REPORT OF THE COMMISSION TO LOCATE THE SITE OF THE FRONTIER FORTS OF PENNSYLVANIA.

VOLUME TWO.

CLARENCE M. BUSCH.

STATE PRINTER OF PENNSYLVANIA.

1896.

THE FRONTIER FORTS OF WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA.

Pages 358-381.

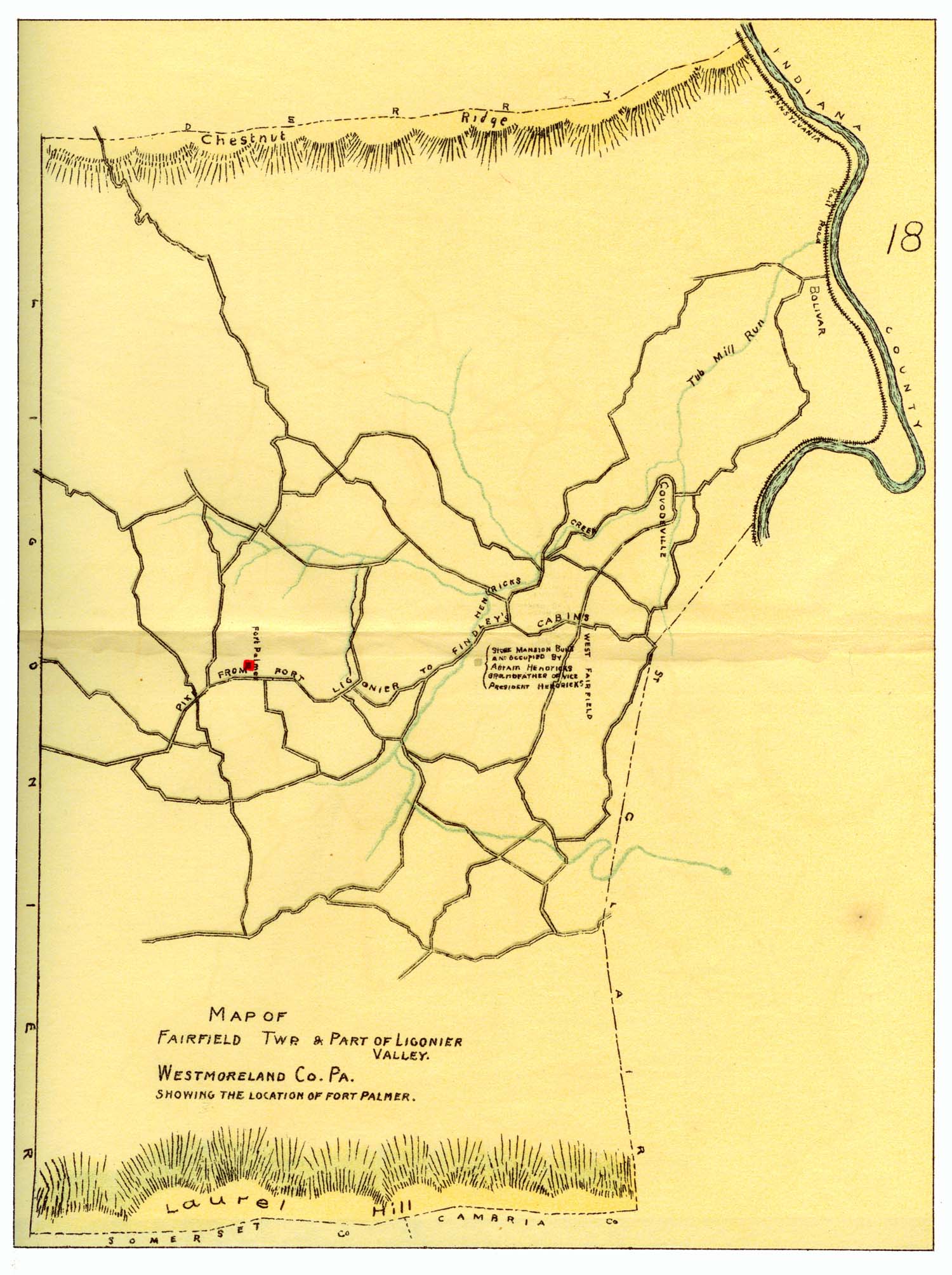

Map of Fairfield Twp & Part of Ligonier Valley, Westmoreland, Co.

PALMER'S FORT.

The approximate date of the erection of Fort Palmer, or Palmer's Fort, may be learned from the record of conveyances. Robert Nox (Knox) conveyed to John Palmer the tract of land on which the stockade was built, by deed March 11th, 1771. John Palmer, farmer, of Fairfield township, on the 24th of Jan., 1776, passed over the paper title to Charles Griffen, by a deed acknowledged before Robert Hanna, Judge, etc. Charles Griffen obtained a patent for this land from the Commonwealth, Feb. 10th, 1787, in which it is described as a "tract of land situate in Fairfield township, Westmoreland county, Pa., called ‘Fort Palmer.'"

This stockade was in existence early in the Revolution, and it might have been a place of resort in the troubles of 1774. This is altogether probable, but not at present provable. In the Journal kept at Ligonier during the building of the Revolutionary stockade there, Fort Palmer was then, (Nov. 1777), a place of defence in which settlers had gathered. It is mentioned frequently in sketches of the history of the families of the early settlers, or in obituary notices of the earlier pioneers, as a place of refuge, and is associated in the traditions of the Conemaugh and Ligonier Valleys with nearly all the Indian warfare and the perils of that frontier. It, however, is not to be forgotten that events which rest for the most part on oral tradition, are very apt to be shifted about to correspond with periods of time which are of marked prominence or illusively distant. All the testimony which is unimpeachable, in connection with this stockade, belongs to the Revolutionary era. There is probably no settler's fort in Westmoreland county with so much connected with it, and so little available, as this stockade. It was constructed early and remained among the last of the forts erected by the settlers as a defense against the Indians. From its location it was the point towards which the settlers to the north of the Conemaugh, in what is now Indiana and Cambria counties, fled. Here they remained while, danger was imminent, and from here they went forth with their families and effects when it was safe to venture back to their clearings.

In that most explicit letter in which Col. Archibald Lochry the County Lieutenant reported the depredations of the savages in the outbreak of the autumn of 1777, (Arch., v, 741.) he says: "The destressed situation of our country is such, that we have no prospect but desolation and destruction; the whole country on the north side of the road (Forbes Road) from the Allegheny mountains to the river is all kept close in forts; and can get no subsistence from their plantations." After specifying the particulars of this raid, he states that "eleven other persons [have been] killed and scalped at Palmer's Fort, near Ligonier, amongst which is Ensign Woods."

The Council of Safety to the Delegates of Pennsylvania in Congress, on the 14th of November, 1777, giving an account of the distressed condition of this frontier, says: "This Council is applied to by the people of the County of Westmoreland in this Commonwealth with the most alarming complaints of Indian depredations. The letter of which the enclosed is a copy, will give you some idea of their present situation. We are further informed by verbal accounts, that an extent of sixty miles has been evacuated to the savages, full of stock, corn, hogs and poultry; that they have attacked Palmer's Fort about seven miles distant from Fort Ligonier without success; and from the information of White Eyes, and other circumstances, it is feared that Fort Ligonier has, by this time been attacked."

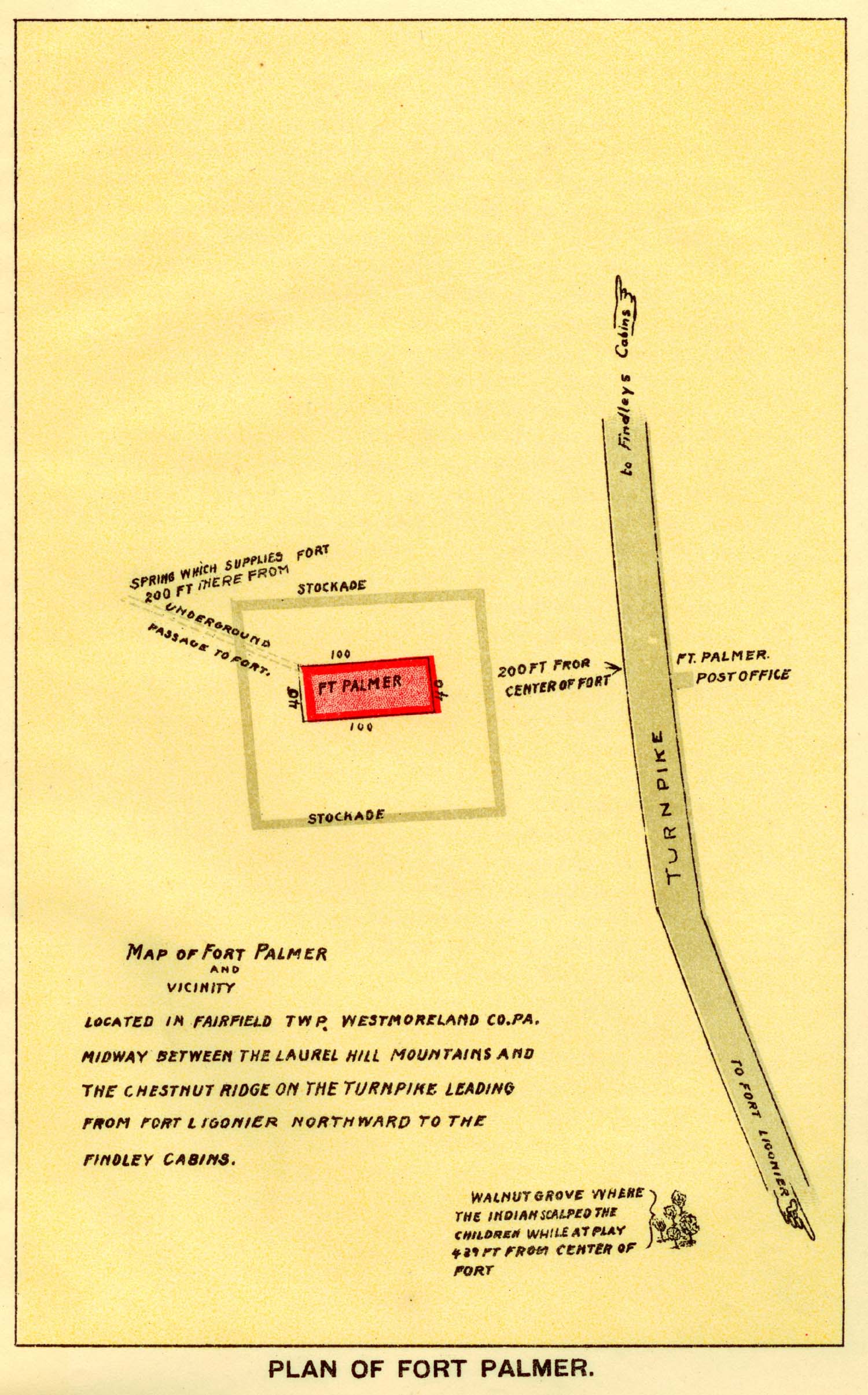

In the Journal to Fort Preservation, (Ligonier), will be found narrated some events properly belonging to the history of Fort Palmer. The condition of affairs as they existed about this fort during the frontier wars may be imagined from the detail as given in that Journal covering as it does but a very short space of time. The killing of the two children within two hundred yards of the fort, mentioned in the Journal for Oct. 22nd, is a fact singularly preserved in an unbroken tradition from the time it occurred. William Reynolds, Esq., of Bolivar, Pa., a descendant of the George Findley mentioned above, writes under date of Nov. 15th, 1894, and repeats the details, giving the approximate distance from the fort, and other circumstances; and this gentleman had never heard of the existence of the Journal, but had received his version of the occurrence when very young and had carried it in his memory as first narrated. It is seldom that such an incident has been so clearly preserved. On the accompanying map and plan, which was furnished at the instance of Jeff W. Taylor. Esq., of Greensburg, Pa., the grove in which these children were killed is marked, as the place is pointed out at this day. It is a matter of regret that not more authenticated data is obtainable, and that in a community in which there were so many intelligent persons interested in perpetuating its history, none should have been found to do so.

______

SHIELD'S FORT.

Among the petitions that were presented to Governor Penn on the occasion of the alarm from the uprising in 1774, was one from a large number of people "who had assembled at the house of a certain John Shields, near to, or about five or six miles of Hannas Town and on the Loyalhanna, where, as a defense for their wives and families, they had erected a small fort, and by the direction of the gentlemen of the association took up arms for the general defense. Your petitioners, (say they), thought themselves extremely happy and secure, when your honor and the Assembly were pleased to order a number of troops to be raised for our general assistance and protection; but we are now rendered very uneasy by the removal of these troops, their arms and ammunition, on which our greatest dependence lay, and which we understand are ordered to Kittanning, a place at least twenty-five or thirty miles distant from any of the settlements. Your petitioners being left thus exposed without arms, ammunition or the protection of these removed troops, humbly conceive themselves to be in danger of the enemy, and are sorry to observe to your honor, that it is ours, as well as the general opinion, that removing the troops to so distant and uninhabitated part of the province as Kittanning is, cannot answer the good purposes intended, but seems to serve the purposes of some who regard not the public welfare." (Rupps', Western Pa., Appx., 260.) The petition was signed by over a hundred persons, and the list includes the names of many whose descendants live within that neighborhood.

This structure, as stated, was erected on the farm of John Shields, one of the early settlers on the Loyalhanna, near, (now) New Alexandria, Westmoreland county. John Shields was one of the five commissioners appointed in 1785 to purchase a piece of land for the inhabitants of the county on which to erect a court-house and jail, whose labors resulted in the selection of Greensburg.

This blockhouse was within communicating distance of Wallace's Fort, Barr's Fort and Hannastown, and on occasions of alarm the inhabitants fled to the one most available. It continued as a place of resort and shelter during the Revolution. Persons living have seen some of the remains of the so-called fort. "It was built on an eminence above the present Shields' residence now occupied by the family of the late Matthew Shields. It was but a few rods distant from the line which separated the Shields farm from one which Alexander Craig purchased from him, and which was known as the "Craig" farm. It was thus sometimes called Craig's Blockhouse, or Craig's Fort, but it was not known by that name to those of this locality. There is no doubt the Craigs assisted in building it. It was perhaps a mile from New Alexandria and eight miles from Greensburg. [MS. Mrs. Margaret Craig, New Alexandria. Pa.]

______

WALTHOUR'S FORT.

Walthour's Fort, as Mr. Brackenridge, in the article which we quote at length hereto, says "was one of those stockades or blockhouses to which a few families of the neighborhood collected in times of danger, and going to their fields in the day returned at night to this place of security." It was located, with regard to the present surroundings, eight miles west of Greensburg on the turnpike to Pittsburgh, twenty-three miles east of Pittsburgh, four miles south of Harrison City (Byerly Station, Forbes Road), and one and one-half miles from Irwin. It was built on the farm of Christopher Walthour, (as the name is usually spelled now by the family, but spelled then Waldhower), who owned a large body of land there. The farm remained in the Walthour family and name until 1868—near one hundred years. Christopher, his brother George, the Studebakers, Kunkles, Byerleys, Williards, Irwins, Hibergers, Wentlings, Baughmans, Gongawares, Fritchmans, Buzzards, Kifers, etc., belonged to that settlement.

The land is now owned by Michael Clohessey. The site of the blockhouse and stockade, is about three hundred yards south of the turnpike, a little to the left of the barn, between two springs of water. The stockade enclosed the house of Walthour, and "inside of this enclosure and blockhouse all the people of the community would gather. The dead"—(when Williard was killed, as hereafter referred to, and others not individualized),—"were buried near the old fort. Afterwards an apple tree grew upon the spot spontaneously, and my father (says Joseph S. Walthour. Esq., MS.) always took the best care of it, because it marked the grave of the dead there buried."

It would appear that the region about this fort suffered most during the seasons of 1781-2, and especially just before the destruction of Hannastown. Many petitions sent to Gen. Irvine from citizens of Washington and Westmoreland counties, show, in a clear light, the dangers and exposures of the border throughout this period. Of these petitions there was one from Brush creek, dated June 22d 1782, of which Mr. Butterfield, the erudite historian of the Western Department, says: "This petition, so unexceptionably elegant in diction, as well as powerfully strong and clear in the points stated, is signed by nineteen borderers, mostly Germans. The document itself is in a bold and beautiful hand. It would be hard to find in all the Revolutionary records of the west a more forcible statement of border troubles, in a few words, than this." (Wash.-Irv. Cor., 301, note.)

The names of these petitioners are given by Rev. Cyrus Cort in his Col. Henry Bouquet, etc., p. 98. They are as follows: George, Christopher, Joseph and Michael Waldhauer (Walthour), Abraham and Joseph Studabedker, Michael and Jacob Byerly, John and Jacob Rutdorf, Frederick Williard, Wiesskopf (Whitehead), Abraham Schneider, Peter and Jacob Loutzenheiser, Hanover Davis, Conrad Zulten, Garret Pendergrast and John Kammerer. The following extracts are from the petition: They represent: "That since the commencement of the present war, time unabated fury of the savages hath been so particularly directed against us, that we are, at last, reduced to such a degree of despondency and distress that we are now readly to sink under the insupportable pressure of this very great calamity. * * * * That the season of our harvest is now fast approaching, in which we must endeavor to gather in our scanty crops, or otherwise subject ourselves to another calamity equally terrible to that of the scalping-knife—and from fatal experience, our fears suggest to us every misery that has usually accompanied that season. * * * * Wherefore we humbly pray for such an augmentation of our guard through the course of the harvest-season as will enable them to render us some essential service. * * * * And as we have hitherto been accustomed to the protection of the continental troops during the harvest-season we further pray, that we may be favored with a guard of your soldiers, if it is not inconsistent with other duties enjoined on you."

A small force of continentals was stationed at Turtle creek, a post on the old Penn'a road where Turtle creek crossed. These were intended to protect all that settlement round about.

Of Walthour's Fort, little would be known outside of well-preserved traditions but for an event which, on account of its unique character and the circumstances connected with it, had attracted the notice of H. H. Brackenridge who has in his narration redeemed this fort from a fate which otherwise would have been obscure. Mr. Brackenridge, who later was a Justice of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, was at that time a practicing attorney at Pittsburgh. In his leisure he directed his vigorous intellect to literary pursuits, and wrote various articles on such subjects as partook of an historical or legal complexion. Thus, whatever he wrote for the public has great value, and from his method of treatment his articles are of peculiar interest to the antiquary. His story of the lame Indian depicts a peculiar phase of frontier life; and as its verity has never been questioned, we are constrained to admit is as a record which deserves to be perpetuated. The account, therefore, is here given, accompanied with the letters illustrating it. It is as follows:

"In Pittsburgh (Penna.), about the year 1782, one evening just in the twilight, there was found sitting in a porch, an Indian with a light pole in his hand. He spoke in broken English to the person of the house who first came out, and asked for milk. The person (a girl) ran in and returning with others of the family they came to see what it was that had something like the appearance of a human skeleton. He was to the last degree emaciated, with scarcely the semblance of flesh upon his bones. One of his limbs had been wounded; and it had been on one foot and by the help of the pole that he had made his way to this place. Being questioned, he appeared too weak to give an account of himself, but asked for milk, which was given him, and word sent to the commanding officer of the garrison at that place, (General William Irvine), who sent a guard and had him taken to the garrison. After having had food and now being able to give some account of himself, he was questioned by the interpreter (Joseph Nicholson). He related that he had been on Beaver river trapping, and had a difference with a Mingo Indian who had shot him in the leg, because he had said he wished to come to the white people.

"Being told that this was not credible, but that he must tell the truth, and that in so doing he would fare the better, he gave the following account, to wit: that he was one of a party who had struck the settlement in the last moon, and attacked a fort and killed some and took some prisoners.

"This appeared to be a fort known by the name of Walthour's fort by the account which he gave, which is at the distance of twenty-three miles from the town on the Penn'a road towards Philadelphia, and within eight miles of what is now Greensburg. He stated that it was there that he received his wound.

"The fact was that the old man Walthour, his daughter and two sons were at work in the field, having their guns at some distance, and which they seized on the appearance of the Indians, and made towards the fort. This was one of these stockades or blockhouses to which a few, families of the neighborhood collected in times of danger, and going to their fields in the day returned at night to this place of security.

"These persons in the field were pursued by the Indians and the young woman taken. The old man with his son kept up a fire as they retreated and had got to the distance of about an hundred yards from the fort when the old man fell. An Indian had got upon him and was about to take his scalp, when one in the fort directing his rifle, fired upon the Indian who made a horrid yell and made off, limping on one foot. This was in fact the very Indian, as it now appeared, that had come to the town. He confessed the fact, and said, that on the party with which he was, being pursued, he had hid himself in the bushes a few yards from the path, along which the people from the fort in pursuit of them came. After the mischief was done, a party of our people had pursued the Indians to the Allegheny river, tracing their course, and had found the body of the young woman whom they had taken prisoner but had tomahawked and left. The Indian, as we have said, continuing his story to the interpreter, gave us to understand that he lay three days without moving from the place where he first threw himself into the bushes, until a pursuit might be over, lest he should be tracked; that after this he had got along on his hands and feet, until he found this pole in the marsh which he had used to assist him, and in the meantime had lived on berries and roots; that he had come to a post some distance, from here, where a detachment of soldiers was stationed, and thought of giving himself up, and lay all day on a hill above the place thinking whether he would or not, but seeing that they were all militia men and no regulars, he did not venture.

"The Indians knew well the distinction between regulars and militia, and from these last they expected no quarter.

"The post of which he spoke was about twelve miles from Pittsburgh on the Penn'a road at the crossings of what is called Turtle creek. It was now thirty-eight days since the affair of Walthour's fort, and during that time this miserable creature had subsisted on plants and roots and had made his way on one foot by the help of a pole. According to his account, he had first attempted a course to his own country by crossing the Allegheny river a considerable distance above the town, but strength failing to accomplish this he had wished to gain the garrison where the regular troops were; having been at this place before the war; and, in fact, he was now known to some of the garrison by the name of Davy. I saw the Indian in the garrison after his confession, some days, and was struck with the endeavors of the creature to conciliate good-will by smiling and affecting placability and a friendly disposition.

"The question was now what to do with him. From the mode of war carried on by the savages, they are not entitled to the laws of nations. But are we not bound by the laws of nature, to spare those that are in our power; and does not our right to put to death cease, when an enemy ceases to have it in his power to injure us. This diable boiteux, or devil on two sticks, as they may be called—his leg and his pole—would not seem to be likely to come to war again.

"In the meantime the widow [Mrs. Mary Williard] of the man who had been killed at Walthour's fort and mother of the young woman who had been taken prisoner and found tomahawked, accompanied by a deputation of the people of the settlement, came to the garrison, and addressing themselves to the commanding officer, demanded that the Indian should be delivered up that it might be done with him, as the widow and mother and relations of the deceased should think proper. After much deliberation, and the country being greatly dissatisfied that he was spared, and a great clamour prevailing through the settlement, it was thought advisable to let them take him, and he was accordingly delivered up to the militia of the party which came to demand him. He was put on a horse and carried off with a view to take him to the spot where the first mischief had been done (Walthour's fort). But, as they were carrying him along, his leg, the fracture of which by this time was almost healed, the surgeon of the garrison having attended to it, was broken again by a fall from the horse which had happened some way in the carrying him. The intention of the people was to summon a jury of the country and try him, at least for the sake of form, but, as they alleged, in order to ascertain whether he was the identical Indian that had been of the party of Walthour's fort; though it was not very probable that he would have had an impartial trial, there having been a considerable prepossession against him.

"The circumstance of being an Indian would have been sufficient evidence to condemn him. The idea was, in case of a verdict against him, which seemed morally certain, to execute him, according to the Indian manner, by torture and burning. For, the fate of [Colonel William] Crawford and others, was at this time in the minds of the people, and they thought retaliation a principle of natural justice. But while the jury were collecting, some time must elapse, that night at least; for he was brought to the fort, or blockhouse in the evening. Accordingly a strong guard was appointed to take care of him, while, in the meantime, one who had been deputed sheriff, went to summon a jury, and others to collect wood and materials for the burning, and to fix upon the place, which was to be the identical spot where he had received his wound, while about to scalp the man whom he had shot in the field, just as he was raising the scalp halloo, twisting his hand in the hair of the head, and brandishing the scalping-knife. It is to be presumed that the guard may be said to be off their guard somewhat on account of the lameness of the prisoner, and the seeming impossibility that he could escape; but so it was, that while engaged in conversation on the burning that was to take place, or by some other means inattentive, he had climbed up at the remote corner of the blockhouse, where he was, and got to the joists, and thence upon the wall-plate of the blockhouse, and thence as was supposed got down on the outside between the roof and the wall-plate; for the blockhouse is so constructed that the roof overjuts the wall of the blockhouse, resting on the ends of the joists that protrude a foot or two beyond the wall, for the purpose of those within firing down upon the Indians, who may approach the house to set fire to it, or attempt the door. But so it was that, towards morning, the Indian was missed, and when the jury met, there was no Indian to be brought before them. Search had been made by the guard everywhere, and the jury joined in the search, and the militia went out in all directions, in order to track his course and regain the prisoner. But no discovery could be made, and the guard were much blamed for the want of vigilance; though some supposed that he had been let go on the principle of humanity that they might not be under the necessity of burning him.

The search had been abandoned, but three days, when a lad looking for his horses, saw an Indian with a pole or long stick, just getting on one of them by the help of a log or trunk of a fallen tree; he had made a bridle of bark as it appeared which was on the horse's head and with which and his stick guiding the horse he set off at a smart trot, in a direction towards the frontier of the settlement. The boy was afraid to discover himself, or reclaim his horse, but ran home and gave the alarm, on which a party in the course of the day was collected and set out in pursuit of the Indian. They tracked the horse until it was dark, and were then obliged to lie by; but in the morning, taking it again, they tracked the horse as before, but found the course varied taking into branches of streams to prevent pursuit, and which greatly delayed them, requiring considerable time tracing the stream and to find where the horse had taken the bank and come out; sometimes taking along hard ridges, though not directly in his course, where the tracks of the horse could not be seen; in this manner he had got on to the Allegheny river where they found the horse with the bark bridle, where he appeared to have been left but a short time before. The sweat was scarcely dry upon his sides; for the weather was warm and he appeared to have been ridden hard; the distance he had come was about ninety miles. It was presumed the Indian had swam the river, into the uninhabited (and what was then called the Indian) country, where it was unsafe for the small party that were in pursuit to follow.

"After the war, I took some pains to inform myself whether he had made his way good to the Indian towns, the nearest of which was Sandusky, at the distance of about two hundred miles; but it appeared that after all his efforts, he had been unsuccessful, and had not reached home. He had been drowned in the river or famished in the woods, or his broken limb had occasioned his death."

The following account written by Ephraim Douglass at Fort Pitt (see Penn. Mag. of Hist. and Biog., Vol. i, pp. 46-48), gives particulars, also, of the escape of the "Pet Indian:""Pittsburgh, July 26, 1782.

"My Dear General: Some three months ago, or thereabouts, a party of Indians made a stroke (as it is called in our country phrase) at a station [Walthour's] distinguished by the name of the owner of the place, Wolthower's (or as near as I can come to a German name), where they killed an old man and his Sons, and captivated [captured] one of his daughters."This massacre was committed so near the fort that the people from within fired upon the Indians so successfully as to wound several and preventing their scalping the dead. The girl was carried to within six miles of this place, up the Allegheny river, where her bones were afterward found with manifest marks on her skull of having been then knocked on the head and scalped. One of the Indians who had been wounded in the leg, unable to make any considerable way and in this condition deserted by his companions, after subsisting himself upon the spontaneous productions of the woods for more than thirty successive days, crawled into this village in the most miserable plight conceivable. He was received by the military and carefully guarded till about five days ago, when, at the reiterated request of the relations of those unfortunate people whom he had been employed in murdering, he was delivered to four or five country warriors deputed to receive and conduct him to the place which had been the scene of his cruelties, distant about twenty-five miles. The wish, and perhaps the hope of getting some of our unfortunate captives restored to their friends for the release of this wretch, and the natural repugnance every man of spirit has to sacrificing uselessly the life of a fellow-creature whose hands are tied, to the resentment of an unthinking rabble, inclined the general to have his life spared, and to keep him still in close confinement. He was not delivered without some reluctance, and a preemptory forbiddance to put him to death without the concurrance of the magistrate and most respectable inhabitants of the district: they carried him, with every mark of exultation, away. Thus far, I give it to you authentic; and this evening, one of the inhabitants returned to town, from Mr. Wolthower's neighborhood, who finishes the history of our pet Indian (so he was ludicrously called) in this manner: That a night or two ago, when his guards, as they ought to be, were in a profound sleep, our Indian stole a march upon them and has not since been seen or heard of.

"I may perhaps, give you the sequel of this history another day; at present, I bid you good-night; my eyes refuse to light me longer."

"Pittsburgh, 4th of August, 1782.

"Dear Sir: To continue my narrative—our pet Indian is certainly gone; he was seen a day or two after the night of his escape very well mounted, and has not since been seen or heard of; the heroes, however, who had him in charge, or some of their friends or connection, ashamed of such egregious stupidity, and desirous of being thought barbarous murderers rather than negligent block-heads, have propagated several very different reports concerning his supposed execution, all of them believed to be as false as they are ridiculous.

"EPHRAIM DOUGLASS.

‘To Gen'l William Irvine."The following was the order issued by Irvine:

"You are hereby enjoined and required to take the Indian delivered into your charge by my order, and carry him safe into the settlement of Brush creek. You will afterwards warn two justices of the peace, and request their attendance at such place as they shall think proper to appoint, with several other reputable inhabitants. Until this is done and their advice and direction had in the matter, you are, at your peril, not to hurt him nor suffer any person to do it. Given under my hand at Fort Pitt, July 21, 1782.

"To Joseph Studibaker, Francis Birely, Jacob Randolph, Jacob Birely, Henry Willard, and Frederick Willard."

______

POMEROY OR POMROY'S BLOCKHOUSE.

In the Derry settlement of Westmoreland county there were several stronghouses which were constantly kept ready for emergencies and to which settlers sometimes fled for protection. One of these was the house of Col. John Pomroy, a man highly spoken of by his neighbors and commended by those in authority for the performance of the official duties entrusted to him. He held a colonel's commission during the Revolution in the militia service, and was engaged in many of the short campaigns. His house stood about a mile from Barr's Fort, and a little off the line from the point to Wallace's Fort. The farm on which it stood is now, owned by Mr. John C. Walkinshaw, and is about one-half a mile from Millwood Station (on the Penn'a railroad) towards New Derry village, on the main road.

______

WILSON'S BLOCKHOUSE.

Of like character to Col. Pomroy's domicile was that of Major James Wilson, also of the Perry settlement. This is now in the ownership of Mr. Benjamin Ruff's estate, and the farm is about a mile from New Perry village northeastward, and would be a little to the right, going from Barr's to Wallace's.

______

RUGH'S BLOCKHOUSE.

Michael Rugh came into Westmoreland in 1782 from Northampton county, Penna. He early built a large two-story log-house a little south of the present barn and a little above the spring on the farm now owned by Mr. John Rugh, a grandson of Jacob Hugh, third son of Michael. The farm is situate in Hempfield township, Westmoreland county, in what has long been known as the Rugh settlement, about two miles south of Greensburg, and near the County Home.

This house was what was regarded as "very large and strong, with holes to shoot through." What was left of the house was torn down in 1842, and up to that time it bore marks evident of the use to which it was in part intended.Michael Rugh was a man of some prominence, especially in the latter part of the Revolution. He was elected Coroner in 1781, and was also, later in the same year, one of the Commissioners of Purchases, (Arch., iii, 176, 2d Ser.), and a Common Pleas Judge in 1787, (Rec., xv, 269).

Rugh's Blockhouse—probably the large house referred to specially fitted for defense—was a designated point where supplies were delivered and kept for distribution throughout the latter part of the War. Michael Huffnagle, the contractor for supplying the post of Fort Pitt with provisions, proposed to the Council, Dec. 20, 1781, "to supply the militia and ranging company for Westmoreland county, the ration to consist of the same article as for the continental troops, and to be paid for at the same rate, which is eleven pence half penny for every ration, in gold or silver,—to be delivered at Hannastown and Ligonier; and twelve pence per ration at Rook's [Rugh's] Blockhouse (Washington-Irvine Cor., 161, note.) This proposal is made through Christopher Hayes, Esq., Member of the Council from Westmoreland county."

What was known as the "old barn" on this farm is described by the older members of the Rugh family as a very large building built of large logs divided into four compartments, with holes commonly called port-holes in the walls. This building, we take it, was the remains of the structure erected for the storage of the supplies which were delivered here; and it might have been intended for harborage, as well. The structure was an uncommon one; and this fact well established by direct personal knowledge, taken in connection with other well known facts, such as those above referred to, would allow this circumstantial evidence to have the weight of positive proof.

There is an unbroken tradition of the people's fleeing to Rugh's Blockhouse from all the surrounding country after the attack on Hannastown. The place was well known, much frequented, and, beyond doubt, was a harborage on that occasion.

Rugh's name is spelled variously both in official documents and in correspondence. It takes on such forms as Rugh, Ruch, Rough, and Rook. (See note to Hannastown—Michael Huffnagle's letter dated Fort Reed, July, 1782.)

______

FORT ALLEN. (HEMPFIELD TOWNSHIP.)

Fort Allen was the name given to a structure erected in "Hempfield township, Westmoreland county, between Wendel Oury's and Christopher Truby's," at the same time that Fort Shippen at Capt. John Proctor's, Shields Fort and others of like character were erected, that is, in the summer of 1774. This structure was probably a stronghouse, or a blockhouse erected for the emergency and never required, so far as is known, for public use. It was named probably in honor of Andrew Allen, Esq., of the Supreme Executive Council. From the names of the signers, the locality was manifestly in the German settlement of Hempfield township to the northwest of Greensburg. No other mention of this place by that name is found. (See Rupp's West. Pa., Appx.) All knowledge of its exact location has passed away.

______

KEPPLE'S BLOCKHOUSE.

What was known as Kepple's Blockhouse was located on the farm of Michael Kepple in Hempfield township, Westmoreland county, about a mile and a half from Greensburg on the road leading to Salem (Delmont, P. O.) It was a stronghouse built of hewn logs on a stone foundation with loop-holes for rifles, and with all the exposures well protected by heavy planking. It was occupied as the residence of the owner, but was resorted to by neighbors during the incursions of 1781-2. The farm is now owned by Mr. Samuel Ruff, whose wife, Sibilla was a daughter of Jacob Rugh, whose wife was the daughter of Michael Kepple, former owner. The remains of this stronghouse were still standing within living recollection. Some of the logs with notches in them which were intended for portholes, may still be seen in a building on the place used for corncrib.

______

STOKELY'S BLOCKHOUSE.

A blockhouse erected on the farm of Nehemiah Stokely, and called Stokely's Blockhouse, was well known and much frequented during the Revolution. It was located on the Big Sewickley creek within about a half mile of Waltz's mill, earlier called Carr's mill. It stood on an elevated ground from which one could see quite a distance round, excepting on the northward on which side there was a hill. The building was two-storied, the timber was all whipsawed, and its sides were covered, at least in part, with heavy boards; the roof was shingled and fastened with hammered nails made by the blacksmith.

A man by the name of Chambers was captured near this blockhouse by the Indians; he returned after a captivity of several years. The people about this blockhouse were much harrassed during the summer of 1782, and an armed force was kept constantly during that time at this blockhouse. [David Waltz, Esq., Waltz's Mill, Pa. MS.]

______

McDOWELL'S BLOCKHOUSE.

A blockhouse or stronghouse stood at a point in the village of Madison, Hempfield township, near one of the angles at the crossing of the Greensburg and West Newton road and the Clay pike from Somerset westward, on land now owned by Thomas Brown, called McDowell's Blockhouse, after the first occupant of the land. The late James B. Oliver, Esq., of West Newton, father of Mrs. Edgar Cowan, widow of the Hon. Edgar Cowan, U. S. Senate, was born here, whither his parents had fled a few days before that event, for protection from the Indians. Mr. Oliver was born in 1781. This land was at that time in the nominal occupancy of Thomas Hughes and was sometimes called Hughes. It adjoined land of James Cavett, (Cavet), one of the commissioners with Robert Hanna to locate a county town at the time of the organization of the county, and passed to him in 1786, to whom it was surveyed in the name of Thomas Hughes. It was within the limits of the Sewickley settlement.

______

MARCHAND'S BLOCKHOUSE.

What was called a blockhouse, but what was probably a stronghouse which was situated on what was better known as the Doctor David Marchand farm, on the north fork of the Little Sewickley in Millersdale, Hempfield township, about four miles southwest of Greensburg, has been connected with the Revolution as a place of refuge against the Indians. Rev. Cyrus Cort, of Wyoming, Delaware, writes: "It is one of the traditions of our family that my great grandfather, John Yost Cort, had charge, in perilous times, of the women and children in that fort. " (M. B. Kifer, Esq., of Adamsburg, Pa., furnishes MS. authorities.)

______

FORT SHIPPEN, AT CAPT. JOHN PROCTOR'S.

Among the petitions sent to the Governor in 1774, incident to the apprehension of an Indian war, was one from "Fort Shippen, at Capt. John Proctor's." (Arch., iv, 534.) The petition sets forth, in part, "That there is great reason to fear that this part of the country will soon be involved in an Indian war. That the consequences will most probably be very striking; as the country is in a very defenseless state, without any places of strength or any stock of ammunition or necessary stores. * * * In these circumstances, next to the Almighty, they look to your Honour and hope you will take their case into consideration, and afford them such relief as your Honor will see meet."

The structure was named doubtless in honor of Edward Shippen, Esq., one of the Council.

John Proctor was a very conspicuous man in the early history of the county. He was commissioned to various offices by the Penns, which he held in Cumberland and Bedford counties, prior to the erection of Westmoreland. He was the first sheriff of Westmoreland county; took an active part in the affairs of 1775 at the outbreak of the Revolution; was Colonel of the First Battalion of Associators organized in pursuance of the Resolutions of 16th of May, 1775, at Hannastown. The flag of the battalion—a rattlesnake flag—is still in possession of Mrs. Margaret Craig of New Alexandria, Pa. He raised a company of riflemen in the early summer of 1776 with Van Swearingen, and joined the continental army with it where he served with Washington for a short campaign. He then returned to Westmoreland; was a strong candidate for Colonel of the battalion authorized by Congress to be raised in Westmoreland and Bedford, but was unsuccessful, Col. Mackay being selected for that office; was appointed pay master of the militia of Westmoreland county, Sept. 13, 1776, and, shortly after, with Thomas Galbraith, was appointed commissioner in pursuance of an ordinance passed by the Council of Safety, Oct. 21st, 1777, to seize upon the personal effects of those who had deserted to the King of Great Britain. General William Irvine, Commander of the Western Department, addressed a letter to Col. John Gibson from "Proctor's," Jan. 1782. (Wash.-Irv. Cor., 349.)

Proctor was a neighbor of Col. Archibald Lochry, Lieutenant of the County; his place of residence was in Unity township near a stream called Twelve Mile Run, about three miles from Latrobe, and seven miles from Hannastown. It was not far from the Forbes Road. The structure called Fort Shippen was erected probably in the early part of the summer of 1774, as on June 3rd it is reported "many families [about Hannastown] returning to this [eastern] side of the mountains, others are about building of forts in order to make a stand," (Arch., iv, 505), and "a fort is to be built at Capt. John Proctor's" (Arch., iv, 507). By the directions and authority of Arthur St. Clair, during that season, twenty men were stationed here. (Arch., iv, 504.) It is probable the place was frequently resorted to during the Revolution in time of excitement and fear, although no public or other mention is made of the blockhouse or stronghold after the period of its erection; but "Proctor's" is mentioned frequently.

______

LOCHRY'S BLOCKHOUSE.

Reference is sometimes made in the Archives to Lochry's Blockhouse. This structure was built on the farm occupied by Col. Archibald Lochry, the County Lieutenant, whose farm was situate on a small stream called the Twelve Mile run, from which he sometimes dates his correspondence. This stream joins another called the Fourteen Mile run which empties into the Loyalhanna about a mile eastward of Latrobe. The residence of Lochry would be now in Unity township, near the turnpike from Youngstown to Greensburg on the right hand side going in that direction and between the turnpike and St. Vincent's Monastery.

Col. Lochry in a letter to President Reed dated April 17th, 1781, (Arch. ix, 79), recounts the circumstances which impelled him to erect this building. He says: "The savages have begun their hostilities; since I came from Phila., they have struck us in four different places—have taken and killed thirteen persons with a number of horses and other effects of the inhabitants. Two of the unhappy people were killed one mile from Hannastown. Our country is worse depopulated than ever it has been. * * * There is no ammunition in the country, but what is public property; when the Hostilities commenced, the people came to me from all Quarters for ammunition, and assured me that if I did not supply them out of the public magazine, they would not attempt to stand. Under the Circumstances I gave out a large Quantity, and would be glad to have your Excellencies approbation, as I am certain this County would have been evacuated had I not have supplied them with that necessary.

"I have built a magazine for the state stores, (in the form of a Blockhouse) that will be defended with a very few men. I have never kept men to guard it as yet, and will be happy to have your Excellencys Orders to keep a Sergeants Guard at our small magazine, the consequence of moving to the interior parts of the Country would discourage those people on the Frontiers who have so long supported it."

To this communication President Reed replied, May 2d, 1781, (Arch. ix, 115.). "With Respect to Ammunition we have had the greatest Difficulty to procure it, there not being one thousand pounds of Lead in this City (Phila.). You and the Gentlemen of the County will therefore see the indispensible Necessity of using it with Frugality and preventing all Waste. * * * * With Respect to the Magazine built near your House, Council do by no means approve of it, as they think the collecting all the ammunition at one Place is exposing it to the Enemy, and they do not wish to encourage the erecting Buildings without being previously consulted. Instead, therefore, of keeping the whole ammunition at one Place, we would choose it should be kept at sundry Places. The establishing a Serjeant's Guard therefore appears unnecessary."

Of this blockhouse we have found no further mention. At that very time Col. Lochry was making arrangements to gather a force of Westmorelanders to co-operate with General George Rogers Clark in his projected expedition against the Indians in the northwest. It was Lochry's hope that by distressing the savages by means of an active campaign carried on against them in their own country, some relief might be brought to the afflicted frontiers of that county which he had served so long and so well. That he was harassed and distressed and worried beyond all measure in the performance of his official duties, there can be no doubt; as his correspondence preserved in the Archives abundantly shows. Later in the season he left with the forces which he had gathered together to join Clark at Wheeling. He never returned. With him perished the most of his men—among whom were many of the best frontiersmen of the county.

______

PHILIP KLINGENSMITH'S HOUSE

Col. James Perry writes to president Reed from "Westmoreland County, Savikley [Sewickley], July 2d, 1781," (Arch. ix, 240) :—"This morning a small garrison at Philip Clingensmith's (Klingensmith's), about eight miles from this, and four or five miles from Hannastown, consisting of between twenty and thirty men, women and children was destroyed; only three made their escape: The particulars I cannot well inform you, as the party that was sent to bury the dead are not yet returned, and I wait every moment to hear of or perhaps see them strike at some other place. The party was supposed to be about seventeen, and I am apt to think there are still more of them in the settlements."

James Perry was one of the eight delegates that Westmoreland sent to the Convention which met at Philadelphia, July 15th, 1776, to frame a constitution. He was a colonel of militia and an active citizen during all these times. In 1781 was a commissioner of supplies. He resided in the Sewickley settlement in Westmoreland county.

The Klingensmiths belonged to what is called the Brush creek, and sometimes the Manor, settlement; and although the exact location of Philip Klingensmith's house is unknown, it is certain that his place was a favorable one for the settlers thereabout. Philip Klingensmith with his family, of which Peter Klingensmith was one, were early settlers; their names being among those who signed the petition to Governor Penn in 1774, headed at "Fort Allen, Hempfield Township, between Wendel Oury's and Christopher Trubee's." The name is there spelled Klingelschmit; and his neighbors were Peter Wannemacher, Adam Bricker, the Altmans, Baltzer Moyer, Jacob Heuser, and others whose names are familiar in that region and who were of German lineage. The name is also associated with the Byerleys, the Walthours, and others with whom they were connected by marriage. The place was sometimes called Fort Klingensmith, (see "Col. Henry Bouquet and His Times" by Rev. Cyrus Cort, p. 92.). It is probable that the old house stood somewhere on the farm now owned by Daniel Mull, in Penn township, Westmoreland county, about three miles northeast of Manor station on the Pennsylvania railroad, about one and a half miles northwest of Harrison City village, and about half a mile westward from Brush creek. This supposition is founded on the line of title to lands which about that time were in the seizin of Philip Klingensmith. This situation was on the line of the Brush creek settlement and was an exposed one. While the tradition is a pronounced one in all the neighborhood that the Klingensmith house was what is usually called a blockhouse, there is no positive assurance derivable from any source as to its exact location. On this point we would not, therefore, assert a positive opinion, for there are some who believe that the location of the house was on what is best known as the Bigelow farm, which is now on the northeastern margin of the borough of Jeannette, and about a mile from the Pennsylvania railroad, on the old road from Greensburg. This was one of the Klingensmith farms, of which there were a number. Although diligent inquiry was made, no information more definite than this given, has been obtained. The traditions of the place vary. This last point would be near two miles from the former.

The Brush creek settlement suffered much from Indian depredations from an early day. On the 26th of Feb., 1769, "about twenty miles east of Pittsburgh, on the main road leading over the mountains, eighteen persons—men, women and children— were either killed or taken prisoners." Such marauds were distressingly frequent—especially in 1781 and 1782. It had become the custom of the Commandants at Fort Pitt to send out small squads of soldiers to protect the inhabitants while, they gathered in the harvest. (See Walthour's Fort.) In the letter of Col. Perry, quoted above, he speaks of a small garrison there at the time. It may be inferred that the unusual number of people there was incident to the gathering of the harvest, as well as to the terror of the times. Col. Lochry writes July 4th, 1781, (Arch. ix, 247), "We have very distressing times here this summer. The enemy are almost constantly in our county killing and captivating the inhabitants."

______

GASPARD MARKLE'S HOUSE AND STATION.

Gaspard Markle in 1770 removed from Berks county, Pa., to Westmoreland. From a biographical sketch prepared from data furnished by his descendants it is said that "for several years after the settlement of the family in Westmoreland the neighboring settlements on the Allegheny and Kishkiminetas were harassed by the Indians, and the residence of Gaspard Markle was the post of refuge to which the settlers fled for succor and safety." Gaspard Markle was the ancestor of the Markle family long identified with the financial and political affairs of Western Pennsylvania. His house stood on the Sewickley creek in South Huntingdon township, about two miles from (now) West Newton. The present owner is George W. Markle. Markie's Mills were among the oldest in Western Pennsylvania, built as early as 1772. The forces of Col. Lochry in his expedition of 1781 to join Clark, made this place an objective point, and the last letter of Lochry to President Reed is dated from Miracle's [Markle's] Mill, Aug. 4th, 1781 (Arch. ix, 333)—properly called "Maracle's Mill" in the Journal of Lieut. Isaac Anderson (Arch. xiv, 685, 2nd Ser.).

"Markle's," is spoken of late in the Revolution, and sometimes it is referred to as Markle's Station. It was a part of the Sewickley settlement, the people of which were to a great extent mutually dependent on each other. At times many families were gathered together here. Among the first settlers hereabout were the Simralls, the Blackburns, the Fultons, Isaac Robb. Somewhat later George Plumer located in that neighborhood. Jonathan Plumer, his father, was a Commissary in Braddock's Expedition, (1755), and in 1761 he made improvements near Fort Pitt by permission of Col. Bouquet. His son, George Plumer, was born on this improvement in 1762. He is said to have been the first child born of British-American parents in the British Dominions west of the Allegheny Mountains—that is after this portion of the country had been adjudged by the treaty of peace to England. This treaty of peace was signed at Fontainebleau, Nov. 3d, 1762, and Geo. Plumer was born Dec. 5th, of the same year. He died June 8th, 1843.

______