REPORT OF THE COMMISSION TO LOCATE THE SITE OF THE FRONTIER FORTS OF PENNSYLVANIA.

VOLUME TWO.

CLARENCE M. BUSCH.

STATE PRINTER OF PENNSYLVANIA.

1896.

THE FRONTIER FORTS OF WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA.

Useful map with this chapter: Map of the Borough of Erie, 1837.

FORT LE BOEUF.—Erie County.

Pages 566-584.

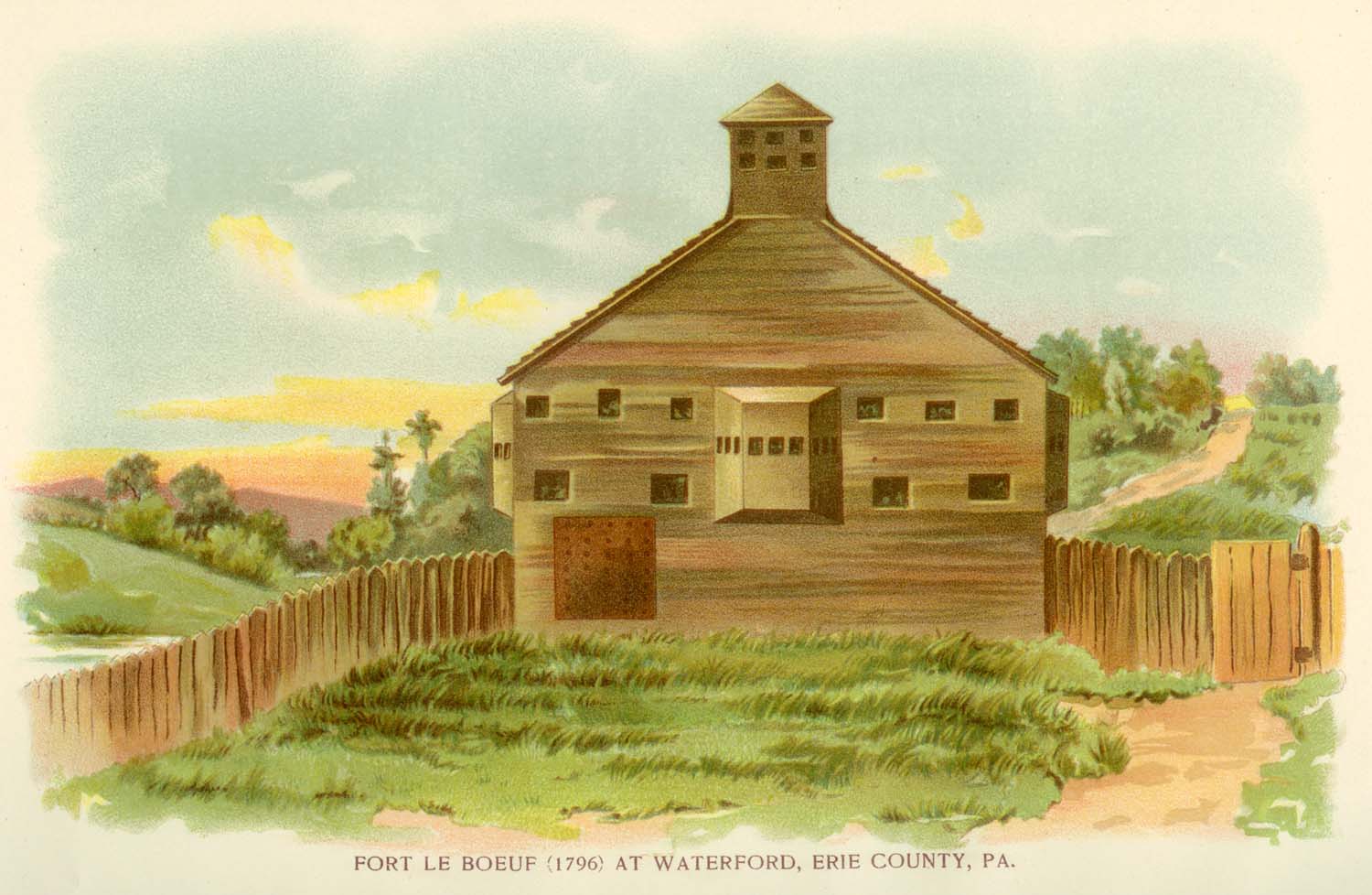

Illustration of Fort Le Boeuf, 1796.

Fort Le Boeuf was erected by the French in 1753, (1.) and an account of its building is given in the Deposition of Stephen Coffen, referred to and quoted from at length under the head of Presqu'Isle. The particulars of the erection of these posts are blended together in the one narration, so that in part it applies to both these forts. He states in his Deposition that "when Fort La Riviere Aux Boeufs (2) was finished (which is built of wood stockaded triangularwise, and has two log-houses on the inside) M. Morang (the Commander) ordered all the party to return to Canada for the winter season, except three hundred men, which he kept to garrison both forts and prepare materials against the spring for the building of other forts."

As the occupancy of these points by the French led to the sending out of George Washington by the Governor of Virginia, it is pertinent here to relate the particulars of his embassy:

"The news of the encroachments of the French having obtained, and the Ohio Company feeling aggrieved, applied for aid to Governor Dinwiddie, who claimed the country as a part of Virginia, and was also interested as a stockholder of the company. In George Washington, then but a youth, Governor Dinwiddie saw one fitted to lead in this difficult expedition. On the 30th of October, 1753, accompanied by Gist, the pioneer, Van Braam, a retired soldier, who had a knowledge of French, and John Davison, Indian interpreter, he set out for the wilderness.

"The instructions given Washington were to communicate at Logstown with the friendly Indians, and to request of them an escort to the headquarters of the French, to deliver his letter and credentials to the commander, and demand of him an answer in the name of the British sovereign, and an escort to protect him on his return. He was to acquaint himself with the strength of the French forces, the number of their forts, and their object in advancing to those parts, and also to make such other observations as his opportunities would allow.

"The Indians were not well satisfied as to the rights of either the French or English. An old Delaware sachem exclaimed, "The French claim all the lands on one side of the Ohio, and the English on the other; now where does the Indian's land lie? "Poor savages! between their father the French, and their brothers the English, they were in a fair way of being lovingly shared out of the whole country." Three of the sachems, Tannacharison, or Half-King, from his being subject to another tribe, Jeskakake, and White Thunder, accompanied Major Washington from Logstown, as they had been directed by Governor Dinwiddie, as well as for the purpose of returning to the French commander the war belts they had received from them. This implied that they wished to dissolve all friendly relations with their government. These Ohio tribes had been offended at the encroachments of the French, and had a short time previously sent deputations to the commander at Lake Erie, to remonstrate. Half-King, as chief of the Western tribes, had made his complaints in person, and been answered with contempt. "The Indians," said the commander, "are like flies and mosquitos, and the numbers of the French as the sands of the seashore. Here is your wampum, I fling it at you." As no reconciliation had been offered for this offense, aid was readily granted by them to the English in their mission.

"From Washington's Journal we get the following particulars: On their arrival at Venango (Franklin) they found the French colors hoisted at a house from which they had driven John Frasier (or Frazer], an English subject. There they inquired for the residence of the commander. Three officers were present, and one Capt. Jean Coeur [Joncaire] informed them that he had the command of the Ohio, but advised them to apply for an answer at the near fort, where there was a general officer. He then invited them to sup with them, and treated the company with the greatest complaisance. At the same time they dosed themselves plentifully with wine, and soon forgot the restraint which at first appeared in their conversation. In their half-intoxicated state they confessed that their design was to take possession of the Ohio, although the English could command for that service two men to their one. Still their motions were slow and dilatory. They maintained that the right of the French was undoubted from La Salle's discovery sixty years before, and that their object now was to prevent the settlement of the English upon the river or its waters, notwithstanding several families they had heard were moving out for that purpose.

"Fifteen hundred men had been engaged in the expedition west of Lake Ontario, but upon the death of the general, which had occurred but a short time before, all were recalled excepting six or seven hundred, who now garrisoned four forts, being one hundred and fifty men to a fort. The first of the forts was on French Creek (Waterford), near a small lake, about sixty miles from Venango, northwest; the next on Lake Erie (Presqu'Isle), where the greater part of their stores were kept, about fifteen miles from the other; from this, one hundred and twenty miles to the carrying place, at the Falls of Niagara (probably Schlosser) is a small fort, where they lodge their goods in bringing them from Montreal, from whence all their stores are brought; the next fort lay about twenty miles farther, on Lake Ontario (Fort Niagara).

"The second day at Franklin it rained excessively, and the party were prevented from prosecuting their journey. In the meantime, Capt. Jean Coeur sent for Half-King, and professed great joy at seeing him and his companions, and affected much concern that they had not made free to bring them in before. To this Washington replied that he had heard him say a great deal in dispraise of Indians generally. His real motive was to keep them from Jean Coeur, he being an interpreter and person of great influence among the Indians, and having used all possible means to draw them over to the French interests. When the Indians came in, the intriguer expressed the greatest pleasure at seeing them, was surprised that they could be so near without coming to see him, and after making them trifling presents, urged upon them intoxicating drinks until they were unfitted for business. The third day Washington's party were equally unsuccessful in their efforts to keep the Indians apart from Jean Coeur, or to prosecute their journey. On the fourth day they set out, but not without an escort planned to annoy them, in Monsieur La Force and three Indians. Finally, after four days of travel through mire and swamps, with the most unpropitious weather, they succeeded in reaching Le Boeuf.

"Washington immediately presented himself, and offered his commission and letters to the commanding officer, but was requested to retain both until Mons. Reparti should arrive, who was the commander at the next fort, and who was expected every hour. The commander at Le Boeuf, Legardeur de St. Pierre, was an elderly gentleman with the air of a soldier, and a knight of the military order of St. Louis. He had been in command but a week at Le Boeuf, having been sent over on the death of the late general.

"In a few hours Capt. Reparti arrived; from Presqu'Isle, the letter was again offered, and after a satisfactory translation a council of war was held, which gave Major Washington and his men an opportunity of taking the dimensions of the fort, and making other observations. According to their estimate, the fort had one hundred men, exclusive of a large number of officers, fifty birch canoes and seventy pine ones, and many in an unfinished state.

"The instructions he had received from Governor Dinwiddie allowed him to remain but seven days for an answer; and as the horses were daily becoming weaker, and the snow fast increasing, they were sent back to Venango, and still further to Shannopin's town, provided the river was open and in a navigable condition. In the meantime Commissary La Force was full of flatteries and fair promises to the sachems, still hoping to retain them as friends. From day to day the party were detained at Venango, sometimes by the power of liquor, the promise of presents, and various other pretexts, and the acceptance of the wampum had been thus far successfully evaded.

"To the question of Major Washington, ‘by what authority several English subjects had been made prisoners?' Captain Reparti replied, ‘that they had orders to make prisoners of any who attempted to trade upon those waters." The two who had been taken, and of whom they inquired particularly, John Trotter and James McClochlan; they were informed had been sent to Canada, but were now returned home. They confessed, too, that a boy had been carried past by the Indians, who had besides two or three white men's scalps.

"On the 15th, the commandant ordered a plentiful store of liquors and provisions to be put on board the canoes, and appeared extremely complaisant, while he was really studying to annoy them, and to keep the Indians until after their departure.

"Washington, in his Journal, remarks: ‘I cannot say that ever in my life I suffered so much anxiety as I did in this affair. I saw that every stratagem which the most fruitful brain could invent was practiced to win the Half-King to their interests, and that leaving him there was giving them the opportunity they aimed at. I went to the Half-King and pressed him in the strongest terms. He told me that the commandant would not discharge him until the morning. I then went to the commandant, and desired him to do their business, and complained of ill-treatment; for keeping them, as they were part of my company, was detaining me. This he promised not to do, but to forward my journey as much as possible. He protested that he did not keep them, but was ignorant of the cause of their stay; though I soon found it out; he promised them a present of guns, etc., if they would wait until morning." Their journey to Franklin was tedious and very fatiguing. At one place the ice had lodged so their canoes could not pass, and they were obliged to carry them a quarter of a mile. One of the chiefs, White Thunder, became disabled, and they were compelled to leave him with Half-King, who promised that no fine speeches or scheming of Jean Coeur should win him back to the French. In this he was sincere, as his conduct afterward proved. As their horses were now weak and feeble, and there was no probability of the journey being accomplished in reasonable time, Washington gave them, with the baggage, in charge of Mr. Van Braam, his faithful companion, tied himself up in his watchcoat, with a pack on his back containing his papers, some provisions and his gun, and, with Mr. Gist fitted out in the same manner, took the shortest route across the country for Shannopin's town.

"On the day following they fell in with a party of French Indians, who lay in wait for them at a place called Murdering town, now in Butler county. One of the party fired upon them, but, by constant travel, they escaped their company, and arrived within two miles of Shannopin's town, where trials in another form awaited them. They were obliged to construct a raft, in order to cross the river, and when this was accomplished, by the use of but one poor hatchet, and they were launched, by some accident Washington was precipitated into the river, and narrowly escaped being drowned. Besides this, the cold was so intense that Mr. Gist had his fingers and toes frozen. At Mr. Frasier's, (Turtle Creek) they met twenty warriors going southward to battle, and on the Ohio Company's trail, seventeen horses, loaded with materials and stores for a fort at the forks of the Ohio, and a few families going out to settle. On the 16th of February, Washington arrived at Williamsburg, and waited upon Governor Dinwiddie with the letter he had brought from the French commandant, and offered him a narrative of the most remarkable occurrences of his journey.

"The reply of Chevalier de St. Pierre was found to be courteous and well guarded. ‘He should transmit,' he said ‘the letter of Governor Dinwiddie to his general, the Marquis Du Quesne, to whom it better belongs than to me to set forth the evidence and reality of the rights of the king, my master, upon the lands situated along the Ohio, and to contest the pretensions of the king of Great Britain thereto. His answer shall be a law to me * * * * As to the summons to retire you send me, I do not think myself obliged to obey it. Whatever may be your instructions, I am here by virtue of the orders of my general, and I entreat you, sir, not to doubt one moment but that I am determined to conform myself to them with all the exactness and resolution which can be expected from the best officer. * * * * I made it my particular care to receive Mr. Washington with a distinction suitable to your dignity, as well as his own quality and merit. I flatter myself he will do me this justice before you, sir, and that he will signify to you, in the manner I do myself, the profound respect with which I am, sir, etc."

"Governor Dinwiddie and his council understood this evasive answer as a ruse to gain time, in order that they might in the spring descend the Ohio and take military possession of the whole country."

This expedition may be considered the foundation of Washington's fortunes. "From that moment he was the rising hope of the country. His tact with the Indians and crafty whites, his endurance of cold and fatigue, his prudence, firmness, and self-devotion, all were indications of the future man."

The fort is thus described by Washington: "It is situated on the south or west fork of French creek, near the water; and is almost surrounded by the creek, and a small branch of it, which form a kind of island. Four houses compose the sides. The bastions are made of piles driven into the ground, standing more than twelve feet above it, and sharp at the top, with port holes cut for the cannon, and loop-holes for the small arms to fire through. There are eight six-pound pieces mounted in each bastion, and one piece of four pounds before the gate. In the bastions are a guard-house, chapel, doctor's lodging, and the commander's private stores, round which are laid platforms for the cannon and the men to stand on. There are several barracks without the fort, for the soldiers dwellings, covered, some with bark, and some with boards, made chiefly of logs. There are also several other houses, such as stables, smith's shop, &c."

In 1756, a prisoner among the Indians, who had made his escape, gave the following particulars: "Buffaloes Fort, or Le Boeuf, is garrisoned with one hundred and fifty men and a few straggling Indians. Presqu' ile is built of square logs filled up with earth; the barracks are within the fort, and garrisoned with one hundred and fifty men, supported chiefly from a French settlement begun near it. The settlement consists, as the prisoner was informed, of about one hundred families." [This French settlement is not spoken of by any other person. M. Chauvignerie, as will be seen, states that there were no settlements or improvements near the forts Presqu' ile or Le Boeuf.] "The Indian families about the settlement are pretty numerous; they have a priest and schoolmaster, and some grist-mills and stills in the settlement." (3.)

In 1757, M. Chauvignerie, Jr., aged seventeen, a French prisoner, testified before a justice of the peace to this effect: "His father was a lieutenant of marines and commandant of Fort Machault, built lately at Venango." "At the fort they have fifty regulars and forty laborers, and soon expect a reinforcement from Montreal, and they drop almost daily some of the detachments, as they pass from Montreal to Fort Du Quesne. Fort Le Boeuf is commanded by my uncle, Monsieur de Verge, an ensign of foot. There is no captain or other officer there, above an ensign; and the reason of this is, that the commandants of those forts purchase a commission for it, and have the benefit of transporting the provisions and other necessaries. The provisions are chiefly sent from Niagara to Presqu' ile, and so from thence down the Ohio to Fort Du Quesne. Sometimes, however, they are brought in large quantities from southward of Fort Du Quesne. There are from eight hundred to nine-hundred, and sometimes one thousand men between Forts Presqu' ile to Le Boeuf. One hundred and fifty of these are regulars, and the rest Canadian laborers, who work at the forts and build boats. There are no settlements or improvements near the forts. The French plant corn about them for the Indians, whose wives and children come to the fort for it, and get furnished also with clothes at the King's expense. Traders reside in the forts, that purchase of them peltries. Several houses are outside the forts, but people do not care to occupy them, for fear of being scalped. One of their batteaux usually carries sixty bags of flour and three or four men. When unloaded, it will carry twelve men."

In Post's Journal for November, 1758, he says that the fort at Presqu'Isle was out of repair, and "the fort in Le Boeuf river is much in the same condition, with an officer and thirty men, and a few hunting Indians, who said they would leave them in a few days."

Thomas Bull; an Indian employed as a spy at the Lakes, arrived at Fort Pitt, in March, 1759, from a visit to the posts in that region. Le Boeuf he describes "as of the same plan with Presqu' ile, but very small; the logs mostly rotten. Platforms are erected in the bastion, and loopholes properly cut; one gun is mounted on a bastion and looks down the river. It has only one gate, and that faces the side opposite the creek. The magazine is on the right of the gate, going in, partly sunk in the ground, and above are some casks of powder, to serve the Indians. Here are two officers, a storekeeper, clerk, priest and one hundred and fifty soldiers, and as at Presqu' ile, the men are not employed. They have twenty-four batteaux, and a larger stock of provisions than at Presqu' ile. One Le Sambrow is the commandant. The Ohio is clear of ice at Venango, and French creek at Le Boeuf. The road from Venango to Le Boeuf is well trodden; and from thence to Presqu' ile is one half day's journey, being very low and swampy, and bridged most of the way."

Old Fort Le Boeuf being inland, was not ranked or fortified as a first-class station; yet, being situated on the "headwaters" of the Allegheny river, and at the nearest point of water communication between Lake Erie and the river, it was considered of much importance as a trading fort. It afforded protection to traders, hunters, and to many adventurers who passed between Canada and Fort Duquesne and the French possessions farther south. The portage between Presqu' Ile and Le Boeuf being only a little more than four leagues, the necessary goods, munitions of war, implements of agriculture, etc., were conveyed overland from the lake, and at Fort Le Boeuf embarked upon radeaux or rafts, to be transported to forts to the south and west along the river.

As the French were driven to the greatest straights at the siege of Fort Niagara, "the utmost confusion prevailed at forts Venango, Presqu'Isle, and Le Boeuf after the victory, particularly as Sir William Johnson sent letters by some of the Indians to the commander at Presqu'Isle, notifying him that the other posts must be given up in a few days.

"August 13 (1759), we find the French at Presqu'Isle had sent away all their stores, and were waiting for the French at Venango and Le Boeuf to join them, when they all would set out in batteaux for Detroit; that in an Indian path leading to Presqu'Isle from a Delaware town, a Frenchman and some Indians had been met, with the word that the French had left Venango six days before.

"About the same time, three Indians arrived at Fort Duquesne from Venango, who reported that the Indians over the lake were much displeased with the Six Nations, as they had been the means of a number of their people being killed at Niagara; that the French had burned their forts at Venango, Le Boeuf, and Presqu'Isle, and gone over the lakes." The author of the History of Erie county says that "the report was probably unfounded (of the burning of the forts), unless they were very soon rebuilt, of which we have no account." The posts, however, were shortly thereafter taken possession of by the English, and garrisoned by them. (4.)

Le Boeuf was one of the forts against which the savages, at the time of the uprising under Pontiac, directed their attention. The attack upon it has been told by Mr. Parkham, from original sources, and it is here in part reproduced:

"The available defences of Fort Le Boeuf consisted, at the time, of a single ill-constructed blockhouse, occupied by the ensign [Price],with two corporals and eleven privates. They had only about twenty rounds of ammunition each; and the powder, moreover, was in a damaged condition. At nine or ten o'clock, on the morning of the 18th of June, [1763], a soldier told that he saw Indians approaching from the direction of Presqu'Isle. Price ran to the door, and, looking out, saw one of his men, apparently much frightened, shaking hands with five Indians. He held open the door till the man had entered, the five Indians following close, after having, in obedience to a sign from Price, left their weapons behind. They declared that they were going to fight the Cherokees, and begged for powder and ball. This being refused, they asked leave to sleep on the ground before the blockhouse. Price assented, on which one of them went off, but very soon returned with thirty more, who crowded before the window of the blockhouse, and begged for a kettle to cook their food. Price tried to give them one through the window, but the aperture proved too narrow, and they grew clamorous that he should open the door again. This he refused. They then went to a neighboring storehouse, pulled out some of the foundation stones, and got into the cellar; whence, by knocking away one or two planks immediately above the sill of the building, they could fire on the garrison in perfect safety, being below the range of shot from the loopholes of the block-house, which was not ten yards distant. Here they remained some hours, making their preparations, while the garrison waited in suspense, cooped up in their wooden citadel. Towards evening, they opened fire, and shot such a number of burning arrows against the side of the blockhouse, that three times it was in flames. But the men worked desperately, and each time the fire was extinguished. A fourth time the alarm was given; and now the men on the roof came down in despair, crying out that they could not extinguish it, and calling on their officer for God's sake to let them leave the building, or they should all be burnt alive. Price behaved with great spirit. "We must fight as long as we can, and then die together," was his answer to the entreaties of his disheartened men. But he could not revive their drooping courage, and meanwhile the fire spread beyond all hope of mastering it. They implored him to let them go, and at length the brave young officer told them to save themselves if they could. It was time, for they were suffocating in their burning prison. There was a narrow window in the back of the blockhouse, through which, with the help of axes, they all got out; and, favored by the darkness—for night had closed in—escaped to the neighboring pine-swamp, while the Indians, to make assurance doubly sure, were still showering fire-arrows against the front of the blazing building. As the fugitives groped their way in pitchy darkness, through the tangled intricacies of the swamp, they saw the sky behind them lurid with flames, and heard the reports of the Indians guns, as these painted demons were leaping and yelling in front of the flaming blockhouse, firing into the loopholes, and exulting in the thought that their enemies were suffering the agonies of death within.

"Presqu'Isle was but fifteen miles distant, but, from the direction in which his assailants had come, Price rightly judged that it had been captured, and therefore resolved to make his way, if possible, to Venango, and reinforce Lieutenant Gordon, who commanded there. A soldier named John Dortinger, who had been sixteen months at Le Boeuf, thought that he could guide the party, but lost the way in the darkness; so that, after struggling all night through swamps and forests, they found themselves at daybreak only two miles from their point of departure. Just before dawn several, of the men became separated from the rest. Price and those with him waited for some time, whistling, coughing, and making such other signals as they dared, to attract their attention, but without success, and they were forced to proceed without them. Their only provisions were three biscuits to a man. They pushed on all day, and reached Venango at one o'clock on the following night. Nothing remained but piles of smoldering embers, among which lay the half-burned bodies of its hapless garrison. They continued their journey down the Allegheny. On the third night their last biscuit was consumed, and they were half dead with hunger and exhaustion before their eyes were gladdened at length by the friendly walls of Fort Pitt. Of those who had straggled from the party, all eventually appeared but two, who, spent with starvation, had been left behind, and no doubt perished."

Notwithstanding the treaty of Fort Stanwix and that of Fort Harmar, the cession of the Presqu'Isle lands was a sore subject to many of the Chiefs of the Six Nations, and especially to their master-spirit, Brant, the Mohawk chieftain. It was claimed that the treaty was invalid, Cornplanter having sold their lands without authority. Brant's favorite design was to restrict the Americans to the country east of the Allegheny and Ohio; and he not only strenuously opposed and denounced every treaty that interfered with his plan, but was active in his endeavors to unite all the northern and western nations in one great confederacy, and, if necessary to protect his favorite boundary by a general war. (5.)

From this cause with the abetting of England and the disposition of the Senecas and other Indian tribes within the borders of Pennsylvania, it was necessary to create a military establishment, by the general government with the co-operation of the State, to facilitate settlements and protect the settlers in this region. From the papers relating to this establishment we extract the following (6):

On the 29th of June, 1794, Andrew Ellicott writes to Governor Mifflin from Fort Le Boeuf, as follows:

"After repairing Fort Franklin (Venango), we proceeded to this place, and are now beginning to strengthen the works here, so as to render it a safe deposit for military and other stores; and in doing which, agreeable to instructions economy shall be strictly attended to."

Prior to this time the place had been occupied by the State as appears from the report of Colonel John Wilkins to Secretary Dallas. Writing from Pittsburgh, May 23, 1794, he says: "The troops of the State took possession of the Forks of French creek, about two miles below the old post of Le Boeuf, and had a small blockhouse built to which place I accompanied them."

He states that they would remain there until they had procured materials for erecting blockhouses at Le Boeuf.

On June 26th, 1794, a council was held by Mr. Ellicott and Capt. Denny with representatives of the Six Nations at Le Boeuf (Waterford). The Six Nations demanded a removal of the whites from the Lake region and objected to the settlement of Presqu'Isle. On the 27th June, Mr. Andrew Ellicott made a report of the conference with the Indians, and advised the erection of three blockhouses "on the Venango Path."— One of which should be at Mead's settlement (Meadville), and the other two at Le Boeuf and Venango.

From Le Boeuf, Andrew Ellicott reports to Governor Mifflin, June 29th, 1794 :"After repairing Fort Franklin, we proceeded to this place, and are now beginning to strengthen the works here, so as to render it a safe deposit for military and other stores."

On July the 4th, 1794, he reports:"The detachment of State troops commanded by Capt. Denny yesterday moved into the new fort at this place, which is now defensible not only against the Six Nations, but all the Indians at variance with the U. S. In the execution of the plan, Capt. Denny merits the highest commendation for his steady exertions and activity, and I can with truth assure you, in all my experience I never saw a work of equal magnitude progress with equal rapidity. The new fort has yet no name."

Major E. Denny reported to Governor Mifflin, from Le Boeuf, August 1st, 1794: "As it has been the prevailing opinion, that this post will not be continued, unless a sufficient force comes forward, and we advance to Presqu'Isle, I have done no more than what appeared necessary for a temporary accommodation, and for our own security. Mr. Ellicott has favored us with a draft of the place. It is sent to you by this conveyance, and will give an idea how we are situated. The riflemen occupy the whole of the two front blockhouses, and the lower part of the other two. The detachment of the artillery, and all the officers, remain in their tents, on the ground marked officers quarters, soldiers barracks, magazine and guard house. The two houses in front were built by the party that came on first, and are not calculated for taking in cannon. On each of the others second floor, we have a six-pounder, and over each gate is a swivel. The situation is unequaled by any in this country, Presqu'Isle excepted. One disadvantage only, that is a hollow way parallel with our rear, and within gun shot, that will cover any number of Indians; but, with a few more men, and extending the work, that may be perfectly secured. We have it examined every morning, before the gates are thrown open. The Indians, early in the spring, came frequently to this post; but since the declaration of the Six Nations, we have not had one to come in. ‘Tis a few days since we saw two or three viewing the plan. We hoisted a white flag, but they disappeared."

In a report to Gov. Mifflin by John Adlum, August 31st, 1794, it is said: "Capt. Denny has endeavored to keep up military discipline at La Boeuf, and has got the ill will of his men generally; they say he is too severe, but from inquiry I cannot find he has punished any of them, although some of them deserve death, having been found asleep at their posts."

Cornplanter with his chiefs was there at the time, being fed and supported by the State and federal authorities. He gave the agent, Mr. Adlum, notice that it was unnecessary to send any more provisions to La Boeuf, as they would soon have to leave it."

Mr. Adlum adds that after writing his report "all is quiet at Le Boeuf. The mutiny—at which he had hinted—arose from some of the soldiers, who stole the Commandant's brandy, and got drunk." One of the soldiers had snapped a gun at Captain [Major] Denny, and it was with difficulty they could take him to Fort Franklin. "Others were punished, and now all is in order."Shortly after this, all the surveyors, and persons employed in pursuance of the act, were drawn off, and only a small garrison left at La Boeuf. On January 16, 1795, Major Denny reports to the Governor that the detachment left at La Boeuf were relieved the last of December. In a letter to the Secretary of War, March 11th, 1795, he says: "La Boeuf is built upon a handsome eminence, at the head of the navigation, immediately upon the ground formerly occupied by the French and English. It will accommodate a company of men well; but as it was only intended as an intermediate post to Presqu'Isle, a small command of twenty-five men will answer every purpose, and there will be plenty of store room for depository whatever may be sent forward."

From the History of Erie county, by Miss Laura G. Sanford, we have the following information relating to this period. Speaking of the act of April 18th, 1795, "to lay out a town at Presqu'Isle, etc.," she says:

It was provided in section thirteenth, "that it shall be lawful for the Governor, with the consent of the individuals, respectively, to protract the enlistments of such part of the detachment of State troops, or such part as may be in garrison at Fort La Boeuf, or to enlist as many men as he shall deem necessary, not exceeding one hundred and thirty, to protect and assist the commissioners, surveyors, and other attendants intrusted with the execution of the several objects of this act: Provided, always, nevertheless, That as soon as a fort shall be established at Presqu'Isle, and the United States shall have furnished adequate garrisons for the same, and for Fort Le Boeuf, the Governor shall discharge the said detachments of State troops, except the party thereof employed in protecting and assisting the commissioners, surveyors, and other attendants as aforesaid, which shall be continued until the objects of this act are accomplished, and no longer."

"And section fifteenth, "that in order to defray the expenses of making the survey, at Fort La Boeuf, and the various surveys and sales herein directed, and to maintain the garrison at Fort La Boeuf, there shall be, and hereby is, appropriated the sum of $17,000, to be paid by the Treasurer on the warrants of the Governor."

"When Judge Vincent settled in Waterford in 1797, he says: "There were no remains of the old French fort excepting the traces on the ground, and these traces were very distinct and visible." Fifteen years after, a cellar and a deep well were the only visible remains. Cannon, bullets, etc., have been found occasionally below the surface, and fragments of human skeletons pervade the soil. From the first settlement to the present time men have, at intervals, been searching for treasures on the sites of Le Boeuf and Presqu'Isle, with all the helps afforded by the magnet and mineral rod. At La Boeuf, in 1860, a man, digging under the direction of the "spirits," discovered below the surface a stone wall laid up with mortar, which would probably have a radius of one hundred feet. Within this was the foundation of a blacksmith's forge, or indications of one—as burnt stone, cinders, pieces of iron of all shapes, and of no conceivable use, guns, gun-locks, bayonets, and parts of many implements of war.

Judge Vincent says further: "On the same ground, in 1797, stood a stockade fort built by Maj. Denny in 1794; it was commanded by an officer of the army, Lieut. Marten, with twelve or fifteen soldiers. The same year (1797) a new fort was built, which is still occupied by a family, though very much dilapidated, and some parts apparently ready to fall. This blockhouse was at one time a storehouse; in 1813 (after the battle of Lake Erie) a body of prisoners and wounded men were there quartered; it was next connected with other buildings, the whole being weatherboarded, and a respectable hotel constituted. The main street of the borough running from north to south passes in front of the "Blockhouse Hotel," and over the same ground which was occupied by the French and first American forts."

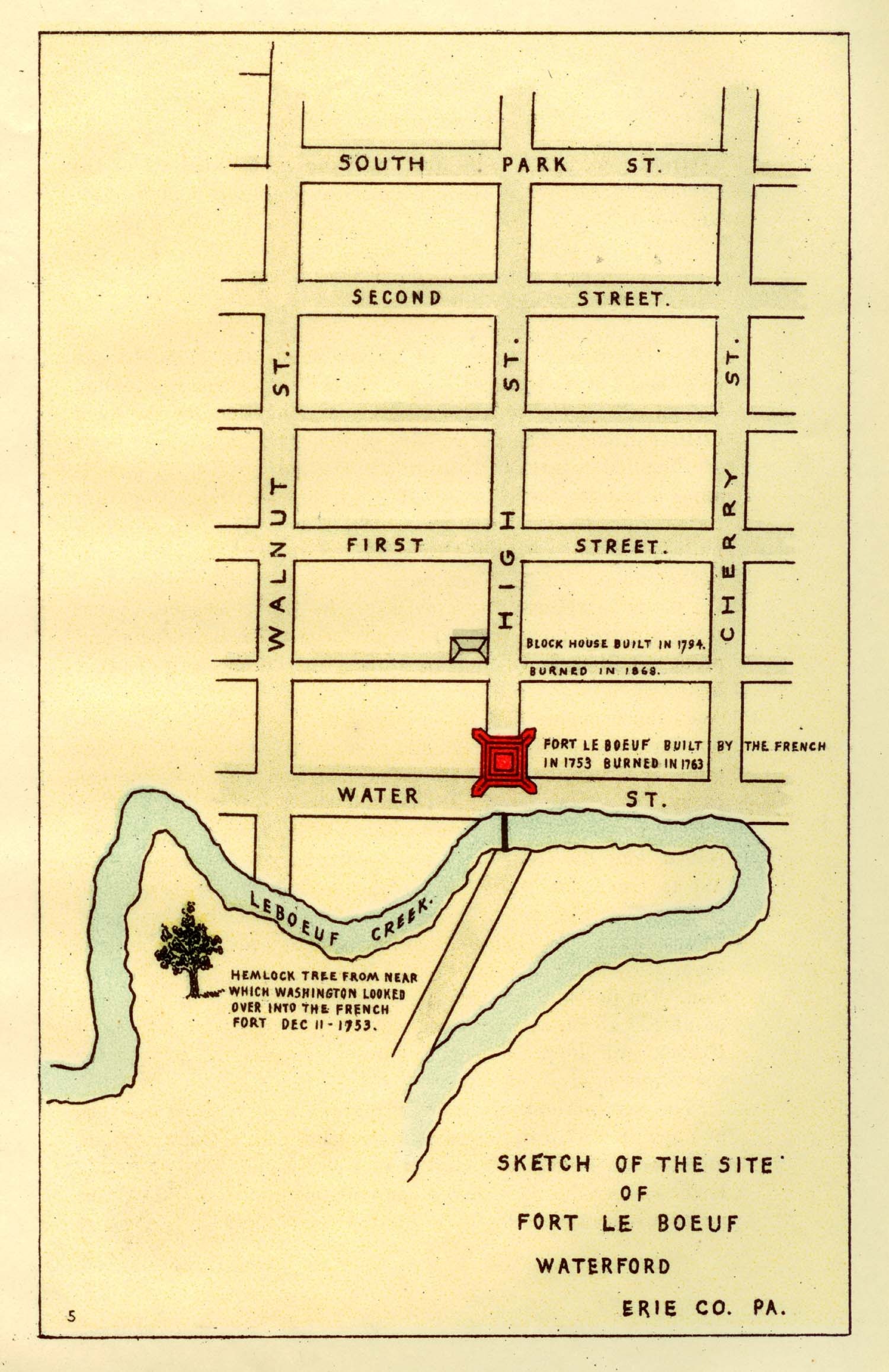

Sketch of the Site of Fort Le Boeuf, Waterford, Erie Co., PA.

"In the neighborhood of the depot, two miles northeast of tire blockhouse, spikes, bullets, cannon balls, etc., have been found. In another part of the town, a quarter of a mile from the fort, a hillock is called "Washington's Mound" from the fact (as tradition has it) that Washington, when on his mission in 1753, spent a night there."

The extract following is taken from a manuscript paper furnished the writer by Mrs. Mary Judson Snowden, of Waterford, Pa., a lady specially conversant with the history of Le Boeuf, and one who has had the benefit of the personal recollections of those who were a part of what they related.

"State troops reached Waterford in May, of that year [1794], and built the second fort or blockhouse, which in turn was covered with clapboards, furnished with the conveniences of the time, a large addition made in the rear, and a large porch extending over the sidewalk in front and supported by colonial pillars. It was used as a hotel and residence up to 1868, when it caught fire in some unknown way and burned to the ground —the old logs, and ancient port-holes showing as the modern surface covering burned away. * * * The exact site of the original French Fort is not positively known, but was near the centre of High street, a little below First alley, and, of course, now belongs to the street, which, however, is one hundred feet wide. The site of the second fort or blockhouse, which stood till 1868, is just above First alley, fronting on High street. The spot is fenced in, and used as a yard. The old cellar with all the debris of crumbling walls, old chimneys, &c., is just as the fire left it over a quarter of a century ago. It belongs now to the heirs of John W. Mauross."

______

Notes to Fort Le Boeuf.

(1.) I desire to acknowledge the advantages I have had from extracting from the History of Erie county, by Miss Laura G. Sanford, much material used in this article. As in the article on Presqu'Isle, I have likewise in this on Le Boeuf been assisted by her manuscript contributions, very materially.

The papers belonging to the post-revolutionary period, which have been quoted from, will be found for the most part in the Sixth Volume of Penn'a Archives, second series—among the "Papers Relating to the Establishment of Presqu'Isle."(2.) "The ancient name of the river now called Allegheny, was Ohio, or, as the French called it, "La Belle Riviere," Beautiful river.—French creek, in Coffen's statement, is called Aux Boeufs." On the leaden plate buried by Celoron, it is called Toradakin. The French invariably called it the River Aux Boeufs [River of Beeves or Buffaloes—Beef River]. In one of the French despatches it is said that it was called by the English, "Venango" river. At the time of Washington's visit here, he rechristened it French creek, by which name it has been known ever since.

The road from Venango to Le Boeuf was described in 1759 as being "trod and good;" thence to Presqu'Isle, about half a day's journey, as "very low and swampy and bridged almost all the way."

The portage or causeway is frequently alluded to. It required great labor to keep it open, and it was often in a miserable condition. In 1782 the causeway from Presqu'Isle to Le Boeuf is said to have been "rotten and impassable."

"In 1813 all the naval stores needed for the construction of Perry's fleet were brought from Pittsburgh to Franklin, and then up the creek to Waterford, and then by land to Erie. It is probable that French creek was navigable all the year in Washington's time"—that is about the time he was there— 1753. [Hist. Venango County, supra., p. 21.]

For condition of these roads see report of Major Denny to Timothy Pickering, Secretary of War, Archives vi, 815, sec. ser.

"One of the first appropriations for the northwestern part of the State, in 1791, was four hundred pounds for the improvement of French creek (besides four hundred pounds for the road from Le Boeuf to Presqu'Isle), and in 1807 we find five hundred dollars were to be set apart from the sale of town and out-lots of the Commonwealth, adjoining Erie, for clearing and improving the navigation of Le Boeuf and French creeks from Waterford to the south line of the county.

"Here it may not be out of place to give a short description of French creek. It was formerly called Venango creek, or rather In-nan-ga-eh, and it is a beautiful, transparent, and rapid stream For many miles from its confluence with the Allegheny it is less than one hundred feet in width. At some seasons its waters are navigable to Waterford for boats carrying twenty tons, yet for a few weeks of summer it cannot usually be navigated by any craft larger than a canoe."Washington, in his Journal, calls Le Boeuf creek the Western Fork, which is correct, but besides this there are three others, and these are now particularly designated."

(3) These statements are in Third Volume of Archives. And herein see further about the settlements there, which were only "military settlements."

(4) After the defeat of the French before Fort Niagara, nearly all the French officers being killed or captured, their followers, "after heavy loss, fled to their canoes and boats above the cataract, hastened back to Lake Erie, burned Presqu'Isle, Le Boeuf, and Venango, and, joined by the garrisons of those forts, retreated to Detroit, leaving the whole region of the upper Ohio in undisputed possession of the English." [Parkman, Montcalm & Wolfe, Vol. ii, p 247.]

"At the beginning of 1761, of the whole number of troops raised by the Province for the late war, there yet remained near one hundred and fifty men undischarged, of which, about one half were employed in transporting provisions from Niagara, and in garrisoning the forts at Presqu'Isle and Le Boeuf, till they could be relieved by detachments from the Royal Americans, which from the thinness of that regiment and from the large extent of the territory over which their duty extended having not been done so soon as had been expected, these still remaining could not march down at the same time with the rest of the Provincials." (Gov. Hamilton to the Assembly, Jan. 8th, 1761. Col. Rec. viii, 513.)

(5.) Day's Historical Collections, p. 316.

(6.) See Pa. Arch., Vol. vi, second series.

______