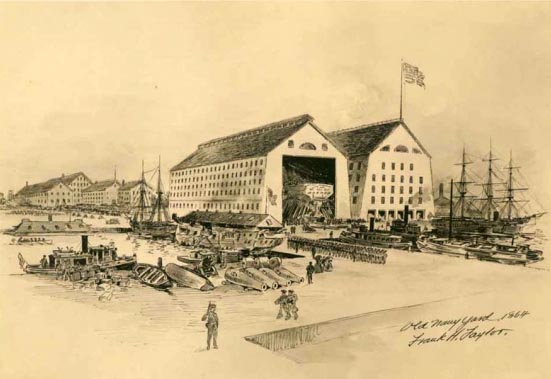

The Philadelphia Navy Yard in 1835

& the birth of the Ten-Hour Day

By John G. M. Sharp

At USGenWeb Archives

Copyright All right reserved

Construction of frigate USS Philadelphia in November 1798, William Birch

Introduction: To the City of Philadelphia, the Philadelphia Navy Yard and it hard working mechanics and laborers, belongs the credit, for the first instance of action that significantly improved the lot of federal shipyard workers, the ten-hour day. This achievement was a Naval Regulation signed by Commodore John Rodgers Head of the Board of Navy Commissioners (see document below) on 26 August 1835. This was distributed to all Navy, shipyards and shore installations. The Philadelphia Navy Yard shipwrights, joiners and other workers became leaders in this effort when they chose to combine direct action, a strike, with political pressure to the executive branch. After first making a request to the Secretary of the Navy via shipyard Commandant Commodore James Barron, on 29 August 1835 they appealed directly to President Andrew Jackson.1

1. John Crossin, William Thompson, Joshua L. Fletcher, Joseph D. Miller, and Edward McDonald to Andrew Jackson 29 August 1836, Special Collections, MS-3333, University of Tennessee, Libraries, Knoxville, Tennessee.

Background: In the early nineteenth century employers almost everywhere in the new nation successfully challenged strikes and work stoppages in the courts. Unions and strikes often constituted illegal conspiracies in common law and exposed labor union members to criminal prosecution. Indeed, many individual states banned labor associations as "injurious to public morality or trade or commerce."2 By 1834 most Philadelphia private sector shipyard workers persuaded employers to accept the ten-hour day – but the Department of the Navy was reluctant would not agree to any concessions.3 For mechanics and laborers the twelve hour day was the norm with shipyard employees at Philadelphia working twelve hours a day, dawn to dusk. Despite legal impediments though, workers still held job actions, so called “turn outs” and struck employers, especially in the tremulous year of 1835, brought pressure to limit the work day to ten hours.4

2. Webb, Sidney; Webb, Beatrice, History of Trade Unionism, (Longmans and Co., London, 1920), chapter 1.

3. Harvey, O. L. “The 10-Hour Day in the Philadelphia Navy Yard, 1835-36.” Monthly Labor Review, vol. 85, no. 3, Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, 1962, pp. 258–60,

http://www.jstor.org/stable/41834722p4. Sharp, John G.M.,The Washington Navy Yard Strike and Snow Riot of 1835,

http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/washingtonsy.htmlFederal Shipyard Workers: Shipyard workers were in law and in fact day laborers, and paid a per diem wage only for days actually worked. Theirs was a life where the only certainties were often hard and unpleasant. A cold winter usually led to mass layoffs as only the most essential crews would be kept working. No compensation was available for on the job injuries, illness too often meant dismissal. “When illness struck a journeyman craftsman, his body could fail, but more importantly his ability to provide for his family failed. Preventive medicine was not much of an option for working men and whether it was a minor flu or a periodic cholera outbreak, some illness eventually caught up with them.”5

5. Greenburg, Joshua R., Advocating the Man, Masculinity, Organized Labor, and the Household in New York, 1800-1840 , Trade Unions, p. 9,

http://www.gutenberg-e.org/greenberg/print/Chapter5JRG.pdfIn 1835 the United States had no civil service, all federal manual and craft workers, were per diem employees, appointed and fired at will. Retirement in the 1830’s was still a dream for most Americans. Retirement for federal workers, would finally become a reality with the creation of the modern civil service retirement system in 1920.6 Patronage and nepotism in the 1830’s were legal and wide spread. Testing and competitive appointments to federal jobs via competition were unknown and would only become law in 1882 with the passage of the Pendleton Act.7

6. Sharp, John G., History of the Washington Navy Yard Civilian Workforce, 1799-1962, (Naval District Washington, Washington DC, 2005), p. 55,

https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/browse-by-topic/heritage/washington-navy-yard/pdfs/WNY_History.pdf7. Sharp, John G. History of the Washington Navy Yard Civilian Workforce 1799 -1962, Naval History and Heritage Command 2005, p.42,

https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/browse-by-topic/heritage/washington-navy-yard/pdfs/WNY_History.pdfFewer naval ships to repair invariably meant fewer mechanics and laborers on the Navy Yard payrolls. These conditions, and especially any cutbacks in annual naval appropriations, made the workforce particularly vulnerable to economic downturn, a wage reduction and or prolonged unemployment, which rapidly led the men to destitution. Most shipyard workers had little savings on which to fall back on and imprisonment for debt was a daily reality experienced by thousands of the city’s workers each year.

In the decade of the 1830’s workers, particularly in Philadelphia, Boston, New York City, and Washington D.C. petitioned for higher wages, better working conditions, and a ten-hour workday. In the “City of Brotherly Love”, the 1835 Philadelphia General Strike was the culmination of rising discontent with both wages and hours of work. Workers held meetings to build support and “to adopt measures to bring about concentrated action on the part of mechanics and laborers to establish the ten-hour system.”8 The well-organized and planned strike, took place from 6 June to 25 June 1835.9 The short-lived General Trades’ Union (GTU) of the City and County of Philadelphia the citywide demand for a ten-hour workday. Their successful action set a precedent followed by other labor organizations in the nation later in the nineteenth century.10 This was the first general strike in North America and involved some 20,000 workers who struck for a ten-hour workday and increased wages. The strike ended in complete victory for the workers.11

8. Philadelphia Inquirer (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), 5 June 1835, p. 2.

9. The planning is evident, for instance in the Cordwainders ,(shoe makers) resolution to “form a committee of three be appointed to contradict those statements which may be made by employers or others relative to an immediate strike United States Gazette, (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), 6 May 1835, p. 4.

10. Grubbs, Patrick, “The General Trades Union Strike of 1835”, The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia,

https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/general-trades-union-strike-1835/11. Foner, Philip S., History of the Labor Movement in the United States, Vol. 1, From Colonial Times to the Founding of The American Federation of Labor, (International Publishers, 1975), pp. 116–118.

For much of the nineteenth century Federal shipyard workers had a precarious economic and employment status. Their wages were subject to considerable change, in some cases daily pay fluctuated dramatically, e.g. carpenters wages at Washington Navy Yard were reduced from a high of $2.50 per day in the year 1808 to $1.64 per day in 1820.12 Walkouts or strikes such as one that occurred in Gosport (Norfolk) Navy Yard on 19 June 1834, when the ship carpenters attempted to strike for higher wages which often resulted in their dismissal.13

12. Tingey to Board of Navy Commissioners, 9 January 1821 National Archives and Records Administration, Washington DC, RG 45, Entry 314, Volume 74.

13. Sharp, John G.M., Gosport Navy Yard Carpenters 1834,

http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/nnysharp2.html#carpenters

Philadelphia’s Moyamensing Prison 1838These conditions, and especially any cutbacks in annual naval appropriations, made the workforce particularly vulnerable to economic downturn, a wage reduction and or prolonged unemployment, which rapidly led the men to destitution.7 Shipyard workers, had little savings on which to fall back on and imprisonment for debt was a daily reality experienced by thousands each year. Falling into debt was a serious matter, Philadelphia’s Moyamensing Prison, located at Tenth and Reed Streets was built in 1832 -1835 even had a special “Debtor’s Apartment, or Debtor’s Wing.”14 The state of Pennsylvania would only abolish imprisonment for debt in 1842.15 The two letters below are from Commodore James Barron, Commandant of the Philadelphia Naval Yard.16 Commodore Barron wrote to the Board of Navy Commissioners and described his attempts to resolve demands from the shipwrights for change in working hours.17, 18

14. Philadelphia County Prison, (PDF)National Parks Service 1984,

https://web.archive.org/web/20170224063030/http://cdn.loc.gov/master/pnp/habshaer/pa/pa1000/pa1056/data/pa1056data.pdf15. Asa Earl Martin, Hiram Herr Shenk, Pennsylvania History Told by Contemporaries, (Macmillan, New York, 1925), p. 365,

https://books.google.com/books?id=Yqd4AAAAMAAJ&pg=PA365&dq=history+of+imprisonment+for+debt+in+philadelphia&hl= en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiq5fvC8MX1AhWrm2oFHc-MDCcQ6AF6BAgKEAI#v=onepage&q=history%20of%20imprisonment%20for%20debt%20in%20philadelphia&f=false16. Barron, James. Lieutenant, 9 March, 1798. Captain, 22 May, 1799. Died 21 April, 1851, Officers of the Continental and U.S. Navy and Marine Corps 1775-1900, Naval History and Heritage Command, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-

alphabetically/o/officers-continental-usnavy-mc-1775-1900/navy-officers-1798-1900-b.html17. Navy Board of Commissioners, Letters Receive, National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 45, E314, Volume 91.

18. Sharp, John G., Philadelphia Pennsylvania Biographies,

http, genealogytrails.com/penn/philadelphia/phlbios_a-b.html

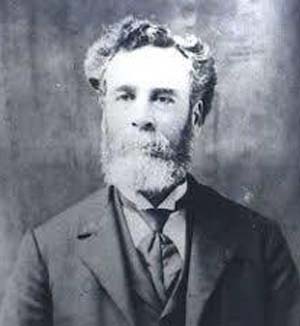

Commodore James BarronCommodore James Barron (1768-1851) had served in the Quasi-War and the Barbary Wars, in which he commanded a number of famous ships, including the USS Essex and the USS President. Barron had begun his service in 1798 and by 1835 was one of the most senior naval officers. However some missteps early on in his career had damaged his reputation and strained his relationships with some officers. As commander of the frigate USSChesapeake, he was court-martialed for his actions in 1807, which led to the surrender of his ship to the British. After criticism from some fellow officers, the resulting controversy led Barron to a duel with Stephen Decatur, one of the officers who presided over his court-martial. Suspended from command, he pursued commercial interests in Europe during the War of 1812. Barron traveled extensively in Northern Europe including the Kingdom of Denmark, (26 January 1828) where he observed the poppy fields.Barron finished his naval career on shore duty, becoming the Navy's senior officer in 1839. Barron was commandant of the Gosport Navy Yard from 1825-1831. His letters from Gosport Navy Yard reflect a conscientious and capable manager with considerable experience working with civilians.19He also had an interest in nautical science and even submitted a detailed plan for new dry dock to the Secretary of the Navy Samuel Southard on 21 July 1826.His “Achilles heel” as prominent naval historian Christopher McKee summarized it was “Barron’s actions in the Chesapeake –Leopard incident of 1807 inflicted a mortal wound on his professional reputation. He carried with him the seeds of his own downfall. A man of repeatedly proven bravery in the face of danger, he was also prey to deep pessimism that could reduce him to inaction at critical junctures when an ambiguous situation demanded moral rather than physical courage.”20Barron was commanding officer of the Philadelphia Navy Yard from 7 March 1831 to 1837.

19. Sharp, John G.M., Letters from and to the Gosport Navy Yard 1826-1828,

http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/nnysharp14.html20. McKee, Christopher, A Gentlemanly and Honorable Profession the Creation of the U.S. Naval Officer Corps, 1794-1815 (Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, 1991), p. 336.

The working day at Philadelphia Naval Yard in the summer of 1835, was officially from sun rise to sun set with forty five minutes for breakfast at 7.00 A.M. and an hour at 1.00 P.M., for lunch. Agitation for the ten-hour day in Philadelphia in the 1830’s and reached a peak in 1834/35.21 The Philadelphia Navy Yard shipwrights wanted Barron and the Department of the Navy to shorten the workday from 12 to 10 hours. Like many naval officers ashore Barron had to learn the fine art of administering a large civilian workforce. In April 1834 he wrote to the Secretary of the Navy Levi Woodbury, requesting a copy of the “Rules of the Navy Department, Regulating the Civil Administration.”22

21. Sparrough , Michael E., “Historical Underpinnings of the Federal Labor Relations System for Non-uniformed Employees”, Unionizing the Armed Forces, editors Ezra S. Kendal and Bernard L. Samoff, ( University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, 1977), p. 32-43.

22. James Barron to Levi Woodbury, 2 April 1834, Letters Received by the Secretary of the Navy by Captains, “Captains Letters”, Volume 193, 1 April 1834 to 30 April 1834, Letter Number 5, RG 260, NARA, Washington, DC.

From Barron’s letters it is apparent he was familiar with the growing demand for ten-hour day. The struggle for a shorter workday in the United States had begun in the late eighteenth century, even before the establishment of the first trade unions. For the workers a key aspect of the campaign concerned the way they framed their demand. Many argued that the ten-hour day was needed not only to protect the health of workers, but also because the long and exhausting workday was a barrier to more revolutionary change.

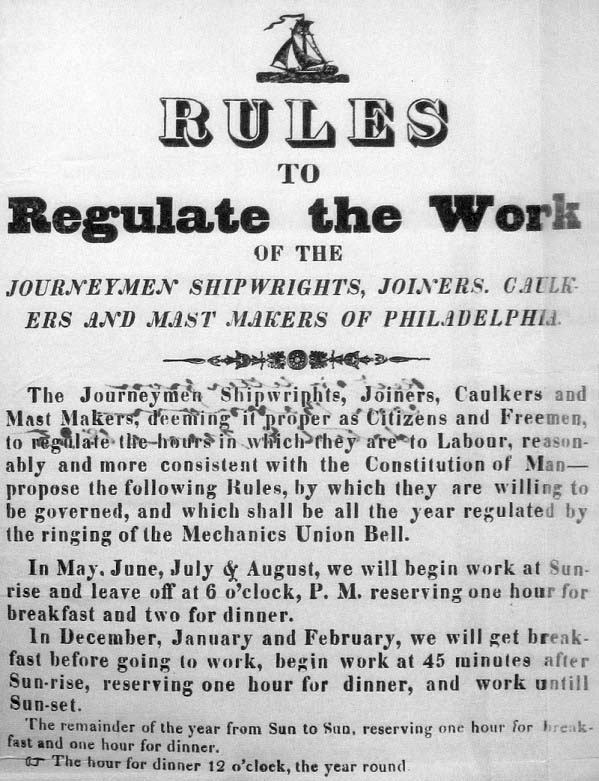

1835 Philadelphia shipyard workers circular for a ten-hour day

(double click to enlarge)A Tremulous Year: In 1835 labor discontent seemed to be everywhere. Boston carpenters had actually gone on strike for a ten-hour workday and were soon joined by masons and stone-cutters. The strikers chose Seth Luther and two other workers as leaders, and they issued a circular stating their demands for a ten hour day. During the strike, the Boston workers organized a travelling committee and requested the assistance of workers in other cities. The so called “Boston Circular” was well received by workers throughout the country. Although the Boston strike was eventually defeated, the circular was pivotal in motivating workers in Philadelphia to organize their own strike that year for a ten-hour workday. The president of the Carpenter's Society of Philadelphia, William Thompson, told Seth Luther that "the carpenters considered the Boston circular had broken their shackles, loosened their chains, and made them free from the galling yoke of excessive labor."23

23. Bernstein, Leonard "The Working People of Philadelphia from Colonial Times to the General Strike of 1835", Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 30 June 1950, p. 339, https://journals.psu.edu/pmhb/article/view/30723/30478

Seth Luther (1795-1863) was a Delaware house carpenter who became a labor leader and workers' and suffrage organizer. In 1835 Luther quickly established himself as a charismatic leader of the ten-hour movement. In a widely read speech he exclaimed, to his audience, “It is the first duty of an American citizen to hate injustice in all its forms; then he we be prepared to do justly, love mercy, and walk as he ought to walk in the sight of God and Man”24

24. Molloy, Scott, “Peaceably if we can, forcibly if we must!” Rhode Island: The Rhode Island Labor History Society, 23 April 2013, http://www.rifuture.org/remember-seth-luther/

Seth LutherIn his speech to the House Carpenters and Stone Masons on 4 May 1835, declared;

We have been too long subjected to the odious, cruel, unjust and tyrannical system which compels the operative mechanic to exhaust his physical and mental powers. We have rights and duties to perform as American citizens and members of society, which forbid us to dispose of more than ten hours for a day’s work.”

Luther then reminded his listeners, that the employer’s opposition to the ten-hour day was based on their supposed concern that working people should not have too much leisure, less,

We spend all our hours of leisure in Drunkenness and Debauchery if the hours of labor are reduced…they employ us about eight months in a year during the longest hottest months and in the shortest days hundreds of us remain idle for want of work for three or four months when our expenses of course must be heaviest during the winter. No fear has been expressed by our benevolent employers respecting our morals during the shortest months... Further they threaten to starve us into submission to their will to keep us from getting drunk!25

25. Irving, Mark and Schwaab, Eugene L., The Faith of Our Fathers (Alfred E. Knopf, New York, 1952), pp. 342-343.

During the summer of 1835 a “Ten-Hour Day Circular” was issued by the Philadelphia journeymen shipwrights, joiners, caulkers and mast makers. Their circular titled “Rules to Regulate the Work of Journeymen Shipwrights, Joiners, Caulkers and Mast Makers” and boldly called for a reduction in working hours from twelve to ten hours per day. The authors then identified themselves as “citizens and freemen” and declared their proposed hours more consistent with the U.S. Constitution. They also specified their work hours be regulated not by foremen, but a “Mechanics Bell” so that all could be alerted to the time. In age when most workers could not afford to carry fragile timepieces, a large bell was installed in most shipyards served to ring the opening and close of the workday.

That year in the Philadelphia Navy Yard, workers still labored twelve per day, a system first approved in 1819.26 Commodore James Barron enclosed in his letter a copy of the workers circular for the Secretary of the Navy Mahlon Dickerson. Barron probably wanted to give Dickerson, some idea of what Department of the Navy and Jackson Administration faced in Philadelphian. From his letters it is clear Barron had read the document and was well aware that city labor leaders had widely distributed this same circular to other federal shipyards.

26. Harvey, p. 258.

Banner of the Journeymen House Carpenters, 1835The banner of the Journeymen House Carpenters at the top of this post was painted and used during the General strike. One carpenter taps another on the shoulder and points to the setting sun and the clock on Carpenter’s Hall. In the bottom right corner, “6 to 6” is written on one end of a tool chest.27

27. “From 6 to 6”, Lost Art Press , 2019, https://blog.lostartpress.com/2019/09/04/from-six-to-six/

John F. Stump: The Navy Yard mechanics and laborers of 1835, as federal employees; had no legal standing to question or negotiate their hours of work and or wages. Instead they wisely chose John F. Stump (1800-1882), to be the chairmen of their committee.28Stump was an ideal choice, for he was a prominent figure in both business and politics. More importantly he was member of the Philadelphia Democratic Party and known as strong supporter of President Andrew Jackson and Marin Van Buren. He was also a man with numerous contacts in Washington D.C.29 Since Philadelphia was one of the few large cities that did not require property ownership to vote, politicians like Stump, quickly gained a following among the working class

28. Philadelphia Inquirer, (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) ,10 February 1882, p.2.

29. American Sentinel, (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), 7 January 1835, p. 2.

Commodore John Rodgers: The workers initial attempt made to persuade the Navy Board of Commissioners, to change the shipyard working hours faltered. From his letters (see below) to the Navy Commissioners, Commodore Barron fully understood that attitudes in Philadelphia were shifting as city leaders and local politicians were supportive of the workers. Locally Barron was even perceived sympathetic to change and laboring to “induce the Navy Commissioners to adopt the ten-hour system in the Navy Yard…”30 However he was apparently concerned about getting out ahead of the Board of Navy Commissioners, composed of senior captains and led by Commodore John Rodgers (1772-1838) who believed strongly in the chain of command. Rodgers and Barron though shared a long standing mutual antipathy which made their communication difficult. This all dated from the fatal 1822 duel in which Barron had killed Commodore Stephen Decatur, a close friend of Rodgers.31

30. United States Gazette (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), 28 August 1836, p.4

31. Schroeder, John H., Commodore John Rodgers Paragon of the Early American Navy, (University Press of Florida, Gainesville, 2006), pp 157-159.

Commodore John RodgersFairly quickly the Philadelphia Navy Yard workers came to see the Board of Navy Commissioners, especially John Rodgers as obstacle to further progress and with Stump’s help, drafted a memorial to the Secretary of the Navy to remove the power to set wages and hours from the hands of “petty tyrants of the Board.”32, 33 On 8 July 1835 Barron, recommended the Department of Navy, accede to the workers' demands, he wrote, "...the demands of the Mechanics are but a voluntary act of the Board [of Navy Commissioners] which can involve no unpleasant feelings and which in my opinion - I would respectfully observe this Seems to be inevitable, sooner or later, for as the working man are seconded by all the Master workmen, city councils etc. there is no probability they will secede from their demands"34 “By August of 1835, Secretary of the Navy Dickerson admitted “that ten hours of labor in a Navy Yard should be considered a day’s work.”35 After which, on August 26, 1835 Commodore Rodgers, signed a circular (see transcribed document below) which was transmitted to all Naval Yard establishing the new workday as ten hours.

32. This rare surviving copy of the 1835 Philadelphia circular was found in the National Archives and Records Administration, with the letters of Commodore James Barron, NARA, Washington DC Board of Navy Commissioners, Letters Receive, RG 45, E314 Volume 91.

33. Roediger, David E and Foner, Phillip S., In Our Own Time A History of American Labor and Working Day (Greenwood Press: Westport, 1989), p. 39.

34. Harvey, an>

35. Roediger, p. 39.

The workers successful job action had led to major changes in federal labor policy and the gradual transformation of the federal workday from 12 hours to 10. On 31 1840 the ten-hour day was finally codified into federal regulation by President Martin Van Buren. Van Buren’s ten-hour day executive order covered employees in all agencies (see document below) that performed manual work.36

36. Roediger, p. 40.

The Philadelphia Navy Yard employees were successful. They deserve to be remembered, their achievement was no small feat for against long odds, and they had successfully, organized, lobbied politicians and won public support. The result was a substantial victory, the first instance of action by the federal government which reduced the hours employees labored and with no reduction in their wages.37, 38 By the end of year 1835, most mechanics and laborers were working a ten-hour day in Philadelphia.

37. Personnel Literature, Volume XXI, number 1., Jan 1962, ( United States Civil Service Commission, Washington D.C., 1962), p. 15.

38. Harvey, O. L. “The 10-Hour Day in the Philadelphia Navy Yard, 1835-36.” Monthly Labor Review, vol. 85, no. 3, Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, 1962, pp. 258-60, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41834722.

John G M Sharp, 23 January 2022

* * * * * * * * * *

Comdt’s Office

U.S. Navy Yard,

Philad. 8th July 1835Sir,

The Mechanics in this city of all denominations have recently made, as it is termed, a turnout, for a regulation in the hours of labor, and so general is the feeling amongst the respectable portion of the community that the Master mechanics, City councils and County and district Commissioners have all conceded to them the terms demanded say from 6 o’clock to 6 o’clock, during those months of the year when the Sun rises before & sets before or at 6 clock, allowing one hours for dinner, and from Sun rise till Sun set, for all the balance of the year granting the same time for meals.

The Shipwrights, differ in some respects with regard to the time they are willing to work, and I here with enclose to the Board a copy of the rules by which their working hours are regulated from the Symptoms which have developed in the body since the hours from 6 to 6 have been granted to the other mechanics it is evident however that these rules will not be adhered to long and that the same terms will be demanded by the Shipwrights - This therefore would seem to me to be a favorable moment to adopt the hours from the 6 to 6 - in the Yard provided the Board should think proper to do so for as that would not be a concession on the part of the Commissioners to the demands of the Mechanics but a voluntary act of the Board which can involve no unpleasant feelings and which in my opinion - I would respectfully observe this Seems to be inevitable, sooner or later, for as the working man are seconded by all the Master workmen, city councils etc. there is no probability they will secede from their demands

I am Very respectfully Your Obedient Servant

James Barron

[Addressed to]

Commodores

Isaac Chauncey

Charles Morris* * * * * * * * * *

Commanding Officer

U.S. Navy Yard, Phila

9th July 1835Sir,

The conversation which I had with you on Sunday last induced me to believe that if any arrangements could be made with the workmen of this city to perform their labor by the hour, it would be agreeable to the Board of Navy Commissioners, so to employ them.

In consequence of the conversation, above alluded to, I sent for one of the workmen and requested him to consult with his friends, and endeavor to ascertain their ideas on the subject, communicating to me the result, so soon as known to him and it is therefore probable that early in the next week , I may receive this information.

I have therefore, to request any instruction or opinion from the Board that it may have to give, relative to the latitude which it may think proper to invest me with.

The wages are about two dollars per diem or twenty cents per hour.

I am Sir very respectfully

Your Obedient Servant

James Barron

[Addressed to]

Commodore John Rodgers

President Board of Navy Comm.

Washington* * * * * * * * * *

The Ten Hour Day,

Philadelphia Inquirer,

Philadelphia, 20 July 1835, p.2

A public meeting of the Shipwrights, Caulkers, Riggers and others connected with the art of shipbuilding, was held at the Commissioners Hall, Southwark on the evening of Friday last the object of the meeting being to hear and act upon a letter received a day or two since from the Secretary of the Navy. John F. Stump, Esquire was present, and made quiet an appropriate address on the occasion. It appears that some months since the shipwrights, carpenters, riggers, and others connected with the various shipyards of Philadelphia made an appeal to the Master Builders, who cheerfully agreed to consider ten hours as the Working Day. A short time after an order was received from Washington authorizing a store ship to be built at the Philadelphia Navy Yard, and a number of hands were immediately advertised for. It was soon ascertained, however that they were expected to engage themselves in conformity with the terms of the old arrangement. They refused and the work was consequently delayed. Mr. Stump accidently hearing of the circumstance, advised the shipwrights to detail the whole matter to the Secretary of the Navy. This was accordingly done, the letter signed by Messrs. Stump, Page and Horn. The result was of the most satisfactory character. The Secretary promptly responded to the letter, and remarked that it would be perfectly agreeable to the Department that the shipwrights engaged on the public work should not be compelled to labour longer than those engaged in the private shipyards. The letter was read at the meeting on Friday night and received with every proper demonstration of satisfaction. A committee was appointed to wait upon Commodore Barron and another to forward a letter of thanks to Washington. The meeting was quite large and those present conducted themselves with due propriety.39, 4039. Philadelphia Inquirer, Philadelphia, 20 July 1835, p. 3.

40. Army and Navy Chronicle, Volume 1, (B. Homans, Washington, D.C.,1835),p.243, https://books.google.com/books?id=JnFMAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA243&lpg=PA243&dq=john+f.+stump+shipwright+

philadelphia+navy+yard&source=bl&ots=cDAj3Meryf&sig=ACfU3U1hc2RAwr31fDXIdLZTIbrstQg_Ag&hl=en&sa=

X&ved=2ahUKEwjcmIqfgMH1AhX8l2oFHahrAD0Q6AF6BAgQEAM#v=onepage&q=john%20f.%20stump%20shipwright %20philadelphia%20navy%20yard&f=false* * * * * * * * * *

Navy Circular, 26 August 1835

To: Commodore James Barron, upon the subject of the working hours established by the circular of this date Wednesday 26th Aug. 1835 [Board of Navy Commissioners] Circulars to Commandants: Wm. M. Crane, John Downes, Ch. Ridgeley, James Barron, Isaac Hull, L. Warrington & W. Chauncey. By Circular of this date, established the working hours of mechanics in different Navy Yards

Memoranda basis of Working Hours

Memoranda: Length of Days at Washington

January 1st 9h 20m January 15th 9. 34 February 1 st 10.00 February 15th 10.36 March 1 st 11.10 March 15th 11.46 April 1 st 12.20 April 15th 13.04 May 1 st 13.40 May 15th 14.10 June 1 st 14.32 June 15th 14.42 July 1 st 14.32 July 15th 14.28 August 1 14.02 August 15th 13.34 September 1 12.54 September 15th 12.20 October 1 st 11.40 October 15th 11.04 November 1 st 10.24 November 15th 9.54 December 1 st 9.28 December 15th 9.18 November, December, January & February: to commence work 45 minutes after Sunrise & have one hour to dinner will leave as a mean 8:05 for labor between Sunrise & Sunset. March to 15th April & Sept to end of October, an hour to breakfast & an hour to dinner, gives 9:47 for working time.

From 15th April to end of May & from 15 Aug to 15 Sept, an hour to breakfast & hour to dinner, will give 11:28 for working time.

June & July & half August, one hour for breakfast & 2 hours for dinner, gives 11:29 for the working hours.

The mean of the working hours for the year will be 9:53 for Washington.* * * * * * * * * *

Michael Shiner’s Diary re the Ten-Hour Day

In 1840 Michael Shiner, (1805-1880), a former enslaved labor and later as a freedman, a painter at the Washington Navy Yard, wrote this moving tribute in his diary to the Ten Hour Day and President Martin Van Buren.41The Working class of people of the united States Mechanic and laboures ought to never forget the Hon ex-president Van Buran for the Ten hour system for when they youster have to work in the Hot Broiling sun from sun to sun when they were Building the Treasure office before he gave the time from six to 6 the laborer youster have to go there and get the bricks and Mortar up on the scaffold before the Masons come untel the president ishurd [issued] a proclamation that all the Mechanics and laborers that where employed By the day By the federal government should Work the ten-hour Sistom from six to six i think and May the lord Bless Mr. Van Buran it seems like they have forgot Mr. Van Buran name it ought to be Recorded in every Working Man heart

41. The Diary of Michael Shiner Relating to the History of the Washington Navy Yard 1813-1869, Transcribed with Introduction and Notes by John G. Sharp (2007 and 2015) Naval History and Heritage Command, Washington, D.C.,

https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/d/diary-of-michael-shiner/1831-1839.html#77President Martin Van Buren, Executive Order, On 31 March 1840, President Martin Van Buren, by Executive Order, codified the changed work hours in all federal installations where employees did manual labor, from 12 to 10 per day. The order also made clear there would be no corresponding reduction in wages.42 The order as implemented on the Washington Navy Yard stated:

"By Direction of the President of the United States all public establishments will hereafter be regulated as to working hours by the "ten-hour System". The hours for labor in this Yard will therefore be as follows viz: From the 1st day of April to the 30th day of September inclusive from 6 o'clock a.m. to 6 o'clock p.m. -- during this period the workmen will breakfast before going to work for which purpose the bell will be rung and the first muster held at 7 o'clock -- at 12 o'clock noon the bell will be rung and then home from 12 to 1 o'clock p.m. allowed for dinner from which to 6 o'clock p.m. will constitute the last half of the day.

42. Roediger, p. 40.

From the 1st day of October to the 31st day of March the working hours will be from the rising to the setting of the Sun -- the Bell will then be rung at one hour after Sunrise that hour being allowed for breakfast -- at 12 o'clock noon the bell will again be rung and one hour allowed for dinner from which time say 1 o'clock till sundown will constitute the last half of the day. No quarters of days will be allowed."

The Philadelphia Navy Yard mechanics, to President Andrew Jackson, 29 August 1836

Despite the gains the Philadelphia shipyard mechanics and laborers made in 1835, there were still unresolved issues regarding the implementation of the ten hour work day.

Launch of the USS Pennsylvania at Philadelphia Navy Yard 18 July 1837

Library of CongressPhil Aug 29, 183643

To the President of the United States

Genl Andrew JacksonSir, permit the undersigned a Committee appointed at the town hall meeting of their fellow Citizens to address you on the subject of the utmost imtives of working men and it is a portion of their authority to solicit your interference on a subject of general complaint by all classes of working men in Philadelphia.

It may be unknown to you Sir that frequent appeals haveportance to them in many points of view, namely the recognition of the ten hour system in our National Navy Yard in Philadelphia – Your petitioners Sir, are laboring Mechanic’s and representa been made for the system establishment of a system requiring but ten hours labor in our national yard, the commandant has been solicited, the board of navy commissioners have been solicited, the Secretary of the Navy directives interference, Congress at last session was petitioned but none of these have availed and therefor a last resort the Committee has been appointed to solicit the fountain head of Government to acknowledge and require but ten hours labour on the Public Works in Phila Your petitioners conceive this an act of Justice that has been withheld detrimental to their interest nor would they ask it of the Government was not the system universal in Philadelphia the city and a county authorities require but ten hours labour for a day’s work, every shipyard in Philadelphia requires but ten hours labour and the Committee therefore have a well-grounded hope the Government will follow the example. Your petitioners would not urge the measure, were it not necessary from motives of self-defense. Orders have lately been given to finish the ship of the line Pennsylvania and although the navy commissioners (if they be the responsible power) will not accede to the demands of the laboring community they offer much higher wages than demanded in order to induce distant workmen to supersede our own mechanics and introduce and innovation of their rules.44 The numbers of workmen in Philadelphia are sufficient at former prices and all they ask of them our Government is not to expect more than is required in the [illegible] Merchant service. The Committee are sure that if the example is set in Philadelphia it will be [illegible] required in other places and they will not attempt to disguise the pleasure it would give them as Citizens and as Workingmen to see a reformation taking place under the auspices of the Government every other [illegible] in society is undergoing changes and if the Government refuses to avail the poorest but most powerful class we respectfully ask that they shall hold out no bonuses in the form of higher wages and undermine rules we have established for our salvation.

We desire to speak our minds plainly as Citizens without censuring any arm of the government they perhaps are not aware of the urgency of the case, false representations may have been made therefore we servants of the working men of Philadelphia are required to ask for the establishment of a reformed system of labor. The Country at this time is in a prosperous condition, the public coffers are overflowing. The number of laborers in the field are abundant and emigration is still increasing them with these facts it must be apparent that the happiness and prosperity of the people will be advanced by the adoption to grant more mental improvements or reduce the beastly quantity of labour required of them now. It will also be a gratification when you have retired from your official duties into privacy to reflect, that one of the last acts of your Presidential career was to give comparative freedom to millions of your countrymen and to know that the honest blessing of the Laborers will be awarded to your memory when you shall pass on to that home from whence no travelers return.

With sentiments of profound respect we remain your obedient servants and fellow Citizens

[The] Committee

John Crossin 10 Dean Street

Wm Thompson

Joshua S Fletcher

Joseph D Miller

Edward Mc DonaldAn answer is most respectfully requested JC

43. John Crossin, William Thompson, Joshua L. Fletcher, Joseph D. Miller, and Edward McDonald to Andrew Jackson, 29 August 1836, Special Collections Library, MS-3333, University of Tennessee, Libraries, Knoxville, Tennessee

44. USS Pennsylvania was a three-decked ship of the line of the United States Navy, rated at 130 guns, and named for the state of Pennsylvania. She was the largest United States sailing warship ever built, the equivalent of a first-rate of the British Royal Navy. Authorized in 1816 and launched in 1837, her only cruise was a single trip from Delaware Bay through Chesapeake Bay to the Norfolk Navy Yard. The ship became a receiving ship, and during the Civil War was destroyed.

* * * * * *

Michael Shiner, Diary, re the Ten Hour Day 45

In 1840 Michael Shiner, (1805-1880), a former enslaved laborer who later worked as a freedman, a painter at the Washington Navy Yard, wrote this moving tribute to the Ten Hour Day and President Martin Van Buren.The Working class of people of the united States Mechanic and laboures ought to never forget the Hon ex-president Van Buran for the Ten hour system for when they youster have to work in the Hot Broiling sun from sun to sun when they were Building the Treasure office before he gave the time from six to 6 the laborer youster have to go there and get the bricks and Mortar up on the scaffold before the Masons come untel the president ishurd [issued] a proclamation that all the Mechanics and laborers that where employed By the day By the federal government should Work the ten hour Sistom from six to six i think and May the lord Bless Mr. Van Buran it seems like they have forgot Mr. Van Buran name it ought to be Recorded in every Working Man heart.

45. The Diary of Michael Shiner Relating to the History of the Washington Navy Yard 1813-1869, Transcribed with Introduction and Notes by John G. Sharp (2007 and 2015) Naval History and Heritage Command, Washington, D.C.,https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/d/diary-of-michael-shiner/1831-1839.html#77

President Martin Van Buren, Executive Order, 31 March 1840

Andrew Jackson’s successor, President Martin Van Buren, by Executive Order, codified the changed work hours so that they applied to all federal installations where employees performed manual labor, and changed the day from 12 to 10 hours per day. This order also made clear there would be no corresponding reduction in wages.46 For example the order as implemented on the Washington Navy Yard stated:"By Direction of the President of the United States all public establishments will hereafter be regulated as to working hours by the "ten hour System". The hours for labor in this Yard will therefore be as follows viz: From the 1st day of April to the 30th day of September inclusive from 6 o'clock a.m. to 6 o'clock p.m. -- during this period the workmen will breakfast before going to work for which purpose the bell will be rung and the first muster held at 7 o'clock -- at 12 o'clock noon the bell will be rung and then home from 12 to 1 o'clock p.m. allowed for dinner from which to 6 o'clock p.m. will constitute the last half of the day.

From the 1st day of October to the 31st day of March the working hours will be from the rising to the setting of the Sun -- the Bell will then be rung at one hour after Sunrise that hour being allowed for breakfast -- at 12 o'clock noon the bell will again be rung and one hour allowed for dinner from which time say 1 o'clock till sundown will constitute the last half of the day. No quarters of days will be allowed."

46. Roediger, p. 40.

* * * * * *

John "Jack" G. M. Sharp resides in Concord, California. He worked for the United States Navy for thirty years as a civilian personnel officer. Among his many assignments were positions in Berlin, Germany, where in 1989 he was in East Berlin the day the infamous wall was opened. He later served as Human Resources Officer in South West Asia (Bahrain). He returned to the United States in 2001 and was on duty at the Naval District of Washington on 9/11. He has a lifelong interest in history and has written extensively on the Washington, Norfolk and Pensacola Navy Yards, labor history and the history of African Americans. His previous books include African Americans in Slavery and Freedom on the Washington Navy Yard 1799 -1865, Morgan Hannah Press 2011 and History of the Washington Navy Yard Civilian Workforce 1799-1962, 2004.

https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/browse-by-topic/heritage/washington-navy-yard/pdfs/WNY_History.pdf

and the first complete transcription of the Diary of Michael Shiner Relating to the History of the Washington Navy Yard, 1813-1869, 2007/2015 online:

https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/d/diary-of-michael-hiner.html

His most recent work includes Register of Patients at Naval Hospital Washington DC 1814 With The Names of American Wounded From The Battle of Bladensburg 2018,

https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/r/register-patients-naval-hospital-washington-dc-1814.html

The last three works were all published by the Naval History and Heritage Command. John served on active duty in the United States Navy, including Vietnam service. He received his BA and MA in History from San Francisco State University. He can be reached at sharpjg@yahoo.com