BROOKLYN NAVY YARD 1841 NAVAL COURT OF INQUIRY re COMMODORE JAMES RENSHAW

AND CHARGES OF JOB PATRONAGE AND FAVORITISM

By John G M Sharp

Introduction

In February 1841 the new Secretary of the Navy George E. Badger ordered a court of inquiry to investigate and examine the official conduct of Commodore James Renshaw (1784-1846) while Commandant of the Naval Station New York (Brooklyn) in the years 1839, 1840 and 1841. The court headed by Captain James Biddle was directed to investigate complaints preferred by Navy Yard department heads and employees. The complainants claimed Renshaw had engaged in political patronage and had attempted to remove long service employees for purely political reasons.1

1. Navy Court Martial Records and Court of Inquiry, 1799-1867, re Captain James Renshaw, Volume 36, Case 738, Page pp. 32-33, Roll 0038, Case Range 729-747, Year Range 14 October 1840 – 23 October 1841, National Archives and Records Administration. Hereafter Renshaw Inquiry.

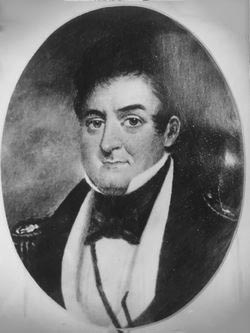

Commodore James Renshaw

Commodore Renshaw had in fact requested this inquiry. A Naval Court of Inquiry, unlike a Court Martial, is an investigative body that lacks the power to impose punishments, yet a negative outcome could dismantle a career.2

2. Plante, Trevor K. “Civil War Union Court-Martial Case Files” Prologue Winter 1998, Vol. 30, No. 4 Genealogy Notes, National Archives and Records Administration.

This record of the 1841 Court of Inquiry is valuable both as legal record and for the extensive testimony of officers and civilians. The minutes of the inquiry stand as a reflection of turbulent era and its 296-page record allows modern historians opportunity to glimpse the day-to-day work and concerns of the Brooklyn Navy Yard employees. By 1841 such inquiries were not new: from the Brooklyn shipyard’s beginning, scandals and fractious political fights were a feature of life. In response, employees became increasingly watchful and restive to proposed changes in their workplace. As early as 1808, Commodore Isaac Chauncey found himself forced to explain to the Secretary of the Navy his decision (in response to a petition of shipyard workers) to retain the unpopular Christian Burgh, master shipwright and entrepreneur.3 Similarly, in 1823 a Court of Naval Inquiry officially reprimanded Captain Samuel Evans USN, commandant from 1813-1823, for misconduct in mixing his public and private business.4

3. Sharp John G., Brooklyn Navy Yard. https://genealogytrails.com/ny/kings/navyyard.html

4. Court Martial of Samuel Evans, National Archives and Records Administration Record Group 125, Records of the Navy Judge Advocate, number 403, Entry 26B.

Allegations that political parties held sway over shipyard job placement by 1841 had become widespread. In addition, such claims of favoritism, nepotism and misuse of government funds became more frequent. This situation would remain largely unchanged until 1883 with the passage of the Pendleton Act and the creation of the modern Merit System.5

5. Sharp, John G., History of the Washington Navy Yard Civilian Employees 1799-1962 Naval History and Heritage Command, p.57, http://www.history.navy.mil/books/sharp/WNY_History.pdf

Transcription: This transcription was made from digital images of letters to the Secretary of the Navy and documents, such as the proceeding of the 1841 Naval Court of Inquiry, preserved in the records of the Navy Department, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC. In transcribing all passages from the letters and memorandum, I have striven to adhere as closely as possible to the original.

John G. M. Sharp 21 June 2023

Naval Career of Commodore James Renshaw

James Renshaw was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1784 and appointed Midshipman, 7 July, 1800; he was promoted Lieutenant 25 February, 1807, Master Commandant 10 December 1814 and Captain 3 March, 1825. The young Renshaw had served in the Barbary Wars and as a Midshipman was in the ill-fated crew of the frigate USS Philadelphia. When she ran aground on October 31, 1803, the Philadelphia was captured by the Barbary Pirates. The frigate's commanding officer Commodore William Bainbridge, along with his officers and crew remained imprisoned until the Treaty of Tripoli was signed on June 4, 1805. On 6 November 1804 writing to Captain John Rodgers, Midshipman Renshaw described conditions within Tripoli Prison for officers.

Our situation at present, my dear Sir, is beyond conception. Nearly Six months of Solitary imprisonment have elapsed since the doors of our prison opened for any purpose other than supplying us with substance, its true [we] have been treated with more leniency than we had reason to expect of a Barbary Prince, but how much better put to hard labor as our crew then we could feel the fresh air, which is so essential to human nature. … My Anxiety to hear from friends in the U.S. is very great as I have never received a line from them since my captivity …6

6. Naval Documents Related to the United States Navy Wars with the Barbary Powers, Volume V, Editor Dudley Knox, (United States Government Printing Office, Washington D.C., 1944), pp 87, 124 -125.

Probably unknown to Renshaw, the Philadelphia officers had an entirely different captivity experience from the ordinary seamen as the Pasha, Yusuf Karamanli, apparently honored European standards for the treatment of American officers but only had loathing for common sailors.7

After a long ordeal in captivity, on 31 October 1805, the frigate USS President arrived in Norfolk,Virginia, with Captain James Bainbridge and his officers. Midshipman James Renshaw was finally home.8

7. Zeledon, Jason Raphael, The United States and the Barbary Pirates: Adventures in Sexuality, State-Building and Nationalism, 1784-1815, pp. 162-163 PHD thesis ,UC Santa Barbara, 2016. https://escholarship.org/content/qt9pf6v1wt/qt9pf6v1wt.pdf?t=prk17r

8. 31 October 1805, The Bee, (Hudson, New York) , quoting the Norfolk Ledger.

On 5 September 1808 James Renfrew’s name appeared in The New York Evening Post and informed the public that Lt. Renfrew, as commander of Gun-Boat No. 40, had detained the schooner Speedy on 19 August 1808 near the Southside of Long Island. The article noted that Captain of the Speedy [David Petty] alleged his vessel was boarded and searched and that after that he was allowed to proceed about one mile to the windward, when he was fired at, compelled to bear away and came under the lee of the gun-boat, when the commander [Renshaw] demanded he come aboard and pilot him into fire-Island inlet. At which time Captain Petty stated he would consent to do so for ten dollars. Renfrew then replied, “he would be damned if he would give ten cents.” Captain Petty accused Renshaw of holding him for three days on the gunboat and that he was placed in irons with handcuffs on his wrists and shackles on his legs for one whole day and night.9

9. 5 September 1808 Evening Post (New York, New York), p. 2.

“No one suffered more than Sailors.”

The Embargo Act of 1807, passed at the request of President Thomas Jefferson, was a general trade embargo on all foreign nations enacted by the United States Congress. This embargo represented an attempt to persuade Britain to stop impressment of American sailors and to respect American sovereignty. In New York City the act quickly became unpopular with the business and maritime leaders. Most historians now consider this a colossal blunder as it caused no appreciable harm to the British economy but shattered the American. United States exports tumbled 80% while imports fell 60%. Part of the Embargo Act bared U. S. merchant vessels from leaving port.

In 1808 New York City saw 120 firms go out of business and twelve hundred new debtors were added to the insolvency rolls. As a result of the Act, thousands of American sailors became unemployed. As historians Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace remind us, the Embargo Act devastated the maritime trade and “no one suffered more than sailors”10 As a result of the embargo, about 500 merchant vessels in the harbor were lying useless and rotting for want of employment, while thousands of seamen were destitute of bread.11 The passage of the Embargo Act led New York City to widespread disdain for the Jefferson Administration and for merchants and shippers to resort to smuggling goods in and out of the harbor. This may have been in Renshaw’s mind as his crew boarded the Speedy.

10. Burrows, Edwin G. and Wallace, Mike, Gotham, A History of New York City to 1898 (Oxford University Press, New York, 1999), pp. 410-412.

11. Burrows, Edwin G. and Wallace, Mike, pp. 412-413.

A Court of Naval inquiry on 26 September 1808 convened in New York harbor on the Bomb ketch Aetna to investigate the conduct of Lt. James Renshaw on charges alleged by David Petty master of the schooner Speedy of Brookhaven and published in a newspaper entitled the New York Commercial Advocate.12 The Court of Inquiry heard evidence was from Captain Petty and the crew of the Speedy and likewise from James Renshaw and the crew of the Aetna. They also examined documentary evidence supplied by Renshaw from accounts written in various New York City newspapers.13

Similarly, in November 1808, Lt. James Renshaw was indicted in the state of New York for the offense of dueling Trial of People v. Lieutenant Renshaw.14 The indictment stated,

[James Renshaw] “did, by a certain writing, request and invite one Joseph Strong of the ward, city and county aforesaid, to meet him the aforesaid James Renshaw, with intent to fight a duel against the form of the statute in such case made and provided, and against the peace of the people of the state of New York and their dignity.

12. Navy Court Martial Records and Court of Inquiry: 1799 -1867 re Lieutenant James Renshaw, Volume 2,, Case 52, Page 1, Roll 0004, Case Range 30-74, Year Range 16 August 1805 to 16 January 1808, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington D.C. Hereafter Renshaw Inquiry 1808.

13. Renshaw Inquiry, 1808, pp. 4, 5, 6, 8.

14. Renshaw, James, The Trial of Lieutenant Renshaw of the U.S. Navy, Indicted for Challenging Joseph Strong, Esq., Attorney at Law, to fight a Duel (Frank, White, and Company, New York 1809), pp. 1-10. https://books.google.com/books?id=jloPAAAAIAAJ&q=new+york#v=onepage&q=new%20york&f=false

Lt. Renshaw was again in the news when the Public Advertiser, on 14 November 1808, reported he was acquitted of all charges related to dueling. That paper then charactered him as” a worthy and young meritorious officer …singled out as a mark of party hatred”. They also noted the charges had "endeavored to destroy the reputation” of Lieutenant Renshaw.15

However, prominent New York attorney Joseph Strong would for the next thirty years represent Renshaw’s creditors represent Renshaw’s creditors and relentlessly pursue him for debt. While dueling caught the public eye, as naval historian Christopher McKee has noted, duelists in the United States Navy were often young impetuous officers like Renshaw. During the period before 14 February 1815, dueling pistols claimed the lives exactly eighteen naval officers.16 While dueling was not illegal, it was definitely frowned upon. Among the eighteen naval officers killed in duels prior to 1815, twelve were midshipmen. Though this dreadful “custom lingered on after the end of the War of 1812 to claim its occasional victim, men famous and men obscure,” fortunately Lt. Renshaw was not among them.”17

15. 14 November 1808, Public Advertiser, (New York, New York), p. 2.

16. Christopher McKee's A Gentlemanly and Honorable Profession: the Creation of the U.S. Naval Officer Corps, 1794-1815 ( Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 1991), p. 403.

17. McKee, p. 406

On 8 April 1809 James Renshaw married Mary Schenk.18

18. 8 April 1809 Weekly Museum, (New York, New York), p. 2.

In 1812 Renshaw’s problems with debt and his creditors reappeared to again plague the young officer so much so that he notified the Secretary of the Navy Paul Hamilton. He complained that,

I have the honor of addressing you on a subject that I was much in hopes I should not be obliged to call your attention to again, but the fiend disposition of the man [Joseph Strong] I have so long to contend with, has rendered his persecution against me with ten-fold with tenfold violence …

His unjust claims against me, all from our partial settlement, the notes I gave him were payable yearly, you undoubtedly recollect that I received in Washington but two hundred dollars, a half-pay due that I was necessarily obliged to apply to the purposes that require no explanation (my little family) from his getting the greater part of it has been an excuse for his infamous proceeding, in fact, I have been reduced in a pecuniary way, as low as possible, by this man and have a few days past given up my little property I held from my Father‘s estate and applied for the benefit of the state [New York] as you will observe from the enclosed, it was a measure of extreme & repugnant to my feeling, but the only way I could pursue to extricate myself forever from the fangs of Mr. Strong. …Sir let me solicit the favor of you putting me on full pay for three ensuing months, as it will enable me to meet the call of my attorney counsel, expenses of the insolvent court and insure a subsistence without my misfortunes becoming dependent on another that I have the honor to serve upwards of twelve years…”19

19. James Renshaw to William Jones, 24 February 1812, p.1, Officers' Letters to the Secretary of the Navy by officers assigned to ships, stations, and Navy bureaus (“Navy Officers Letters”), Volume 17 & 18, Roll 0009, RG 45, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington DC.

The question arises as to why James Renshaw did not file for bankruptcy? First, the national bankruptcy law was enacted in 1800. This law, however, was of little help to most debtors as it was very pro-creditor oriented. Only involuntary bankruptcy cases were allowed and only merchants could be debtors. To obtain a discharge from debts, two thirds of creditors by number and value of claims had to consent to the discharge. Secondly, and most importantly, the social stigma Commodore James Renshaw attached to his financial problems can be seen in both his letters and the Court of Inquiry transcript.

Lt. Renshaw also served during the War of 1812.20 His rise through the ranks as a young officer, while not spectacular, was steady. An ardent desire for promotion is reflected in his letters to Secretary of the Navy William Jones.21, 22 In response to Renshaw’s letter of 9 September 1813, a clearly irritated Jones wrote,

I have also received several letters from yourself and Brother, [Richard Renshaw] complaining of the injustice done to you in the later promotions and urging your claims with much zeal and perseverance, with the avowed object of exhorting from the Department a pledge of promotion, either immediate, or at the next session. Both the manner and the purpose are too exceptional to command acquiescence, or pass without notice.23

20. Naval Documents Related to the United States Navy wars with the Barbary Powers, Volume V, Editor Dudley Knox, (United States Government Printing Office, Washington DC, 1944), pp. 87, 124.

21. James Renshaw to William Jones, 12 December 1813, Officers' Letters to the Secretary of the Navy by officers assigned to ships, stations, and Navy bureaus (“Navy Officers Letters”), Volume 23-24, Roll 0012, RG 45, National Archives and Records Administration , Washington DC.

22. Richard Renshaw to William Jones 9 August 1813, DNA, RG 45, MLR, 1813, Volume 5, No 89 (M124,Roll No. 57.)

23. The Naval War of 1812: A Documentary History, Volume II, 1813 editor William S. Dudley (Naval Historical Center, Department of the Navy, Washington DC,1992), pp. 209-210.

The war brought opportunity for ambitious officers lie Renshaw to rise in the ranks and make a name. In April 1814 he was given command of the 14 gun brig USS Rattlesnake, formerly the brig Rambler. Under Renshaw the Rattlesnake is said to have captured eight merchant vessels in the eastern Atlantic, north of the equator. However, on 22 June 1814 her luck ran out when she was overtaken by the 50 gun British frigate Leander. The Rattlesnake and crew were taken to Halifax, Nova Scotia, where Renshaw and his officers were placed on parole. Returning to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Renshaw requested from the Secretary of the Navy, a Court of Inquiry regarding the loss of the Rattlesnake.24 Such a Court of Inquiry was standard practice following the loss of a ship, and no blame was affixed to Renshaw or his officers since their brig was heavily outgunned.24a

24. Renshaw, James, 21 November 1814, Officers' Letters to the Secretary of the Navy by officers assigned to ships, stations, and Navy bureaus (“Navy Officers Letters”), Volume 25-28, Roll 0013, RG 45, National Archives and Records Administration , Washington DC.

24a. Cooper James Fenimore, The History of the Navy of the United States, Volume 2, (A & W., Galignani, Paris, 1839), p. 188. https://books.google.com/books?id=nJ06AAAAcAAJ&pg=PA188&dq=James+Renshaw,+James+Fenimore+Cooper, +rattlesnake&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi84byh5tT_AhUkq4QIHXvoC8IQ6AF6BAgBEAI#v= onepage&q=James%20Renshaw%2C%20James%20Fenimore%20Cooper%2C%20rattlesnake&f=false

A subject that would long trouble Renshaw was the distribution of the prize money for the enemy vessels taken while he was commanding officer of the brig Rattlesnake. Writing to the Secretary of the Navy on 8 March 1814, he complained that Commodore James Murray had received his share of the money realized from the vessels in question but he was still waiting.25

25. James Renshaw to William Jones, 8 March 1814, p.1, Officers' Letters to the Secretary of the Navy by officers assigned to ships, stations, and Navy bureaus (“Navy Officers Letters”), Volume 25 to 28, Roll 0013, RG 45, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington DC.

Commodore Isaac Hull, a hero of the War of 1812, had known Lt. Renshaw as a subordinate and did not hold him in high opinion. Writing in 1814 to the Secretary of the Navy on hearing of Renshaw’s appointment to command the USS Enterprise, he remarked dryly, “The Enterprise, I presume, will not be very enterprising”26 To William Jones, Hull noted, “the conduct of Captain Renshaw is not at all times as correct as it ought to be as commander in the Navy, but perhaps a cruise or two will give a more correct idea of service that he now possesses.”27 Hull’s principal biographer Linda Maloney, comments, “Apparently Renshaw was a martinet and was incapable of getting along with his superiors or inferiors.”28

26. Maloney, Linda M. The Captain from Connecticut: The Life and Times of Isaac Hull, (Northeastern University Press, Boston, 1986), pp. 234-235.

27. Isaac Hull to William Jones, 13 January 1814, Letter Received by the Secretary of the Navy from Captains, 1805 to 1861, 1 January 1814 to 28 February 1814, Volume 34, Letter 29, p.1, Roll 0034, RG 260, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington DC.

28. Maloney, Linda M., p. 234.

Renshaw problems with his superiors are evident again when on December 7, 1831, the Secretary of the Navy Levi Woodbury informed Commodore James Renshaw that he would be passed over for command of the Brazilian squadron because of “representations unfavorable” to his character on file with the Board of Navy Commissioners. Protesting that he had been told nothing of such charges, Renshaw asked for the name of his accuser. On December 12, Woodbury referred him to Board president Captain John Rodgers (1773-1838).

Capt. Rodgers described the allegations to Renshaw and named his former shipmate, Master Commandant Benjamin Cooper (1793-1850), as their source. On December 15 and 22, Renshaw wrote Rodgers asking him to state Cooper’s charges in writing. Rodgers made no reply. Renshaw then solicited testimonials from officers who had sailed with him and Cooper and forwarded them on to Woodbury. On January 25, 1832, Woodbury wrote Renshaw that henceforth his requests for command would “be entitled to full and favorable consideration, in connection with the requests of others of the same rank.” Again, on January 30, 1832, Renshaw protested his treatment to the Navy Board, declaring that “malicious and insidious representations secretly made, affecting his reputation, cannot be forgiven.”

On February 1, he went further and published a pamphlet addressed to his fellow Navy officers. Here he included his exchanges with Woodbury, Rodgers, and the Navy and branded Cooper’s charges as “vile” and “too gross in their nature” to be put into print. The two closing paragraphs of Renshaw’s pamphlet praised Woodbury’s “candor and frankness,” pointedly exonerated the other two Board members, captains Charles Stewart and Daniel Todd Patterson, of complicity in “the machinations of invidious and malicious slanderers,” and observed that Rodgers had still yet “to say why he has countenanced the dark and unseen attacks upon my character,” in defiance of “common justice” (DNA-RG 45, M125-167).

Rodgers wrote Woodbury on or near February 9, complaining that Renshaw’s pamphlet “manifested a degree of insubordination which, if passed over, may produce serious injury to the service” (DNA-RG 45, M125-167). On February 24, four days after this note from Andrew Jackson, Woodbury replied to Rodgers that by Jackson’s direction, “no further step is deemed necessary to be taken by the Department, in relation to the subject” (DNA-RG 45, M149-21).

The delicacy arose because the junior captain given command of the Brazilian squadron, in preference to Renshaw, was George Washington Rodgers (1787-1832), John Rodgers’s younger brother.29

29. The Papers of Andrew Jackson, Volume X, 1832, editor Daniel Feller, (The University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville, 2016), pp. 100-101.

Complaints and Rumors

In 1840 Commodore Renfrew’s new assignment to the Brooklyn Navy Yard, where many civilian employees had supported the Whig candidate, and feared Renshaw might use his position for both personal and political ends. For over a year, rumor and speculation were widespread regarding possible political machinations at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. In July 1840, the New York American highlighted “strange and discreditable rumors about the tampering with workmen and others at this Yard on the score of their politics and of urgent, systematic, and pertinacious efforts by partisans of the Administration”.30

30. Long Island Star (Brooklyn, New York) 6 July 1840, p. 2, here quoting the New York American.

The beginning of Commodore Renshaw tenure in office unfortunately coincided with the 1840 presidential election which was bitterly contested, but in the final count New York voters favored the Whig candidate, William Henry Harrison, over Democratic candidate Martin Van Buren. Harrison had won New York by a narrow margin, votes with the Whig Party numbering 226,001, the Democrat Party 212,733 and the Liberty Party 2,809. The national voting patterns were similar, and Whig candidate William Henry Harrison was elected president. In the Brooklyn Navy Yard anxious employees increasingly feared their new commandant might replace them as he was perceived to be Democrat.

Complaint of creditor James Patterson

Complaints against Renshaw also came from outside the shipyard. For example, letters from Princeton, New Jersey, business man James Patterson, a creditor to Commodore Renshaw for a substantial sum. The debt apparently was incurred by the Commodore in 1829. Patterson letters requesting Renshaw to make prompt payment of the debt were followed by others of William S. Sears, James Patterson’s loan agent, as late as 1 April 1841.

As a whole the letters reflect how hard Commodore Renshaw was pressed to make timely payments.31 The rather loose rules of evidence governing a Naval Court of Inquiry put the Commodore’s financial plight on full public display. In his rebuttal Renshaw acknowledge the debt and proclaimed his humiliation with the crushing burden of now being a public debtor.32

31. Exhibit M, pp. 223-248.

32. Adding to his misery Commodore Renshaw’s, spouse Maria, was ailing during much of the Inquiry and died on 7 January 1842. 14 January 1842, (Alexandria Gazette, Alexandria Virginia, 1842), p. 3.

To the court Renshaw stated,

"Let no man presume to judge the feelings of my heart during this dark period of my life. What I suffered will perhaps be never known save to my maker. Not even to her who of all others has the best right to my confidence. Let no man say it was right, let no man judge me, let no man who has not felt it presume to speak of the agony which the proud man endures from Debt, Debt, Debt."33

33. Renshaw Inquiry, p. 289.

Yet another complaint came from the editor of the Long Island Star who alleged the July 1840 removal of Navy Yard master painter John Dean was political “is to be found in the fact that he is Whig.” The article took care not to blame Commodore Renshaw for Dean’s removal but instead “by direct application at Washington by a Brooklyn political committee!!”34 The removal of John Dean was later offered as Exhibit H during the 1841 Commodore Renshaw’s Court of Inquiry.35 Also offered was Exhibit I, the discharge and removal of twenty one laborers, by order of Commodore Renshaw dated 28 August 1840.36

34. Long Island Star (Brooklyn, New York ) 6 July 1840, p. 2.

35. Renshaw Inquiry, p. 214, Exhibit H.

36. Renshaw Inquiry, p. 215, Exhibit I.

Newspapers like the National Intelligencer had somewhat misleadingly reported that “Commodore Renshaw has been removed from the station at the Brooklyn Navy Yard and Commodore Nicholson appointed in his stead. Another charge preferred against Commodore Renshaw, it is said, was that he allowed the workmen in the Navy Yard only a half day to attend the polls.”37

37. National Intelligencer, New York, February 25, 1841.

Complaints of Political Favoritism and Patronage

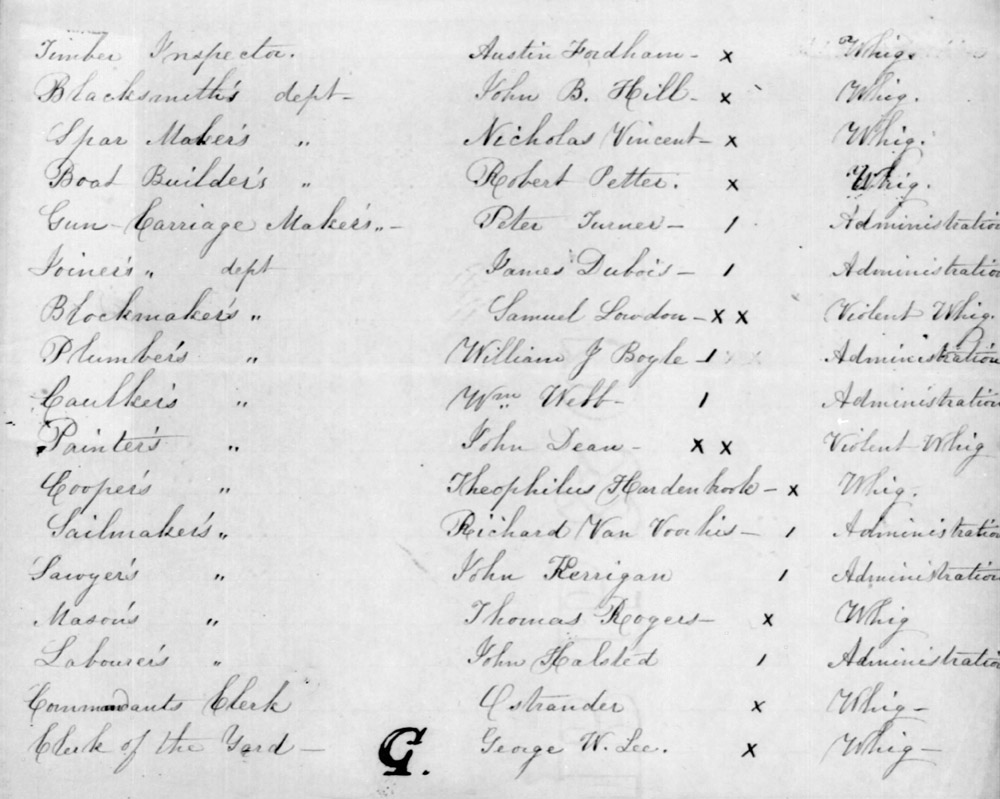

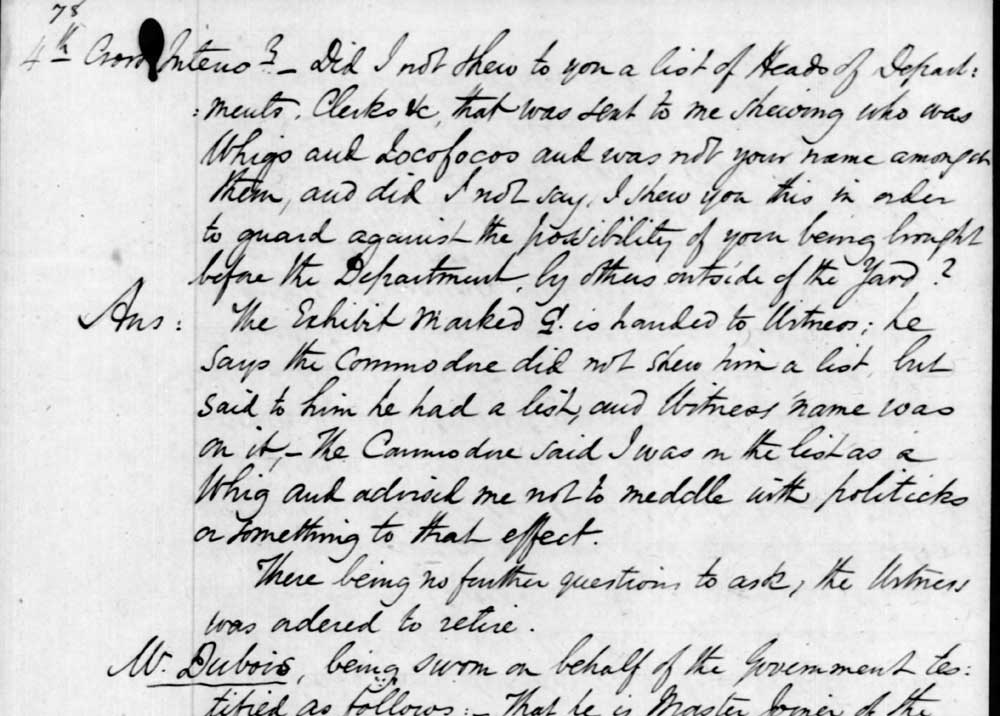

“The Commodore said I was on the list as a Whig and advised me not to meddle with politics or something to the effect.” Testimony of George W. Lee

The List

The Naval Court of Inquiry heard evidence for two weeks. One piece of evidence offered against the Commodore was a handwritten document, labeled “Exhibit G”. This was a list of important civilian positions in Brooklyn Navy Yard. Department heads and other significant jobs were listed by name, job and political affiliation. The list by either Commodore Renshaw, or someone acting on his behest, was offered as evidence of alleged favoritism toward Democrats. Rumors abounded its mere existence frightened Whig employees rightly feared this list would govern all appointments and dismissals.

Exhibit G., Renshaw Inquiry p. 213.Exhibit G is transcribed below into table format with department heads, alleged political affiliation followed by designation X, XX, or 1.

Department Heads Employee Name Party Timber Inspector Austin Fordham Whig Blacksmiths dept. John Hill Whig Spar Makers Nicholas Vincent Whig Boat Builders Richard Peter Whig Gun Carriage Makers Peter Turner Administration Joiners dept. James Dubois Administration Block makers dept. Samuel Lowden Violent Whig Plumbers dept. William J. Boyle Administration Caulkers dept. Wm Hall Administration Painters dept. John Dean Violent Whig Coopers dept. Theophilius Hardenbrook Whig Sail makers dept. Richard Van Voorhis Administration Sawyers dept. John Kerrigan Administration Masons dept. Thomas Rodgers Whig Laborers dept. John Halsted Administration Commanders Clerk D. Stander Whig Clerk of the Yard George W. Lee Whig On the list, the author of Exhibit G recorded his perception of each of the Navy Yard’s seventeen department heads, and by each employee, their supposed political affiliation. These were: Whig, Violent Whig, and Administration. Although nowhere stated the designation 1 and “Administration”, is a perceived adherent of the Democratic Party. Those Whig employees with a double XX by their name were thought in eminent peril of removal. The Whig Party was a political party which existed in the United States during the mid-19th century. The Whig base of support was centered among entrepreneurs, professionals, planters, social reformers, devout Protestants, particularly evangelicals, and the emerging urban middle class. It had much less backing from poor farmers and unskilled workers. At the Brooklyn Navy Yard, Whig supporters favored improvements in port infrastructure as federal largesse underwrote lighthouses and provided half a million dollars for work on the harbor forts and Navy Yard.38

38. Burrows, Edwin G. and Wallace, Mike, Gotham, A History of New York City to 1898 (Oxford University Press, New York, 1999), p. 822.

Testimony of Clerk of the Yard, George W. Lee

George W. Lee, silhouette, 1833During the inquiry, Exhibit G, the list was mentioned by Commodore Renshaw, while questioning his former clerk George Washington Lee. George W. Lee (1792-1878) was Clerk of the Yard for nearly fifty years, as such he worked closely both with the Commodore and the various department heads.39

39. George Washington Lee was born in Baltimore, Maryland, on October 24, 1792. He was of English descent and attended the Episcopalian church in Brooklyn, New York. He died on February 2, 1878, in Brooklyn and is buried in Greenwood Cemetery there. He was married to Arab Ella McClure on May 21, 1833, at St. Ann’s Episcopal Church in Brooklyn; she was the sister of Commodore William J. McCluney.

My thanks to Ms. Susan Clark Levine for the helpful Lee family genealogical information and the wonderful 1833, silhouette of George W Lee. A separate article regarding George W. Lee and his wife Arabella McCluney will be posted shortly.

Testimony of George W. Lee

George W. Lee began his testimony on behalf of the government by stating, “I am employed as Clerk of the Yard and have been employed since 16th March 1833; as Clerk it’s my duty to muster the Mechanics and laborers at work in the Yard.” George W. Lee was first employed at the Brooklyn Navy Yard as Captain’s Clerk in August 1819.40 Lee’s position made him responsible for the records maintained in the commandant’s office and in this capacity he worked closely with Commodore Renshaw. His testimony was both vital to the prosecution and the defense.

40. Records of General Court Martials and Courts of Inquiry of the Navy Department, 1799-1867, Court of Inquiry of Samuel Evans, Volume 14, Case Range 403.5-413, p. 400, 10 June 1823 to 23 January 1824, Case 403½, p. 400, Roll 0016,RG 125, National Archives and Record Service, Washington DC.

Like Lee all civilian employees in 1841 served at the pleasure of the commanding officer; there was no civil service or any regulations to afford them protection from arbitrary dismissal. For employees testifying at any official proceeding was always fraught with peril, less they incur their superior’s or the department’s displeasure. Lee, though, was a man of considerable courage. He had worked at the Brooklyn Navy Yard since 1819. In 1823 he had declined to fight an angry midshipman, Henry B. Potter, who had challenged him to a duel, which Lee properly declined. That very same evening the midshipman enraged at what he thought was a further slight to his honor, with a friend, attacked George Lee at his residence with a clear intent to maim or murder. Lee later wrote,

Mr. Potter there with a drawn dirk in one hand and a club in the other – After some impertinent language, he made a furious attack upon me but I succeeded in taking it from him & handed it to a person who was at hand to receive it, without any other injury than a slight wound in the hand - The dirk is now in my possession –41

41. Letters Received by the Secretary of the Navy from Captains ("Captains' Letters") 1805-61; 1866-85, George W. Lee to Samuel Evans 23 Dec 1823, Volume 85, 8 Nov 1823 to 31 Dec 1823, Letter Number 113, Roll 0085, M125, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington DC.

In 1841 New York City had no municipal police department.42 Faced with a determined assailant, the quick-thinking Lee had to rely on his own strength and courage. Although Lee was slightly wounded, he was able to disarm his attacker. Midshipman Potter months later subsequently resigned from the Navy.43

42. The Wall Street Journal, May 13, 2017, p. C6.

43. Letters Received by the Secretary of the Navy from Captains ("Captains' Letters") 1805-61; 1866-85, George W. Lee to Samuel Evans 23 Dec 1823, Volume 85, 8 Nov 1823 to 31 Dec 1823, Letter Number 113, Roll 0085,M125, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington DC.

During the inquiry, Commodore Renshaw’s acknowledgment of the list and his warning to Lee “Not to meddle in politics” gave credence to employee charges of favoritism and political patronage. If this was meant as a threat, Lee was not intimidated.

Renshaw: “Did I not shew to you a list of Heads of Departments, Clerks etc. that was sent to me shewing who was Whigs and Locofocos and was not your name amongst them and did I not say, I shew you this in order to guard against the possibility of you being brought before the Department by others outside of the Yard?”44

44. The Locofoco Party, was the radical wing of the Democratic Party organized in New York City in 1835. They were primarily made up of workingmen. In general, the Locofocos supported leaders like Andrew Jackson and Van Buren. They were for free trade, greater circulation of specie, legal protections for labor unions and against paper money, financial speculation, and state banks. Byrdsall, Fitzwilliam, History of the Loco-Foco or Equal Rights Party. (New York: Clement & Packard, 1842) pp. 13-14.

Lee: “Exhibit G was handed to me; he, the Commodore, did not show him a list but said to him that he had the list, and witness name [George W. Lee] was on it – “The Commodore said I was on the list as a Whig and advised me not to meddle with politics or something to the effect.”45

45. Renshaw Inquiry, pp. 107-109.

1841 Naval Court of Inquiry re James Renshaw, p.109: question by James Renshaw, answer of George W. LeeCommodore Renshaw’s Rebuttal

Commodore Renshaw provided the court a full and detailed rebuttal. The following paragraph is from his summation.

What has been established by the evidence before the court is, 1st. That in accordance with custom of my predecessors in command I have used at the house in the Yard, occupied by me, the Government coal. 2nd. That I have a gardener working in the garden & hot house attached, who is upon the Books as teamster. 3rd. That I have a man by the name of Muck who is upon the Books of the yard, as a Teamster, who goes to market & performs other friendly office for my family in the intervals of the remainder of his Duties. 4th. That the master joiner has made for me a new chair to replace one in the Commodores Office, removed by Commodore Ridgley and that I gave the necessary requisition upon the naval storekeeper for the materials to make it. Also, 5th. I ordered new oil cloths to replace old ones in the basement entry of my house which were worn out. 6th. That I caused three 2nd-hand carpets to be removed from the public store and put in different parts of the house, one of which had been since [illegible] another has been condemned as unfit for service, and the other has not ever been on the Books of the Yard as public property. 7th. That I took 3 buckets of molasses, 5 or 6 of common salt, for packing together with some scrubbing dust & other brushes, all of which were public property. 8th. That a few gallons of oil has been sent to my house for that purpose by the master of the yard. 9th. That I have employed an additional clerk in my office to assist in the duties. 10th. That like my predecessors in command I have employed the public carts to haul wood & coal in my house and manure to the public ground. 11th. That I have replaced a hot house belonging alike to the government, which was incapable of repairs. 12th. That I took two boxes of candles from the ordinary of the yard on the occasion of the fete given to the Arabian Ship by the express command of the Government. 13th. That I have employed the public plumber to make kitchen furniture in the house, to replace and repair that which had been there before, all of which was necessary for kitchen purposes. 14th. That I had borrowed money of Mr. Patterson, which I could not pay at the time but which I am now returning by monthly installments.46

46. Renshaw Inquiry, pp. 264-267.

Commodore Renfrew then added a refutation of the charge that he was a partisan of the Democratic Party.

Upon my first assuming command of this Station, various rumors and reports reached me to the effect that my appointment was sought for & granted at the request of the Democratic party here – Upon which grounds and reports were circulated I must confess I am at a loss to conceive, as I most assuredly gave to no party cause by word or deed to believe for one moment that I would lend my influence, or prostitute my command for political purposes.47

47. Renshaw Inquiry, p. 276.

The Board of Inquiry Concludes

Despite this, the court found against Renshaw. On 28 June 1841, after reading the grim final report of the Board of Inquiry, a distressed and hurt Commodore Renshaw wrote to Secretary of the Navy George E. Badger, “That great, very great injustice has been done me by the findings of the Court… which my removal from the Navy Yard has inflicted upon my reputation and interest…”48 Commodore Renshaw was correct that his fate before the Court of Inquiry was a topic of speculation, both in the Brooklyn Navy Yard and in various national newspapers in the Spring of 1841.49

48. Letter Received by the Secretary of the Navy from Captains, (Captains Letters) 1805 -1861, Renshaw to Badger, 28 June 1841, 1 June 1841 to 30 June 1841, Volume 278, Letter 145, p. 1, Roll 0278, RG 260, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington DC.

49. New York Evening Express (New York, New York, 1841), p. 3, Philadelphia Public Ledger (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1841), p., New Bedford Register, (New Bedford, MA, 1841), p. 13.

Replacing Renshaw was the new commandant of the Brooklyn Navy Yard and rising star Commodore Matthew C. Perry, who wrote Secretary Badger that he had assumed command and assured him, “My stated aim will be to bring the command entrusted to me into a superior state of discipline and efficiency.”50

50. Letter Received by the Secretary of the Navy from Captains, (Captains Letters) 1805 -1861, Perry to Badger, * 28 June 1841, 1 June 1841 to 30 June 1841, Volume 278, Letter 146, p. 1, Roll 0278, RG 260, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington DC. * Matthew Perry’s letter of 28 June 1841, was mistakenly filed as that of William Sears of the same date.

In June 1841, following Commodore Matthew Perry’s assumption of command at Brooklyn Navy Yard, Commodore Renshaw visited Washington D.C. hoping “to induce Mr. Badger [Secretary of the Navy George E. Badger], to place me where I stood before in the eyes of the public…” However, nothing came of this interview as Secretary Badger was quickly replaced in a cabinet reshuffle by Abel P. Upshur in September 1841. A disappointed Renshaw then wrote Secretary Upshur, a Whig politician, pleading for “orders for the Command of the Home Squadron or by restoration to my later command of the Navy Yard at New York.” Renshaw continued describing how the inquiry was, “humiliating, heartless, unbending and truly painful … He concluded by again requesting “an order for my return to my late command…” and restating how the inquiry had caused “damage to my reputation as an officer and the anxiety under which I labor…” 51

51. Letter Received by the Secretary of the Navy from Captains, (Captains Letters) 1805 -1861, Renshaw to, A. P. Upshur, 10 October 1841, Volume 282, 1 Oct 1841 to 31 Oct 1841, Letter 78, pp.1-3. 1, Roll 0278, RG 260, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington DC

In spite of Commodore Renshaw pleas, Secretary of the Navy Upshur did not restore him to command of the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Instead Upshur chose to accept the verdict of the Naval Court of Inquiry and reassigned Renshaw to command the much smaller Charleston Navy Yard at Charleston, South Carolina.

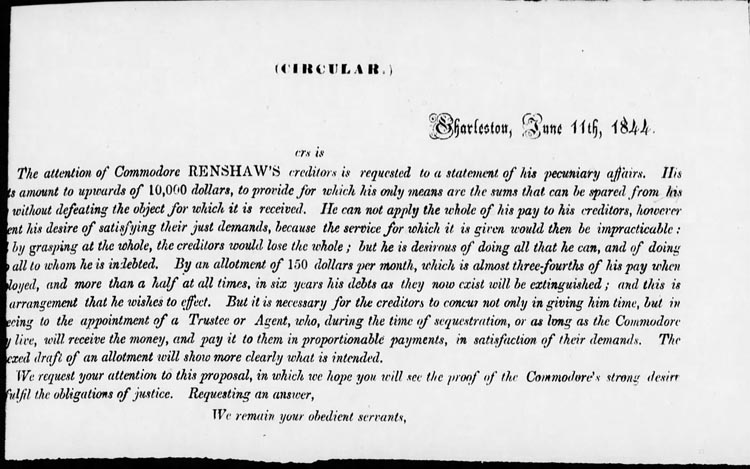

Commodore Renshaw Circular re debt dated 11 June 1844On 20 January 1843 Commodore James Renshaw married Charlotte Elizabeth Ganahl, a 43 year old widow in Chatham, Georgia. Whatever joy and solace this brought was short lived, for his creditors were relentless in their pursuit and continually harried him to make payment. In September 1844, he once again found himself in the “humiliating” position of writing Secretary of the Navy A.P. Upshur about “his pecuniary affairs” and enclosed the above circular which calculated his debt as of 11 June 1844, “to amount to upwards of $10,000.” 52

52. Letter Received by the Secretary of the Navy from Captains, (Captains Letters) 1805 -1861, Renshaw to A. P. Upshur, 3 September 1844, Volume 316, 2 Sept to 30 Sept Oct 1844, Letter 16, pp. 1-5, (circular, p. 5.), Roll 0316, RG 260, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington DC

On 28 May 1846 Commodore James Renfrew died. He was 62 years of age. He was buried in Congressional Cemetery, Washington, D.C. His wife Charlotte was pensioned 29 May 1846 at the rate of $50.00 per month. 53.

53. Commodore James Renshaw Find a Grave https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/91416785/james-renshaw

* * * * * *

John "Jack" G. M. Sharp resides in Concord, California. He worked for the United States Navy for thirty years as a civilian personnel officer. Among his many assignments were positions in Berlin, Germany, where in 1989 he was in East Berlin the day the infamous wall was opened. He later served as Human Resources Officer in South West Asia (Bahrain). On return to the United States in 2001, he was serving on duty at the Naval District of Washington on 9/11. He has a lifelong interest in history and has written extensively on the Washington, Norfolk and Pensacola Navy Yards, labor history and the history of African Americans. His previous books include African Americans in Slavery and Freedom on the Washington Navy Yard 1799-1865, Morgan Hannah Press 2011 and History of the Washington Navy Yard Civilian Workforce 1799-1962, 2004.

https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/browse-by-topic/heritage/washington-navy-yard/pdfs/WNY_History.pdf

and the first complete transcription of the Diary of Michael Shiner Relating to the History of the Washington Navy Yard, 1813-1869, 2007/2015 online:

https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/d/diary-of-michael-shiner.html

His most recent work includes “Register of Patients at Naval Hospital Washington DC 1814 With The Names of American Wounded From The Battle of Bladensburg” 2018,

https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/r/register-patients-naval-hospital-washington-dc-1814.htmlHe is currently working as a writer/adviser with Salt Marsh Productions, Animating History American Stories Brought to Life, in a production of “The Diary of Michael Shiner” set for release late 2022.

John served on active duty in the United States Navy, including Vietnam service. He received his BA and MA in History, with honors, from San Francisco State University. He can be reached at sharpjg@yahoo.com