Letters from and to the Philadelphia Navy Yard 1826-1840

By John G. M. Sharp

At USGenWeb Archives

Copyright All right reserved

Philadelphia Navy Yard 1842, J. T. Bowen

Introduction: These transcribed letters and documents to the Secretary of the Navy and Board of Navy Commissioners provide a unique portal to the naval station’s formative years, 1826-1840, and rough beginning. Most of these letters were written by naval officers assigned to the navy yard. They describe the officers, the seamen and daily events of the Philadelphia Navy Yard. The authors typically wrote to the Navy Yard Commandants or the Secretary of the Navy on important and troubling events which had occurred. Their concerns and anxieties, especially those about race and ethnicity, often went far beyond Navy Yard, Naval Hospital or the Philadelphia Naval Rendezvous. The subject matter of their letters included race, ethnicity, employment, military housing, desertion, anxious parents and more.

A topic that occupied many of the early letters was recruitment. Surprisingly, as scholar Lauren McCormack has noted, we know very little about how sailors were recruited during the first years of the United States Navy.1 A letter of Commodore James Barron of 24 January 1833 to the Secretary of the Navy, forwarded a letter from Thomas Newell, the head of the Philadelphia Naval Rendezvous, warning against the recruitment of “foreigners.” Newell specifically listed immigrant recruits from England, Spain and Italy as most concerning.

1. McCormack, Lauren. “Food and Drink in the U.S. Navy, 1794 to 1820” USS Constitution Museum, 2018,

https://www.usscm.org/publications/us-naval- recruiting-during-the-war-of-1812.pdfDuring the 1830’s, free African Americans entering the Navy increasingly stoked white fears (see the letters of Commodores William Bainbridge and James Barron). On 14 September 1827, Bainbridge ordered the officers of the Philadelphia Naval Rendezvous not to accept any more blacks. Similarly on 5 February 1833, Barron forwarded and endorsed a 20 January 1833 letter of Thomas Newell seeking to limit the number of blacks accepted for the Navy.

The location of the Naval Rendezvous in Southwark was the subject of complaints by neighborhood residents (see Commodore James Barron to Secretary of the Navy 1 January 1833).

The letters of Commodores William Bainbridge of 11 September 1827 and James Barron to the Secretary of the Navy of 21 January1833 and 29 March 1834, highlight desertion as a continuing problem in the antebellum Navy.Chronic alcoholism, “intemperance”, and its effects on Boatswain Simon Jordan's job performance is discussed in a letter from Commodore William Bainbridge to Secretary of the Navy Southard on 7 November 1828.

The letter of Commodore James Barron of 24 March 1836 to the Secretary of the Navy provides a glimpse of the problem he had with Benjamin King a superannuated (he was in his 80’s) and well-connected master blacksmith. King was able to garner support from former President James Madison (28 May 1836) and LTC Samuel Miller (30 April 1836), a hero of the Battle of Bladensburg.

The environment is the subject of a unique letter from Dr. Thomas Harris, USN, who wrote to James Barron on 31 May 1832 with a plea to protect grounds behind the Philadelphia Naval Asylum les “Drunken & reckless carters will disregard fences, grass, fir and ornamental trees and everything which is calculated to give security & value to the estate.”

During this period, the Department of the Navy had neither a centralized recruitment service nor record keeping for enlisted personnel. Each naval vessel or shore station was responsible for enlisting the necessary seamen and petty officers to fill out the requisite crew. Prior to signing on, new recruits were interviewed by one of the ship’s officers or boatswain regarding their maritime experience and their health was verified by a physician. The Department of the Navy only began formal rendezvous reports in 1846. These reports record the number of men enlisted at a given recruitment station. Typically, reports listed the recruit's name, rate, rendezvous (recruitment station or vessel), date of enlistment, place of birth, age at time of enlistment and a physical description. Except for men who served in the American Revolution, there are no compiled central service records for sailors in the U.S. Navy, prior to 1846.2

2. Sailors in the United States Navy, 1798–1885, National Archives and Records Administration, https://www.archives.gov/files/research/military/navy/navy-sailors-records-1798-1885.pdf

Transcription: This transcription was made from digital images of letters and documents received by the Secretary of the Navy, NARA, M125 “Captains Letters” National Archives and Records. In transcribing all passages from the letters and memorandum, I have striven to adhere as closely as possible to the original in spelling, capitalization, punctuation, abbreviation, superscripts, etc., including the retention of dashes and underlining found in the original. Words and passages that were crossed out in the letters are transcribed either as overstrikes or in notes. Words which are unreadable or illegible are so noted in square brackets. When a spelling is so unusual as to be misleading or confusing, the correct spelling immediately follows in square brackets and italicized type or is discussed in a foot note.

“Our memory is a more perfect world than the universe; it gives life back to those who no longer exist.”

Guy de MaupassantJohn G. M. Sharp, 24 February 2022

* * * * * *

Definitions of Naval Ratings

Boy: In the early navy, "young boys" means just that they were young males, typically between thirteen and seventeen years of age. These young sailors-in-training were to be instructed in steering, heaving the lead, knotting and splicing, in rowing, in the use of the palm and needle, etc., that they might become qualified for higher rating as seamen and petty officers. During combat they ran powder to the guns, a critical but dangerous task. Most boys were usually rated as ordinary seaman at age 17 or 18. Boys were subdivided into three ratings: first, second and third with corresponding and increasing wages of $8, $9 and $10 per month.

Landsman: abbreviated “Lds.” Landsman was the lowest rank of the United States Navy in the 19th and early 20th centuries. It was given to new recruits with little or no experience at sea and, typically, men were over seventeen years of age. Landsmen performed menial, unskilled work aboard ship, like loading and offloading ships, and did most of the cleaning. A Landsman who gained three years of experience or re-enlisted could be promoted to Ordinary Seaman. The rank existed from 1838 to 1921. The rate of pay for landsman during the Civil War was $12 per month.

Ordinary Seaman: “O.S.” Ordinary seaman was the second-lowest rank of the nineteenth century United States Navy, ranking above landsman and below seaman. An ordinary seaman’s duties aboard ship included “handling and splicing lines, and working aloft on the lower mast stages and yards.

Seaman: ‘Sea.’ In the Navy, a seaman was an experienced mariner with usually four or more years work at sea. A seaman was expected to “know the ropes”, that is the name and use of every line in the ship’s riggng, and could be promoted to seaman. The seaman was expected to have expert knowledge of the various battle stations, armament and small boat handling. The rate of pay for seamen during the Civil War was $18 per month.

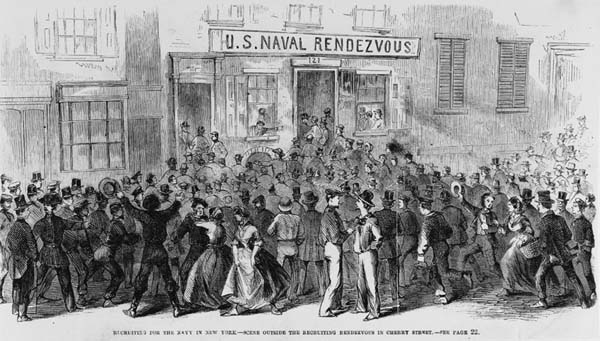

New York City Naval Rendezvous, 1861, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated WeeklyThe Philadelphia Naval Rendezvous was in perpetual competition with the merchant marine to recruit experienced seamen for the crews of naval vessels. The Navy relied heavily upon men who had made their start at sea in the merchant service first.3 The newspaper advertisement below provides some idea of the wages and terms in merchant vessels. 4

3. McKee, Christopher, Ungentle Goodnights Life in Home for Elderly and Disabled Naval Sailors and Marines and the Perilous Seafaring Careers that Brought Them There, (Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, 2018), p. 97.

4. United States Gazette for the Country, (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), 5 June 1833, p. 2.

Philadelphia Merchant Mariners: Unlike the U.S. Navy, service aboard merchant vessels offered seamen higher pay and some choices as to vessels, ports and routes. This was particularly important to Philadelphia seamen during the harsh winter months when seasonal storms and choppy waters of the north Atlantic increased sailing time and danger to both ship and crew. To induce these men, merchants typically offered higher wages and advances to get seamen to sail to the northern ports. Before the creation of regular enlisted career paths and a retirement system, it was common for mariners to have served in both the merchant and naval service. After reviewing 128 beneficiaries of the Naval Asylum Philadelphia for his Ungentle Goodnights: Life in a Home for Elderly and Disabled Naval Sailors and Marines and the Perilous Seafaring Careers that Brought Them There, scholar Christopher McKee found that 83 or 65% had merchant service before turning to the navy as a career.5 One 1810 survey of merchant crew lists from Philadelphia showed 2, 524 seamen and of these 378, or 15%, were African American and by 1812 they up 17%.6

5. McKee, Christopher, Ungentle Goodnights: Life in a Home for Elderly and Disabled Naval Sailors and Marines and the Perilous Seafaring Careers that Brought Them There (Naval Institute Press: Annapolis, 2018), p. 95.

6. Dudley, William S., Inside the US Navy of 1812-1815, (Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore, 2021), p. 253.

As early as 16 October 1826, Commodore William Bainbridge recommended to the Secretary of the Navy, Samuel L. Southard,

As to bounty, I believe there is scarcely a difference of opinion as to the advantages that would result in obtaining seamen among the officers who have had experience in procuring them under its influence. In the war with France & sometime after bounty was given & crews were readily obtained, notwithstanding the enormous wages ($30 & upward per month) then paid in the merchant service.

Bainbridge then commented to Southard, “I know that in four years a person can become an able seaman – that it is ample time to make him one for the general duties of an able seaman on board of a vessel of war.”7

7. Bainbridge to Southard 16 October 1826, Letters received by the Secretary of the Navy from Captains (“Captains Letters”), 1805-1861; 1866-85, 14 October 1826 to 27 November 1826, Volume, 108, Letter number 4, p. 3, RG 260, Roll 0108, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

Seamen’s Protection Certificates: We know a great deal more about the age, physical appearance and ethnicity of Philadelphia mariners, thanks to the Seamen’s Protection Certificates which were issued beginning in the early 1800s in an attempt to protect U.S. sailors from being pressed into service on British ships.8 These certificates contain the name of seaman, name of witness, age, place of birth, residence at the time of declaration, port and date of declaration and physical description.9 Seamen Protection Certificates were also known as "Seamen's Certificates,” "Sailor's Protection Papers," “U.S. Citizenship Affidavits" and popularly known as “protections”. From such certificates we learn that long-term seafarers were shorter than other Americans at 65.7 inches (5 feet 5 inches), indicative of poverty and straightened circumstances. Some 217 of the white mariners were, on average, 1.7 inches shorter than recruits in the Continental Army. Many of the 500 mariners were barely able to read or write. Of the 486 white or black sailors who were recorded as native born, 184 were unable to sign their names and 207 were barely able to write their names, making a total of 391 (80%) who were, at best, barely literate.10

8. Proofs of Citizenship Used to Apply for Seamen's Certificates for the Port of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1792–1861, NARA Microfilm publication M1880, 61 rolls, Records of the U.S. Customs Service, Record Group 36, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

9. Sharp, John G. M. American Seamen’s Protection Certificates & Impressment

1796-1822, http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/aspc&i.html

10. Newman, Simon P., Embodied History: The Lives of the Poor in Early Philadelphia,

(University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, 2003), p. 110.These documents were issued to American seamen during the last part of the 18th century through the first half of the 20th century. The surviving certificates and related documents convey important information about nautical life and its dangers in the early maritime world. These records, which cover the period 1796-1861, more than any other, allow us to see beyond the stereotypical, happy-go-lucky Jolly Tar of the “Great Age of Sail or the fiction of Hollywood. Instead these certificates reveal “the short and simple annals of the poor”, for a life at sea, as revealed in these certificates, was anything but romantic. For Philadelphia seamen their years afloat were rough, hard, low paying and dangerous; yet there remains clear evidence that many loved and took pride in their occupation.11, 12

11. Dye, Ira. “Early American Merchant Seafarers.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 120, no. 5, American Philosophical Society, 1976, pp. 331–60, http://www.jstor.org/stable/986266

12. McKee, Christopher. “Foreign Seamen in the United States Navy: A Census of 1808.” The William and Mary Quarterly, vol. 42, no. 3, Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1985, pp. 383–93, https://doi.org/10.2307/1918933

Among the Seamen's Protection Certificates in the collection of the National Archives and Records Administration, one pattern immediately catches the eye. There are a large number of African American seamen from Philadelphia variously described in the language of the time as “black, mulatto, Sambo, yellow or colored”. They accounted for almost a third of the applications in NARA’s collection and far in excess of their proportion of the population. For black Americans, these documents fulfilled two purposes. First, they were proof of their status as freeman, and secondly, they served as protection against enslavement. Sometimes these identity papers were borrowed by an enslaved person. One famous example, Frederick Douglass, borrowed a certificate in 1838 and walked away to freedom.

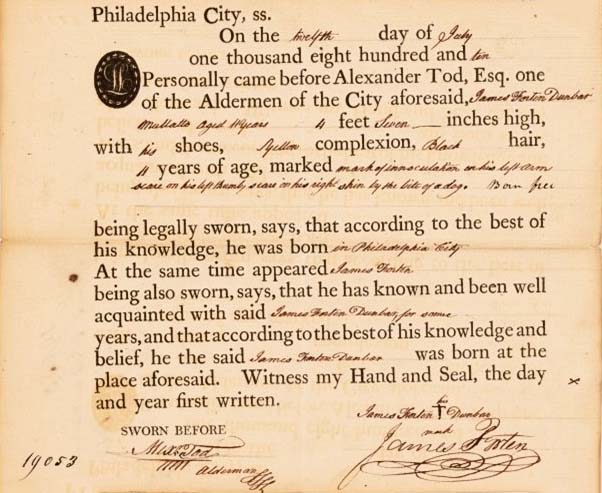

James Forten Dunbar: The 12 July 1810 protection certificate (below), issued in Philadelphia identifies the bearer as James Forten Dunbar, a “mulatto” (a person of mixed white and black ancestry), age eleven and height 4’ 7’’ inches tall. Dunbar was described as having black hair and yellow complexion. He had a smallpox inoculation scar on his left arm and on his right shin the mark of a dog bite. Dunbar was born a “free man of color” in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on 1 July 1799. Dunbar was the fourth and last child of William Dunbar and Abigail Forten Dunbar. His mother, Abigail, was the sister of famed African American abolitionist, sailmaker and father, James Forten. Dunbar’s father William died young, and it’s his uncle, the renowned James Forten, who signed for and made sure “Born Free” was included in the description. While young James Dunbar’s initial voyages were probably confined to smaller vessels which worked the Delaware River or the immediate coast, a protection certificate offered proof of his status as free black and could be useful to establish his identity to local authorities and police.

James Forten Dunbar, certificate 12 July 1810Dunbar attested the document by his X mark; it is unclear if he ever became fully literate. Dunbar would spend most of his life as a sailor aboard merchant vessels and such naval vessels as the USS Constellation, USS Niagara, USS Brooklyn and the USS Tuscarora.

At the beginning of the Civil War, the Union Navy desperately wanted experienced seamen. Dunbar left the Philadelphia Naval Asylum and rejoined the navy he loved and where he served throughout the Civil War. At the time of his reenlistment in July 1863, he is listed at age 63, enlisting for three years. He is recorded as 5' 5 & 1/4" tall. Dunbar listed 37 years of naval service, and his occupation was sail maker. The recruiting officer noted Dunbar, like many "old salts", was heavily tattooed with a ship, mermaids, a man and a woman and family group. While serving on the USS Tuscarora, he took part in some of the most memorable events of the Civil War, serving as a sailor in Admiral David Dixon Porter's attack on Fort Fisher in December 1864 and January 1865. James Forten Dunbar died 26 November 1870 and was buried at Philadelphia Naval Asylum burial grounds.

Anderson B. Jackson was born circa 1795. Jackson alternated between the merchant marine and naval vessels. Jackson was described as Black and/or "Mullatto" on various documents. While serving on the USS United States he was reported as absent without leave and a reward notice (see above) was issued. A careful check of this document revealed this was not the case. In June 1819 John de Bree, purser of the frigate USS United States, believed, based on faulty information, that the two seamen were absent without leave, and subsequently had a notice posted in the Norfolk papers on Saturday, 12 June 1819. The announcement offered a reward of $10 for each of Andrew (sic) Jackson (1800 - after 1870) and William Preece.13 A check of the 1819 muster rolls and payroll of the frigate, however, reflect both seamen had been recently promoted and paid off.

13. American Beacon and Norfolk-Portsmouth Daily Advertiser (Norfolk, VA), 12 June 181,9 p. 1.

The USS United States had served in the Mediterranean with the U.S. Naval Squadron for a long cruise and returned to Hampton Roads, Virginia, on 18 May 1819. Most of her crew of nearly 900 men would leave when she decommissioned on 9 June 1819 and to be laid up at Norfolk.14 Since their ship was to be placed in ordinary, both of these able seamen rapidly found work on other vessels. Somehow in the pursers haste to complete the necessary payroll and muster records; Jackson and Preece were mistakenly reported as deserters. Payroll and muster records though reveal both William Preece and Anderson Jackson had previous maritime voyages and apparently both men found naval life congenial. By modern standard, life in the U.S. Navy in 1819 was harsh and exacting. However, for many men, having a place to live with three meals a day, grog ration twice daily and free medical care with a physician aboard to treat their aliments made the nautical life bearable and to some quite agreeable.

14. Hill, Frederic Stanhope, Twenty-Six Historic Ships (New York and London: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1905), 206.

https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_aAMKAAAAIAAJOn his certificate issued in Philadelphia 9 May 1827, he is described as age 32, free black, with wooly hair, five feet 9 and ½ inches tall, with a scar under the right eye. Jackson had made his X attesting to the facts stated. Jackson was born in Washington City and his certificate is attested by Elizabeth Ohnsman, perhaps a friend, with her X.

William Negley: This certificate (above left) issued in Philadelphia 30 October 1822, born 1774, age 48, height, 5’ 4’’, brown hair, blue eyes, scar on left knee, Letters NW on left arm. Negley signed his signature, his witness made his X.

John Baker: This protection certificate (above right) was issued in Philadelphia on 5 July 1805 to John Baker. Baker is described as a native of Philadelphia and a citizen of the United States. Baker is listed as twenty years of age, five feet eight inches tall, long brown hair, and brown complexion. His tattoos included two bread fruit trees (showing his time in Tahiti or Samoa) on his description, noted his right arm has a “small scar on his left thigh occasioned by the cut of a cutlass and also has a mark on the inside of his left leg." Baker attested the certificate with his signature and as did his friend John Plover. In an era with no photo images, tattoos by the early nineteenth century were one means of clearly establishing the identity of a seaman. “In a sample of 846 seamen who applied for protection certificates, from 1796 to 1803, an impressive 21% had designs, symbols, their names, dates and or initials pricked into their skin.”15 Tattoos were widespread with mariners. Novelist Herman Melville, who served aboard whaling vessels and the frigate USS United States, recounts the practice of “pricking” or tattooing aboard that vessel in 1844.16

15. Dye, Ira. “The Tattoos of Early American Seafarers, 1796-1818.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 133, no. 4, American Philosophical Society, 1989, pp. 520–54, http://www.jstor.org/stable/986875

16. Melville, Herman, White Jacket or the World in a Man-of-War, editor Thomas Tansselle (Library of America: New York 1983), p. 525.

William Butler: a free black sailor was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1807. In his certificate issued 26 April 1834 (above left) Butler is described as, 5 feet 7 ½ inches tall, dark complexion, identifying marks scars on his forehead and on left ear.

John Evans This protection certificate (above right) was issued in Philadelphia on 12 November 1813 to John Evans. Evans is described as twenty one years of age, five feet 7 inches high, dark hair, dark complexion. He was listed as having a scar on the left hand and a scar on the calf of the right leg, and “an eagle and anchor on the back of the right hand done with Indian ink.” Evans was born in Norfolk, Virginia. Evans was literate and signed his name, as did his witness Michael Robinson.IMAGE

Peter Till protection certificate 11 August 1826Peter Till: This protection certificate was issued in Philadelphia (above) on 11 August 1826 to Peter Till, a formerly enslaved black man. Till was enumerated free, black, age twenty-nine, height five feet 6 inches tall and born in Sussex County, Delaware, about 1797. Noted too are dog bite scars below Till’s right elbow. “The said Peter Till produced a certificate of his having been manumitted and set free by Benjamin Robinson, a citizen of the State of Delaware to whom he had formerly been sold for a term of years by his original owner David Hopkins of said State, the proof of his freedom being duly recorded in the Orphans Court for the City and County of Philadelphia.17 Peter Till died 26 March 1839 and he is buried in Bethel Church Burial Ground, Philadelphia.18

17. Dixon, Ruth Priest, “Genealogical Fallout from the War of 1812” Spring 1992, Vol. 24, No. 1, Genealogy Notes, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/1992/spring/seamans-protection.html

18. Ancestry.com. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S., Death Certificates Index, 1803-1915 [database online]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.

* * * * * *

Commodore William BainbridgeLetters of Commodore William Bainbridge and James Barron: The letters below from Commodore William Bainbridge and Commodore James Barron discuss their efforts to recruit a sufficient number of sailors at the Philadelphia Naval Rendezvous and to limit the number of African Americans enlisting or entering the Navy.

Restrictions on the enlistment of African Americans began in August 1798 when the Secretary of the Navy, Benjamin Stoddert, banned all “negroes and mulatoes [sic]” from naval service19 On 3 March 1813, the Navy officially reversed the August 1798 ban on African American sailors in the fleet, allowing for “persons of color” to serve on “public vessels” of the United States.20 Since the U.S. Navy did not designate race on any official documents quantifying the number of black sailors serving aboard U.S. naval vessels, is an ongoing subject of debate. Anecdotal accounts from the time period suggest that anywhere from 15 to 50 per cent of any given U.S. naval vessel’s crew were of African descent. The USS Independence, while in Boston Harbor in 1814, had 34 black crew members out of its total complement of about 215 sailors [15.8 percent].21Officially, from 1798 until 1813, African Americans were banned from enlistment, though the practice was largely determined by a vessel's commanding officer and wartime necessity.2219. Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Stoddard to Lt. Henry Kenyon, 8 August 1798, Naval Documents Related to the Quasi-War Between the United States and France, (Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 1935), Volume I, p. 281.

20. Altoff, Gerard T., Amongst My Best Men: African-Americans and the War of 1812 (Put-in-Bay, OH: The Perry Group, 1996), p. 20.

21. Bearss, Edwin C., Historic Resource Study, Volume I and II, Charlestown Navy Yard, 1800-1842 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1984), p. 154.

22. McCormack, Lauren, “Black Sailors During the War of 1812,” USS Constitution

Museum, 2020, https://ussconstitutionmuseum.org/2020/02/21/black-sailors-during-the-war-of-1812/

* * * * * *

Commodore James BarronCommodore James Barron (1768-1851) was commanding officer of the Philadelphia Navy Yard from 7 March 1831 to 1837. As commandant of the Naval Yard, Barron also had supervision of the Philadelphia Naval Rendezvous and its head, Master Commandant Thomas Madison Newell (1800-1873). One of Barron’s principal responsibilities was to provide oversight of Newell and the Philadelphia Rendezvous.

To accomplish their recruitment objectives both Bainbridge and Barron relied heavily on the Philadelphia Naval Rendezvous (temporary recruiting center) which, as Barron reported, was only opened intermittently from 1809 to 1832.

IMAGE: James Barron’s 1832 report to the Secretary of the Navy re Philadelphia Naval Rendezvous

On 31 March 1832 Commodore Barron reported that during this time period the Rendezvous had recruited a total of 1,635 men. He then clarified that the Rendezvous was open only as needed during this period for a total time of four years and three months.23

23. Barron to Woodbury, 31 March 1832, Letters received by the Secretary of the Navy from Captains (“Captains Letters”), 1805-1861; 1866-1885, 1 Jan 1832 to 31 Jan 1832, Letter number 115, p. 2, RG 260, Roll 0168, National Archives and Records Administration,Washington, D.C.

Arch Street Ferry, Philadelphia, 1800, William Birch, LOCFear of Foreigners: On 24 January 1833 Commodore Barron forwarded to Secretary of the Navy, Levi Woodbury, Thomas Newell’s complaint regarding “Foreigners and more particularly of English, Spaniards and Italians, there are a great number of this Class of Seaman… with a preference over our native seamen as in the Appointment of Petty Officers &c.”24

24. Newell to Barron.

Such fears were not new, as early as 1817 the Board of Navy Commissioners, reacting to rising nationalism and perceived security threats, directed, “None but citizens of the U.S. are to be employed in any situation in the Navy Yard under your command. Should there be any such at present employed they are to be discharged.”25 The Board stated, “This regulation was founded on the Supposition that Citizens will be less likely to betray secrets and convey to the Enemy such information that will tend to the disadvantage of the U.S.”26 The Board allowed some Philadelphia Navy Yard employees to retain employment if they could provide a certificate of naturalization. All shipyard commandants were required to examine the supporting paper work, although it is unclear as to how rigidly this was enforced.27

25. Circular to Commandants, E 307, volume 1, April 1817, RG 45, Board of Naval Commissioners, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

26. BNC Journal, E303, v. 1, 1 April 1817, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

27. Sharp, John G. M., The Gosport Navy Yard Apprentice Boys School and the question of foreign birth, June 7, 1839 http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/nnysharp7.html

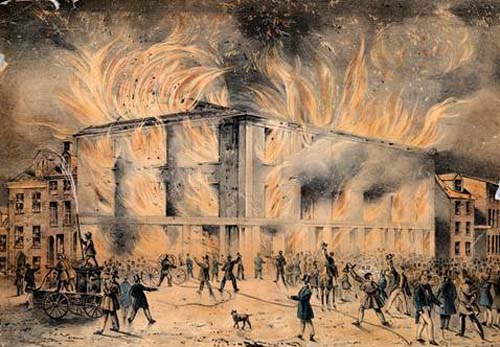

While there was opposition from some anxious that many innocent men would be dismissed, the mandate that only citizens be employed remained in effect. In the 1830’s nativism, that is the fear and hatred of aliens particularly religious or ethnic minorities, began to surface in American politics which took shape in fear of immigrants. By the 1830’s as immigration from Ireland and Germany swelled the Catholic population, anti-Catholicism increased along with suspicion of all those of foreign birth.28 These culminated in the Philadelphia nativist riots (also known as the Philadelphia Prayer Riots, the Bible Riots and the Native American Riots) which were a series of riots that took place on May 6–8 and July 6–7, 1844, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States, and the adjacent districts of Kensington and Southwark. The riots were a result of rising anti-Catholic sentiment at the growing population of Irish Catholic immigrants. The government brought in over a thousand militia — they confronted the nativist mobs and killed and wounded hundreds.29

28. Geffen, Elizabeth M., "Violence in Pennsylvania in the 1840s and 1850s." Pennsylvania History 36.4 (1969): 381–410, quoting p. 392.

29. Grubbs, Patrick, "Riots (1830s & 1840s)" Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia (2018)

https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/riots-1830s-and-1840s/Efforts to Limit Recruitment of Blacks: On 5 February 1833 Commodore Barron forwarded yet another complaint from Newell to Woodbury regarding the number of African Americans entering the Navy. Commodore Barron endorsed Newell’s complaint adding:

I am inclined to believe that a greater portion of them have been induced into our Ships than good policy Justified. ...Captain Newell now informs me that a great number of those people daily offer themselves at the Rendezvous; and had requested me to ask of you, to be pleased to say to what extent you are desirous to encourage, or to limit this practice –

In making their request neither man was neutral, both were slaveholders, seeking limits or restriction on the number free black men allowed to enlist.30, 31 James Barron had grown up near Norfolk Virginia. The Barron family was composed of numerous military officers and wealthy planters, most of whom were slaveholders. The 1830 U. S. Census for Portsmouth, Virginia, reflects Commodore James Barron enumerated as a slaveholder with three enslaved persons. Master Commandant Thomas M. Newell came from a slaveholding family in rural Georgia. On the 1850 U.S. Census, Thomas Newell is enumerated as a slaveholder with thirteen enslaved individuals. Despite Barron’s unwillingness to employ blacks as seamen, in 1830 while commandant of the Gosport (Norfolk) Navy Yard, he had employed two enslaved women, Rachel Barron and Lucy Henley, as "Ordinary Seamen” on the Navy payroll and routinely signed and pocketed their wages.32

30. The National Archives in Washington, D.C.; NARA Microform Publication: M432; Title: Seventh Census of the United States, 1850; Record Group: Records of the Bureau of the Census; Record Group Number: 29. Thomas M. Newell was enumerated as a slaveholder with thirteen enslaved individuals.

31. 1830, Census Place, Portsmouth, Norfolk, Virginia; Series: M19; Roll: 197; Page: 352; Family History Library Film: 0029676. James Barron is enumerated as a slaveholder with three enslaved individuals.

32. Miscellaneous Records of the Office of Naval Records and Library, 1803-1859, 1830 Norfolk, Virginia, Roll 0183, RG -45, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

Such racist ideas, however, were not limited to the slaveholding south.33 On 14 September 1827, Commodore William Bainbridge, a native Philadelphian and commandant of the Philadelphia Navy Yard, informed the Secretary of the Navy,

I have the honor to acknowledge the receipt of your letter of the 10th instant – and have the pleasure to inform you that no recruits have been sent from this Station since my present command here – I have since given very strict instructions to Master Commandant Hunter, who commands the Receiving Ship - and I have sent a copy of your letter to Master Commandant Conner of the Rendezvous for his Government. Finding that 18 blacks had been entered in the Total number of 102 – I ordered Recruiting officer not to enter anymore until further orders.

33. William Bainbridge to Southard, 14 September 1827, NARA M125, “Captains Letters” 30 July 1827 to 6 Oct 1827, letter 51.

Philadelphia in the early 1830's: The decade of the 1830’s saw “heightened concern with order and disorder”, as immigrants arrived in large numbers.34 Commodores Bainbridge and Barron were not alone; many naval officers and white citizens held similar views. Philadelphia in the 1830’s was home to the largest free African American population in the country and to large numbers of recent Catholic immigrants from Ireland and Germany. Both factors exacerbated economic, ethnic and racial tensions during the 1830’s and 1840’s. The black population in Philadelphia and its surrounding suburbs more than doubled in the first three decades of the nineteenth century, from 6,880 in 1800, to 15,624 in 1830. Coinciding, but not caused by this growth, was the increase in the abolitionist movement.35

34. Hammett, Theodore M., “Two Mobs of Jacksonian Boston: Ideology and Interest” The Journal of American History, Vol. 62, No. 4 (Mar. 1976), pp. 845-868, Oxford University Press.

35. Grubbs, Patrick, “Riots of the 1830’s and 1840’s” The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/riots-1830s-and-1840s/

The Flying Horse Riot: On August 11, 1834, a group of white and black citizens quarreled over seats on a merry-go-round known as the “flying horse’s riot” near Seventh and South Streets. The next evening as rumors spread that black residents had insulted whites, fighting resulted in the destruction of the carousel. Over the course of the next three nights, the African American communities of Philadelphia were terrorized as pro-slavery white mobs demolished black churches and forty-five private buildings.36, 37

36. Runcie, John. “‘Hunting the Negros in Philadelphia: the Race Riot of August 1834.” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies, vol. 39, no. 2, Penn State University Press, 1972, pp. 187–218, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27772015

37. “Policing the Pre-Civil War City,” Digital History 2021, https://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/topic_display.cfm?tcid=101

These 1834 riots were not the end, for African Americans would remain the target of white mobs throughout the 1830s. In August 1835, a strike at the Washington Navy Yard quickly morphed into a race riot.38 Similar riots occurred in other port cities. On 7 July 1834, New York City was torn by a huge anti-abolitionist riot (also called Farren Riot or Tappan Riot) that lasted for nearly a week until it was put down by military force. At times the rioters controlled whole sections of the city while they attacked the homes, businesses and churches of abolitionist leaders and ransacked black neighborhoods.39 In Boston in 1835, the so-called “Gentleman’s Riots” convulsed that city.40

38. Sharp, John G. M., The Washington Navy Yard Strike and "Snow Riot" of 1835, http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/washingtonsy.html

39. Jentz, John B. (June 1981). "The Antislavery Constituency in Jacksonian New York City". Civil War History, 27 (2): pp. 101–122.

40. Hammett, Ibid, p. 845.

The 1838 Riot culminated in the burning of Philadelphia’s Pennsylvania Hall. During all of these attacks, rioters invaded African American homes, looted businesses and burned churches. After the 1838 riot, the reaction of Philadelphia government leaders was to criticize abolitionists and blacks.41 In 1838, white fears led Pennsylvania voters to ratify a new state constitution restricting the vote to "white freemen" only.42

41. The Philadelphia Riots of 1844: Background Reading, Reporting Ethnic Violence in the City of Unbrotherly Love: Violence in Nineteenth-Century, https://www.hsp.org/sites/default/files/legacy_files/migrated/thephiladelphiariotsof1844.pdf

42. Smith, Eric Ledell, “The End of Black Voting Rights in Pennsylvania: African Americans and the Pennsylvania Constitutional Convention of 1837-1838,” pp. 279-296, Pennsylvania State University.

During the antebellum era, economic competition between blacks and whites for jobs inflamed racial prejudice especially in working class areas of Philadelphia. Tragically blacks in Pennsylvania would not regain their right to vote until the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1870.43

43. Lasko, David A. The Disenfranchisement of Black Pennsylvanians in the 1838 State Constitution: Racism, Politics, or Economics?—a Statistical Analysis, Pennsylvania State University, York Campus, p. 28, http://www2.york.psu.edu/~dxl31/research/articles/suffrage.pdf

Destruction by Fire of Pennsylvania Hall, 17 May 1838Black Sailors in the Navy and Merchant Marine: From the end of the War of 1812 until the Civil War, modern scholars have had little reliable data regarding the number of black men entering the naval service. The fortuitous discovery of a remarkable letter from Commodore Lewis Warrington, commandant of the Norfolk Navy Yard dated 17 September 1839, gives a better picture of the recruitment of African Americans during this period. Commodore Warrington was a vocal critic of black recruitment, writing "I deem it proper to represent to you what is considered a great inconvenience if not an evil, and that is the number of Negroes which are entered at various places for the general Service.”

Commodore Lewis WarringtonHowever, Warrington collected recruitment data from five port cities of Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore and Norfolk, and this is an important glimpse into the makeup of the antebellum era Navy. His 1839 report revealed that Philadelphia Naval Station had the highest level of blacks entering the service.

Philadelphia recruiting station entered a total of 176 men, “of which 39 were Blacks” for 22.1% of the total.

Boston recruiting station entered the least with 187 men “of which 13 were Blacks” for 6.95% of the total.

New York recruiting station entered 193 men total “of which 26 were Blacks” for 13.47% of the total.

Norfolk recruiting station entered 180 men total “of which 16 were Blacks” or 8.89% of total.

Baltimore recruiting station entered a total 280 men of which 25 were Blacks” or 8.93% of the total.44

44. Sharp, John G. M., The Recruitment of African Americans in the U.S. Navy 1839, Naval History and Heritage Command, 2019, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/r/the-recruitment-of-african-americans-in-the-us-navy-1839.html

Black Recruitment Restricted to Five Percent: On 13 September 1839, acting Secretary of the Navy, Isaac Chauncey, reacting to the complaints of Commodores Barron and Warrington, issued a circular to all Naval Stations declaring that, in view of complaints, the number of blacks in naval service would henceforth be no more than five percent of the total number entered under any circumstances and no slave was to be entered under any circumstances.45, 46

45. African American Sailors in the U.S. Navy, A Chronology Naval History and Heritage Command, https://www.history.navy.mil/browse-by-topic/diversity/african-americans/chronology.html

46. Acting Secretary of the Navy Isaac Chauncey Circular, September 13, 1839, Circulars and General Orders, I, 35, RG 45, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

During the War of 1812, though, Chauncey had written,

I have nearly fifty blacks on board of this ship, and many of them are among my best men; and those people you call soldiers have been to sea from two to seventeen years; and I presume that you will find them as good and useful as any men onboard of your vessel; at least, if I can judge by comparison; for those which we have on board of this ship are attentive and obedient, and, as far as I can judge, many of them excellent seamen: at any rate, the men sent to Lake Erie have been selected with a view of sending a fair proportion of petty officers and seamen; and I presume, upon examination, it will be found that they are equal to those upon this lake.47

47. Mackenzie, Alexander Slidell, Life of Perry (New York, 1840), volume I, pp. 165-166, 186-187.

In 1842, the Secretary of the Navy, A. P. Usher, answering a query from the Congress, replied that "no slaves were enlisted and that since Negros were not entered on a separate account, precise figures could not be given.”48

48. A. P. Usher to the Speaker of the House, August 10, 1842, in Executive Documents, Number 282, 27th Congress, 2nd Session, Volume V.

Navy Department

Washington, September 13, 183949Frequent complaints having been made of the number of blacks and other colored persons entered at some of the recruiting stations, and the consequent under-proportion of white persons transferred to sea-going vessels, it is deemed proper to call your attention to the subject, and to request that you will direct the recruiting officer at the station under your command, in future, not to enter a greater proportion of colored persons than 5 per cent, of the whole number of white persons entered by him weekly or monthly, and in no instance and under no circumstances whatever to enter a slave.

I. Chauncey,

Acting Secretary of the Navy.49. Aptheker, Herbert, “The Negro in the Union Navy.” The Journal of Negro History, vol. 32, no. 2, Association for the Study of African American Life and History, Inc., 1947, pp. 169–200, p. 173.

* * * * * *

Life at Sea: Philadelphia, in the 1830 U.S. Census, had a white population of 150,000, while the black population had grown to 14,500. Since its founding, Philadelphia was a seafaring city in which sailors were the largest occupational group.50

50. Newman, Simon P., Embodied History: The Lives of the Poor in Early Philadelphia,

(University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, 2003), p. 100.Life at sea was no romantic cruise for the men of the lower deck. The wages were low and living spaces damp and often cold. Food - unless supplemented by a fortuitously caught fish or seabird - was monotonous. One slept and ate next to sweaty men who bathed infrequently. Opportunities for leave ashore in foreign ports were scarce. Death or wounding from enemy action was far less of a danger than a shipboard accident or some strange disease.51

51. McKee, Christopher, Ungentle Goodnights: Life in Home for Elderly and Disabled Naval Sailors and Marines and the Perilous Seafaring Careers that Brought Them There, (Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland, 2018), pp. 159-160.

Given the hardships and peril of a nautical life, why did so many men and boys voluntarily enlist in the Navy? The answer as poet Thomas Grey concisely wrote is, “The short and simple annals of the poor.”52

52. Thomas Grey, Thomas Grey Archives, “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” 1751, https://www.thomasgray.org/cgi-bin/display.cgi?text=elcc

Despite numerous hardships, many Philadelphia men and boys were able to find work by enlistment in the Navy. For many, the structured life the naval service offered had some advantages, the pay, though low, was regular, they had three meals a day, the living spaces below decks, while rough and uncomfortable, were often better than a tenement hovel in Southwark, each ship normally had a qualified physician and two rations of grog per day that helped ease the pain.

* * * * * *

Transcribed Documents

Apprentices: were legally bound to their master for a specified period of time. In return, the master craftsman was legally obligated to impart knowledge of a trade, e.g. carpenter, shipwright, ship caulker.

For the commandants of the Navy Yard, the desertion of new recruits and able seaman was a constant worry and frustration, see, James Barron to Secretary of the Navy Southard, 19 April 1827, http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/nnysharp14.html

Barron attributed naval desertions “to the feeble state of the Marine guard attached to this Yard” and proposed stringent penalties. Their worries entailed more than simple desertion, for recruits often pleaded to the Secretary of the Navy, stating they were erroneously enlisted. Each month fresh queries made their way to Bainbridge and Barron’s desks from distressed parents seeking information or begging for their errant child’s discharge. Normally a recruits signature or X on an enlistment paper was legally sufficient; however, in law a bound apprentice could not be enlisted since the apprentice indenture was a binding legal document. William Crowder apparently was discharged because his age of 17 years required the consent of his parent or guardian.Navy Yard Philadelphia

9 July 1827 53Sir,

I have the honor to acknowledge your letter of the 6th instant relative to Wm Crowder with the enclosure from Thomas Marshall. I have examined the Boy and find him about 17 years of age – but he never was an indented apprentice – he has in his possession a letter from his mother who is very anxious for his discharge - I therefore respectfully recommend that he may be discharged - therewith return Mr. Marshall’s letter.I have the honor to be with great respect

Your obedient servant[Signed] Wm Bainbridge

53. Bainbridge to Southard, 9 July 1827, Letters received by the Secretary of the Navy from Captains ("Captains Letters"), 1805-1861; 1866-85, 14 May 1827 to 31 October 1827, Volume 112, Letter 44, RG 260, Roll 0112, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

* * * * * *

Navy Yard Philadelphia

14th September 1827 54Sir,

I have the honor to acknowledge the receipt of your letter of the 10th instant – and have the pleasure to inform you that no recruits have sent from this Station since my present command here – I have since given very strict instructions to Master Commandant Hunter, who commands the Receiving Ship - and I have sent a copy of your letter to Master Commandant Conner of the Rendezvous for his Government. Finding that 18 Blacks, had been entered in the Total number of 102 – I ordered Recruiting officer, not to enter anymore until further orders.

I have the honor Sir,

to be, very Respectfully

Your obedt Servt.Wm Bainbridge

To the Hon'ble

Samuel L Southard

Secretary of the Navy

Washington54. Bainbridge to Southard, 14 September 1827, Letters received by the Secretary of the Navy from Captains ("Captains Letters"), 1805-1861; 1866 -85, 30 July 1827 to 6 October 1827, Volume 113, Letter number 51, RG 260, Roll 0113, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

* * * * * *

Lyander W. Webb, musician and unhappy sailor,

IMAGE: Muster Roll USS Delaware, Number 194, Landsman, Lyander W. Webb, discharged 17 December 1827 at Norfolk Virginia 55

55. Miscellaneous Records of the Navy Department, Muster and Payrolls 1827, USS Delaware, Number 194, Lysander W. Webb, Roll 0098, p. 8, RG 45, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C .

Lyander Webb (1805 to June 1858), a resident of Philadelphia, enlisted in the Navy at the Philadelphia Naval Rendezvous in October 1827. On 31 October 1827, his mother, Elandan Webb, wrote to the Secretary of the Navy, Samuel L. Southard, to plead that her son, Lyander, and friends, on a “frolic” and under the influence of alcohol, had enlisted in the Navy, pleading that he be discharged on compassion grounds.

By the time her letter reached the Secretary Southard, young Webb had been moved to Norfolk, Virginia, and probably recovered his wits aboard the receiving ship USS Delaware then at anchor in Norfolk harbor.56 A family friend also wrote to appeal (5 November 1827) to Southard that Lyander Webb “was by profession an engraver of music and musician.”56. The third USS Delaware of the United States Navy was a 74-gun ship of the line, named for the state of Delaware. She was laid down at Norfolk Navy Yard in August 1817 and launched on 21 October 1820. She was roofed over and kept at the yard in ordinary until on 27 March 1827, when she was ordered repaired and fitted for sea.

Lyander Webb had, in fact, written, composed and published music. His “Grand Quick Step", performed by Johnson's Military Band, was published in 1827.57

57. Webb, Lyander, Grand Quick Step, performed by Johnson's Military Band; arranged for the piano forte by Lyander W. Webb [between 1824 and 1827, J. J. Rickers, 187 Broadway, New York, University of Pennsylvania, Colenda Digital Repository, https://colenda.library.upenn.edu/catalog/81431-p33776376

Webb’s 1827 “Grand Quick Step”Many of the young men who had arrived on the USS Delaware, like Webb from a middle class background, were recruited at the naval rendezvous in Philadelphia, in the District of Southwark. The Southwark Naval Rendezvous was located near the notorious waterfront and relied on “crimps”, men who recruited or ensnared unwary seaman or novices like Webb for bounty or fee. Many of these crimps operated out of boarding houses while others owned them. Crimps and the proprietor, often one-and-the-same, dispensed liquor and girls to the unwary seamen or landsmen at over-charged rates. This meant the debt could only be paid directly from the recruit signing the enlistment papers and signing over his three months advance wages at twelve dollars per month for able seaman, ten dollars for ordinary seaman and eight dollars for a landsmen to the crimp and tavern owner.58

58. Castleman, Bruce A., Knickbocker Commodore: The Life and Times of John Drake Sloat, 1781-1867 (State University of New York Press: Albany 2016) pp. 126-128.

Like Webb, once sober, not all naval recruits on the USS Delaware were satisfied in their new vocation. However, most were illiterate and lacked any connection to the Secretary of the Navy. Their transformation from civilian life to the rigors of military service afloat was harsh and some failed to adapt. Young Herman Melville, who, in 1843, shipped aboard the frigate USS United States as an Ordinary Seaman, found the recruits “could not have chosen a more rigidly hierarchical, oppressive, and undemocratic world” than a naval frigate. New recruits were shocked to learn obedience to orders was a requisite of naval life enforced by often brutal punishment.59

59. Robertson, Lorie, Melville: a Biography, (Clarkson N. Potter: New York, 1996), pp. 117 & 129.

Still, despite corporal punishment at sea such as flogging, or being beaten with a boatswain starter, many poor working-class men came to depend on the navy for a place to stay. The men found that the monotonous, but plentiful rations of salted meat (beef and pork), bread and vegetables, peas, rice, and their half pint of distilled spirits was a welcome daily ration. Modern nutritionists estimate the nineteen century naval sailor’s diet contained about 4000 calories, well above the 2,500 to 3000 required by the average healthy male.60 Webb was fortunate; his mother and influential friends persuaded the Secretary of the Navy to discharge him on 17 December 1827.

60. Charles E Brodine, Michael Crawford and Christine Hughes: Ironsides!: The Ship, the Men and the Wars of the USS Constitution (Fireship Press, 2007), pp. 65-68.

* * * * * *

Navy Yard Philadelphia

11 September 1827 61Sir,

I have the honor to inform you that there are upwards of 100 Recruits on board the Receiving vessel at this place. And owing to the insufficiency of the Marine guard on board (consisting only of 1 corporal and 4 privates, one of whom was unfit for duty) desertions take place, and as the number of recruits increases greater desertion is to be apprehended. I this day made a request to Col Miller for a guard of 7 privates a copy of which is enclosed as also his reply and a copy of a report from Captain Hunter. If no more Marines can be furnished, I respectfully request two Midshipmen to be ordered to this station. I have the honor Sir, to be, with great Respect,

You’re obedient Servant.Wm Bainbridge

Honorable Samuel L. Southard61. Bainbridge to Southard, 10 September 1827, Letters Received by the Secretary of the Navy from Captains ("Captains Letters"), 1805-1861; 1866-85, 30 July 1827 to 6 October 1827, Volume 113, Letter number 44, RG 260, Roll 0113, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

* * * * * *

Philadelphia Oct 31, 1827 62

Honored Sir,

My situation in a great measure a distressing one compelled me respectfully to Petition you on the behalf of my son who had enlisted in the naval service. He is a young man on whom myself and family have entirely depended and without his assistance we must be reduced to a very perilous situation in the approaching winter. His name is Lyander Webb and by his industry has been able to earn from four to five hundred dollars a year. This furnished us all with comfort but in prolix of intemperance he enlisted as a seaman and has left his family who entirely depended upon him without support. By the assistance of some benevolent friends who are disposed to aid in procuring his release I shall be able to do what may be required for his discharge. I therefore pray you Sir to restore my son to his family in consideration of the circumstances.

With much respect your obedient humble servant

Eleandan Webb62. Bainbridge to Southard, 31 October 1827, p.2. Letters Received by the Secretary of the Navy from Captains ("Captains Letters"), 1805-1861; 1866-85, 6 October 1827 to 31 December1827, Volume 114, Letter number 23, RG 260, Roll 0114, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

* * * * * *

Washington

Nov 5, 1827Honorable Sir,

I have been induced to address you in behalf of a young man by the name of Lyander Webb who has enlisted in the Navy in a frolic - and now bitterly repents it. He is the sole descendent of an aged widowed mother and two young sisters, a very respectable and interesting family – who if they are deprived of his support in the coming winter will be truly miserable. I am perfectly acquainted with this young man’s character and profession – he is honest and industrious - by profession and engraver of music and musician.

Permit me therefore to entreat you to extend the hand of mercy to this truly afflicted family by orders the discharge of this deluded though good young man from his enlistment, on such terms you may deem just which will be received with sentiments of gratitude.

Sir, your respectful & obedient servant

J. Medilin[Addressed to] Samuel L. Southard, Esq.

* * * * * *

Navy Yard Philadelphia

8 November 182763Sir,

I have received your letter of the 6th instant referring a letter or Mrs. Webb to me. Lyander Webb was sent to Norfolk with the recruits recently sent from the Yard. I have shown the communication to Captain Conner, the Recruiting Officer, who assures me that no men were permitted to be enlisted in a state of intoxication and he has perfect recollection of Webb and that he was perfectly sober at the time he entered.

I have the honor Sir, to be, with great Respect,

You’re obedient Servant.Wm Bainbridge

Honorable Samuel L. Southard

Secretary of the Navy

Washington63. Bainbridge to Southard, 8 November 1827, p.1, Letters Received by the Secretary of the Navy from Captains ("Captains Letters"), 1805-1861; 1866-85, 6 October 1827 to 31 December 1827, Volume 114, Letter number 19, RG 260, Roll 0114, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

* * * * * *

Navy Yard Philadelphia

23rd June 182864Sir,

The Payroll due on the 15th instant, for the mechanics & laborers at this yard, has not been paid for want of the remittance called for by the requisition of the 4th instant; and in a few days more a second pay roll, will become due. The mechanics & laborers are in want of their pay, and it was with difficulty that we were enabled to procure the lumber we have employed for the Vandalia - which vessel I was in hopes would be ready for the 1st of August - I shall think she might be if we are not delayed for want of funds.

I respectfully beg leave to add that by my report to the Commissioners on the 20th November 1827 I estimated the following seemed then required to complete the Vandalia - for materials $34,429, for labor $32,248 to pay other appropriation’s $9,163 66/100, Total $75.52. Since then the Navy Agent has received on requisition for the Vandalia but $14,200.

I have the honor to be sir with great respect your most obedient Servant Wm. Bainbridge

[Addressed to] Honorable Thomas L Butler, Secretary of State, Washington DC.64. Bainbridge to Butler, 23 June 1828, Letters Received by the Secretary of the Navy from Captains ("Captains Letters"), 1805-1861; 1866-85, 2 June1 828 to 30 June 1828, Volume 127, Letter number 71, RG 260 , Roll 0127, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

* * * * * *

Grog Rations: Between 1800 -1830 the annual per capita consumption of alcohol increased until it exceeded five gallons - rates nearly triple that of today’s consumption.65 In this same period the navy officially served grog to sailors twice a day usually in the late morning and afternoon.66 In the early nineteenth century, drinking beer and stronger spirits in the workplace was an accepted practice and common. Grog or rum rations on U.S. Navy ships were only abolished in 1852 and all alcohol aboard naval vessels in 1914. In an age when potable water was often foul and noxious tasting, seaman and shipyard workers often preferred their libations mixed with whiskey or rum. As early as 1805, Naval Constructor Josiah Fox warned his Carpenter Quarterman and Foreman to, “[t]ake care that none of the company get intoxicated and discourage use of spirituous liquors among them during hours of work.” Supervisory personnel were further enjoined “...not to suffer any person to bring such liquor to his company unless necessity may require it.67 In 1812, the blacksmiths of the Washington Navy Yard actually sent in a formal complaint to the Secretary of the Navy stating that: “The petition of the undersigned now of the public at Washington Navy Yard respectfully represent that your petitioners conceiving themselves very much aggrieved in being deprived of the privilege of sending for necessary refreshments during their hours of work as blacksmiths, although this business is of such a nature as frequently to require that some refreshments be allowed, when the constitution is relaxed by the excessive heat or exertion.”68

65. Rorabaugh, W. J. The Alcoholic Republic: An American Tradition (Oxford University Press: New York, 1979)

8-9.66. Langley, Harold D., Social Reform in the United States Navy, 1798 -1862 (University of Illinois Press: Chicago, IL, 1967), 211.

67. Sharp, John G. M., History of the Washington Navy Yard Civilian Workforce 1799-1962 (Naval History and Heritage Command: Washington, D.C. 2005), 12-13 https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/browse-by-topic/heritage/washington-navy-yard/pdfs/WNY_History.pdf Retrieved 31 March 2019.

68. History of the Washington Navy Yard Civilian Workforce 1799-1962, p. 13.

Navy Yard Philadelphia

7th November 1828 69Sir,

Boatswain [Simon] Jordan who you ordered to the Vandalia - while attached as Boatswain to this yard was so exceedingly worthless that I had to dismiss him from the yard and recommend him for the Vandalia, thinking he might be competent to that situation but since he has been attached to the Vandalia, he has rendered scarcely any useful service and has repeatedly neglected his duty and disobeyed orders under pretension of indisposition which I believe proceeds from intemperance and which in my opinion the surgeon of the Yard joins me – although it might be difficult to prove him a drunkard - as he gets thus & no near but sufficient to signify him from being useful and I do not think him capacitated for Boatswain of a Sloop.70 I have suspended him for disobedience of orders and neglect of duty but really he is not worth the expense of a court martial. I have the honor to be Sir with great respect your most obedient Servant

[Signed] Wm. Bainbridge

Addressed to: Samuel L. Southard

Secretary of the Navy Washington69. Bainbridge to Southard, 7 November 1828, Letters Received by the Secretary of the Navy from Captains ("Captains Letters"), 1805-1861; 1866-85, 1 November1828 to 30 November 1828, Volume 132, Letter number 43, RG 260, Roll 0127, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

70. Simon Jordan (Boatswain), Born 9 October 1819, Died 10 June 1830. ne, 1830.

31 March 183271

Navy Yard Philadelphia72Sir,

In reply to your letter of the 14th instant, I beg leave to state that after the most diligent search we have not been able to find any information relative to the recruiting service on this station prior to the year 1819 from that time to the present the returns are made up and herewith transmitted, also the length of the time that the Rendezvous has been kept open during the same period - with the number and description of the vessels that have arrived and departed from this depot since 1815. I have the honor to be

Sir with great respect your obedient servantJames Barron

Honorable Levi Woodbury

Secretary of the Navy

Washington D C71. Barron to Woodbury, 31 March 1832, Letters Received by the Secretary of the Navy from Captains ("Captains Letters"), 1805-1861; 1866-85, 1 March 1832 to 31 March 1832, Volume 168, Letter number 115, RG 260, Roll 0168, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

72. Barron to Woodbury, 1 June 1832, pp 1-2, with enclosure of Dr. Thomas Harris, Letters Received by the Secretary of the Navy from Captains ("Captains Letters"), 1805-1861; 1866-85, 1 June 1832 to 31 June 1832, Volume 171, Letter number 1, RG 260, Roll 0171, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

* * * * * *

1 June 1832

Navy Yard PhiladelphiaSir,

Mr. Mark Richard, who rented the Hospital Wharf, has application for permission to pass and repass through the hospital Yard, but I find upon enquiring that indulgence would be very disagreeable to the surgeon of the Hospital, as he apprehends a variety of mischievous irregularities that would be employed by Mr. Richards.

I enclose you the copy of the letter received from the Doctor, and beg leave to request an expression of your wishes on this subject.

I have the honor to be

Sir,

Your obedient Servant

James BarronHonorable Levi Woodbury

Secretary of the Navy

Washington* * * * * *

Note: Dr. Thomas Harris was born in East Whitehead, Chester County, Pennsylvania, on 3 January 1784. His father was a Brigadier General and had served in the Revolutionary War. He attended the University of Pennsylvania in 1806, and received his medical degree in 1809. He was appointed a Naval Surgeon on 6 July 1812, and served in the War of 1812 on the USS Wasp as surgeon.

On the morning of 18 October, USS Wasp and HMS Frolic closed to do battle. The engagement would be the first and only time Wasp saw combat. The two ships commenced fire at a distance of 50 to 60 yards (46 to 55 m). In a short, sharp fight, both ships sustained heavy damage to masts and rigging, but Wasp prevailed over her adversary by boarding her. The HMS Frolic suffered 15 killed in action and 43 wounded. The Wasp suffered five men killed in action and five wounded.73 Dr. Harris and the British surgeon worked together to amputate wounds and staunch bleeding. Later in 1820, Dr. Harris was presented with a Congressional Medal for his courage and heroic service under fire. The victory was short-lived, however. Unfortunately for Wasp, a British 74-gun ship-of-the-line, HMS Poitiers, appeared on the scene. Frolic was crippled and Wasp's rigging and sails were badly damaged. At 4:00 PM, Jones had no choice but to surrender Wasp; he could neither run nor fight such an overwhelming opponent. Dr. Harris was taken to Bermuda as a Prisoner of War, but was released on parole.

In 1815, Dr. Harris was surgeon on the USS Macedonia, which along with the USS Constellation and USS Guerrier, was sent to the Mediterranean under Commodore Stephen Decatur to suppress Algerian privacy. In a fight with the Algerian flagship Mashuda, four American sailors were killed in action and ten wounded. Dr. Harris provided medical care to the wounded in both vessels and stayed on the Mashuda to treat the large number of Algerian wounded. After the war, Dr. Harris was ordered to Philadelphia, serving the Philadelphia Navy Yard, the Naval Rendezvous and the Philadelphia Naval Asylum.73. James, William, Naval Occurrences of the War of 1812: A full and Correct Account of the Naval War Between Great Britain and the United States, 1812-1815, Introduction, Andrew Lambert, (T. Egerton, London, 1817), reprinted (Conway Maritime Press, London, 2004), pp. 73-74.

The Court Martial of Dr. William Barton: In 1818, Dr. William Barton was tried by court martial for attempting the removal of a fellow naval physician, Dr. Thomas Harris. This case was settled on February 11, 1818, when Barton was found guilty. Dr. Harris wrote, “During the war, I attended to the duties assigned to me by the government without intermission of a day while Barton absented himself from duty and declined the order to join our vessel when on the eve of sail and were in need of surgeon.”74

74. Roddis, Louis H. “Thomas Harris, M.D., Naval Surgeon and Founder of the First School of Naval Medicine in the New World.” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, vol. 5, no. 3, Oxford University Press, 1950, pp. 236–50, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24620018

The case stemmed from Dr. Barton allegedly accusing Dr. Harris, then Director of the Philadelphia U.S. Naval Hospital, of allowing overcrowded and unsanitary conditions to prevail in that institution and of soliciting Harris' removal. At the end of the trial, Dr. Barton was admonished, but he was acquitted of a "willful and deliberate falsehood."75 The Barton court martial became a precedent, as President James Monroe was called to give testimony.

75. Stathis, Stephen W. “Dr. Barton's Case and the Monroe Precedent of 1818,” The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 32, No. 3 (Jul. 1975), pp. 465-474.

In 1832, Harris operated on President Andrew Jackson and he successfully extracted a bullet lodged in the President’s body for twenty-six years. The bullet was the result of a duel Jackson had fought twenty-six years previously.

On 1 April 1844, Dr. Harris was appointed Chief of the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery.

Thomas Harris 1874-1861

The Second Chief of the Bureau of Medicine & SurgeryNavy Yard Philadelphia

31st May 183276Sir,

The persons who have rented the wharf at the Asylum require permission to cross the lot with carts and wagons. I have refused to deliver the keys until you give the order to that effect.

When the lot was rented, I presume it was the intention of the Commissioners that it should be used merely as a place of deposit. If permission is given to them to cart the stone, coal, wood, &c through this property, it will, I am sure, sustain an injury double or treble the whole amount of the rent. Drunken & reckless carters will disregard fences, grass, fit and ornamental trees, and everything which is calculated to give security & value to the estate. The gates will be unavoidably left open and strange cattle will be constantly pasturing on our fields and breaking our trees. This might be partially guarded against by erecting new fences, and by making a lane from the Gray’s Ferry road to the river. These fences would cost more than the year's rent. They could be of no permanent advantage, however, and would greatly disfigure the lot. I hope you will refuse this permission to cross the lot, as I am persuaded the Commissioners never intended to grant privileges which would so seriously injure the beauty of the property.I have the honor to be very respectfully

[Signed] Thomas Harris 77, 78

Addressed to Commodore J. Barron

Commandant Naval Station PhiladelphiaNote: On the reverse, Secretary of the Navy Levi Woodbury noted

“Permission cannot be granted unless Mr. B will permit”76. Barron to Woodbury, 1 January1833, Letters Received by the Secretary of the Navy from Captains ("Captains Letters"), 1805-1861; 1866-85, 1 Jan 1833 to 31 Jan 1833, Letter number 29, p.1, with enclosure, RG 260, Roll 0178, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

77. Thomas Harris, Surgeon, born 6 July, 1812, died 5 March, 1861.

78. School of Naval Medicine in the New World.” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, vol. 5, no. 3, Oxford University Press, 1950, pp. 236–50, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24620018

* * * * * *

Navy Yard Philadelphia

2nd June 183279Sir,

Herewith I enclose a letter from Doctor Barton, Surgeon of the Navy Yard which sets forth the necessity under which he labors, for the want of a proper person to attend him as a man, nurse or Loblolly Boy.80 I have frequently remarked the justice of his wishes on this subject, such a person as he requires to take proper care of the sick, medicine and surgical instruments cannot be selected from the ordinary of the yard, or the crew of the receiving vessel, [USS Seagull] and if a suitable one is not put at his command keep these valuable articles in such a state of preservation, as the interest of the service requires.

I would therefore most respectfully, beg leave to suggest, and also recommend that such an assistant be allowed either in the character of a Seaman, Ordinary Seaman or laborer; the latter would be preferred. I would not most assuredly trouble you with a communication of such a trifling import, were I not convinced that this indulgence of the Doctor’s wishes will contribute to the good of the service here, and comfort of the sick. I have the honor to be very respectfully

Your obedient servant James BarronTo: Honorable Levi Woodbury

Secretary of the Navy,

WashingtonNote on reverse, by Secretary of the Navy Levi Woodbury,

“The duties of the “Loblolly Man” to the Surgeon, and the re-enter to allow him to live with his family out of the Navy Yard, near thereto, is fully within the competence of the Commander of the Yard. W”

79. Barron to Woodbury, 1 June 1832, with enclosure of Dr. Barton, pp. 1-2, Letters Received by the Secretary of the Navy from Captains ("Captains Letters"), 1805-1861; 1866-85, 1 June 1832 to 31 June 1832, Volume 171, Letter number 6, RG 260, Roll 0171, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

80. Loblolly boy is the informal name given to the assistants to a ship's surgeon aboard British and American warships during the Age of Sail. The name derives from a porridge traditionally served to sick or injured crew members. The name was first used to describe Royal Navy surgeon's assistants in 1597. The rating was also used in U.S. Navy warships from the late 18th century until 1861, when the name "surgeon's steward" was introduced to reflect more stringent training requirements. The name was changed to apothecary in 1866, and again in the 1870s to bayman and then in the early 20th century to Hospital Corpsman. The Royal Navy name changed to sick berth attendant. in 1833, with the nickname "Sick Bay Tiffy" (Tiffy being slang for artificer) gaining popularity in the 1890s. Medical Assistant is the current term. The loblolly boy's duties included serving food to the sick, but also undertaking any medical tasks that the surgeon was too busy (or too high in station) to perform. These included restraining patients during surgery, obtaining and cleaning surgical instruments, disposing of amputated limbs, and emptying and cleaning toilet utensils. The loblolly boy also often managed stocks of herbs, medicines and medical supplies.

* * * * * *

Dr. William Paul Crillon Barton, USN

Liriodendron Tulipifera, William BartonNote: In the following letter, Dr. William Paul Crillon Barton (November 17, 1786 to March 27, 1856) writes to Commodore Barron requesting Ordinary Seaman, Frederick Wacker as a loblolly boy or nurse assistant at the Philadelphia Naval Hospital. The two men had served together aboard the USS Java.81 The name Loblolly Boy derives from porridge traditionally served to sick or injured crew members. The rating of Loblolly Boy was used in U.S. Navy warships from the late 18th century until 1861. Frederick Wacker was a German immigrant, who arrived in the United States about 1810. He first worked as a merchant seaman and later joined the Navy. Wacker took out Seamen’s Protection Papers on 28 August 1823.82

IMAGE: Frederick Wacker Seaman’s Protection Certificate 28 Aug 1823

81. Miscellaneous Records of the Navy Department, Muster Rolls, USS Java 1827-1828, p. 31, no. Frederick Wacker, Ordinary Seaman.

82. The National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., Proofs of Citizenship Used to Apply for Seamen's Certificates for the Port of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1792-1885, Frederick Wacker, 28 August 1823.

Dr. William Barton was a renowned medical botanist, physician, professor, naval surgeon and botanical illustrator. Barton was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on 17 November 1786. He studied classics at Princeton University and received his BA in 1805. He later took a degree in medicine from the University of Pennsylvania Medical School under his uncle William Smith Barton, a noted botanist and the author of the first American textbook on botany. Dr. Barton retained a keen interest in botanical and herbal science throughout his life. Following medical school, he was commissioned a naval surgeon on 28 June 1809. Barton fought to tighten the controls of shipboard medical supplies. He called for the introduction of lemons and limes aboard Navy ships long before the U.S. Navy accepted the importance of an antiscorbutic treatment for vitamin C deficiency or scurvy. Barton went as far as to send a bottle of lime juice to the Secretary of the Navy, Paul Hamilton, with the instructions to drink it in the form of lemonade.

In February 1811, Congress passed an act establishing naval hospitals. Secretary of the Navy, Paul Hamilton, later asked Barton to compose a set of regulations for governing these hospitals. Barton was well aware of the shortcomings in Navy medical care. Shipboard facilities were primitive, and there were no permanent hospitals ashore, only temporary facilities in Navy yards.

Barton began by drafting rules for governing naval hospitals. In 1812, the Navy Department submitted them to Congress. "Each hospital accommodating at least one hundred men should maintain a staff including a surgeon, who must be a college or university graduate; two surgeon's mates; a steward; a matron; a ward master; four permanent nurses and a variety of servants." Not satisfied with the hastily drafted suggestions, Barton expanded his theories in a treatise published in 1814.8383. Capt. Frank L. Pleadwell, "Edward Cutbush, M.D.: The Nestor of the Medical Corps of the Navy." Annals of Medical History 5 (1923): p. 267.

Dr. Barton has been described as the first to promote the idea of employing female nurses in the U.S. Navy. He wrote the "matron's characteristics: she should be discreet ... reputable ... capable ... neat, cleanly, and tidy in her dress, and urbane and tender in her deportment… She would supervise the nurses and other attendants as well as those working in the laundry, larder, and kitchen, but her main function was to ensure that patients were clean, well-fed, and comfortable."84 Here Dr. Barton was advocating the employment of white women, as black women, as he well knew, were already working in naval hospitals as nurses, washers and cooks.85

84. Holcomb, Richard C., A Century with Norfolk Naval Hospital (Printcraft Publishing: Norfolk 1930), 166.

85. Sharp, John G. M., Gosport Naval Hospital Staff 1834.

http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/nnysharp10.htmlThe Court Martial of Dr. William Barton: In 1818 Dr. Barton was tried by court martial for attempting the removal of a fellow naval physician Dr. Thomas Harris. This case was settled on February 11, 1818, when Barton was found guilty. The case stemmed from Dr. Barton allegedly accusing Dr. Harris, then Director of the Philadelphia U.S. Naval Hospital, of allowing overcrowded and unsanitary conditions to prevail in that institution and of soliciting Harris' removal. Barton, though, was acquitted of a "willful and deliberate falsehood.86 The case was also a precedent as President James Monroe was called to give testimony. While Dr. Barton was admonished, his career did not suffer.

86. Stathis, Stephen W. “Dr. Barton's Case and the Monroe Precedent of 1818” The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 32, No. 3 (Jul., 1975), pp. 465-474.

Botanicals: Barton’s Vegetable materia medica of the United States, or Medical botany (1817-1818), was published early in his career. This work established Dr. Barton’s standing as an experienced professional, able to distinguish between myth and fact about many American native plants.87In 1823, Dr. Barton wrote and illustrated (see illustration above) his important Flora of North America. Barton's Flora is an important early American color plate book. Like many other illustrated works of science and natural history of this period, the rich illustrations of Barton’s Flora made the publication expensive to produce. To offset the cost, it was sold by subscription. Subscribers would have bought the book ready-made. Instead, they received installments of one or two sections at a time and had their copies bound as the volumes were completed.

87. Valauskas, Edward J., William Barton: Reputation and Botany in Early America, Chicago Botanic Garden Lenhard Library 2015 https://library.missouri.edu/news/special-collections/a-flora-of-north-america-by-william-p-c-barton accessed 15 June 2019

* * * * * *

1 June 1832

Sir,