Commodore Joshua Barney and the Naval Flotilla

at the Battle of Bladensburg 24 August 1814

BY

JOHN G. M. SHARP

The Battle of Bladensburg, fought on 24 August 1814, was one of the worst days in American military history. As historian Daniel Walker Howe has noted, "The verdict of history terms Bladensburg the greatest disgrace ever dealt to American arms."1 The rout that day of the ill trained and poorly led American army and militia resulted in the quick capture of the national Capitol and the burning of the White House.2 Shortly afterward, Baltimore newspaper editor Hezekiah Niles derided the militiamen who "generally fled without firing a gun, and threw off every encumbrance of their speed!" while an anonymous 1816 ballad, "The Bladensburg Races" satirized the battle and cast President James Madison as the retreater-in-chief..."3 Nevertheless, a few units and individuals performed heroic service. Notable among the latter was the Naval Flotilla and its leader Commodore Joshua Barney. At Bladensburg the Flotilla would fight as infantry. At this crucial battle they were composed of about 500 sailors plus 120 marines under Captain Samuel Miller. Yet together they inflicted the bulk of British casualties and were the only effective American resistance during the battle.4, 5 This is article relates the story of the Commodore Barney and the Naval Flotilla at the Battleof Bladensburg.

1. Howe, Daniel Walker, What Hath God Wrought The Transformation of America, 1815 to 1848 (Oxford University Press, New York, 2007), p. 64.

2. Wood, Gordon S, Empire of Liberty A History of the Early Republic, 1789 to 1815 ( Oxford University Press, New York), p. 691.3. Sneff, Emily, Spooked Horse or Spooked President, John Gilpin, James Madison, and The Bladensburg Races https://ageofrevolutions.com/2021/06/14/spooked-horse-or-spooked-president-john-gilpin-james-madison-and-the-bladensburg-races/

4. Dudley, Donald, "Joshua Barney Perseverance and Resourcefulness" Leadership Embodied: The Secrets to Success of the Most Effective Navy and Marine Corps Leaders, editor Joseph J. Thomas (Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland, 2013), 2013, pp. 11-15.

5. Shomette, Donald G., Flotilla The Patuxent Naval Campaign in the War of 1812 (John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 2009), p. 257.

Final Stand at Bladensburg, Maryland 24 August 1814

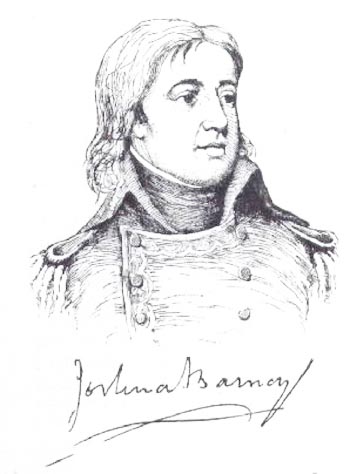

Marine Corps Art CollectionCommodore Joshua Barney

The leader of the Naval Flotilla, Commodore Joshua Barney, was born on 6 July 1759 near Baltimore, Maryland, into a prosperous upper middleclass family. He was one of fourteen children. Both his father William and mother Francis Watts owned large landholdings worked by numerous enslaved men, women and children. From early on Barney disdained a quiet life and instead went to sea at age twelve. He served in merchant ships before the American Revolution and later became an officer in the Continental Navy. There he served in the sloops Hornet and Wasp and subsequently sailed on privateers. During the Revolution he was captured by the British twice and twice escaped confinement as a prisoner of war in England.6 Throughout his lifetime Barney was a slaveholder, with much of his wealth based on the enslaved working his fields.7 In the 1790’s he purchased an old brigantine the Liberty that transported men, women and children as cargo from Baltimore to Cartagena, Columbia.8, 9, 10, 11 At one point he seriously considered becoming a plantation owner at Cape François, Haiti.12 As the American abolitionist movement grew, Barney’s large investment in the international slave trade would follow him as he unsuccessfully ran for political office.6. Norton, Arthur Louis, Joshua Barney Hero of the Revolution and 1812 (Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, 2000),pp. 2-3

7. A Biographical Memoir of the Late Commodore Joshua Barney from Autobiographical Notes and Journals edited by Mary Barney (Grey and Bowen, Boston, 1832), p. 298.

https://openlibrary.org/works/OL201868W/A_biographical_memoir_of_the_late_Commodore_Joshua_Barney8. Norton, pp. 109-111.

9. The Star Spangled Banner, National Historical Trail, Joshua Barney, National Parks Service, https://www.nps.gov/stsp/learn/historyculture/joshua-barney.htm

10. Commodore Joshua Barney House (Harry's Lott), Maryland Historical Trust https://mht.maryland.gov/secure/medusa/PDF/Howard/HO-41.pdf

11. Langley, Harold D., Journal of the Early Republic, vol. 21, no. 2, 2001, pp. 353–55. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3125223 accessed 19 Jul 2022.

12. A Biographical Memoir of the Late Commodore Joshua Barney, p. 205.

At the outbreak of the War of 1812, Barney commanded the Baltimore schooner Rossie, in which he captured the British Post Office packet ship Princess Amelia. During the engagement the Princess Amelia had to strike after she had lost three men killed, including her captain, and her sailing master, and 11 men wounded.12a

12a. Norway, A.H., History of the Post-office Packet Service between the Years 1793-1815 (Macmillan and Company, New York, 1895), pp. 226-227.

While employed as a privateer captain, Barney was a success and profited greatly, his profit from his ninety day voyage on the Rossie amounted to $18,195.12bThat same year Joshua Barney entered the US Navy as a captain.

12b. Norton, p. 166.

Chesapeake Naval Flotilla

On 4 July 1813 Joshua Barney submitted a plan for the defense of the Chesapeake Bay to Secretary of the Navy, William Jones, in which he detailed a bold plan to harass and annoy the larger British vessels.1313. The Naval War of 1812, A Documentary History, Volume II, Editor William S. Dudley, (Naval Historical Center, Government Printing Office Washington D.C., 1992),pp373-376 https://books.google.com/books?id=fxt3AAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=The+Naval+War+of+ 1812+A+Documentary++History,+Volume+II+edited+by+William+S.+Dudley&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_ redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj81oTyjI_5AhWioWoFHUNqA8oQ6AF6BAgGEAI#v=onepage&q=barney&f=false

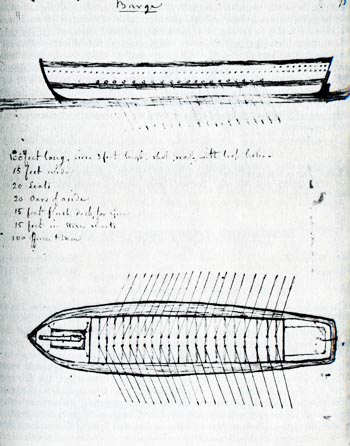

The Avowed object of the enemy is the destruction of the City & the Navy Yard at Washington, the City and the Navy Yard at Norfolk and the city of Baltimore … I am therefore of opinion the only defense we have in our power, is a Kind of Barge or Row-galley, so constructed, as to draw a small draft of water, to carry Oars, light sails, and One heavy long gun . . . Let as many of such Barges be built as can be manned, form them into a flying Squadron, have them continually watching & annoying the enemy in our waters, where we have the advantage of shoals & flats throughout the Chesapeake [sic] Bay . . . and the enemy dare not dispatch Small ships, brigs, or Schooners upon any expedition whilst such a force lay near them.14, 15

14. Joshua Barney to William Jones, re Defense of the Chesapeake Bay, July 4, 1813. Manuscript/Mixed Material, Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/item/mjm017001/

15. Shomette, p. 429, n29.

Barney estimated that a force consisting of gunboats and barges that could be sailed or rowed, manned by sailors and those in the shipbuilding industries, could engage British landing parties in the shallow waters of the Bay. He set sail in April 1814 with these eighteen ships: seven 75-foot (23 m) barges, six 50-foot (15 m) barges, two gunboats, one row-galley, one lookout boat and his flagship, the 49-foot (15 m) sloop-rigged, self-propelled floating battery USS Scorpion, mounting two long guns and two carronades.

Secretary of the Navy, William Jones, accepted Barney’s plan and offered him the rank of acting master commandant and made the new Flotilla command answerable only to him.

While Barney’s force on paper totaled 4,370 men, the harsh reality of war meant the Flotilla was constantly plagued by desertion, illnesses and casualties. They were in fact something of a motley crew, composed of U.S. Navy sailors, seamen, and Chesapeake Bay watermen. In addition careful research by Donald G. Shomette has revealed the Flotilla had a significant component free and some enslaved blacks.16 Later, when they became shipless and on the march from Benedict, Maryland, marines from the Washington Navy Yard would join them, as they moved north to defend the Capital and make an abortive stand at Bladensburg against the rapid British advance.

16. Shomette, p. 429, n29.

Barney's men with two 18-pounder guns and three 12-pounder guns drawn from the Washington Navy Yard were posted astride the Washington turnpike. Prior to Bladensburg tThe Flotilla engaged the Royal Navy in several inconclusive battles at St. Jerome Creek , St. Leonard's Creek and Queen Anne all of which left The British, frustrated by their inability to destroy the Flotilla or capture Barney. Following the Battle of Queen Ann, Barney was forced to scuttle his vessels and march to Bladensburg. The men of the Flotilla then served onshore in the defense of Washington, DC and Baltimore. The Flotilla was disbanded on the conclusion of the war on February 15, 1815.

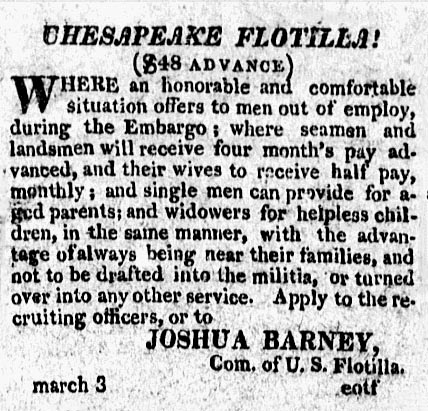

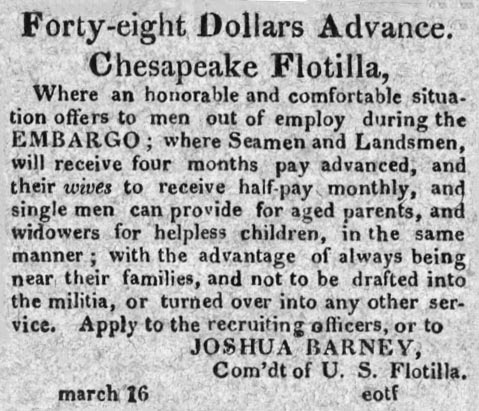

Recruitment

During the war Commodore Barney‘s new "Chesapeake Flotilla" had to compete with the Army, the Marine Corps and other U.S. naval ships and units for recruits. Barney did this by offering a substantial advance $48 to those willing to enlist. In charge of recruitment for the Flotilla was Lieutenant Solomon Frazier. Barney wrote Frazier is a "well-known Character, perhaps the most popular among the seafaring men on the Eastern Shore, of any man in Maryland."17 Frazier was a Maryland State Senator and who, like Barney. had seen active and indeed heroic service during the Revolutionary War. Although rich and at his ease, Frazier was willing to serve under Barney.18 As a Flotilla Division Commander, Frazier became an important attribute.1917. Ironsides! The Ship, the Men and the Wars of the USS Constitution, Brodine, Charles E., Crawford, Michael J. and Hughes, Christine F. (Fireship Press, 2007), p. 47.

18. Shomette, p. 57.

19. On May 4, 1813, Captain Solomon Rutter was ordered to place a chain-mast boom across the northwest channel. See Remembering Baltimore, 28 Nov 2018, http://www.rememberingbaltimore.net/2018/11/1814-defending-baltimore.html

Barney’s second in command was Lt. Solomon Rutter who was appointed on 15 September 1813. Rutter had previous experience in command and had recently been responsible for laying a boom to impede the main channel approach to Baltimore harbor and had commanded a unit of Marine artillery.20, 21 Lt. Rutter would later play an important role in the Defense of Baltimore.22 Despite Barney and Frazier’s best efforts, recruitment for the Flotilla lagged. As one distinguished historian has written the idea military service was met with indifference and even distain in many of the middle and northern states. "Undoubtedly the War of 1812 was the most unpopular war this country has ever waged excepting the Viet Nam War."23

20. Dudley, William S. pp. 222-223.

21. Morison, Samuel Eliot. "Our Most Unpopular War." Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, vol. 80, 1968, pp. 38-166, JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25080655 accessed 11 Aug. 2022.

22. Shomette, p. 338.

23. Morison, Samuel Eliot. "Our Most Unpopular War" Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, vol. 80, 1968, pp. 38-166, JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25080655 accessed 11 Aug. 2022.

Battle of Bladensburg 24 August 1814

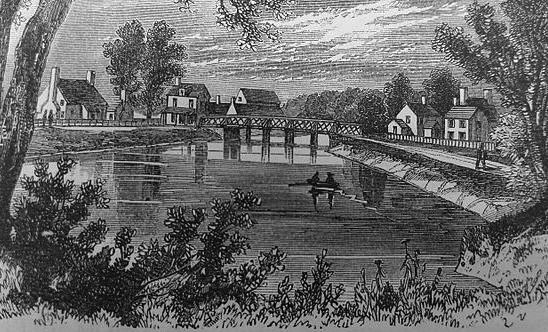

Commodore Barney’s Flotilla and a company of Marines were originally delegated to blow up the bridge nearest the navy yard when the enemy approached. Barney instead persuaded the James Madison’s cabinet to detail a smaller force for this task, thus permitting his men to join the army and militia at Bladensburg. By early morning on the 24th General Winder had dispatched a note to Joshua Barney directing him to move his men and artillery to take command of the defense of the lower bridge where other militia units were already posted.On the morning of August 24, 1814, as Commodore Barney and the flotilla waited by road leading to the Bladensburg Bridge, the heat and humidity in the tidewater country were raising.

The British troops arriving at Bladensburg were ill prepared for summer in their heavy woolen red coats and already exhausted from their long march from Benedict, Maryland. Some of the King's soldiers had already become stragglers and fallen out. "These were the dog days of summer, with the temperature reported at 100˚F during the thick of battle of the coming battle." British Lt. George Gleig recalled,

We had now proceeded about nine miles, during the last four of which the sun’s rays had beat continually upon us, and we had inhaled almost as great a quantity of dust as of air. Numbers of men had already fallen to the rear, and many more could with difficulty keep up consequently, if we pushed on much farther without resting, the chances were at least even one-half of the army would be left behind. … [After a small rest] by the banks of the wayside were again covered with stragglers; some of the finest and stoutest men in the army being literally unable to go on.24

24. Gleig, George R. The Campaigns of the British Army at Washington and New Orleans 1814 - 1815 (Milton Keyes, Leonur, 2007) reprint of 1827 edition) p. 49.

That morning Brigadier General William H. Winder who was charged with blocking the British advance had posted his troops on the high ground along the western banks of the Anacostia River. Winder was a not a military man but instead a well-connected politician and lawyer. His only substantial previous military experience had resulted in his capture at the battle of Stoney Creek in 1813. He was exchanged in 1814 and appointed by President James Madison (possibly because he was nephew of Levin Winder, Federalist Governor of Maryland) to the vital 10th military district which encompassed Baltimore and the Washington, DC, the national capital.

Winder could call in theory upon 15,000 militia but he actually had only 120 dragoons and 300 other regulars, plus 1,500 poorly trained and under-equipped militiamen at his immediate disposal.25 Benjamin Henry Latrobe who oversaw the construction of the United States Capitol and knew men and officers of the local militia well, wrote about the Detachment of Navy Yard Rifles (volunteers), commanded by Captain John Doughty, and he was not impressed. Latrobe found the Navy Yard Rifle Company (later named Stull's Rifle Company), like most militia companies, had more enthusiasm than military skill.26 He wrote,

Upon the whole I find that the Navy Yard cannot produce a single good rifleman. But if there is more than one to be found, no one knows better than you that, to acquire competent skill as a marksman much leisure devoted to constant practice, is necessary. This leisure the mechanics of the Navy Yard can only obtain, by sacrifice of their time and pay, a sacrifice which they neither can, nor will make.27

25. Taylor, Allan, The Internal Enemy Slavery and War in Virginia, 1772 -1832 (WW Norton, New York, 2013), pp. 300 -301.

26. Todd, Frederick P., "The Militia and Volunteers of the District of Columbia 1783-1820", Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C., Vol. 50 (1948/1950), pp. 379-439), JSTOR https://www.jstor.org/stable/40067335?read-now=1&refreqid=excelsior%3A66cf6c62309bc9c17a4fc28d03ed42ec&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

27. Papers of Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Volume II, Editor Edward C. Carter II (New Haven, Yale University Press, 1984-1988), pp. 453-454.

As the battle opened, the Maryland and District militia quickly panicked, aided by a rumor which had spread among the troops of a slave insurrection. In part this was because white militia units had seen the British Colonial Marines former slaves and took them for slaves in armed rebellion.28, 29 One of the American militia officers who witnessed it was Francis Scott Key, hence the third verse of the anthem now rarely sung, "No refuge could save the hireling and slave from the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave."

28. Gleig, p. 92.

29. The London Gazette, 27 September 1814. pp. 1942–1943.

During the battle the young enslaved Michael Shiner, was nine years of age. He was living in Washington D.C. at the house of slaveholder William Pumphrey on Grant Row, which now is in on East Capitol Street, where he learned news of the battle and heard the cannon fire. While unimpressed by the militia whom he saw in retreat, Shiner later wrote of Commodore Barney and the Flotilla,

We heard a roar cannonading and Military and that time Commodore Barney had placed himself in a position which where was spring which to this day is called Barney’s spring. Then the orders where given for the American army to retreat and at that this time they were in confusion and fled in every direction still Commodore Barney held his positon When the British columns were ordered to advance across Bladensburg Bridge were met with grape and canister for Commodore Barney ordered a shower of balls from the Marines as fast as the columns would advance. 30

30. Shiner, Diary, 1814, p. 5.

In 1835 Shiner recorded seeing the District Militia they were a great turn out of the Merlicia [Militia] in Washington on the 27 day of June 1835 on Saturday they were Ragedis white people that ever I saw in my life and they uniforms was of old rags and them that were officer they epaulets wore were cows hoofs and they had Drums and fifes and they had clarinets their Drums were composed of old tin pans and old pots and all kinds of old sheet iron and they flutes clarinets and fifes and bugles where composed of Rams horn and oyster horns. Shiner Diary 1835, p. 57.

During the battle the Chesapeake Flotilla, with only its armed seamen and 120 Marines, stood their ground and the British suffered heavy casualties at the hands of Barney's cannoneers.

Again and again the Flotilla sailors and Marines repulsed the troops who attacked them in front. After half an hour they were outflanked. The last act of the battle was fought at close quarters with bayonets, pistols and swords. In the final desperate moments of the clash, two young sailors, George Gallagher and Henry "Harry" Jones, who as Boys who were carrying gun powder to the Flotilla cannons, when they were badly wounded. Young Henry Jones would spend over a month at Naval Hospital, Washington Navy Yard; he was later discharged 3 December 1814.34 George Gallagher, though was in far worse condition, for he had been hit in the leg so badly as to require amputation on the scene. Gallagher spent two months at Naval Hospital, Washington Navy Yard. He was later listed as discharged on 24 March 1815 with the notation, "lost in action."35 At about the same time Commodore Barney was shot in the thigh, a wound that would trouble him for the rest of his life. Captain Samuel Miller was shot in the arm. Recognizing the Maryland and District militia had run and that the Flotilla was flanked, Barney gave the order for his men to withdraw. Despite pleas from his subordinates he ordered his staff to leave him.

34. Shomette, p. 367, entry 134.

35. Shomette, p. 367, entry 132.

The final desperate Marine counterattack was simply not enough; Barney and Miller’s forces were overrun. In all, out of the total of 114 Marines, 11 were killed and 16 wounded. Most of those listed in the register as wounded at Bladensburg probably suffered shrapnel or gunshot in this climatic moment of battle. British Admiral Sir George Cockburn later on surveying the field, complemented Barney for his courage, paroled him and bought him into Bladensburg for medical care on a litter. Captain Samuel Miller whose arm was badly wounded was quickly paroled and brought to the naval hospital for treatment where he remained from August 28, 1814, to September 9, 1814. Most of the Flotilla escaped captivity and would take their places at the Battle of Baltimore to man the cannons on September 12-15, 1814.

Both Commodore Barney and Captain Samuel Miller were found together with the guns. One of the British officers, writing afterwards, spoke with the utmost admiration of Barney's men.

"Not only did they serve their guns with a quickness and precision that astonished their assailants, but they stood till some of them were actually bayoneted with fuses in their hands; nor was it till their leader was wounded and taken and they saw themselves deserted on all sides by the soldiers, that they left the field."

Memorial to the Battle of Bladensburg

designed and sculpted by Joanna Blake 201Black sailors are absent in many historical narratives of the battle, and pictorial representations including the well-known oil "The Final Stand at Bladensburg" by Colonel Charles Waterhouse USMCR. However, time and a new generation of historians have broadened our understanding of the battle and the men who fought there. In 2014 on the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Bladensburg, a new memorial sculpture was unveiled. The "Undaunted in Battle" memorial designed and sculpted by Joanna Blake depicts a wounded Commodore Joshua Barney, commander of the Chesapeake Flotilla, Charles Ball, a freed slave and flotilla man, and an unnamed Marine, in honor of the Marines who fought to the bitter end trying to repel British forces.36Most scholars of the War of 1812 today agree the Chesapeake Flotilla was composed of a number of free and enslaved blacks but are unable to provide an exact number.37

36. Naval History News, June 2014, Volume 26, Number 3, U.S. Naval Institute, https://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/2014/june/naval-history-news

37. Shomette, pp. 58, 429 n29.

Part of the difficulty resides in the early U.S. Naval musters and payroll records which, with few exceptions, contain no racial or ethnic identity of the men and boys who made up the Naval Flotilla. More specificall, the muster and payroll records of the Naval Flotilla were by Commodore Barney’s own admission a mess. Writing to Secretary of the Navy Jones on 29 October 1814, the Commodore blamed his purser John S. Skinner.38

I have never been able to obtain from him [Skinner] a simple muster book, and although continually demanding one from him, I know how many men I have, yet I do not know when the men entered, when dead, when discharged, when run, or, in fact, a single circumstances which his duty directs him to do – he is never present

38. Joshua Barney to William Jones, 29 Oct 1814, Letters Received by the Secretary of the Navy from Captains, ("Captains Letters"), 1805-61; 1866-85, volume 40, letter 76, Roll, 0040, pp. 1-3, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC.

Early naval regulations actively discouraged the recruitment of African Americans, free or enslaved. An 1798 order from the Secretary of the Navy, Benjamin Stoddard, is typical of the era. "No Negroes or Mulatoes are to be admitted, and as far as you can judge, you must be cautious to exclude all Person whose Characters are suspicious."39 This and similar proclamations made earlier by the Secretary of War in March of the same year would serve to bar Blacks from enlisting in the Marine Corps and the Army. Nevertheless, due to extreme manpower shortages, on 3 March 1813 the Department of the Navy reversed the ban and allowed free African Americans sailors in the fleet, allowing for "persons of color" to serve on "public vessels" of the United States.

39. Secretary of the Navy, Benjamin Stoddard to Lt. Henry Kenyon, 8 August 1798, Naval Documents Related to the Quasi-War Between the United States and France, Washington, 1935, Vol.I, p. 281.

Recent scholarship has found that during the War 1812 the African American Naval participation represented one-sixth of naval personnel in this conflict.40 While enslaved Blacks remained officially barred by the Navy from enlistment, the practice continued throughout the War of 1812.41 Military policies regarding enslaved labor were haphazard, more a mix of differing plans and ideas than a coherent program. During and after the War of 1812, the Department of the Navy continued to utilize enslaved labor.42

40. African American Sailors in the U.S. Navy A Chronology, Naval History and Heritage Command

https://www.history.navy.mil/browse-by-topic/diversity/african-americans/chronology.html41. The Diary of Michael Shiner Relating to the History of the Washington Navy Yard, editor John G. Sharp Naval History and Heritage Command, 2015, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/d/diary-of-michael-shiner/introduction.html

42. Nathaniel Haraden to Board of Navy Commissioners 11 May 1815, NARA RG45 E307 v. 1.

Charles Ball, an enslaved man who had formerly worked in the Washington Navy Yard, served aboard the USS Congress and later enlisted in the Naval Flotilla.43 Ball enlisted in December 1813 and served as a seaman and cook and was discharged in the fall of 1814. He marched with Barney‘s troops from Benedict to Bladensburg and worked the cannon to the left of Barney until the Commodore was shot down.44

43. Slavery in the United States: A Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Charles Ball, a Black Man, Who Lived Forty Years in Maryland, South Carolina and Georgia, as a Slave Under Various Masters, and was One Year in the Navy with Commodore Barney, During the Late War (New York: John S. Taylor, 1837), pp. 21, 403.

44. Grulich, Anne Dowling, Putting Charles Ball on the Map in Calvert County, Maryland, 2014, pp. 6-7, University of Maryland, https://jefpat.maryland.gov/Documents/mac-lab/grulich-anne-dowling-putting-charles-ball-on-the-map-in-calvert-county-maryland.pdfBall’s account of the Battle of Bladensburg is extremely valuable to historians for it provides detail on how an observant black sailor experienced the conflict.

When we reached Bladensburg and the flotilla men were drawn up in line to work at their cannon, armed with their cutlasses, I volunteered to assist in working the cannon that occupied the first place on the left of the Commodore. We had a full and perfect view of the British army, as it advanced along the road, leading to the bridge over the East Branch; and I could not but admire the handsome manner in which the British officers led on their fatigued and worn-out soldiers. I thought then, and think yet, that General Ross was one of the finest looking men that I ever saw on horseback. I stood at my gun, until the Commodore was shot down, when he ordered us to retreat, as I was told by the officer who commanded our gun. If the militia regiments, that lay upon our right and left, could have been brought to charge the British in close fight as they crossed the bridge, we should have killed or taken the whole of them in a short time, but the militia ran like sheep chased by dogs.45

45. Ball, Slavery in the United States: p. 404.

After the war Charles Ball, was recaptured by a slaveholder. He later recollected his disappointment and regret, a regret that many African American who served their country in the war of 1812 must have shared.

The thought now struck me, that if I had deserted that day and gone over to the enemies of the United States, how different would my situation at this moment have been. And this, thought I, is the reward of the part I bore in the dangers and fatigues of that disastrous battle.

Source: Ball, pp 482-483

We know Commodore Barney’s group included numerous African Americans as part of the Naval Flotilla. One observer by President James Madison's side as he reviewed Commodore Barney's Naval Flotilla was Madison's young enslaved "servant" Paul Jennings (1799-1874). Jennings later wrote, "A large part of his men were tall, strapping Negroes, mixed with white sailors and marines. support during the battle. When Madison asked Barney "if his negroes would not run on the approach of the British?" he replied, "No Sir…they don’t know how to run; they will die by their guns first."46

46. Jennings, Paul, A Colored Man's Reminiscences of James Madison (Brooklyn, New York: George C. Beadle, 1865), pp. 7-8. https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/jennings/jennings.html

Examples of Chesapeake Flotilla Black Sailors

(click underlined to open links)Henry "Harry" Jones, Boy, #134, p.6, Chesapeake Flotilla, payroll, p 2. First page reads, "Payroll of the Officers, Seamen &c attached to the Chesapeake Flotilla, Joshua Barney." Like most Naval muster and payrolls of this era, there is no mention of race or ethnicity.47

47. Pay Rolls, 1813-1814, Chesapeake, Miscellaneous Records of the Navy Department, Miscellaneous Records of the Office of Naval Records and Library, 1803 -1859, Roll 0203, p. 6, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC.

Only rarely on the "Register of Patients at Naval Hospital Washington, DC" are men identified as Black. For example patient #35 Harry Jones, a young African American, is identified as "Black, Boy wound, Bladensburg" 1814.48

48. Sharp, John G.M., Register of Patients at Naval Hospital Washington, DC, with the names of the American Wounded from the Battle of Bladensburg, 2018, Naval History and Heritage Command, Washington, D.C. https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/r/register-patients-naval-hospital-washington-dc-1814.html

Cesar Wentworth, Muster Gunboat 138, #36 Cesar Wentworth O.S., Wentworth a Black man fought with the Flotilla from Cedar Point to Bladensburg and the Battle of Baltimore, see Shomette, p. 429 n29.

David Bell, Chesapeake Flotilla, #959 Negro David Bell O.S. paid through April 1815.

William Johnson, note attached to the muster, regarding "William Johnson my Boy left on the 15 of Nov 1813 and Frank came the same day. The ration continued to be stopped as before, both joined the Flotilla the same day. [Signed] Jos Tarbell."49 John was enrolled as a Ordinary Seaman and his pay and rations went to the slaveholder.

49. Muster Rolls 1809-1814 Chesapeake, Miscellaneous Records of the Navy Department, Miscellaneous Records of the Office of Naval Records and Library, 1803-1859, Roll 0030, p. 3, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC.

* * * * * *

Documents

Captain Joshua Barney, Flotilla Service, to Secretary of the Navy, William Jones, gives an account of Bladensburg

Farm at Elkridge, Augt 29th 1814

Sir,

This is the first moment I have had it in my power to make a report of the proceedings of the forces under my command since I had the honor of seeing you on Tuesday the 23d instant. at the Camp at the "Old fields," on the afternoon of that day we were informed that the Enemy was advancing upon us, The Army was put into order of battle and our positions taken, my forces were on the right, flanked by the two Battalions of the 36 & 38th Regiments where we remained some hours, the enemy did not however make his appearance. A little before sun set, General Winder came to me and recommended that the heavy Artillery should be withdrawn with the exception of one 12 lb. to cover the retreat; We took up our line of march and in the night entered Washington by the Eastern Branch Bridge, I marched my Men &c to the Marine Barracks and took up Quarters for the night, myself sleeping at Comr. Tingeys at the Navy yard, About 2 o’clock. Genrl. Winder came to my Quarters and we made some arrangements.

In the morning I received a note from Genrl. Winder and waited upon him, he requested me to take command, and place my Artillery to defend the passage of the Bridge on the Eastern Branch as the enemy was approaching the City in that direction, I immediately put my guns in Position, leaving the Marines & the rest of my men at the Barracks to wait further orders. I was in this situation when I had the honor to meet you, with the President, & heads of Departments, when it was determined I should draw off my Guns & men and proceed towards Bladensburgh, which was immediately put into execution; on our way I was informed the enemy was within a mile of Bladensburgh we hurried on.

The day was hot, and my men very much crippled from the severe marches we had experienced the preceding days before many of them being without shoes which I had replaced that morning I preceded the men and when I arrived at the line which separates the District from Maryland the Battle began, I sent an officer back to hurry on my men, they came up in trot, we took our position on the rising ground, put the pieces in Battery, posted the Marines under Capt. Miller and the flotilla men who were to act as Infantry under their own officers, on my right to support the pieces, and waited the approach of the Enemy, during this period the engagement continued the enemy advancing,- our own Army retreating before them apparently in much disorder, at length the enemy made his appearance on the main road, in force, and in front of my Battery, and on seeing us made a halt, I reserved our fire, in a few minutes the enemy again advanced, when I ordered an 18 lb. to be fired, which completely cleared the road, shortly after a second and a third attempt was made by the enemy to come forward but all were destroyed, The enemy then crossed over into an Open field and attempted to flank our right, he was there met by three twelve pounders, the Marines under Capt. Miller and my men acting as Infantry, and again was totally cut up, by this time not a Vestige of the American Army remained except a body of 5 or 600 posted on a height on my right from whom I expected much support, from their fine situation, The Enemy from this period never appeared in force in front of us, they pushed forward their sharp shooters, one of which shot my horse under me, who fell dead between two of my Guns; The enemy who had been kept in check by our fire for nearly half an hour now began to out flank us.

About 2 or 300 towards the Corps of Americans stationed as above described, who, to my mortification made no, resistance, giving a fire or two and retired, in this situation we had the whole army of the Enemy to contend with. Our Ammunition was expended, and unfortunately the driver of my Ammunition Wagon had gone off in the General Panic, at this time I received a severe wound in my thigh. Capt. Miller, was Wounded, Sailing Master Warner, Killed, actg, sailing Master Martin Killed, & sailing Master Martin wounded, but to the honor of my officers & men, as fast as their Companions & mess mates fell at the guns they were instantly replaced from the Infantry. Finding the enemy now completely in our rear, and no means of defense, I gave orders to my officers and men to retire - Three of my officers assisted me to get off a Short distance- but the great loss of blood occasioned such a weakness that I was compelled to lie down, I requested my officers to leave me, which they obstinately refused, but upon being Ordered they obeyed, one only remained.

In a short time I observed a British soldier and had him called, and directed him to seek an officer. In a few minutes an officer came, on learning who I was, brought General Ross & Admiral Cockburn to me, Those officers behaved to me with the most marked Attention, respect, and politeness, had a Surgeon brought and my wound immediately dressed. After a few minutes conversation, the General. Informed me, (after paying me a handsome compliment) that I was paroled and at liberty to proceed to Washington or' Bladensburgh, as also Mr. Huffington who had remained with me, offering me every assistance in his power, giving orders for a litter to be brought on which I was carried to Bladensburgh . Capt. Wainwright, first Capt. to Admiral Cochrane, remained with me and behaved to me as if I was a brother – During the stay of the enemy at Bladensburgh I received the most polite attention from the officers of the Navy & Army. My wound is deep, but I flatter myself not dangerous, the Ball is not yet extracted, I fondly hope a few weeks will restore my health, and that an exchange will take place, that I may resume my Command or any other that you and the President may think proper to honour me with, yours respectfully .[Signed] Joshua Barney

On the side of the Americans the slaughter was not so great. Being in possession of a strong position, they were of course less exposed in defending, than the others in storming it; and had they conducted themselves with coolness and resolution, it is not conceivable how the battle could have been won. But the fact is, that, with the exception of a party of sailors from the gun-boats, under the command of Commodore Barney, no troops could behave worse than they did. The skirmishers were driven in as soon as attacked, the first line gave way without offering the slightest resistance, and the left of the main body was broken within half an hour after it was seriously engaged. Of the sailors, however, it would be injustice not to speak in the terms which their conduct merits. They were employed as gunners, and not only did they serve their guns with a quickness and precision which astonished their assailants, but they stood till some of them were actually bayoneted, with fuses in their hands; nor was it till their leader was wounded and taken, and they saw themselves deserted on all sides by the soldiers, that they quitted the field.50

50. Gleig, p. 89.

* * * * * *

The 1814 Register of Patients at the Naval Hospital Washington provides a unique glimpse of the aftermath of battle and a record of the lives of individual sailors, marines, soldiers, and civilians, many who were part of the Chesapeake Bay Flotilla from their admission to discharge. The Register, covers the period 2 June to 30 December 1814, is one of our most important primary sources for the names and units of American casualties at Bladensburg, see thumbnail https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/r/register-patients-naval-hospital-washington-dc-1814.html

Commodore Joshua Barney writing to Secretary of the Navy, William Jones, 29 October 1814, re the treatment of his men and his Purser John S. Skinner, USN.51

51. John S. Skinner, appointed Purser USN, 26 March, 1814, last appearance on Records of Navy Department, 1815, resigned. Officers - Continental & US Navy/Marine Corps 1775-1900. Naval History and Heritage Command, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/o/officers-continental-usnavy-mc-1775-1900/navy-officers-1798-1900-s.htm

Baltimore Oct. 29th 1814

Sir,

The continual losing of my men distresses me beyond measure. I have turned my views to remedy the misfortune and on consulting with Mr. Beatty, to think the money may be raised here if you will authorize it, if only for the amount advance as to engage the men for another year; leaving the balance due them out of the question until Mr. Skinner can or will make out the accounts, (if this had been done according to my orders the whole amount we wanted could have been raised) In plain terms he is not fit to be a purser, I have never been able to obtain from him a simple muster book, and altho continually demanding one from him; I know how many men I have, yet I do not know when the men entered, when dead, when discharged, when run, or in fact a single circumstances which his duty directs him to do – he is never present, his farm in Calvert County, his flag of truce business etc, with great desire to be out of danger all summer when we were in Patuxent has deprived me of any assistance whatever from him. Mr. Skinner, Sir, is a worthy Citizen, and I esteem as friendly man, but that will not do, his Duty has been grossly neglected as much from ignorance of the officer as anything else. My reputation among my men and the Citizens has been injured, as well as the public service and I hope an end will be put to it, by his immediate, and final settlement of his accounts, for the men are clamorous indeed.52

I am very respectfully your obedient servant

[Signed] Joshua BarneyTo: Honorable William Jones

52. Joshua Barney to William Jones, 29 Oct 1814, Letters Received by the Secretary of the Navy from Captains, (“Captains Letters””), 1805-61; 1866 -85, volume 40, letter 76, Roll, 0040, pp. 1-3, Natonal Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC.

Martin, William.

Sailing Master, 12 January, 1814. Discharged 15 April, 1815.Martin, James.

Sailing Master, date not known. Discharged 15 April, 1815.