Daniel and Mary Bell and the Struggle for Freedom

by John G. M. Sharp

Daniel Bell (1804-1877) a Washington Navy Yard blacksmith and his wife Mary (1802-after 1883) sued for their freedom and in a decade’s long battle tried to use the courts to uphold their manumission and that of their children.1 When the legal system failed them, they turned to the Underground Railroad and in April 1848 the Bell’s helped plan one of the largest and most daring nonviolent slave escapes of the antebellum era.2

1 Thomas III, William G., A Question of Freedom: The Families Who Challenged Slavery from the Nation’s Founding to the Civil War (Yale University Press, New Haven, 2020), 240.

2 Pacheco, Josephine E. The Pearl, A Failed Slave Escape on the Potomac (University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill, 2005), 113. Mary Kay Ricks Escape on the Pearl: The Heroic Bid For Freedom on the Underground Railroad (Harper-Collins: New York 2007), 37. John G. Sharp Daniel Bell Blacksmith Striker circa 1804-1877 Genealogy Trails 2008 http://genealogytrails.com/washdc/biographies/bio4.html Chris Myers Ash & George Dereck Musgrove Chocolate City: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation's Capital (University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill 2017), 90. Kenneth J. Winkle Lincoln's Citadel: The Civil War in Washington D.C. (WW Norton: New York 2014), 30.

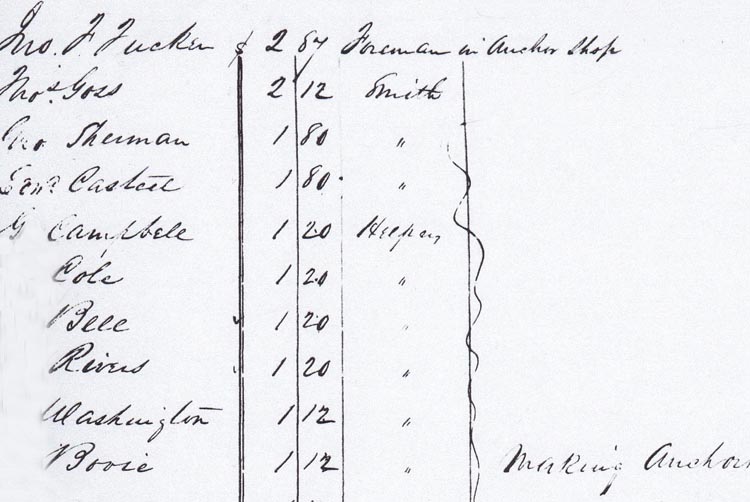

Early Life: Daniel Bell was born circa 1804 in Prince Georges County, Maryland, on land belonging to the slaveholding Greenfield family who found it profitable to rent him out to the Washington Navy Yard.3 At the Navy Yard, Bell worked for over twenty years in the Anchor shop, where heavy iron was cast, as a blacksmith striker. He wielded a heavy hammer to fashion metal anchor chain, anchors and other nautical items.4, 5

3 Thomas, Ibid

4 Pacheco, 48

5 Green Mountain Freeman (Montpelier, Vermont) 28 September 1848, p. 1.

The Washington Navy Yard Blacksmith and Anchor Shop: One early visitor to the navy yard blacksmith shop was English author, Lady Emmeline Stuart Wortley. Wortley, writing in the late 1840‘s, marked the prevalence of slave labor at navy yard: “We saw a sadder sight after that - a large number of slaves who seemed to be forging their own chains, but they were making chains, anchors, &c., for the United States Navy.”6

6 Wortley, Emmeline Stuart, Travels in the United States, etc., during 1849 and 1850 (New York: Harper and Brothers), 1851, p. 85.

During the first three decades of the ninetieth century within the District of Columbia and the Navy Yard, there is ample evidence of growing black use and awareness of the legal system. Due to their proximity to an expanding population of free blacks and a few sympathetic whites, some enslaved workers at Washington Navy Yard were able to utilize the constrained legal system of the District of Columbia to contest their enslaved status.7 In 1809 navy blacksmith helper David “Davy” Davis, through his attorney, filed a petition for freedom. As blacks like Davis challenged their enslavement, word spread at the navy yard that there were opportunities, albeit narrow, to take a freedom petition case into the District Courts. Among the enslaved shipyard workers who made this heroic effort, the long and protracted case Joe Thompson vs Walter Clark 1815 is a benchmark.8 Thompson, a blacksmith striker, through his attorney Francis Scott Key, fought and won a lengthy battle for freedom for himself and his family.9 At the Anchor Shop Daniel Bell worked with Thompson and most likely spoke with him about his heroic legal struggle.

7 Sharp, John G. African Americans in Slavery and Freedom on the Washington Navy Yard 1799 -1865, p. 1.

8 Joe Thompson v Walter Clarke , Petition for Freedom 31 May 1815 http://earlywashingtondc.org/doc/oscys.case.0036.001

9 Sharp, John G.M. The Washington Navy Yard Strike and "Snow Riot" of 1835http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/washingtonsy.html accessed 29 December 2020

During these years of unrequited toil, his boss was master blacksmith John Davis of Able. John Davis of Abel was a slaveholder, yet in 1848 he other white workers, with no sense of irony, toasted the new republics of South America and declared they “firmly be established on the basis of equal rights and equal liberty."10 Davis, himself as a young man, had nearly been impressed into the British Navy. This bifurcated mind set, praising freedom abroad, while holding blacks enslaved was common. Presidents Jefferson and Madison shared similar beliefs. Davis benefited directly from slaveholding and bluntly made the case for the employment of slave labor at the Navy Yard: “We found by long experience that Blacks have made the best Strikers in the execution of heavy work & are easily subjected to the Discipline of the Shop - & less able to leave us on any change of wages.”11

10 13 April 1848 National Intelligencer, 3 “Celebration in Honor of the Late Events in Europe.”

11 John Davis of Abel to Tingey, dated 15 March 1817, RG 45/M125, NARA.

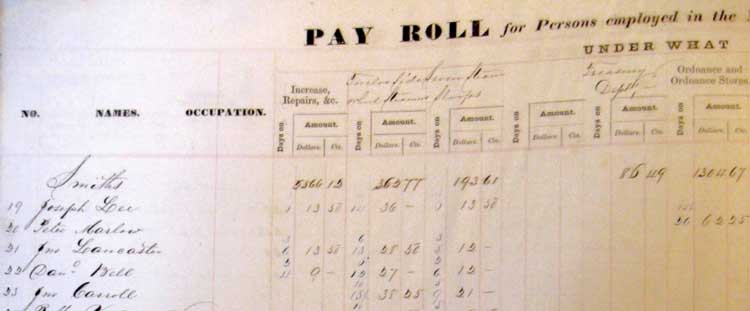

Washington Navy Yard payroll

January 1848, employee, no. 22 Daniel Bell, blacksmithAt the shipyard, life for the enslaved was precarious. Discipline at the shipyard for the enslaved ran the gamut from verbal reprimands, threats to inform the slaveholder of an infraction, strikes with a boatswain's starter (a piece of rope, dipped in tar), and whippings administered with a cat of nine tails (a multi-tailed whip, "the Cat" was made up of nine knotted thongs of cotton cord about 2½ feet or 76 cm long), designed to lacerate the skin and cause intense pain and lastly removal from the Navy Yard and return to the slaveholder.

All the enslaved were legal property, thus local slaveholders normally administered discipline themselves. Many of the shipyard naval officers and master mechanics were slaveholders. In 1810 Benjamin Henry Latrobe, engineer and architect, wrote to James Smallman, inventor and installer of the yard’s new steam engine:

Ben. King is forging the Crank. He has thought proper to alter his opinion and is making it the most tremendous lump of Iron, the Necks 4 inches in diameter, the squares 5 inches. He now thinks it too weak. He has been swearing and whipping his black Strikers at a terrible rate these two days past ...12

12 Benjamin Latrobe to James Smallman, dated October 5, 1810, Benjamin H. Latrobe Papers of Benjamin Henry Latrobe. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1984-1988, Volume II, p. 911.

While Latrobe had come to hold King in low regard, there is no reason to think he spoke metaphorically. Michael Shiner, writing a few years later, recounted how infractions were handled. Speaking back to an officer, overstaying leave, fighting or getting drunk could result in “a starting,” that is being hit with the boatswain's starter. For more serious offenses, blacks were whipped with the cat of nine tails. Shiner recollected the day that Commodore Tingey‘s footman was taken to the Rigging Loft for punishment.

At the same time they wher a lad comerder tinsay foot man had been cuting some of his shines at the house on the 4 and they taking him down to the rigin loft that it give him a starting and they wher going to give me starting two.13

13 Shiner, Michael, The Diary of Michael Shiner Relating to the History of the Washington Navy Yard 1813-1869, 1828, p.27, Sharp, John G, editor, Navy History and Heritage Command, 2015 https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/d/diary-of-michael-shiner.html accessed 30 December 2020

Payday was not for the enslaved at the Navy Yard's Blacksmith and Anchor shop. Early muster rolls reflect a signature block beside the employee’s name. Free employees, white and black, signed or made their X as acknowledgement of receipt. Apprentices and enslaved workers wages were signed for either by the apprentice’s master mechanic, the slaveholder or the slaveholder’s agent. The 1811 Muster Roll is the best surviving of such documents. Master blacksmith Benjamin King, for example, signed for his slave apprentice Tom Macom. Likewise master plumber John Davis of Abel signed for his two enslaved workers, John Smoot and John Legree.14

14 Sharp, John G. Washington Navy Yard Payroll for 1811, http://genealogytrails.com/washdc/wny1811.html

In the 1830’s Michael Shiner, an enslaved painter, and his wife Phillis began legal actions to secure the freedom of Phillis and the couple’s three children, Phillis Shiner v. Levi Pumphrey 1833.15 In 1836 they again took action, Michael Shinor [Shiner] v. Ann Howard and William E. Howard 1836, to secure Michael Shiner’s promised testamentary manumission.16

15 Petition for Freedom Phillis Shiner V Levi Pumphrey.

16 William G .Thomas III, Kaci Nash, Laura Weakly, Karin Dalziel and Jessica Dussault. O Say Can You See: Early Washington, D.C., Law & Family, University of Nebraska - Lincoln. http://earlywashingtondc.org

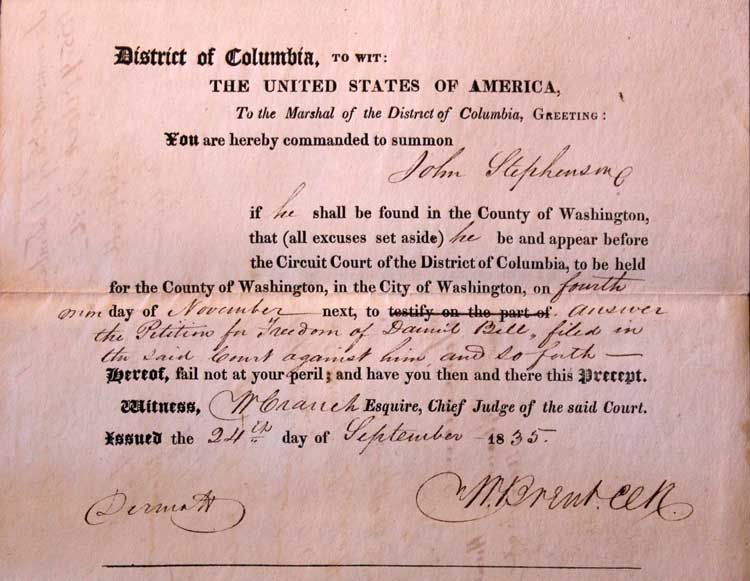

The District Court: In September 1835 Daniel Bell filed a Petition for Freedom, Bell vs. Stephenson 1835, with the District of Columbia Circuit Court. Bell's Petition for Freedom was dismissed by the court on 24 October 1835.17, 18

17 Ibid, http://earlywashingtondc.org/doc/oscys.case 0175.001

18 National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 21, Entry 6, Box 539, Folder 381

Daniel Bell's desire to win freedom for his family was further complicated by the fact that his wife and children were the property of yet another slaveholder, Robert Armistead, navy yard master ship caulker. On 14 September 1835, shortly before Armistead’s death, Bell persuaded Armistead to make a testamentary manumission for his wife Mary and the couple’s six children, which was duly registered with the District government. Bell’s wife Mary was to be freed at Armistead’s death while each of the Bell children were to be set free only after serving various stipulations of term servitude, e.g., Andrew Bell, sixteen in 1835, was to be set free at age forty.19 Though Bell as a free man was able to earn a decent wage of $1.20 a day, his troubles however were far from over.20 In reprisal for Bell’s efforts on behalf of his family, it is probable that the slaveholding Greenfield family, at the urging of Susannah Armistead, had Bell seized at the Navy Yard.21 He was then hauled off to a slave pen located on 7th Street SE and Maryland Avenue, the notorious “Yellow House” operated by the infamous William H. Williams where he was placed for sale.22, 23, 24 Fortunately some of Daniel Bell’s friends were alerted and helped arrange for Bell to be purchased by a naval officer who agreed to purchase Bell and let him eventually attain his freedom through regular payments.25

National Intelligencer, Washington, DC

I wish to purchase a number of servants of both

sexes for which I will pay the highest market

price. Persons wishing to sell will do well to call

at my residence near the National Hotel. Letters

addressed to me through the Post Office will

receive the earliest attention.

William H. Williams, Washington

10 February 1836, p. 3.19 NARA, Record Group 21, Entry 115, O.S. Case file, 1832, Robert Armistead. RG 21.

20 Ricks, 130.

21 Thomas, 251.

22 Ricks, 57.

23 Forett, Jeff, The Williams Gang: A Notorious Slave Dealer and his Cargo of Black Convicts (Cambridge University Press, New York, 2020) 49.

24 Kraus, Theresa. Was FAA HQ the Site of a Notorious Slave Pen?

25 Ricks, 57.

Following Robert Armistead’s death, his widow, Susannah, began legal action to set aside the promised manumissions. Susannah complained to the District Court26 that her late husband was ill and lacked sufficient mental competency to make such important financial decisions. For the Bell’s, proving their freedom would be expensive, time consuming and uncertain at best.27 Daniel and Mary Bell, with the help of a few sympathetic whites, brought actions to challenge Susannah Armistead. Mrs. Armistead, however, ultimately prevailed and the District Court awarded her full title to the Bell children as “slaves for life.”28

26 Thomas, Ibid.

27 The Escape, The Pearl Coalition 2008 ttp://pearlcoalition.org/the-escape/

28 NARA RG 21, Entry 115, O.S. Case file, 1832, Robert Armistead. RG 21.

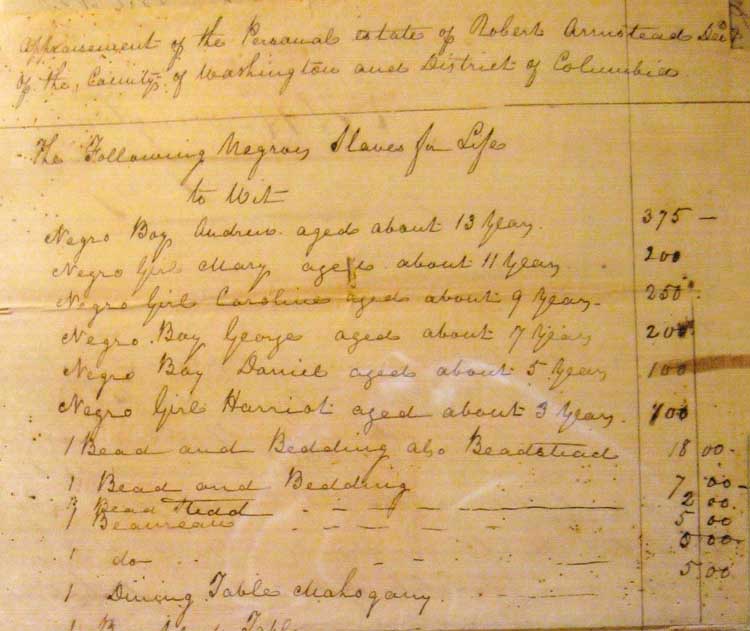

There is no record of the exact date Bell attained his freedom, however, the date is mostly likely sometime between 1846-1848. On 1 July 1848 Daniel Bell's name appears on a Petition for Freedom of his daughter, Harriet Bell, where he is listed as "her next friend Daniel Bell". The naming of Daniel Bell as Harriet's "next friend' signifies he was by that date a freeman."29 In July 1848, as part of the legal process Susan Armistead, offered the following financial appraisal as evidence of the Bell family worth to the estate of her late husband Robert Armistead.

29 Ricks, Ibid pp. 57-58.

Financial Appraisal of the Estate of Robert Armistead listing six children of Daniel

and Mary Bell as, “Slaves for Life”Transcription: "The Following Negroes Slaves for Life

To wit -

Negro Boy Andrew aged about 13 years 375 – Negro Girl Mary aged about 11 years 200 - Negro Girl Caroline aged about 9 years 250 – Negro Boy George aged about 7 years 200 – Negro Boy Daniel aged about 5 years 100 – Negro Girl Harriet aged about 3 years 100 –"3030 RG 21 Entry 115 O.S., Case File 1832 Robert Armstead National Archives and Records Administration Washington DC.

In the court documents Susannah Armistead revealed her need to raise money to pay debts and support her large family. The total value of the Robert Armistead’s estate was $1,299.95. However the majority of the amount, $1,225, was the value of enslaved Bell family. Fearing Robert Armistead's testamentary manumission would reduce her income, Mrs. Armistead began to make plans to sell the Bell children to slave dealers. Daniel Bell’s wages of $1.12 per day or about $30.00 per month were simply insufficient to ever purchase freedom for his wife and children.

The Schooner Pearl: Daniel and Mary Bell, desperate to save their family from being broken up and their children sold south, became primary organizers of the largest attempted mass slave escape. Daniel Bell joined another enslaved blacksmith striker Anthony Blow and freemen Paul Edmonson and Paul Jennings, in purchasing the aid of Captain Daniel Drayton of the Schooner Pearl, a Chesapeake Bay Schooner for the sum of $100.00 to help their families and other acquaintances flee north. In all seventy-six men, women and children attempted this perilous journey north. Tragically their daring plot was quickly foiled and all those aboard the Pearl were apprehended, including Daniel’s wife Mary, eight of the Bell’s children and two grandchildren. Slave escapes depended on secrecy and caution, the Pearl plan simply was simply widely known and rumors apparently circulated.

Mary & Emily Edmonson

shortly after they were freed in 1848The Pearl incident sent the District of Columbia white community into a panic. Large crowds of angry slaveholders and their supporters gathered and threatened violence against the black community and all abolitionists. In response, on 20 April 1848, the District of Columbia government posted handbills warning all citizens: "The peace and character of the Capitol of the Republic must be preserved"..."fearful acts of lawlessness and irresponsible violence can only agitate evil.”31 A contemporary account reveals how the fugitives were received once on shore.

31 Handbill "To the Citizens of Washington" dated 20 April 1848, Library of Congress Washington DC.

C

Washington DC Poste 1848 re Pearl"The steamer, with the sloop in tow, arrived at Piney Point about 7 o’clock. They reached the city at half past 7 yesterday morning, and after going within its jurisdiction, Mr. Williams being a magistrate of the same, summoned the parties before him and after hearing testimony, committed Sayres and Drayton for further examination which is to take place this day at 1 o’clock in the jail. The slaves were committed as runaways to be dealt with according to the law; - 39 men and boys, 26 women and girls and 13 children - 77 in all. When landed the prisoners were guarded by volunteers and marched in double file to the jail."32

32 The Washington Union (Washington, District of Columbia), 19 August 1848, p. 2.

There followed a list of the 77 enslaved men women and children along with the names of the respective slaveholders. The Bell family was listed as “Andrew, George Bell, Mary Bell, and her two children, Caroline and her two children, Mary Ellen and Harriet, the property of Mrs. Armistead.”33 The Bells and the other fugitives who had sought freedom on the Pearl were marched up Seventh Street as mobs of angry whites shouted derision and threats. Others threatened Drayton and Sayres with lynching. At the jail the Pearl’s women and children were held in one cell, while the men were placed in another.34

33 Ibid.

34 Drayton, Daniel, Personal Memoir of Daniel Drayton for Four years and Four Months (a Prisoner for Charity’s Sake) in Washington Jail (Bela Marsh, Boston, 1853), p. 40. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Personal_Memoir_of_Daniel_Drayton/NMslz6T_2DUC?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=seventh

Within the dark and dank jail cells, those from the Pearl were confined in the appalling heat of a Washington summer in deplorable conditions. Soon the slaveholders were allowed to reclaim “their property” and the Bell family was returned to Susannah Armistead as “slaves for life.” Luckily Daniel Bell, a freeman, had not gone with his wife and children aboard the Pearl. Instead Bell apparently had planned to meet his family later near the Maryland boarder. Consequently Bell was not incarcerated, although he was most likely interrogated as was his workmate blacksmith Anthony Blow. Blow, an enslaved blacksmith, was arrested and taken to Washington D.C. jail and later was sold to a family in Norfolk, Virginia.35 Susannah Armstead and other slave owners quickly reclaimed their "property" and made arrangements with slave traders to sell the fugitives. All the while Daniel Bell had to endure the horrible knowledge that his wife and children were now in jail or in the hands of slave dealers. Bell sought to purchase his family with the help of abolitionists and other sympathetic individuals, but he was only able to raise enough money to secure Mary and two of their younger children.

35 Still, William Still's Underground Rail Road Records: With a Life of the Author... Revised edition (William Still Publisher: Philadelphia, 1883), 61-63. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Underground_Rail_Road/8ANWAAAAcAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=anthony%20blow accessed 26 December 2020

During the trial of Captain Daniel Drayton, Bell's involvement in the escape was briefly and [stupidly] mentioned. Defense Attorney Horace Mann at one point "explained [to the jury] that the Bells had told some of their friends about fleeing slavery on the Pearl, and as a result Captain Drayton had far more fugitives than expected."36 While the trial ended with Drayton's conviction, Daniel Bell was fortunate in one respect as he was never charged with aiding or abetting the plot and was able to keep his job at the navy yard, although his wage was reduced from $1.20 per day to $1.12 per day.37 Daniel Bell through arduous effort over time purchased the freedom of various family members, but his son, young Daniel Bell, he never saw again, for Daniel had been sold south. Daniel and Mary Bell’s spent years, futilely searching for their stolen children.38

36 Ricks, 177.

37 Ricks, 177.

38 Sharp, John G., African Americans in Slavery and Freedom on the Washington Navy Yard 1799-1865 (Hannah Morgan Press: Concord, Ca. 2011), pp. 2-3.

Daniel Bell, blacksmith helper, 1.20 per day, Aulick to Bancroft 3 Jan 1846,

List of WNY employees to 31 Dec 1845Daniel Bell is listed on this WNY muster roll, as a blacksmith helper AKA striker for 1 January to 31 December 1845. A blacksmith's striker is an assistant (frequently an apprentice) whose job is to swing a large sledgehammer in heavy forging operations as directed by the blacksmith. See Aulick to Bancroft, 3 January 1846, Letters Received by the Secretary of the Navy from Captains (“Captains Letters”) 1805-1861, letter number 11, volume 326, RG 260, NARA Washington D.C. Following the recapture of the schooner Pearl, the Navy reduced Bell's daily wage from $1.20 to $1.12 per day.

Later Life: Following the events on the Pearl, Daniel Bell and his wife Mary continued to live in the District of Columbia. The 1850 Federal Census is the first to record both Daniel and Mary Bell as free blacks. The 1860 Federal Census records that Daniel Bell was 58 and working as a laborer at the Washington Navy Yard. His real property is valued at $1,500 and personal property $100.00. He died in Washington DC in 1877.39In the succeeding years, Daniel Bell, the navy yard blacksmith, and his wife Mary and their heroic role in organizing the dramatic 1848 voyage of the schooner Pearl was largely forgotten. Today, however, their courageous fight against injustice and their doomed but heroic attempt to save their family and friends is subject of renewed public and scholarly interest.40

39 Sharp, John G Last Will & Testament of Daniel Bell Genealogytrails 2008. http://genealogytrails.com/washdc/biographies/bio4.html

Last Will and Testament of Daniel Bell, 1877, Box 63, filed in the District of Columbia Orphan's Court (Probate Court).40 Chris Myers Ash & George Dereck Musgrove Chocolate City: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation's Capital (University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill 2017), 90.

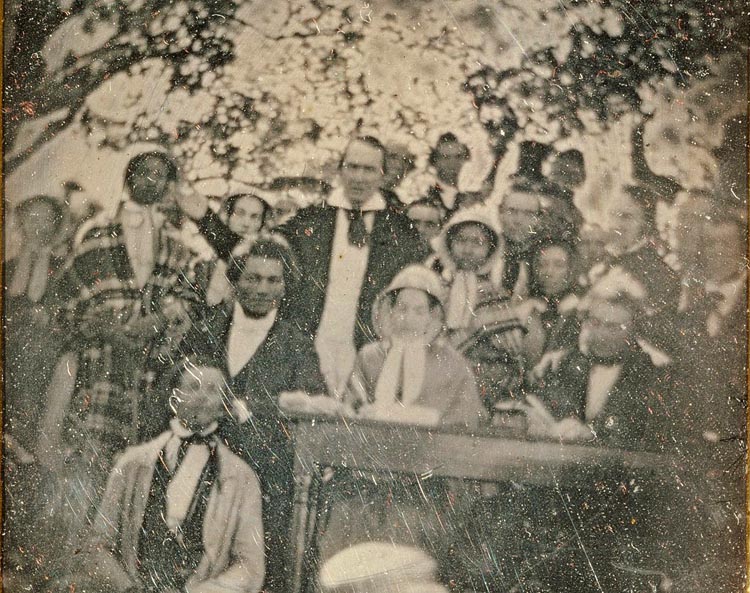

Fugitive Slave Law Convention, 1850 Cazenovia, New York

Mary (standing) and Emily (seated) Edmonson

* * * * * * * * * *

John "Jack" G. M. Sharp resides in Concord, California. He worked for the United States Navy for thirty years as a civilian personnel officer. Among his many assignments were positions in Berlin, Germany, where in 1989 he was in East Berlin, the day the infamous wall was opened. He later served as Human Resources Officer, South West Asia (Bahrain). He returned to the United States in 2001 and was on duty at the Naval District of Washington on 9/11. He has a lifelong interest in history and has written extensively on the Washington, Norfolk, and Pensacola Navy Yards, labor history and the history of African Americans. His previous books include African Americans in Slavery and Freedom on the Washington Navy Yard 1799 -1865, Morgan Hannah Press 2011. History of the Washington Navy Yard Civilian Workforce 1799-1962, 2004.

https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/browse-by-topic/heritage/washington-navy-yard/pdfs/WNY_History.pdf

and the first complete transcription of the Diary of Michael Shiner Relating to the History of the Washington Navy Yard 1813-1869, 2007/2015 online:

https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/d/diary-of-michael-shiner.html

His most recent work includes Register of Patients at Naval Hospital Washington DC 1814 With The Names of American Wounded From The Battle of Bladensburg 2018,

https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/r/register-patients-naval-hospital-washington-dc-1814.html

The last three works were all published by the Naval History and Heritage Command. John served on active duty in the United States Navy, including Viet Nam service. He received his BA and MA in History from San Francisco State University. He can be reached at sharpjg@yahoo.com