon which, in Compliance with Maj. Tulliken's request, I sent Lt. Blane with the R. Americans to Bedford, and as the party was but small, ordered a Sergt. & Eighteen chosen Woodsmen, to conduct him through the Woods, to the foot of Laurel Hill on the West side, with directions to return to Camp without touching the Road.

"About three Quarters of an hour after the Detachmt. had marched, the Enemy made an attempt to Surprise this Post. I cannot ascertain their numbers, but am certain they are considerably superior to ours.

"At first I imagined the Enemy only intended to amuse the Garrison whilst they were engaging with Lt. Blane's Party, but finding the place invested in an instant & the Enemy rush pretty briskly, I began to entertain hopes of their safety, and was only anxious for the Sergt. and Eighteen men.

"The Enemy made an effort from every Quarter, but the fire on the first Redoubt was the hottest, in it Capt. Jones was killed.

"We are extremely obliged to Lt. Mitchelson, of the Artillery, for his Vigilence & application. After a few well placed shells and a brisk fire from the Works, the Enemy retired into the skirts of the Woods, and continued their fire at a distance, till night.

"The Sergt. (Packet, of the Virginians) returned about sunset without seeing an Enemy until he came within sight of the Fort. The party behaved well, fought until they had orders to retreat & got in without the loss of a man.

"The Enemy never molested us in the night. Small Parties of them have shown themselves in the skirts of the Woods & fired at a distance without doing us any hurt.

"We were happy in saving the Bullock guard & Cattle & all the horses employed in the public Service were luckily returned to Bedford.

"I have not heard from Pittsburgh since the first inst., where Capts. Woodward & Morgan then arrived with a detachment of 230 men, having under their care Eighty horse load of flour.

"P. S. We have only Capt. Jones killed & three men wounded & flatter ourselves that their loss is considerable."

On the 17th of the same month, Col. Mercer reporting to Gov. Denny from Pittsburgh, says: "Half the party that attacked Ligonier was returned (to Venango) without prisoners or scalps; they had by their own account, one Indian killed and one wounded." (33.) Whether this has any allusion to the attack reported by Colonel Stephen, is left only to inference.

Then for a time when the French were making ready to leave Venango and after they had determined to do so, there are less frequent reports of attacks either on the posts or convoys; but there was no safety for those that were on the roads alone or unprotected. In August, Col. Mercer writes to Gov. Denny from Pittsburgh: "We are likely to have little trouble from the enemy this way, for their Indians have dropped off to a very few who, in small parties, lie about Ligonier, and this place, serving as spies, and now and then taking a scalp or prisoner." (34.)

Later in the same month as part of the intelligence received by the Council from Pittsburgh, is the following from Col. Mercer: "In the evening 11th of Aug., 1759, a Delaware Indian informed me that 9 Indians of their nation from Venango had been in the road below Ligonier, and taken an Englishman prisoner, but that he had made his escape from them in the night." (35.)

Col. Mercer in a report to Gov. Denny from Pittsburgh, Sept. 15th, 1759, says that "the difficulty of supplying the army here obliges the General to keep more of the troops at Ligonier and Bedford than he would choose; the remainder of the Virginia regiment joins us next week. Col. Armstrong remains some weeks at Ligonier, and the greater part of my battalion will be divided along the communication to Carlisle."

At the latter end of 1759, Gen. Stanwix, in command of this department, reported to Gov. Hamilton that, as the Assembly had directed the disbandment of their troops, he had ordered "all the Pennsylvanians this side of the mountain, viz., at Pittsburgh. Wetherhold, Fort Ligonier, and Stoney Creek, to march immediately to Lancaster; to be paid and broke." Having sent the Virginians home at the request of the Virginia authorities for service on their frontiers, the posts here were garrisoned by the Royal Americans. (36.) In the winter of 1760 and 1761, Col. Vaughan's regiment were garrisoned on the communication. (37.)

Little occurred to disturb the ordinary routine about these frontier posts for several years. The line of forts which had been established by the French along the Allegheny, and on the lakes, fell into the hands of the English by the terms of their treaty. The French being defeated, relinquished their possessions in America; and these posts were garrisoned by the British government. Venango, LeBoeuf, Presqu' Isle were occupied soon after the fall of Fort Duquesne.

In 1763 occurred Pontiac's War. This war was brought about by the exertions of this one great chief, and from him it is often called Pontiac's Conspiracy. His scheme was to attack all the English posts, and, after massacreing the garrisons to destroy the works. With this war, Fort Ligonier is inseparably connected.

In 1763 the English settlements did not extend beyond the Alleghenies. In Pennsylvania, Bedford might be regarded as the extreme verge of the frontier. From Bedford to Fort Pitt was about 100 miles; Fort Ligonier lay nearly midway. Each of these was a mere speck in the deep, interminable forests. Tier after tier of mountains lay between them, and they were connected by the one narrow road winding along hills and through sunless valleys. Little clearings appeared around these posts; among the stumps and dead trees within sight of the forts, the garrison and a few settlers, themselves mostly soldiers, raised vegetables and a little grain. The houses and cabins for the most part were within the stockades. The garrisons were mainly regulars, belonging to the Royal American regiment. Their life was very monotonous. Along these borders there was, at that time, little to excite their alarm or uneasiness. Some Indians frequented Fort Pitt, and settlers were coming in; but the sight of strange faces was rare. Occasionally news was brought by express-riders; but the life of those who were obliged to perform garrison duty at these posts, was devoid of excitement and monotonous in the extreme.

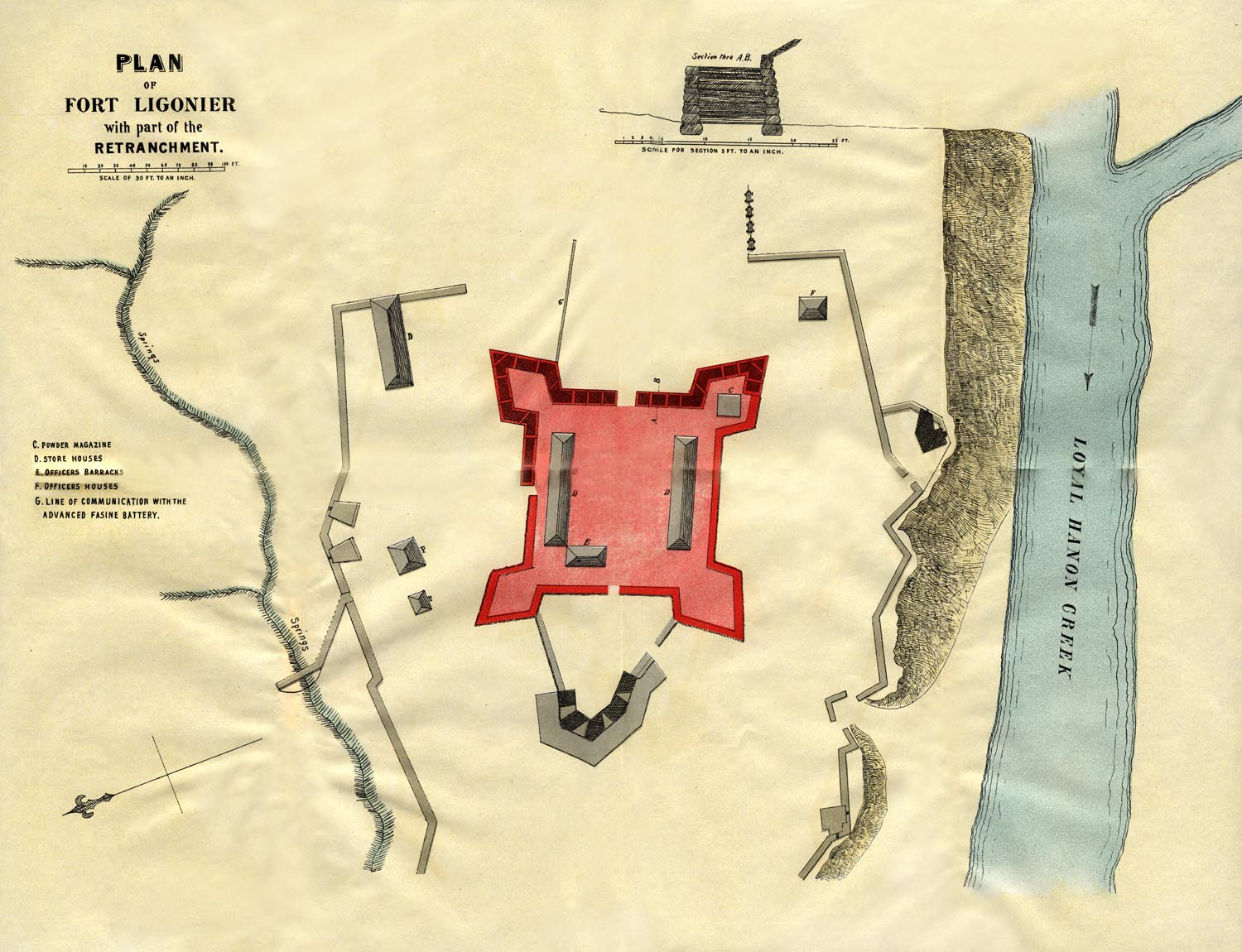

Plan of Fort Ligonier with Part of the Retranchment.

In the latter part of May, 1763, Capt. Ecuyer wrote to Col. Bouquet, from Pittsburgh, that he believed the Indian affair, from the evidences around him, was general, and he trembled for the out-posts. (38.) At that time settlers had been killed near the fort, and there were unmistakable signs of the Indians who had been regarded friendly, having deserted their villages, and taken to the war path.

Fort Ligonier being on the line of relief to Fort Pitt, it became necessary, for the successful accomplishment of their scheme, that it should fall; for no war had been more carefully planned, no campaign more skillfully laid out, or better executed than that which had its origin in the brain of the savage Pontiac, Chief of the Ottaways. In each locality its execution was carried out by the principal warrior or chief of that particular region. All orders were executed without dissent, and with implicit obedience.

The Indians well knew that the destruction of Fort Pitt would avail them nothing permanently unless Fort Ligonier was likewise destroyed. Besides, there were at Ligonier some stores and munitions which would be of use to them. These two posts gone, all the whites to the Allegheny Mountains would have been murdered. For when they took a post, its capture was followed by the immediate killing of its inmates, or by the torture of those who escaped speedy death. It was only when the garrison was strong enough to make terms, that it was otherwise.

The Indians, therefore, at about the same time at which they began their operations at Fort Pitt, appeared about Fort Ligonier; for one morning a volley of bullets was sent among the garrison, with no other effect, however, than killing a few horses. Again an attack was made, about the middle of June, by a large body of Indians who fired upon it with great fury and pertinacity, but were beaten off after a hard day's fighting.

The relief of these outposts was entrusted to Col. Bouquet, and the particulars of his expedition are given in another place. He was now doing what he could to keep up the line of communication and to organize a force fit to penetrate to Fort Pitt and relieve the frontier settlements and the posts. He was encamped near Carlisle, on the 3d of July, 1759, when he heard of the loss of Presqu' Isle, Le Boeuf and Venango. (39.)

Fort Ligonier was then commanded by Lieut. Blane, of the Royal American regiment. Blane had been at this post for a number of years. Capt. Lewis Ourry, of the same regiment, was in command at Bedford. These officers kept up a precarious correspondence with each other by means of express-riders. This service was dangerous to the last degree, and soon became impracticable. The substance of a letter from Col. George Armstrong to Gov. Hamilton, from Carlisle, June 16th, is "That Blane, commander at Ligonier, has not had a scrape from Pittsburgh, nor even any verbal intelligence since the second express which went to there from Phila.—the third express taking the route by Fort Cumberland. That circumstance, with the loss of a man at Ligonier, who going out on the 14th instant to bring his horse was picked up (so termed) near that place, gives Blane, with many others, reason to conjecture that Pittsburgh is invested and the communication cut off."

The condition of affairs about Fort Ligonier from about the 1st of June until the post was relieved by the arrival of the army, is well disclosed in the correspondence of Col. Bouquet, which covers this period. The actors thus tell their own stories. This correspondence has been incorporated into the body of the historical work treating of this war by Francis Parkman; and from that work we have taken at length, whenever necessary, for the narrative pertaining to this fort. (41.)

The following extracts from the letters of Lieut. Blane, will show his position; though, when his affairs were at the worst, nothing was heard from him, as all his messengers were killed. On the 4th of June he writes: "Thursday last my garrison was attacked by a body of Indians, about five in the morning; but as they only fired upon us from the skirts of the woods, I contented myself with giving them three cheers, without spending a single shot upon them. But as they still continued their popping upon the side next the town, I sent the sergeant of the Royal Americans, with a proper detachment, to fire the houses, which effectually disappointed them in their plans." (42.)

On the 17th, he writes to Bouquet: "I hope soon to see yourself, and live in daily hopes of a reênforcement. * * * * * Sunday last, a man straggling out was killed by the Indians, and Monday night three of them got under an out-house, but were discovered. The darkness secured them their retreat. * * * I believe the communication between Fort Pitt and this is entirely cut off, having heard nothing from them since the 30th of May, though two expresses have gone from Bedford by this post."

On the 28th, he explains that he has not been able to report for some time, the road having been completely closed by the enemy. "On the 21st," he continues, "the Indians made a second attempt in a very serious manner, for near two hours, but with the like success as the first. They began with attempting to cut off the retreat of a small party of fifteen men, who, from their impatience to come at four Indians who showed themselves, in a great measure forced me to let them out. In the evening, I think above a hundred lay in ambush by the side of the creek, about four hundred yards from the fort; and just as the party was returning pretty near where they lay they rushed out, when they undoubtedly would have succeeded had it not been for a deep morass which intervened. Immediately after, they began their attack; and I dare say they fired upwards of one thousand shot. Nobody received any damage So far, my good fortune in dangers still attends me."

By some means, Blane got word through to Capt. Ourry, of the fall of Presqu' Isle and the two other posts; for Bouquet reports to Gen. Amherst, July 3d, the news which he had received from Capt. Ourry, who had received it from Blane.Knowing the straits in which Lieut. Blane and his men were, and having fears that they could not hold out without relief Capt. Ourry sent out from Bedford, a party of twenty volunteers, all good woodsmen, who reached Ligonier safely. This fact is mentioned in the Account of Bouquet's Expedition, but the particular date is not given. It was probably towards latter part of June. (43.)

While Bouquet lay at Carlisle, and the tidings were more and more gloomy, his anxieties centered on Fort Ligonier. If that post should fall, his force would probably not be able to proceed, and his would be the fate of Braddock. In the words of the authentic narrative, —The fort was in the greatest danger of falling into the hands of the enemy, before the army could reach it, the stockade being very bad, and the garrison extremely weak, they had attacked it vigorously, but had been repulsed by the bravery and good conduct of Lieut. Blane. The preservation of that post was of the utmost consequence on account of its situation and the military stores it contained, which, if the enemy could have got possession of, would have enabled them to continue their attack upon Fort Pitt and reduce the army to the greatest straits.

For an object of such importance, every risk was to be run. He therefore resolved at an attempt to throw a reenforcement into the fort. Thirty of the best Highlanders were chosen, furnished with guides, and ordered to push forward with the utmost speed, avoiding the road, traveling by night by unfrequented paths, and lying close by day. The attempt succeeded. After resting several days at Bedford, where Ourry was expecting an attack, they again set out. They were not discovered by the enemy until they came within sight of the fort, which was beset by the savages. They received a volley as they made for the gate; but entered safely to the unspeakable relief of Blane and his beleagured men. (44.)

When Bouquet reached Bedford, on the 25th of July, Ourry reported to him that for several weeks nothing had been heard from the westward, every messenger having been killed and the communication completely cut off. By the last intelligence Fort Pitt had been surrounded by Indians, and daily threatened with a general attack.

The condition of those at Fort Ligonier during those last days must have been miserable in the extreme. Cooped up in the fort, and blockaded for several weeks, they could neither hear from the outside world nor could they convey any information. We can therefore well imagine that it was with great joy they caught the first glimpses of the red coats emerging out of the dark laurel bushes, as they first appeared coming down the slope from the base of the Laurel Hill. What greetings there must have been, when on the second of August, the little army with its convoy reached the stockade at Ligonier.

Bouquet, leaving a sufficient garrison and most of his provisions and cattle at Fort Ligonier, proceeded to the relief of Fort Pitt. The savages vanished when he came up. He left the fort on the 4th of August, and on the 5th and 6th had the engagement with the Indians at Bushy Run, an account of which has been given elsewhere.

Col. Bouquet, not having a sufficient force to penetrate into the Indian country, was obliged to restrain his operations and devote his means and attention to supplying the forts with provisions, ammunition and other necessaries, protecting them against surprise, and garrisoning them with his men, until the next year, when with new forces he advanced into the Ohio country.

The troops who had garrisoned these posts during this terrible time, had, for the most part, come out with Forbes in 1758. To these, life was becoming a burden. And it was no wonder. They were all tired of this service: and we can read with marked interest the series of complaints with which the commanding officers at these posts worried the ears of Col. Bouquet. Thus Lieut. Blane, after congratulating Bouquet on his recent victory at Bushy Run, adds: "I have now to beg that I may not be left any longer in this forlorn way for I can assure you the fatigue I have gone through begins to get the better of me. I must therefore beg that you will appoint me by the return of the convoy a proper garrison * * *My present situation is fifty times worse than ever." And again, on the 17th of September: "I must beg leave to recommend to your particular attention the sick soldiers here; as there is neither surgeon nor medicine, it would really be charity to order them up. I must also beg leave to ask what you intend to do with the poor starved militia, who have neither shirts, shoes, nor anything else. I am sorry you can do nothing for the poor inhabitants. * * I really get heartily tired of this post." He endured it some two months more, and then breaks out again on the 24th of Nov.: "I intend going home by the first opportunity, being pretty much tired of the service that's so little worth any mans' time; and the more so, as I cannot but think that I have been so particularly unlucky in it." (45.)

We often read in the accounts of those times of the difficulty the officers had in keeping their soldiers from deserting. There was indeed little wonder that these should do so. Their existence on the frontier during those perilous times was pitiable in the extreme. Parkman, repeating after Smith, calls them military hermits. As an example of the discontent which prevailed among officers and men who had now for well nigh seven years been isolated from civilization, the example of Capt. Ecuyer may well be taken. He writes to Bouquet from Bedford—as Mr. Parkman says—on the 13th of Nov. (1763). Like other officers on the frontier, he complains of the settlers, who, notwithstanding their fear of the enemy, always did their best to shelter deserters; and he gives a list of eighteen soldiers who had deserted within five days: "I have been twenty-two years in service, and I never in my life saw any thing equal to it—a gang of mutineers, bandits, cut-throats, especially the grenadiers. I have been obliged, after all the patience imaginable, to have two of them whipped on the spot, without court martial. One wanted to kill the sergeant and the other wanted to kill me. * * * * For God's sake, let me go and raise cabbages. You can do it if you will, and I shall thank you eternally for it. Don't refuse, I beg you. Besides, my health is not very good, and I don't know if I can go up again to Fort Pitt with this convoy."

An extract from a letter of Capt. Ecuyer to Col. Bouquet from Fort Pitt, April 23d, 1763, deserves to be given. "Before the arrival of your letter I had sent four horses to Ligonier, they have returned with a wagon loaded with iron, harness and tools. I have sent an order to Mr. Blane to send to me all the King's horses, having great need of them here, for the boats and for the gardens. But he replied that he has not any, and that the horses which he has belong to himself, and that be had arranged with you on this subject when you came down. I believe that living so long at this post has made him believe at last that the place belongs to him." (46.)

The following letters of Colonel Henry Bouquet, written from Fort Pitt in September of 1763, were published for the first time in the Magazine of Western History, for October, 1885: (47.)

"Fort Pitt, 15th September, 1763.

"Sir: I received the 10th instant your letters of the fifth, eighth and ninth, with the return of Ligonier. The King's company observes that you have not given credit for some barrels of flour and a strayed ox, which will of course increase the loss of your stores. However, considering all the circumstances, it will be found very moderate. The garrisons must supply themselves with firewood in the best manner they can, as the General does not make any allowance for that article; you might have the trees cut now and hauled in when you have horses, as I find it a saving not to cut it small in the woods."Can the inhabitants of Ligonier imagine that the King will pay their houses destroyed for the defence of the fort? At that rate he must pay likewise for two or three hundred pulled down at this post, which would be absurd, as those people had only the use and not the property of them, having never been permitted either to sell or rent them, but obliged to deliver them to the King, whenever they left them.

"As to their furniture, it is their fault if they have lost it. They might have brought it in or near the fort.

"What cattle has been used for the garrison will of course be paid for, but what has been killed or taken by the enemy I see nothing left to them but to petition the General to take their case into consideration. I am very sorry for their misfortune, and would assist them if I had it in my power, but it is really not.

"The orders forbidding any importation of goods are given by Sir Jeffrey Amherst. However, upon sending me a list of what may be absolutely wanted, I shall take upon me to grant a permit. One suttler would be sufficient for that post. We do very well here since we have none at all.

"I am sorry to have to acquaint you that Lieutenants Carre and Potts are included in the reduction, though all the ensigns remain. I shall, with great pleasure, take the first opportunity to recommend you to the General for some place, if a staff is established in the garrisons of this continent.

I am, sir, your obedient and humble servant,

H. BOUQUET."______

"Fort Pitt, 30th September, 1763.

"Dear Sir: I received your letter of the twentieth with returns for September."Major Campbell will change your garrison and, however disagreeable those things are, you must be persuaded that we do what we can, and not what we would choose.

"If the ship carpenters now here are not sent to the lakes you may retain them a couple of days to fit out barracks for about fifty men, for I don't think we shall have more to spare. Blankets are certainly very necessary, and I will send them down for winter service. As to the other article, I cannot help you at present in that. You must keep two horses going, and I'll send you some Indian corn. I wish Major Campbell could give you some assistance to cut trees at least, but I know how difficult it is upon a march to do those things.

"You will not forget to send the rice and axes you received from Bedford for this post with the seeds.

I am, dear sir, your most obedient servant,

H. BOUQUET.

"Lieutenant Blane"The original of this letter, from Colonel Henry Bouquet to Lieutenant Blane, who was stationed at Fort Ligonier, is among the papers of General Arthur St. Clair, purchased by the State of Ohio and preserved at Columbus. It was copied for The Magazine of Western History, by Mr. A. A. Graham, secretary of the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society, at Columbus. It was written from Fort Pitt after battle of Bushy Run.

Capt. Ecuyer writes to Col. Bouquet from Bedford, November 8th, 1763, stating: "We arrived here on the 4th of the month and departed the 9th. I do not know when we will arrive at Ligonier, for the roads are terrible for the chariots. * * * * The soldiers which are here (Bedford) and at Ligonier in garrison complained bitterly that they are not provided for, and I have no money to give them." (48.)

The soldiers on the line of the communication were busy keeping the way open, guarding the convoys and hastening to relief whenever required. Fort Pitt was kept up until 1772, after which a corporal and a few men only were kept at fort. The next year Richard Penn advised that a small garrison should be kept there as a protection from the Indians. It is not known, therefore, when Fort Ligonier ceased to be garrisoned by the Royal Americans, but there is presumption of the strongest character that about 1767 to 1769 small detachments of soldiers under the Proprietary's government were posted here. It was, however, stated officially, January 30th, 1775, that, "since the conclusion of the last war [French and Indian War, 1754 to 1763], no forts or places of have been kept up within this government," (49) and thus the duties of such as were stationed at these posts, it is probably, were more of civil or police character than of a military character.

During the summer of 1764 Bouquet was occupied in organizing an expedition against the Ohio Indians, as it was too late in the season, and he had suffered too much in the campaign of the preceding year to think of advancing farther until his forces were recruited. He successfully accomplished the object of his labors.

In the latter part of August, 1764, the Indians made a raid near Bedford, and killed near that place one Isaac Stimble, an industrious inhabitant of Ligonier, took some horses loaded with merchants' goods and shot some cattle, after Col. Reed's [Reid] detachment had passed that post. (50.)

From the close of Pontiac's War and the treaty of 1764 with the Ohio Indians, there was no general war waged on the part of the savages upon the outposts of Pennsylvania for some time succeeding. The land office was opened to settlers in Pennsylvania in the spring of 1769, in pursuance of the of the treaty of 1768. From that period settlers came hither in great numbers. In an incredible short period of time, lands were located and settlers were occupying them beyond the bounds of what we now regard as Westmoreland county, on the north extending beyond the Conemaugh. Lands could not betaken farther northward than the limits of the purchase, which was a straight line from where now the counties of Indiana, Clearfield and Cambria meet, at a point called Cherry Tree to Kittanning on the Allegheny river. It is not probable however, that more than a very few isolated settlers occupied any lands very far northward of the Conemaugh until several years after the opening of the office, (1769).

From that time it was not long until the county of Westmoreland was erected out of Bedford for the convenience of the inhabitants of this region. This event occurred February 26th, 1773.

During this time the interests of the Penns in this part of their Province were entrusted to some gentlemen of high repute and of great integrity. Of these, one of the chiefest was Arthur St. Clair. St. Clair, afterward a distinguished general in the War of the Revolution, and the first governor of the Western Territory, was at that time designated Captain, although his duties were chiefly of a civil character. By birth a Scot, the descendant of an ancient and distinguished family, he was by nature inclined to a military life. Having gotten an ensign's commission in the army which Britain sent out in 1758 to join in the war against the French in America, he had served in the expedition against Canada under Wolfe, had married in Boston May 14th, 1760, had resigned his commission April 16th, 1762, and within a few years after, had become interested as the agent of the Penns in the West. It is probable that he was at Fort Ligonier in some kind of service some time before 1769. In a warrant granted to him for a certain body of land in Ligonier township, it was recited that he was in command of the post at Ligonier in 1769 at the date of the opening of the land office. What the nature of the service of those agents at these posts was after the withdrawal of the regular garrisons about 1765, we have, at present, no accurate means of determining. When the Commander-in-Chief of the British army abandoned Fort Pitt as a military post at a later period, the Penns kept a few men there, as we have seen, to take care of the public property.

St. Clair was appointed Surveyor for the District of Cumberland county, April 5th, 1770, and commissioned Justice of the Court and a Member of the Proprietary Council for that county. At that time Western Pennsylvania was within the civil jurisdiction of Cumberland, and remained in it until Bedford county was established, March 9th, 1771 at which time he was appointed a Justice of the County Courts, Prothonotary, Register and Recorder of Bedford county (March 11 and 12). When Westmoreland county was erected, February 1773, he was appointed and commissioned to the same in that county. In 1771, St. Clair, with Moses Maclean, Esq., had run a meridian line west of the meridian of Pittsburgh and his familiarity with this region and his knowledge derived from an execution of this commission, made him, from this circumstance especially, of advantage to the Penns in their contention with the Governor of Virginia, which was now about culminating.

From these circumstances it is probable that the post of Ligonier was kept up in a kind of way from 1765 until about 1770 by the Proprietary government, and that St. Clair had charge of it a part of the time. He is, in the correspondence of 1773 and 1774, addressed as "Captain" by the Governor; it is known that he had not borne that title in the British service. (51.)

His duties hereabouts were arduous and constant, among which was the very responsible obligation resting on him to keep the Indian tribes at peace with the Province.

The year 1774 was an eventful one in the annals of Western Pennsylvania. In that year occurred the frontier war known as Dunmore's War, the last one in which the colonists engaged with the mother country as her subjects. The war burst upon the southwestern frontiers with fury. Instantaneously, as it were, the whole of that region was in consternation and alarm. During this time Ligonier was the center of Pennsylvania influence for all that region which acknowledged the legitimate authority of this Province.

The conflict of jurisdiction between the authorities of Pennsylvania and of Virginia now partook of the condition of civil war. Lord Dunmore, the Tory Governor of Virginia, by his agents, some of whom were desperate and lawless characters, asserted his claims with arms. In various sections there was no civil authority, no respect for law—but, instead, violence,, terror, threats and sedition.

The excitement which spread over the country by reason of these things now turned into a panic. Settlers fled in all directions. In the southern portion the frontier was pushed back eastward of the rivers. Here and there the remaining settlers gathered into temporary structures for shelter and defense. The panic spread to the northern frontier. Alarms occasioned by reports that the savages were about to cross the Allegheny river and break in on the northern frontier took possession of the people. St. Clair and the rest of the magistrates and agents of the Penns were busy night day, and going in all directions and urging the people to make a stand. Upon the individual guarantees and assurances of St. Clair, Col. Mackay, Devereux Smith and others, companies of rangers were formed whose pay was thus made certain. Block-houses and temporary stockades at various places, and stations for defence and for harborage of the ranging companies and people were established. These ranging companies were distributed for the most part along the line of the Forbes Road from Ligonier by way of Hannastown to the Allegheny river and Pittsburgh. In a letter to Governor Penn from Ligonier June 12th, 1774, (52) St. Clair says:

"In my last I had the honor to inform you, that in consequence of the Ranging Company which had been raised here, there was reason to hope the people would return to their Plantations, and pursue their Labour, and for some time, that is a few days, it had that effect, but an idle Report of Indians having been seen within, the Partys has drove them every one into some little Fort or other,—and many hundreds out of the Country altogether. This has obliged me to call in the Partys from where they were posted, and have stationed them, twenty men at Turtle Creek, twenty at the Bullock Pens, [seven miles east of Pittsburgh on the Forbes Road], thirty at Hannas Town, twenty at Proctor's, and twenty at Ligonier, as these places are now the Frontier toward the Allegheny, all that great Country between that Road and that River, being totally abandoned, except by a few who are associated with the People who murdered the Indian, and are shut up in a small Fort on Conymack, [Conemaugh], equally afraid of the Indians and the Officers of justice. (53.) The People in this Valley still make a stand, but yesterday they all moved into this place, and I perceive are much in doubt what to do. Nothing in my Power to prevent their leaving the Country, shall be omitted, but if they will go, I suppose I must go with the stream. It is the strangest Infatuation ever seized upon men, and if they go off now, as Harvest will soon be on, they must undoubtedly perish by Famine, for Spring crops there will be little or none."

The Indians in this uprising insisted from the first that their war was with the Virginians only. And in the end this was seen to be true, for their depredations were confined to the region in which the war broke out. St. Clair was about the only one who detected at an early date their attitude, and his sagacity has been the subject of comment at a very recent period. (54.) But there is no doubt that St. Clair's influence among the Indians on the north of the Ohio was very potent to this end.

St. Clair from Ligonier, June 16th, 1774, thus reports to Gov. Penn (55):

"‘Tis some satisfaction the Indians seem to discriminate betwixt us and those who attacked them, and their Revenge has fallen hitherto on that side of the Monongahela, which they consider as Virginia, but lest that should not continue, we are taking all possible care to prevent a heavy stroke falling on the few people who are left in this Country. Forts at different places so as to be more convenient, are now nearly completed, which gives an appearance of security for the Women and Children, and with the Ranging Partys, which have been drawn in to preserve the Communication, has in a great degree put a stop to the unreasonable panic that had seized them, but in all of them, there is a great scarcity of Ammunition, and several messengers have returned from below without being able to purchase. I am very anxious to know whether the ranging Companys are agreeable to your Honour or not, because both the Expense of continuing them will be too heavy for the subscribers, and that I am every day pressed to increase them. This I have positively refused to do, till I receive your Honour's instructions, and I well know how averse our Assemblys have formerly been to engage in the Defense of the Frontiers, and if they are still of the same disposition, the Circumstance of the White People, being the Aggressors, will afford them a topic to ring the Charges (changes) on and conceal their real sentiments."The last sentence in the foregoing extract reflects how the care and watchfulness of St. Clair, and the fear of results which were inevitable from the aggressions of the whites themselves, were manifested. After this letter had been written he added: "The day before yesterday I had a visit from Major [Edward] Ward. He informs me Mr. Croghan set for Williamsburg the day before, to represent the Distresses he says of the People of this Country. At the same time he informed Me that the Delawares had got notice of the Murder of Wipey and that Mr. Croghan had desired him to come to me on that occasion, that he advised that they should be spoke to and some small Present made to them as Condolence and 'to cover his Bones,' as they express it."

It will be seen that St. Clair expresses much Concern to the Governor "about the Murder of Wipey." There was no circumstance in that terrible year that was the cause of more apprehension to St. Clair or Croghan or Gov. Penn than of the killing of Wipey, a friendly Delaware Indian. For it is remarkable that while Dunmore's, or Cresaps' War, was traceable to the wanton killing of the friendly Indians at Captina and Yellow creek, that the entire Delaware tribe which had up to that time remained friendly to the whites, were on the eve of now breaking out on the northern frontier for a crime of the same nature—as heartless and cruel.

When a portion of the Delaware tribe, about the time of Pontiac's war, had passed from their towns on the Kittanning trail about Frankstown to their new hunting grounds westward of the Allegheny river, there was one of them, somewhat advanced in years, called Wipey who remained behind and built his cabin or lodge by a stream on the north of the Conemaugh in now Indiana county. The place was called by the whites Wipey's cabin. This lodging place of the old Indian was on or near the tract of land upon which George Findley, the first white man that settled north of the Conemaugh, located. This was before the title to the land had passed from the Indians to the Penns. When the land office was opened, Findley made application for a warrant for the tract which he had improved. This application is included among those in the list given by the Surveyor-General to J. Elder, Deputy-Surveyor to survey, and is literally as follows:

"Apl. 3, 1769. Application made by George Fendler (Findley), Near Wipsey's (Wipey's) Cabin Near Conemaugh River."

In old title papers the place is mentioned frequently, because it was well known and was a land mark on the trail from Ligonier to the old Kittanning Path. Wipey was at peace with all men, and from repeated evidences of his friendship, he had the reputation of being an inoffensive, harmless and hunter and fisher. He was, in short, regarded as a friend of the whites.

The circumstances of his unfortunate killing are related by St. Clair in a report to Gov. Penn from Ligonier May 29th, 1774. (56.)