Index:

Harper's Weekly Article

New York Herald Article* * * * * *

HARPER'S WEEKLY

New York, Saturday, June 6, 1857

Contributed by City Historian Peggy Haile McPhillips"Two Noble Women."

Annie M. Andrews

[From an Ambrotype by Brady.]We are fortunate enough to be enabled to present our readers with portraits of two of the noblest women of the present day—Miss Florence Nightingale and Miss Annie M. Andrews.

The former—be it said without disparagement to her eminent qualities and her paramount claims on the world of fame and on her countrymen for gratitude—enjoyed a remarkable advantage over our countrywoman in respect of the publicity of her noble deeds: she won her laurels in the blaze of day, when thousands of voices and pens were eager to proclaim her mission of mercy and her meed of fame; and if they were won at less personal risk than those of Miss Andrews, they involved, perhaps, a bolder character and less shrinking from the public gaze.

The two women differed in age, and somewhat in position. Miss Nightingale is a lady of some forty odd years of age; Miss Andrews was barely twenty when she embarked on her mission. Miss Nightingale is a lady of fortune and high social rank; when she announced her intention of proceeding to the East, a staff of officers offered her an escort, and a cohort of ladies of the best families of England solicited the privilege of being allowed to serve under her orders. Miss Andrews, though, we believe, a lady of some independent means, was living with an uncle at Syracuse when the terrible news from Norfolk roused her energy; she proceeded to the scene of her labors by railway alone and unnoticed.

But the contrast will be best discovered by a somewhat more detailed biography of Miss Andrews.

The father of Miss Andrews, a self-made man, a native of New York, realized a fortune by the practice of the medical profession in the South, and now resides on a plantation of his own in the vicinity of New Orleans. His daughter, the subject of this sketch, was not indebted to her parents for her education. At an early age she was placed with an aunt, to whom she owed a sound religious and moral training. While quite a child, her fondness for visiting the sick was remarked among her young companions. She seems to have been born a nurse. When the fever at Norfolk broke out, she was living with her uncle, Judge Hall, of Syracuse, New York; she instantly announced her desire to go and offer her services as nurse. The need of nurses was so pressing, it will be remembered, that the most enormous prices were paid for very sorry attendants; still, the danger was so obvious that Miss Andrew's relations were much opposed to the scheme. By much entreaty she prevailed on them to allow her to write to the Mayor of Norfolk, tendering her services; they consented—mainly from the persuasion that the Mayor would decline the offer.

He, like a prudent man, neither declined nor accepted. He stated the pressing want of nurses, and described the terrible suffering of the people, but gave no opinion on Miss Andrew's application.—His description of the destitution of the poor sufferers was enough for her; she stipulated that she was to pay her own expenses, and departed alone. For two days and nights she traveled alone by rail. On approaching Norfolk she met three Sisters of Charity, bent on the same errand as herself; in their company she reported herself to the Mayor, and received permission to serve as nurse. It was late in the evening when this formality was fulfilled; the Sisters of Charity, with professional experience, prudently retired for the night; Miss Andrews went directly to the hospital, and waited on the sick that night.

Previous to the outbreak of fever, Norfolk had no hospital; an old race-stand was temporarily converted into an infirmary and baptized the Julappi Hospital. It was a miserable building; through the roof the rain poured in bad weather; every moment Miss Andrews could steal from her duties as nurse was devoted to calking the seams in the building. Though courage sustained her frame under trials that were indeed terrible to bear, her duties involved inconveniences over which her feelings had no control. Her tender hands and feet, unused to work, suffered severely, and even, at times, stood in need of surgical assistance; and at last, finding the repeated annoyance too troublesome, she bathed both hands and feet daily in strong salt and water to harden them; succeeding, indeed, in her immediate aim, but at the cost of what every young lady prizes—her hands are wrinkled and discolored, like those of a much older person.

Those who have had experience of a yellow fever hospital can alone appreciate the danger and the discomfort of Miss Andrew's position. It has often been said that of all patients the most unpleasant to nurse are sufferers from gun-shot wounds; the effluvia from the wound impart a poisonous taint to the air. But experienced nurses aver that not only is the air around the bed of a person dying of yellow fever sickening to breathe, but is is absolutely loaded with a poison which is likely to be fatal to one of every two persons who inhale it. Our own history contains many instances of persons dying of yellow fever without a human being near them—so repulsive is their death-bed. Miss Andrews shrank from no trial of the kind. Many and many a poor sufferer, in his last delirious moments, was recalled to consciousness by feeling her cool hand on his fevered forehead, and by hearing gentle words of a future life uttered by her kind voice.

The patients, as we all know, far outnumbered the capacity of the hospital; the nurses were far too few. Miss Andrews was frequently in attendance at several death-beds at the same time. A visitor to Norfolk has preserved an account of one night during the height of the pestilence, when she was on duty in a private house. Two persons, one of whom was a physician, were dying of fever in the house. The physician was delirious; he ranted, and raved, and sang snatches of some old familiar tune. The other dying man had passed the crisis of the malady, and was quietly sinking into death. His companion's cries distracted him. Miss Andrews rose from his bedside, and approached the physician. She laid her small soft hand on his brow, and looked at him. The cool pressure roused him; he looked up, started at seeing this fair girl beside him, and muttered—"Who is this?" Kind womanly words of sympathy and consolation taught him that the intruder was a friend; he was subdued and quiet. His nurse hastened to return to the dying man in the adjacent room. His agony had come. Her task was now to support the dying head during the minutes which life had yet to endure. Midnight was long past; she was alone; the physician, relapsing into delirium, had begun to scream and to sing again. What nerve that young girl must have had! A brief space released her from her care of one patient; he died with his head resting on her arm. Then she hastened to the poor physician. At the first sound of her gentle voice his paroxysm ended; calm was restored to his wandering spirit; he was enabled to listen consciously to the pious exhortation of his last friend. He had a wife—but she was far away; it was Miss Andrews who, in that dreadful hour, stood in stead to him of mother, sister, and wife, and soothed the moments which preceded his final dissolution. Gray morning dawned as he died. What a night!

Even death did not limit the cares which her self-imposed mission devolved upon Miss Andrews. When patients died of yellow fever, it was almost impossible to find persons to lay them out for burial; this also fell to her lot; and when the number of corpses made it necessary for her to hire assistance, she paid for the service of a negro out of her own funds.

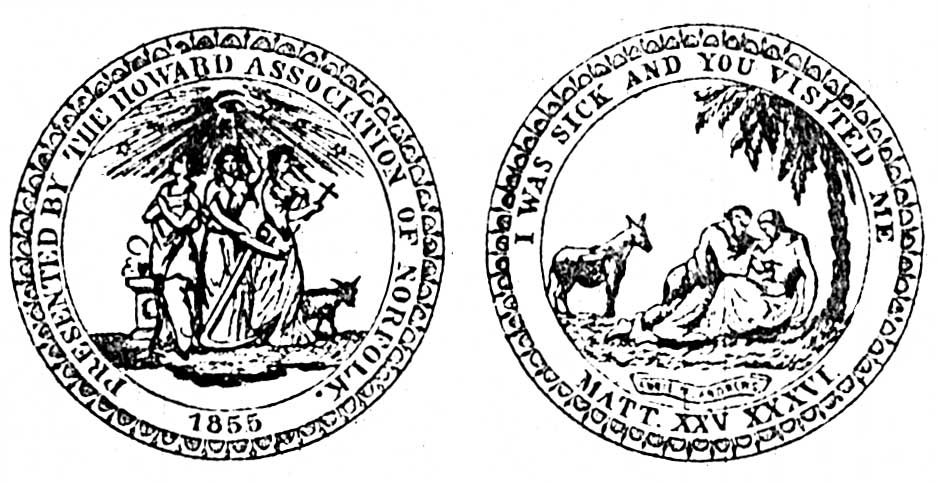

Medal presented to Miss Andrews by the

Howard Association of Norfolk.It only remains to say that the Howard Association of Norfolk, grateful as well for the eminent services of Miss Andrews as for the noble example she set, have presented her with the gold medal usually awarded to physicians. Impressions were kindly furnished us by the officers of the Association; and we engrave them above.

When Miss Nightingale's noble career as a nurse was ended, the people and army of England took counsel what they might do to testify their admiration and love for the woman who had proved herself the heroine of the war. They proposed all kinds of testimonials, which were unhesitatingly declined by the lady. A negotiation between her and the public was then set on foot; it resulted in a decision to build and endow a hospital in memory of her, and bearing her name. The subscriptions are just now closing; it is understood that they have reached a figure which will enable the trustees to fulfill the intentions of the public in a manner worthy of Miss Nightingale and of her glorious services. We have not heard that it is proposed to erect a hospital in memory of Miss Andrews; but we should think that very many of the citizens of Norfolk must be anxious to testify their sense of their obligations to her; and if no more was done than the mere erecting of her statue in a public place in Norfolk, we should imagine that the act would be a source of high gratification to the citizens of the town and the people of the State.

* * * * * *

NEW YORK HERALD

Sunday, September 20, 1857

Contributed by City Historian Peggy Haile McPhillips"The Heroes of the Pestilence; or, Glimpses of Norfolk As It Is."

By Annie M. Andrews.A few days since we had the pleasure of announcing the completion of a work by Miss Annie M. Andrews, the lady who distinguished herself by her generous self-devotion during the the height of the yellow fever visitation at Norfolk. No purpose of self illustration is contemplated by Miss Andrews in this, her first, literary effort. With the philanthropy and disinterestedness which have always marked her conduct, she hopes to serve a double object by it—that of commemorating the heroic labors of those who were associated with her in her trying labors, and of relieving from its proceeds the necessities of the families who were bereaved of their natural protectors by the pestilence. We have been honored with the proof sheets of the introductory chapter of this interesting work, and are satisfied that our readers will derive as much gratification from its perusal as we have done.

Iniatory Chapter

It is, perhaps, expected that I should preface this work by noting some of the motives which induced me to go to Norfolk in the pestilence, some of the details of my three months sojourn there, and, it may be, some of my own reflections respecting that awful visitation, in progress and in result.

The whimsical, eccentric voice of popular praise, by the press and by word of mouth, have not left me, at this late day, the necessity of introducing myself to the public, whom, without any affectation of modesty, and for good reasons known to myself, I am anxious should read my book.

Of the impelling power which decided me upon making my pilgrimage to the city of the pestilence, I have only to say that God sometimes puts it into the hearts of his feeblest ministers to attempt, and in their hands to render light such works as man, frail man, looks at and wonders. From a child it has been my delight to attend upon the sick, even when I could render no more service than with my hands to wield the fan or fly brush beside the bed of some invalid. Each of us in life has his or her own peculiar proclivity to some one calling more than all other. This was mine.

It has been assumed, then, from what is herein already written, that I obeyed a natural instinct in going to Norfolk in the fever; neither am I susceptible of disease. Independently of these, I am unprepared to say what response the imploring cry for help which went up from the doomed city in 1855 would have excited in my breast.

Through the medium of the omnipotent press what a wail sounded upon my ear!—a chorus of crushed hearts.

This way—that—amid sounds of festal music and merry laughter, that lament rose above it all.

Go her, go there amid gay scenes—the pageantry of earth—Oh! there could not come between me and that dark vision, which the mind seemed to treasure with such morbid cares—the city of the dead and dying—the dark-winged Spirit of the pestilence brooding over the spot, breathing poison upon loving and loved, sundering heart ties and the soul's dearest affections with hand as ruthless as one would scatter flowers to the summer winds.

The mail from the South came again—not better, but worse, the tidings it brought. No longer could I endure the harrowing picture, and so resolved to write to the Mayor of Norfolk, proffering my poor service as a nurse for the afflicted of his sorely stricken city. Friends interposed with their kind persuasions. They bade me consider my undertaking— its possible hazardous consequences. All these had been contemplated, too, the position of a woman who alone goes forth to a work, however hallowed, with the eye of publicity resting upon her course. No prudential suggestions could then, or can now, take me unawares—all have been considered, and could I have then foreseen every attendant circumstance which has since developed itself in connection with that of which I am speaking, I should no more now than then shrink from the work.

Mayor Woodis did not reply to my letter volunteering my services as nurse because, as he afterwards told me, he shrank from the responsibility of advising me to risk my life there, and also from rejecting my service proffered thos so sorely in need of help.

I would not wait for a letter; left Syracuse, the house of my uncle, Judge Hall, en route for Norfolk.

Three Sisters of Charity left Baltimore in the same boat with me; there had been no volunteers then—we were the first. Some of the Sisters, with myself, set out in a hack, upon our arrival in Norfolk, to find the Mayor and report ourselves ready for duty. We overtook that good man not many squares from the landing; he was pointed out to us by the hackman, who beckoned to him and then drove up. His noble face, frank manner and cordial shake of the hand, remain with me to this day, though the time is two years passed. Corruption has enfolded that manly form, and on that eye, that hand, the worm has made his meal.

On that morning the Mayor took me in a carriage out to Julappi Hospital, the destined sphere of my labors, or rather I had designed it as such: yet at the instance of my friend, the kind and noble Upshur, I was induced to go to the city on sundry occasions to lend a helping where required. On the morning in which I reached Norfolk by the Baltimore boat, there seemed a peculiar state of affairs prevailing, and yet not peculiar, although at each successive occurrence of a like season, wherever it be, we will insist upon applying this term—I allude to the apparent carelessness, nay, wantonness of manner, characterizing the community where a fearful plague rages. Truly, I cannot think such visitations soften the heart. God has in this work his own wise designs, doubtless, and they shall eventuate in goal according to his purpose; but surely man's heart is hardened that they shall not effect like other afflictive dispensations.

"What news?" inquired one from on board the steamer Georgia, on which we came passengers. "Such an one is dead;" "Dr. ___ has put such an one through," "and we put away so and so, &c., last night;" and then came a catalogue, rattled off like random shots, of individuals who had fallen victims to the unerring archer. In such light tones and manner spake the voices on shore, most of them. Many had lost parents, children, wives, brothers, sisters, it was all one; they were stunned, not afflicted. What did it mean? Could I ever arrive at such a degree of callousness: "Is thy servant a dog that he should do this thing?" How little we know ourselves! Death grew a thing of such every day import that (Heaven forgive me and all of us!) we grew to speak and think as lightly as the rest.

We became regularly installed at Julappi, about four miles from the city. The Sisters were placed in charge. Dr. Wilson, the physician to the hospital, took up quarters about half a mile off; and Major Woodis, Ferguson, the illustrious and heroic President of the Howard Association, Dr. Upshur, and sometimes another consulting physician, were our daily visitors.

What more salubrious spot, far as location was concerned, could have been selected for the sick and suffering of the pestilence stricken?

The broad expanse of the deep blue bay on which the summer sunshine fell like molten gold, the surrounding woods and vast fields, the broad armed giant trees which cast their shade around, and the fresh, delicious breezes, ever awake there, these spake all of health and enjoyment. But, oh! the sickening contrast of all these natural delights with the other sights and sounds within and about Julappi Hospital! Methinks I see the ever active Woodis bringing up to that shore another doomed company in every stage of that fearful disease. The first chill, may be, has just passed off; his appearance, or her's, may not as yet present a threatening aspect; another attacked in the same manner and time lies prostrated now, so that we doubt if medical aid will avail aught in such a case; another lies covered from head to feet with the vomito; there an infant is striving to suck the life stream from the fount which death has frozen forever; here a little pale girl drives away with the shattered straw hat the flies from the face of a sun burnt sailor-looking man. He does not know that he minds them not, aye will never mind them again; he died as many do, on the passage down from town.

Curses, loud and deep, come from yonder couch within. Miserable creatures are they, the set they brought in last night. This patient's only cry is for "liquor, more liquor." And now oaths—frantic, terrifying.

"Sister Christine and Sister Lucia" she says, (some of them always called me thus, owing to a misprint of my Christian name when I first arrived in Norfolk) "are both drunk." She will die cursing. Heaven have mercy on her soul.

A man lies in yonder outhouse, ill of delirium tremens. What hideous yells to assail the ears of parting spirits. Be thy heavenward-bound celestial music sweeter. Should— should— (awful thought!) the regions of misery be theirs, scarce more demoniac sounds shall issue thence than those we hear from yonder quarter.

It is night—still, silent night—and from the direction of yon thicket of pines by the shore, issue sounds the most doleful—mournful wailing, sobbing, sighing shrieking. There is no living being there that we are aware of; we have no one to send and see; Sister Christine and I are watching by a dying patient, and it is horrible to hear such sounds at such a time. I am not nervous, but truly this staggers me. If at such a crisis one would try this to frighten us, to what might they not eventually resort. There was and had hitherto been no male protector to the establishment. Sister resolved it must be so no longer—tomorrow she would go speak to the Mayor about it.

It was a miserable house that hospital, or rather, it was a miserable set of houses, for there were two or three smaller tenements beside the main building, appropriated to the various patients who were brought in, and one of them constituted the sleeping apartment wherein the Sisters and I were expected to take our uncertain rest.

In rainy weather, of which it will be well remembered in Norfolk and the vicinity, that there was a superabundance, we were busily employed, in addition to our other duties, in stopping the cracks and wide seams in the walls, which admitted the water in sluices.

Of course no other labor could be obtained than what this casualty bestowed, and yet this Julappi Hospital, with all its disadvantages of this kind, was the saving strength by which many were preserved to life. Of course numbers of those who were installed here left much more miserable tenements in the lanes and alleys of the city.

Those upon whom disease had not too nearly accomplished its work, had here surely a safer chance for life, amid the surrounding influences of a pure atmosphere, and by aid of good nursing and proper nourishment.

The idea of the "infected district" of the city, exploded early in the day. Whenever previously the yellow fever had visited Norfolk, it had never progressed beyond a certain given stand point toward the northern section of the city. It was in consideration of this fact, that many of the citizens—my kind, gratefully remembered friend, Dr. Upshur, among the number, removed from their residences, down town, toward Selden's Point, Upper Granby street.

On the 7th of August, I think the first case occurred, followed speedily by many others, proving that the disease was confined to no locality.

Some of the patients where I was attending had been fugitives from Barry's row—consisting mostly of Irish laborers—to other portions of the city, and had finally resorted here. Barry's row it is well known to those familiar with the history of the pestilence, was the first place in Norfolk attacked by the disease. This is readily enough accounted for, independently if the reputed want of neatness characterizing the habits of the persons occupying these dwellings, when we reflect that numbers of their occupants were workmen at the Gosport Navy Yard, contiguous to which the ill fated steamer Ben Franklin, the messenger of so much woe to the two cities of Norfolk and Portsmouth, then lay. Besides, there was a nightly flight of refugees from Gosport to those tenements, both sick and well, with their household goods, clothing, &c, fleeing from the face of the destroyer to what was then considered a healthy section. All this was going on from the middle to the last week in July. The death of Mr. Robert W. Warren, who was clerk for Page & Allen, at their shipyard in Portsmouth, but resided in Norfolk, seemed to give the first actual alarm to the citizens. He was attacked on Wednesday, the 26th of July, and died on the following Saturday night. On the succeeding Monday Dr. Upshur took the responsibility of making known the existence of the yellow fever in the city of Norfolk. He had feared that such was the nature of the disease which, from about the 16th of June, had been developing itself among certain occupants of Barry's row. I think that all the cases of the disease had, thus far, come under his practice. Many as has been said, were already in a state of great excitement, while others called Dr. Upshur an alarmist, and designated the disease the "Upshur fever;" others, again blamed him for not having made known the facts of the case at an earlier period, that provision might have been made for removing the fever patients beyond the city limits, and for adopting such other sanitary measures as would have prevented the dissemination of contagion. Business men affirmed that he had injured, unnecessarily, the trade of the city to an amount that thousands would not cover. Reflecting upon these circumstances, I deduce only one more additional evidence of the worthlessness of man's praise or censure when weighed against the reward of a good conscience.

Mayor Woodis removed the sick from Barry's Row, and caused the streets leading to the "infected district" to be firmly barricaded, so that no one should come in future contact with the contagion there. A crowd of low persons came while the work was in progress, and defied the Mayor to cut off their principal passway thus: "It shall not go up," said they. "It shall go up," replied the fearless Woodis, "and what is more, shall remain up. I'll watch here night by night but I'll maintain my point."

Dr. Upshur, with his characteristic playfulness of speech, denominated the barricade "Woodis' board of health."

At our hospital Sister Susannah performed the cooking and attended to the domestic arrangements of every sort, while Sister Christine and Sister Mary Levis, with myself, undertook the nursing. I suppose the number of patients we had was about sixty to seventy a day. By these we watched daily, and alternated the periods of night rest. We lost the most, between twenty and thirty, in a day. Methinks the moonlight never seemed to shine so brightly as on that field of death. Night after night, when starting from the hospital to the house in the yard where I was to seek some repose, I have loitered in the gallery to watch the calm stars looking so peacefully down upon the scene, and the silver flood of moonbeams which seemed to etherealize all below. Calm, beautiful aspect of nature! Where was the omnipotent death spirit, of form invisible, but whose woeful work was everywhere around! How upon scenes like this could he intrude his poisoned presence? Perhaps in contemplation like this the mournful wail of a sufferer whose bedside I had just left would proclaim the rapid approach of the monster—the last final struggle between the "last enemy" and his victim.

I had been about three weeks at the hospital when Major Woodis requested me to go with him and nurse a family in the city who were in sad want of attendance; so, through the broiling sun of a summer noonday we traveled up to town. I was left waiting for some time; finally an elderly lady, a temporary sojourner in the family, came in and commenced telling how that Mrs. ___ was not prepared to receive strangers, &c. I considered the topic altogether irrelevant to my professed errand, and could not determine the gist of it. I had not come there to be entertained. Finally it appeared that the family did not, from some secret cause, desire my services. The wherefore of the case presented themselves subsequently. Mr. Woodis and I meanwhile had taken our warm tramp back to Julappi. The family of ___ were staunch Know Nothings, and I was credibly informed in effect that they believed me a sort or moral egress, in other words, a Papist disguised, designed to devour with voracious appetite the purely Protestant morals so zealously inculcated in the children of the family, drink dry the stream of inimical feeling to Popery, and finally leave the little innocents with so subdued an amount of bigotry as to enable them, at the close of our relation as nurse and patient, guilelessly to declare that truly some good thing could come out of Nazareth.

The circumstance of my being the first Protestant volunteer induced many to class me with the Catholics. Was it pleasant, down at the hospital, to scour the black vomit from the floor, the bed clothing, the patients themselves? To shroud the dead bodies of large framed, unwieldy women? To discharge service of any and every kind which presented itself with need of performance?

Yes, in one sense it was; such pleasure as I sought came with the deeds performed. Some soul, perhaps, had breathed my name in blessings as it went to its upper home; conscience had gained a victory over human nature's inherent fear and weakness.

Of the noble band of Sisters of Charity who hold themselves ever in readiness for work such as this, and of those especially who attended the hospitals in Norfolk and Portsmouth during the prevalence of the fearful epidemic, more especially of these who in my sight each day performed such deeds as only true, fervent faith could inspire, I would write volumes—true admiration for the heroic, the beautiful attributes of genuine exalted Christianity guiding my pen the while. But such a work would be only a succession of such deeds, and my own enraptured comments. For the edification of the general reader I have made an attempt to procure some points in the respective private histories of those with whom I served at Julappi, but without success.

A friend of mine in Norfolk called on Sister Bennard, principal of the Sisters of Charity House, in that city, to solicit such incidents, expecting them as she might possibly be possessed of, but she wrote me, "My attempts to collect such incidents as would be useful to you have proven fruitless." Sister Bennard, in her peculiar sweet voice and manner, informed me, "that their, for the most part, migratory mode of life prevented any prolonged or intimate association between the different members of the sisterhood, except in a professional way. I know," said the Sister, "that they each and all performed their work, here and elsewhere, with great fervor and zeal; besides this, we know nothing of them. Tell Miss Andrews," she added, "that I return her thanks for her kind desire to give the Sisters of Charity a place in her book, but that if our names be but written in the Lamb's Book of Life, we ask no more—this one great boon covers all."

The Howard Association, by the almost superhuman aid tendered by the cities of Baltimore, New York, Philadelphia, Richmond and the Southern cities, was enabled to supply our necessities most bountifully. Nothing we could name as requisite for our sick but was furnished immediately, of the best kind and in the best manner; nothing we could desire for our own comfort in the way of food and refreshment, but what was pressed upon us. We have much in this way for which to return thanks to that body who organized themselves for their city's service.

* * * * * *

I revert now to the time when there were no coffins to be had, when, under two day's summer sun the corpse of a man, who died among us, lay festering on the gallery leading out from our long dormitory.

The coffins came finally; on a bright Sabbath morning, a large wagon drove up freighted with these receptacles for the dead. Sister Christine and I lifted the corpse into one of those, then lowered it over the sides of the gallery to the men who awaited it below. The other coffins were piled in a fearful looking heap at the end of the house to await their season of availability, destined not long to be deferred. It was a woeful state of things in the city when coffins, boxes, all gave out, and finally when the long-to-be-remembered Baltimorean sent down the steamer with its fearful freight, Oh there was rushing, and seizing, and bearing off, that friends dearest and best might be hurried away forever from the sight of those whom they loved and who loved them most.

To the scenes which were transpiring in the city I was frequently an eyewitness, having gone at the instance of Dr. Upshur, (to whom after poor Woodis' death, I looked for counsel) to nurse, there in the families of some whom he regarded as especial friends. Miss S. F., whom I nursed under his direction, by her sweet, grateful manner and Christian deportment, endeared me much to her. All her nourishment was prepared by my own hands, and she was always ready to praise every service which I rendered—different in this respect from many upon whom I tended—that she seemed over fearful of giving trouble, or of requiring too much at my hands. She commended me in kindest terms to her family just before her death.

From hence Dr. Upshur took me to the family of a cherished friend, Rev. A. S. S., [Aristides S. Smith] whose excellent wife had lately fallen a victim to the prevailing epidemic, and whose young son and interesting little daughter were destined, despite physicians' skill and nurses' care, to follow her upon that same trackless journey whither she had gone.

In East Bute, and interesting family—a widow C. and her two daughters—were placed in my charge. One of the Misses C. died first, then the mother, lastly the other Miss C.

It would be distressing to describe and to read all the various scenes which came under my observation during my mission in the city.

The Howard Association, unless they had been omnipresent and omnipotent, could not have provided for the contingencies of each separate individual; neither could private charity penetrate, save by chance, into every abode where there were need and suffering.

It chanced that the present writer, while on an errand of business in Bute street, chanced to enter the dwelling of Mrs. ___. The woman was almost starving for nourishment, besides being ill. She had no one to send to the office, or to any place where supplies were kept. There was a provision depot open at the Lancasterian school house on Holt street, and Mr. William F. Tyler was placed in charge. I took a hack, which, more by good fortune than good management, I succeeded in procuring, made my desires known to Mr. Tyler, and was furnished with such articles as I needed—a live chicken, crackers, bread, rice, sugar, &c.—when I set off again.

Almost every mail that came during my mission to Norfolk brought me bundles of papers from the different newspaper offices throughout the country—editorial notices and extracts, marked with the pen—as in more leisure days I discovered—for my especial perusal; and letter after letter, with strange signatures, commendatory of my course in coming to Norfolk. The capricious voice of popular praise thus gave vent to present excitement. Of course the next actor in the next drama should transfer my applause to himself. Such is my estimate of the public voice of commendation, though I gladly add that as concerns individuals there are some whose friendship and affection I can boast, to which only this step could have led me—those weak hands and a feeble frame failed to execute all my heart designed—some who love me for what I wished to perform for the stricken city.

I cannot permit myself to close these desultory details without especial mention of some whose names present themselves to my mind, thus:—

Visitors, Physicians and others.

Dr. S. D. Campbell of New Orleans. Dr. E. D. Fenner, New Orleans. Capt. Thomas J. Joy, New Orleans. Dr. J. T. Hargrove, Richmond. Henry Myers, Richmond. Dr. H. J. Revenel, Charleston. Dr. W. Huger, Charleston. Dr. J. B. Read, Savannah. Dr. MacFarland, Savannah. Judge Olin, Augusta, Ga. Dr. R. M. Miller, Mobile. Dr. Wm. H. Freeman, Philadelphia. Dr. G. S. West, New York.

I would particularly mention among the MEMBERS OF THE HOWARD ASSOCIATION OF NORFOLK Augustus B. Cooke, President, successor to Ferguson. Solomon Cherry, Secretary. R. M. Balls. William F. Tyler. George Drummond.

Clergymen.

Rev. Aristides S. Smith, Episcopal Church. Rev. Father O'Keefe, St. Patrick's Catholic Church. Rev. Lewis Walke, Episcopal church. Rev. D. P. Wills, Methodist Church.

The Resident Physicians of Norfolk.

These performed faithful and efficient service; among them I reckon the names of— Dr. William Selden, Dr. Robert B. Tunstall, Dr. William J. Moore, Dr. E. D. Granier, Dr. D. M. Wright, Dr. W. M. Wilson.

All the names upon the above written lists I reckon as those of my living heroes, they having almost miraculously survived the fell pestilence whose power they almost tempted in their exertions to interpose betwixt the destroyer and his victims. I name them as those whose course I almost individually, in their respective capacities marked and admired as praiseworthy in the extreme, and to more than one of them I can scarce refrain from ascribing praise and gratitude due for the marked personal kindness voluntarily bestowed upon the stranger girl adjourning among them.

My initiatory chapter draws nears it close. I am conscious that it and the records which it is designed to preface are alike incomplete for the nature of the work which I have undertaken, with my imperfect facilities for carrying out the same, have all combined in a general tendency to make it but a fragmentary production.

When my labors ceased at Julappi Hospital, and when I bade adieu to Norfolk city, I asked myself the question (not with regard to the present purpose, of which I had then no thought), what from that panorama of death I had brought away with me? From the shifting scenes, all painted in varied lines of darkness, here and there stood out one more prominent then the rest; as these have flitted across my sometime bewildered brain, and left their impress, I have endeavored to transfer them here; yet pen and ink and feeble hand can but fail to give adequate expression to scenes stamped upon that page of time known as fifty-five—traced with the sceptre of death, and dipped in the heart-blood of heroes.

There are many, I doubt not, whose names even have been missed here, whose hero work is entered among the debits and credits of the eternal reckoning book; they have their reward where praise of man is but feeble commendation; but of such and to those who loved and survived them, I have only to say that such omission upon my part has been altogether undesigned—that I have been at much pains to commemorate such names as have heretofore been passed over in silence; my desire to effect this has been attended with but partial success, yet I cannot seem unmindful of the fact that there were these who went down to hero graves "unwept, unhonored and unsung" in those fearful days and in subsequent times, whose names in that great day of days shall make earth's children to wonder as those to whom shall be ascribed the honor due them who obeyed the behest "Bear ye one another's burdens."

Of many whose names stand foremost among the lights whose rays of goodness illumined that night time, I have been constrained to merely mention only [a few]. They form a prominent portion of the history of that period, but I have not been enabled to trace them in their home relations nor in any period prior to that in which they are here presented, many of them only in a general way.

Whatever facilities have been afforded me I have endeavored to use to the best advantage. When I reflect on some whose names are written here; think how themselves traced it in their own hearts' blood upon the pages of time and memory; think what a feeble transcript is mine—there works a disheartening influence within me; yet with the recollection of my design in laying this book before the public, I grow regardless of those master hands who may hereafter, and I hope will, essay to paint the Heroes of the Pestilence, and for mine only say:—"What is writ is writ—would it were worthier."

THE END.