NEWPORT NEWS, Va. — The day broke raw and rainy on the Virginia shore, but Howard Lowell of Freeport, Maine, braced himself against the biting wind and scanned the gray-blue waters of Hampton Roads. At that very moment, 150 years before and at this site, his great-great-great-grandfather, John Lorimer Worden, led the USS Monitor against the Confederate ship Virginia in a momentous clash of Civil War ironclads. The hours-long fight ended in an exhausting draw, but the face of naval warfare changed forever. It was the first time two ironclad ships had battled. "I feel a sense of awe," said Lowell, 58, on Friday morning." And as an American, I feel a tie to the history here." That history, commemorated here in gala festivities this weekend, extends to Boston.

The hulking warship Virginia was an iron-sheathed remake of the Union frigate Merrimack, which had been launched at the Charlestown Navy Yard in 1855. Worden's name, nearly forgotten now, is chiseled along with those of other US naval heroes on the frieze of the Boston Public Library, the last name in the last column on the library's Boylston Street wall.

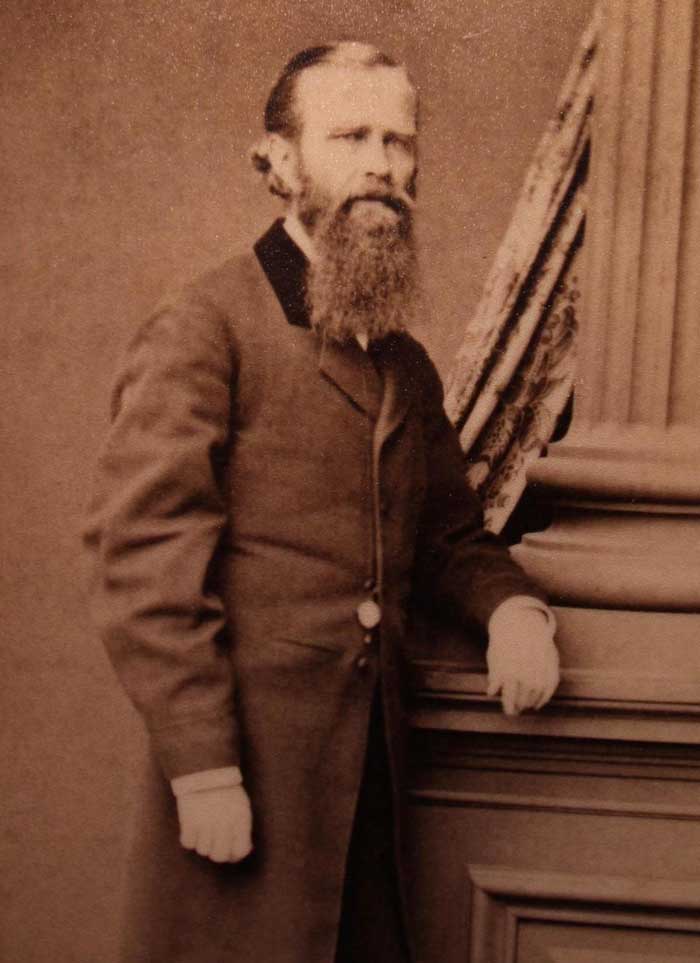

And after a century of being lost in a watery grave, one set of unidentified remains found on the Monitor could belong to a Boston sailor who drowned when the ship sank off North Carolina nine months after the battle. After painstaking forensic work and newly completed facial reconstruction, federal officials believe that one of two skeletons found in the Monitor's turret could be that of James Fenwick, a 24-year-old sailor from the North End. "It's down to two or three" candidates, said David Alberg, superintendent of the Monitor National Marine Sanctuary, where much of the wreck remains on the ocean floor. Two clay models of the reconstructed faces were first shown to the public Tuesday at the Navy Memorial in Washington. The younger of the two — its eyes calm and composed, its lines taut and defined — could be Fenwick, Alberg said. "We have created two faces that their mothers would recognize," Alberg said.

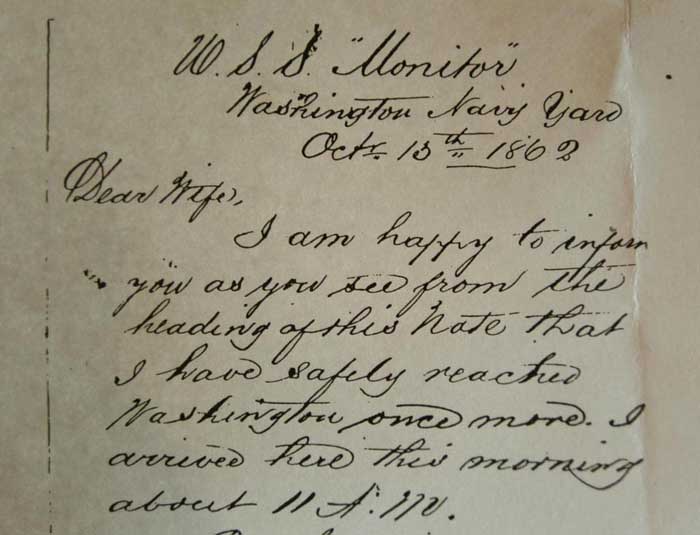

Fenwick's mother, however, might not have learned her son's fate for months, years — or, perhaps, not at all. A native of Scotland, Fenwick enlisted in Boston on July 23, 1861. While on furlough in October 1862, he married Mary Ann Duffy of 259 North St., but rushed back almost immediately to the Washington Navy Yard to rejoin his shipmates. Three days after his marriage, Fenwick wrote from Washington to tell his bride that he had returned too soon. The crew, as well as the paymaster, were still on furlough, he wrote. As a result, the $40 he had planned to send to Boston would have to wait. "Dear Wife," Fenwick wrote in impeccable penmanship, "I might have remained four days longer."

Displaying the faces could lead to a positive identification, Alberg said. The hope is that their lifelike shape will spark curiosity among descendants of Civil War veterans, prompt them to search family records, donate a DNA sample, and yield positive identification.

The government will be asked to bury the remains with military honors, possibly this year, at Arlington National Cemetery.

"These are men who are no different from men who were brought to Dover yesterday from Afghanistan," said Alberg, who paused to check his emotions. "It reminds you of how it's not over, how it still matters."

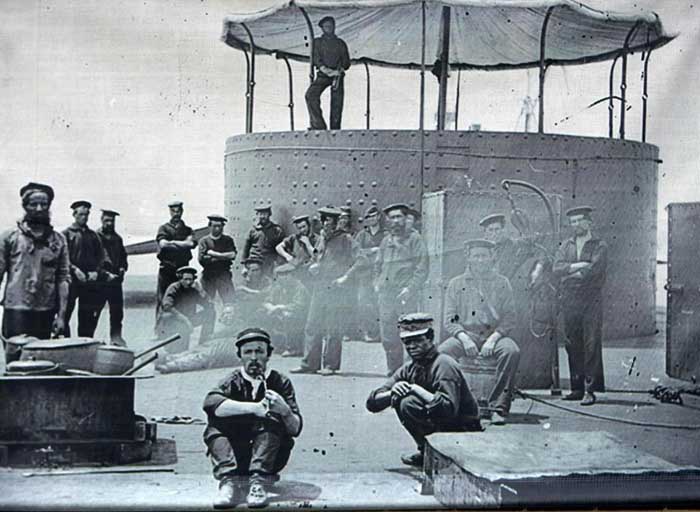

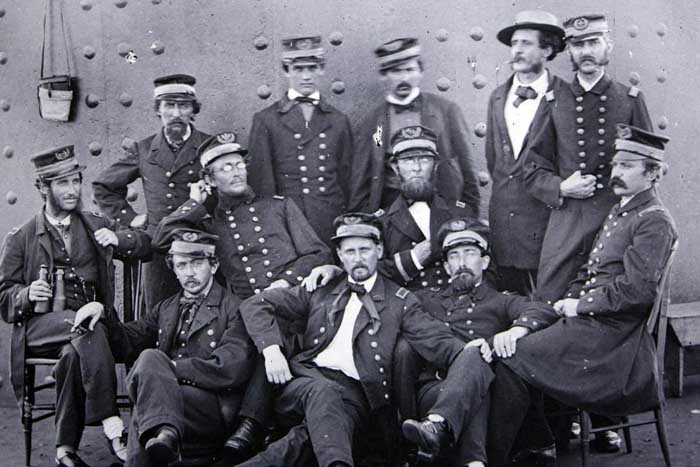

For most Americans, however, the saga of the Monitor and the Merrimack — the ship is more widely known by that name than the Virginia — is a vaguely remembered snippet from a long-ago history lesson. The construction of the Monitor, completed in only 98 days to counter the Merrimack, was the Civil War equivalent to the US-Soviet space race. Derided by some as a "cheesebox on a raft," the ship upended naval architecture with its 360-degree revolving turret and a deck that rode only 18 inches above the water.

For someone like Lowell, the descendant of the Monitor's captain, the 150th anniversary of the battle is a chance to reflect on history that helped define the country and its people. "It's important to look back and talk about what brings you to the present," said Lowell, who also is a direct descendant of the 19th century poet James Russell Lowell. "We don't do that. We're too busy at the mall."

That feeling is keenly felt in Arlington, Mass., too, where John Lorimer Worden III proudly hangs a portrait of his relative in his hallway. His great-grandfather, who was Worden's first cousin, named his son for the famous relative who was temporarily blinded in the battle, promoted to rear admiral, and served as superintendent of the US Naval Academy. A succession of namesakes followed, continuing through John Lorimer Worden V, the grandson of the former Arlington town moderator. "I suppose heroes come and go," Worden, 73, said. "But to take charge of something that had never been tried before, to battle this great behemoth, and to save the Union wooden fleet was an act of great courage."

Interest in the ship was rekindled with its discovery in 1973 and the years-long recovery of big pieces of the Monitor, including its turret, cannons, steam engine, propeller, and anchor. Today, they are displayed in a spacious wing of the Mariners' Museum or undergoing restoration in a mammoth, adjacent lab. "It's a mix between Jules Verne and Dr. Seuss," conservation manager David Krop said of the Monitor's radical design. "Even though it was 1862, the attention to detail and the quality of engineering was unbelievable."

To this day, the Monitor remains awe-inspiring to the technicians who protect it. "This was built 150 years ago, and some of these components look absolutely new," Krop said as he turned an original nut on a Monitor engine bolt. "It's an honor. Who gets to do this? This is the grandmother of all battleships."

To Anna Holloway, curator of the museum's Monitor collection, the ship is something else: "It's the coolest story I have ever, ever heard."

Howard Lowell stood on shore near the site of the legendary battle between… (John Tlumacki/Globe Staff)