REPORT OF THE COMMISSION TO LOCATE THE SITE OF THE FRONTIER FORTS OF PENNSYLVANIA.

VOLUME TWO.

CLARENCE M. BUSCH.

STATE PRINTER OF PENNSYLVANIA.

1896.

THE FRONTIER FORTS OF WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA.

Pages 39-99.

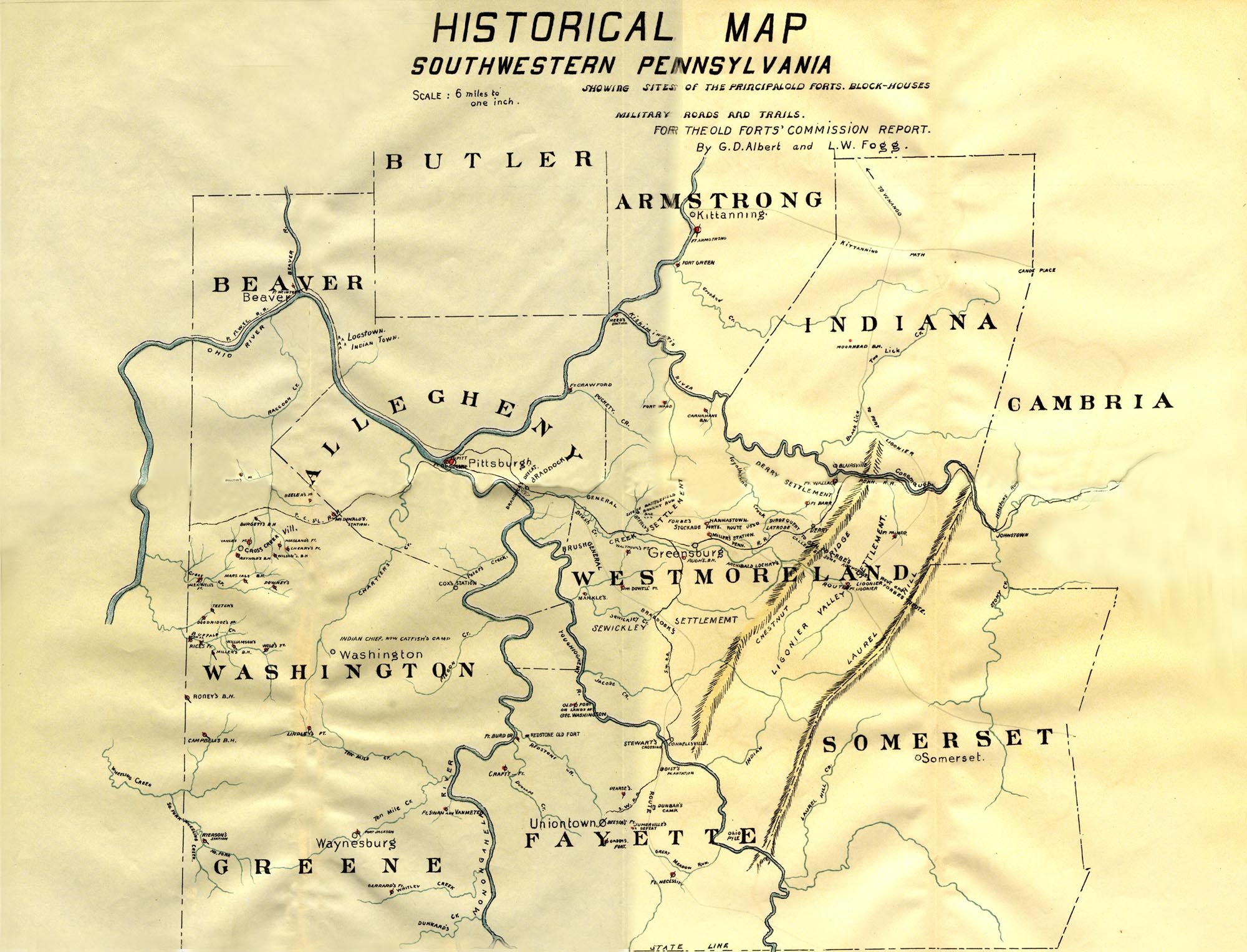

By George Dallas Albert.

Historical Map of Southwestern Pennsylvania, by G. D. Albert & L. W. Fogg

of the Old Forts' Commission Report. Enlarge in browser.

FORT DUQUESNE.

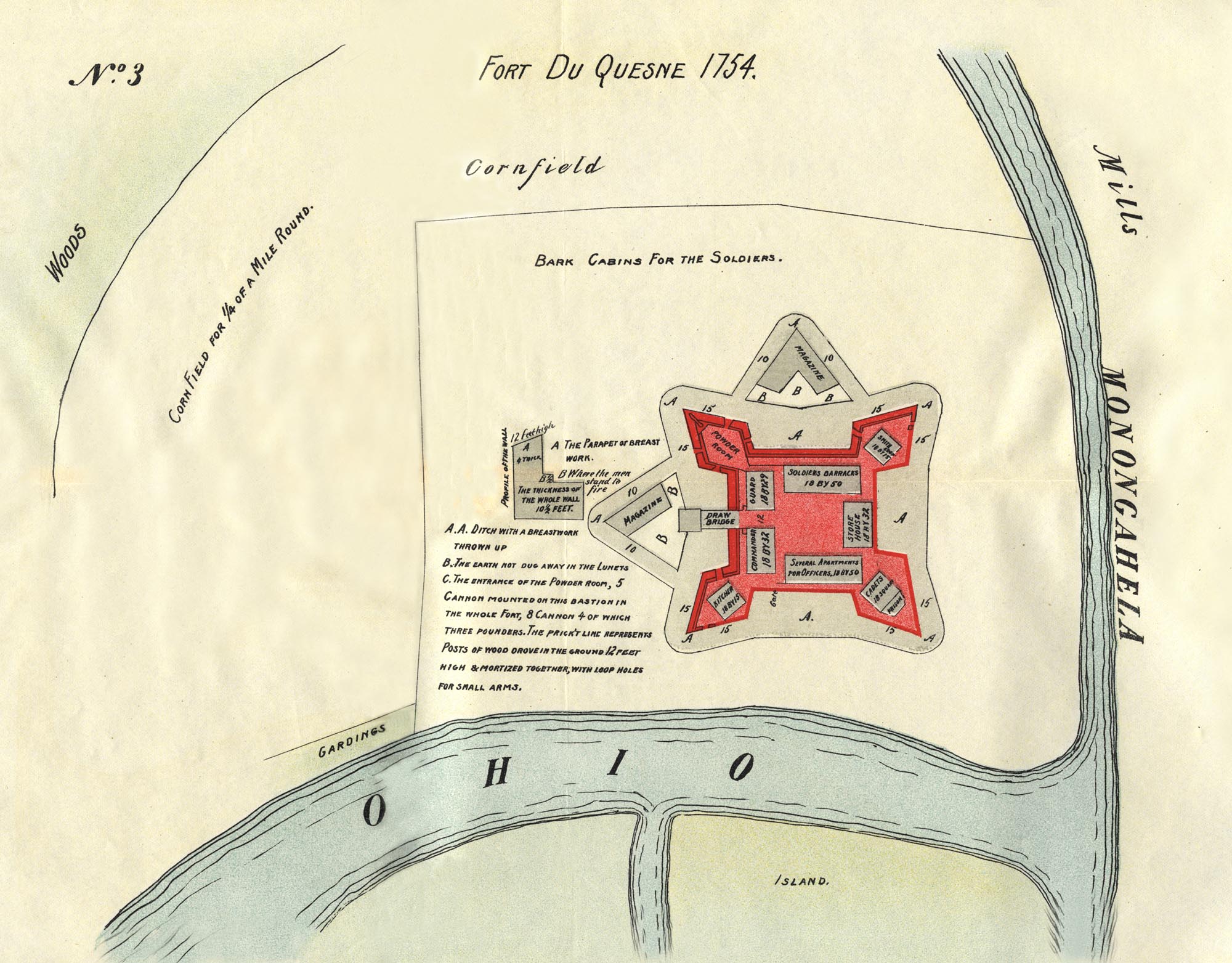

Illustration of Fort Du Quesne, 1754. Enlarge in browser.

Numbered notes expounded in section on Fort Fayette.

Capt. William Trent, holding his commission from Governor Dinwiddie of Virginia, began the erection of a fort at the Forks of the Ohio river, (1) under the auspices of the Ohio Company, on Sunday, Feb. 17th, 1754. (2.) The fort was not yet completed, when the French under Contrecoeur, (3) April 16th, 1754, appeared in sight, coming down the Allegheny river, in large numbers. They landed from their boats, drew up on the shore, and Le Mercier, commander of the artillery, with two drummers, one of them as an interpreter for the French, and a Mingo Indian, called The Owl, as an interpreter for the Indians, was sent by his superior to demand the surrender of the post. (4.) Capt. Trent and Lieut. Frazer being absent, Edward Ward, Ensign, in command, the fort was by him given over to the French. Their object in descending the rivers from Canada was to secure this post and to erect thereat a fortification, regarding it within the limits of their territory of Louisiana. (6.)

They immediately erected a fortification which was strengthened as time went on and the danger of attack increased. It was called Fort Duquesne, in honor of the Governor-General of Canada. (7.) It was probably completed early in the summer, (8) but in the papers submitted herewith its condition at various times will be noted. It was located in the Point, at the extreme end of the neck of land between the rivers, upon plans made by M. de Chevalier de Mercier, captain of artillery who had been the designer and engineer of a number of such like fortifications for the French in their Canadian possessions. He is represented as an officer of considerable ability, but a leech on the public purse; one of the large class who came to the New World with the determination of getting rich at any cost.

It was understood that this overt act of war would be followed by prompt action on the part of England, and the colonies, especially that of Virginia. Already a force of volunteer militia had been called out by the Governor of Virginia for the special purpose of aiding the Ohio Company to retain this post. Some of these were on the way and were west of Wills creek when Trent was forced to surrender. It was learned by the French through the active agency of their Indian allies and the vigilant efforts of their own soldiers that the Virginians, notwithstanding this backset, were advancing toward this point with the evident intention of fighting for it. Small detachments were thereupon sent out from the fort to harass and impede the little army which, under young Washington was proceeding on the trail made by the Ohio Company the year previous, and on the Indian path which led from the termination of that trail westward. (9.)

Captain Trent had been directed by the Governor of Virginia to occupy this point directly after he was assured of intentions of the French from the report of Washington. Trent's small detachment was therefore merely the advance of a stronger force which was authorized by the Virginia authorities to proceed westward as soon as organized and equipped, to occupy this and other posts which were expected to be established. This force, however, could not be raised and equipped immediately, but the work of doing so progressed as circumstances permitted. The Virginia Assembly voted a thousand pounds towards supporting the expedition and authorized more men to be raised. Colonel Joshua Fry, an English gentleman, was to be in chief command; Washington, whose commission had been advanced to that of lieutenant-colonel, was second in command. Ten cannon and other military equipments which had arrived recently from England, were sent to Alexandria for the use of the expedition. (10.)

Washington, with two companies which he had raised by his individual exertions, marched from Alexandria on the 2nd of April, 1754, and arrived at Wills Creek (Cumberland, Md.), April 17th. He had been joined on his way by Captain Stephen. His forces amounted to one hundred and fifty men. Here he learned of the surrender of Trent. At a council of war it was concluded that it would be impossible to attack successfully the fort occupied by the French, without reenforcements; but it was determined pursuant to the instructions which had been given by Governor Dinwiddie in contemplation of this event, to proceed to the store-house which had been erected for the Ohio Company the year previous at the mouth of Redstone creek on the Monongahela (Brownsville). This point was regarded a favorable one for operations against the fort at the Forks. With this object he proceeded forward, opening the road where necessary and taking such precautions as the occasion required. Having effected the crossing of the mountain ranges with difficulty, he reached the Youghiogheny where he was delayed until he constructed a bridge for its passage. Learning that the French had sent out a force to oppose him – which force was largely in excess of his own – he hastened forward to the Great Meadows, at which place he erected Fort Necessity. The events which have been narrated elsewhere more in detail, then followed. The first collision between the French and Virginians occurred when Washington, guided and aided by the friendly Indian, Tanacharison, called otherwise, Half-King, on the morning of the 28th of May, 1754, surprised and attacked Jumonville with his party who had been sent out to spy his movements and to intercept his progress. It is a circumstance to be noted that while the dispossession of the Virginians from the Forks of the Ohio has been generally recognized as the beginning of that colossal and eventful war which was so fatal to the power and glory of France throughout the world, and especially in America, yet no less noteworthy is the fact that the first gun fired in the first collision of arms was by the order of Washington and under his immediate command.

Thence followed the affair of Fort Necessity itself, the result of which left the French in undisputed possession of Fort Duquesne and of the region of country which it controlled.

It was with truth related at the time, that the events which then transpired in the vicinity of Fort Duquesne were talked of in Paris, and that the name of Washington was then heard first in Europe.

The French did not underestimate the importance of this post, or the necessity of holding it at all hazards. Its garrison from the first was large; and it became immediately upon its occupancy the chief post on their line of frontier from Lake Erie southward. This importance it maintained as long as it was under their domination.

To make themselves more secure the French worked on the Indians of this region by every device. They were eminently successful in their dealings with them, and they had little trouble to make them their allies and dependants. There had grown a feeling of distrust on the part of the Indians of the Virginians and an antagonism against them by the tribes along the rivers; they were losing their ancient regard for the Pennsylvanians on account of the manner in which they had been duped out of their hunting-grounds, and they were thus the more easily prevailed upon by plausible argument and by substantial evidence of friendship, to become the allies of the French. Many tribes were sustained by bountiful donations; the post was frequented by chiefs and warriors who came from distant tribes, and quite a settlement of natives was gathered in huts around the Fort, to whom were served rations from the public stores. To this point the representatives of the tribes came and were here fed in time of need. Here traders and governmental agents carried on the, exchange of furs and peltry; and from here went forth those predatory bands, sometimes led by Frenchmen or Canadians, which carried terror, destruction and death to the border settlements of Pennsylvania, Virginia and Maryland. To here were carried the captives taken in these ventures, whence they were from time to time sent to other posts, or to Canada. And this continued as long as the place remained in their possession; that is to say, from the time of its occupancy in the spring of 1754 until its abandonment on the approach of the army under Forbes, in the fall of 1758. (11.)

The history of this post under the French is to be learnt largely from the documents which relate to the military affairs of French-Canada, from the accounts which from time to time, were detailed by escaped captives, or from statements made by captured prisoners. As these documents are brought to light, more information is being obtained; and doubtless the time will come when a most satisfactory account can be given of its history in detail.

The first description we have of the fort is that by Captain Robert Stobo, one of the two hostages given by Washington at the surrender of Fort Necessity, who was taken by the French to Fort Duquesne, from where, after being detained for some time, he was sent into Canada, but ultimately returned to Virginia. (12.)

Stobo, shortly after his capture, wrote two letters to the Governor of Virginia, which were entrusted to two friendly Indians, and each was safely delivered. He enclosed the plan of the fort; and this plan and the description of it furnished by him were regarded, from a military point of view, as of great value. They were carefully kept and were given to Gen. Braddock when he took command of the expedition against Fort Duquesne, and they were found among his effects on the field of battle, and with other papers were forwarded by the French authorities to the proper depository of such official documents in Canada. (13.) In the letter of July 28th, 1754, after speaking of the affairs of the neighboring Indians, he says: "On the other side, you have a draft of the Fort, such as time and opportunity would admit of at this time. The garrison consists of two hundred workmen, and all the rest went in several detachments to the number of one thousand, two days hence. Mercier, a fine soldier, goes; so that Contrecoeur, with a few young officers and cadets, remain here. A lieutenant went off some days ago, with two hundred men, for provisions. He is daily expected. When he arrives, the garrison will. La Force is greatly wanted here – (14) no scouting now. He certainly must have been an extraordinary man amongst them – he is so much regretted and wished for."

In the letter of July 29th, he says: "'There are about two hundred men at this time, two hundred more expected in a few days; the rest went off in several detachments to the amount of one thousand, besides Indians. The Indians have great liberty here; they go out and in when they please without notice. If one hundred trusty Shawanese, Mingoes and Delawares were picked out, they might surprise the fort, lodging themselves under the platform behind the palisades by day, and at night secure the guard with the tomahawks. The guard consists of forty men only, and five officers. None lodge in the fort but the guard, except Contrecoeur, the rest in bark cabins around the fort."

A description of the fort as it was in the summer of 1754 is given by Thomas Forbes, a French soldier who was at the fort at that time, and is as follows:

"At our arrival at Fort DuQuesne (from Le Boeuf) we found the Garrison busily engaged in compleating that Fort and Stockadoing it round at some distance for the security of the Soldiers Barracks (against any Surprise) which are built between tile Stockadoes and the Glacis of the Fort.

"Fort Du Quesne is built of square Logs transversely placed as is frequent in Mill Dams, and the Interstices filled up with Earth; the length of these Logs is about sixteen Feet which is the thickness of the Rampart. There is a Parapet raised on the Rampart of Logs, and the length of the Curtains is about 3o feet, and the Demigorge of the Bastions about eighty. The Fort is surrounded on the two sides that do not front the Water with a Ditch about 12 feet wide and very deep, because there being no covert way the Musquetteers fire from thence having a Glacis before them. When the News of Ensign Jumonville's Defeat reached us our company consisted of about 1,400. Seven hundred of whom were ordered out under the command of Captain Mercier to attack Mr. Washington, after our return from the meadows, a great number of the Soldiers who had been labouring at the Fort all the Spring were sent off in Divisions to the several Forts between that and Canada, and some of those who came down last were sent away to build a Fort some where on the head of the Ohio, so that in October the Garrison at Du Quesne reduced to 400 Men, who had Provisions enough at the Fort to last them two years, notwithstanding a good deal of the Flour we brought down in the spring proved to be damaged, and some of it spoiled by the rains that fell at the Time. In October last I had an opportunity of relieving myself and retiring, there were not then any Indians with the French but a considerable number were expected and said to be on their march thither." (15.)

When the advance of the Virginians was repelled after the capture and occupancy of the place by Contrecoeur, the forces were moved about; some were sent to Niagara and others to points along the Allegheny and Ohio. The force here was ample, although it differed at times. Francis Charles Bouviere, a deserter from the French fort at Niagara, in a deposition made the 28th of December, 1754, stated that he had served with other soldiers in the garrison at Quebec until the beginning of the last winter, when he embarked along with six hundred men, Canadians and soldiers, on the expedition against the English at Ohio, and then after attacking and taking the fort which the English had begun, their commander, Contrecoeur, ordered four hundred men, of which he was one, to return to Niagara, detaining two hundred men with him in the fort. (16.)

Another deserter stated that he was one of a very large number of soldiers who had been brought over from France, the most of whom were sent to the French fort commanded by Contrecoeur, on the Ohio; that the soldiers after their arrival were employed in digging mines in order to blow up the English on their approach to attack them, and that they talked of making mines all about the fort at a great distance; that the French had heard the English were making great preparations against them; that there were numbers of French Indians in the camp with the French who spoke French, and were extremely attached to them; that the French said they would by force compel the English to join with them; that they offered the lands about the fort to the Canadians and soldiers, and gave seed for their encouragement to settle there, and that there were about forty families who had accepted the terms and were settling the lands. (17.)

During the summer and fall of 1754, the frontiers were kept in constant alarm at the prospects of attack from that quarter. (18.) The French would seem to have been very desirous that the reports of what they contemplated doing should be carried out from the fort, and care was taken not to allow the effect of these reports to suffer from want of exaggeration. The accounts on the part of the French coming from various sources differ; and it will readily be admitted that many of them are not plausible.

George Croghan, Indian agent, reporting to Governor Hamilton, Sept. 27th, 1754, the result of his inquiries at that time, says: "I have had many accounts from Ohio all which agree that the French have received a reenforcement of men and provisions from Canada, to the fort in particular. Yesterday an Indian returned here, whom I had sent to the fort for intelligence; he confirms the above accounts and further says there was about sixty French Indians came there while he was there, and they expected better than two hundred more every day. He says that the French designed to send those Indians with some French in several parties to annoy the back settlements, which the French say will put a stop to any English forces marching out this fall to attack them. This Indian, I think, is to be believed, if there can be any credit given to what an Indian says." (19.)

In anticipation of an early campaign of the English and colonists, the force at Duquesne was very largely increased during the late fall of 1754. At one time it is probable there were at least one thousand regular soldiers there and several hundred Indians of various tribes. At the same time there were many other soldiers stationed at the forts up the Allegheny and on Lake Erie, ready for moving promptly when the occasion arrived.

Governor Sharp reports to Governor Morris from Annapolis, December 10th, 1754, as follows - "I acquaint you that I have just now received intelligence from Wills Creek, of the arrival of 1,100 French, and 70 Arondacks at the French on Monongahela, and that there are 400 French, and 200 Canawages and Ottaways more at the head of Ohio ready to come down thither. As soon as the Arondacks came to the Fort the Commandant divided them into three detachments, and sent them against the back settlements of Pennsylvania, Maryland or Virginia. (20.)

Croghan reports to Governor Morris, November 23rd. 1754, that "Four days ago an Indian man called Caughenstain, of the Delaware nation, who had been gone six weeks to the French fort as a spy, returned and brings an account that there was 1,100 French came to the fort on Ohio and 70 French Indians called Orundox, and that there was more French at the head of Ohio and 300 Indians of the Coniwagas and Outaways, which was expected every day when he left the Fort. They have brought eight more canoes with them. He says that the French sent out three small parties of Indians against the English settlements before he left that, but where they are destined he could not find out." (21.)

Governor Morris, speaking to the Assembly, December 3, 1754, refers to the condition of the Province as follows: "From the letters and intelligence I have ordered to be laid before you it will appear that the French have now at their Fort at Mohongialo above a thousand regular troops besides Indians; that they are well supplied with provisions, and that they have lately received an additional number of cannon; that their upper forts are also well garrisoned and provided." (22.)

This information was based probably on reports made some time prior thereto. When it became evident that no operations would be carried on that winter, most of the regular force was returned to Canada, leaving what was necessary for garrison duty. (23.) In April of 1755 there were said to be not two hundred French and Indians, and that their great dependence for the next summer seemed to be on the numerous tribes of Indians who had engaged to join them. (24.)

The aggressive campaigns on the part of the British which opened in 1755 against Niagara and Crown Point as well as Fort Duquesne, necessitated the retention in Canada of most of those forces which otherwise would have been sent to Duquesne. And therefore at no time after the fall or early winter of 1754 until after Braddock's defeat were the French forces so large there as they were shortly after its acquisition. They were then in expectation of a formidable movement on the part of the English. The number, however, was far in excess of that which was actually required; and upon the withdrawal of Washington and his Virginians after the surrender at Fort Necessity, there being then no immediate occasion for such a strong garrison, the men were temporarily withdrawn to other posts. But the invasion of territory which the British Government and its colonists asserted belonged to them, was a matter which the government of France knew would be the cause of war. And the event justified these anticipations.

From the State Papers pertaining to the government of Canada as a French province we get some information about affairs here at the time preceding the defeat of Braddock. The Marquis Duquesne to Vaudreuil, writing on the 6th of July, 1755, from Quebec, says: "By sieur de Contrecoeur's letter of the 24th of May last, the works of Fort Duquesne are completed. It is at present mounted with six pieces of cannon of six, and nine of two @ three pound ball; it was in want of neither arms nor ammunition, and since Sieur de Beaujeu's arrival, it must be well supplied, as he had carried with his brigade succors of every description.

"I must explain to the Marquis de Vaudreuil that much difficulty is experienced in conveying all sorts of effects as far as Fort Duquesne; for, independent of the Niagara carrying place, there is still that of Presqu'isle, six leagues in length; the latter fort, which is on Lake Erie, serves 815 a depot for all the others on the Ohio; the effects are next rode to the fort on the River au Boeuf, where they are put on board pirogues to run down to Fort Machault, one-half of which is on the River Ohio, and the other half in the River au Boeuf, and serves as a depot for Fort Duquesne. This new post has been in existence only since this year, because it has been remarked that too much time was consumed in going in one trip from the fort on the River au Boeuf to Fort Duquesne, to the loss of a great quantity of provisions which have been spoiled by bad weather. 'Tis to be hoped that, by dispatching the convoys opportunity [? opportunely] from Fort Machaults, everything will arrive safe and sound in twice twenty-four hours; besides it will be much more convenient at Fort Duquesne to send only to Fort Machaults for supplies.

"The Marquis de Vaudreuil must be informed that, during the first campaigns on the Ohio, a horrible waste and disorder prevailed at the Presqu'isle and Niagara carrying places, which cost the King immense sums. We have remedied all the abuses that have come to our knowledge, by submitting these portages to competition. The first is at forty sous the piece, and the other, which is six leagues in extent, at fifty. But we do not think the contractors can realize anything in consequence of the mortality among the horses and other expenses to which they are subject.

"Had we been favored with any tranquility, nothing would have been easier than to supply Fort Duquesne, by having the stores at Fort Presqu'isle filled during the summer, the horses could have rode the supplies during the winter to that of the River au Boeuf, whence they might be sent down the Ohio [Allegheny] on the first melting of the ice; but continual and urgent movements up to the present time have not afforded leisure to ride the effects in winter, and the horses are dying, which has determined us to give orders to draw from the Ohio as many of them as possible.

"Fort Duquesne could in less than two years support itself, since, in the very first year, 700 minots [a minot is a measure containing about three bushels] of Indian corn have been gathered there, and, from the clearings that have been made there since, it is calculated that if the harvest were good, at least 2,000 minots could be saved. Peas are now planted, and they have two cows, one bull, some horses and twenty-three sows with young." (25.)

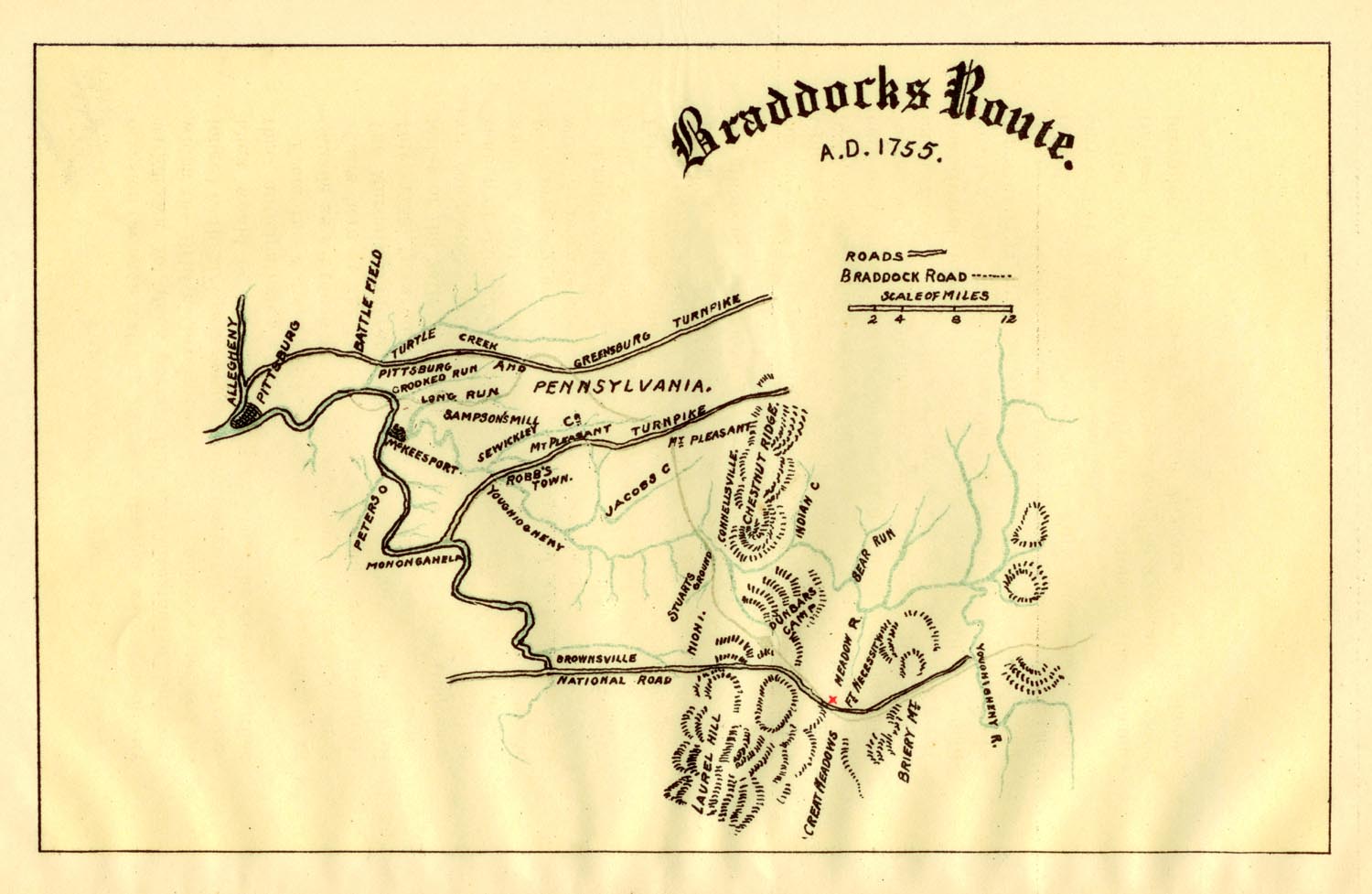

Map showing Braddock's Route, 1755.

On the 25th of November, 1754, Major-General Edward Braddock was commissioned General-in-Chief of His Majesty's forces in North America and received his instructions touching his duties with relation to the encroachments of the French. In this year also was held the Council at Albany. Early the next year, 1755, both governments sent reenforcements of men and large quantities of war munitions, to America; each force under convoy of a fleet.

Before the declaration of war, and before the breaking off of negotiations between the courts of France and England, the English ministry had formed a plan of assailing the French in America on all sides at once, and repelling them, by one bold push, from all their encroachments.

The original plan was not followed out in detail as contemplated but was somewhat altered as to the points of attack when operations were begun. A provincial army was to advance upon Acadia, a second was to attack Crown Point, and a third Niagara; while General Braddock, with two regiments which had lately arrived in Virginia, aided by a strong body of provincials, was to dislodge the French from Fort Duquesne.

Gen. Braddock sailed, Jan. 14, 1755, from Cork for America with the Forty-fourth and Forty-eighth Regiments of royal troops, each consisting of five hundred men, one of them commanded by Col. Dunbar and the other by Sir Peter Halket. He arrived at Alexandria, in Virginia, on the 20th of February. (26.)

In a council held at the camp there on the 14th of April, 1755, at which, besides himself and Hon. Augustus Keppel, Commander-in-Chief of his Majesty's ships and vessels in North America, there were present the Governors of Massachusetts, Virginia, New York, Maryland and Pennsylvania, three expeditions were then resolved on, the first of which was against Fort Duquesne, under the command of Gen. Braddock in person, with the British troops, with such aid as he could derive from Maryland and Virginia. There were afterwards added two independent companies from New York.

Gen. Braddock, at length, amply furnished with every thing necessary for the expedition, and confident of success, wrote to his friend Gov. Morris of Pennsylvania, from Fort Cumberland, on the 24th of May, that he should soon begin his march for Fort Duquesne, and that if he took the fort in the condition it then was, he should make what additions to it he deemed necessary, and leave the guns, ammunition and stores belonging to it with a garrison of Virginia and Maryland forces. But in case, as he apprehended, the French should abandon and destroy the fortifications, with the guns, stores and ammunitions of war, he would repair or construct some place of defence for the garrison which he should leave; but that Pennsylvania, Virginia and Maryland must immediately supply the artillery, ammunition, stores and provisions for the use and defence of the garrison left in the fort, as he should take all that he now had, and all that he should find in the fort along with him, for the further execution of his plan.

Having completed his arrangements, he sent forward on the 27th of May, Sir John Sinclair and Major Chapman, with a detachment of five hundred men to open the roads, and advance to the Little Meadows, erect a small fort, and collect provisions. On the 8th of June, the first brigade under Sir Peter Halket followed, and on the 9th the main body of the army, with the Commander-in-Chief, left Fort Cumberland, and commenced its march towards Fort Duquesne. He crossed the Allegheny Mountains at the head of two thousand two hundred men, well armed and supplied, with a fine train of artillery. In addition to these, Scarooyada, who had succeeded Half-King, a sachem of the Delawares, joined him with between forty and fifty friendly Indians; and the heroic Captain Jack, with George Croghan, the English Indian interpreter, who visited his camp, accompanied by a party, increasing the number of Indian warriors to one hundred and proposed to accompany the army as scouts and guides. These might have been of great use to him, in this capacity, might have saved the army from ambuscade and defeat. But he slighted and rejected them; and as the offer of their services was rather despised than appreciated, they left him in disgust; and retired to their fastnesses among the mountains of the Juniata.

In the seventh day after he left Fort Cumberland, he reached the Little Meadows, at the western base of the Allegheny Mountains, where the advance detachment under Sir John Sinclair, Quarter-Master General of the army, had before arrived. Here a council of war was called to determine upon a plan of future operations. Col. Washington who had entered the army as volunteer Aid-de-camp, and who possessed a knowledge of the country and the service to be performed, had at a previous council urged the substitution of pack-horses for wagons, in the transportation of the baggage. This advice was not taken at that time; but before the army reached the Little Meadows it was found that, besides the difficulty of getting the wagons along at all, they often formed a line of three or four miles in length; and the soldiers guarding them were so dispersed, that if an attack had been made either in front, center, or rear, the part attacked must have been cut off, or totally routed, before it could be sustained by any other part of the army. Washington again renewed his advice. He earnestly recommended that the heavy artillery and baggage should remain with a portion of the army, and follow by easy marches; while a chosen body of troops, with a few pieces of light cannon and such stores as were absolutely necessary, should press forward to Fort Duquesne. He enforced his counsel by referring to the information received of the march of five hundred men to reenforce the French whose delay was caused by the low state of the waters, which because would be removed by the rains, which in ordinary course, might be immediate.

This advice prevailed. Twelve hundred men with twelve pieces of cannon were selected from the different corps. They were to be commanded by Gen. Braddock, in person, assisted by Sir Peter Halket, acting as Brigadier General, Lieut. Col. Gage, Lieut. Col. Burton and Maj. Sparks. It was determined to take their thirty carriages including those that transporting the ammunition, and that the baggage and provisions should be carried upon horses. The General left the Little Meadows on the 19th of June, with his select body of troops, leaving Col. Dunbar and Maj. Chapman to follow by easy marching with the residue of the two regiments, some independent companies, the heavy baggage and the artillery.

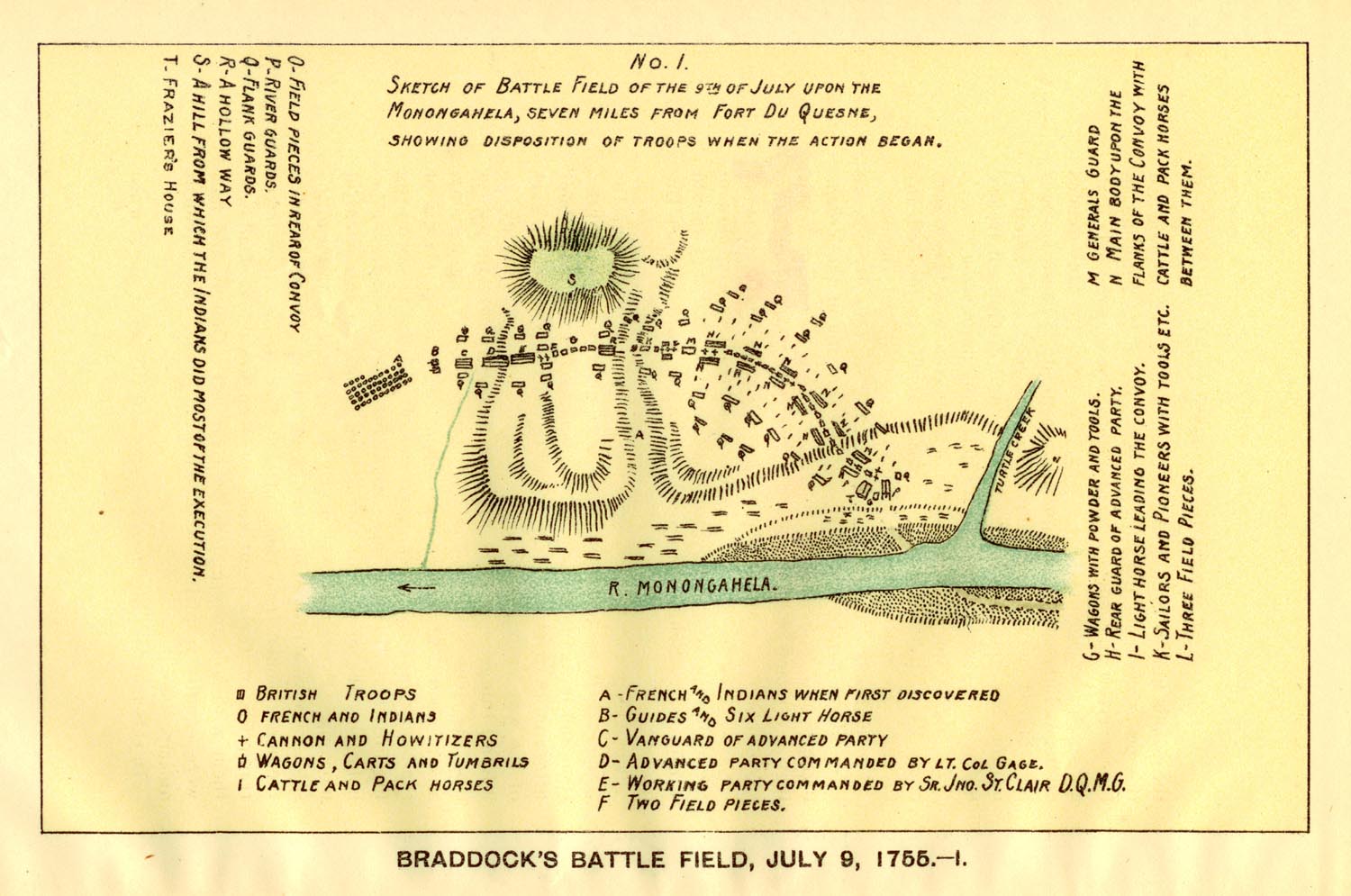

Map of Troop Formations, Braddock's Battle.

The benefit of these prudent measures was not lost on the fastidiousness and presumption of the Commander-in-Chief. "Instead of pushing on with vigor, regardless of a little rough road, he halted to level every mole hill, and to throw bridge over every rivulet," occupying four days in reaching the Great Crossings of the Youghiogheny, only nineteen miles from the Little Meadows. Mr. Peters, Secretary of the Colony of Penna., and one of the Commissioners to open the road from Fort Loudon to the forks of the Youghiogheny , strongly advised him that rangers should precede the army for its defence. But this advice was treated with contempt, and when on his march, Sir Peter Halket proposed that the Indians which were in the army should be employed in reconnoitering the woods and passages on the front and flanks, he rejected this prudent suggestion with a sneer. When Dr. Franklin, in his interview at Frederick, ventured to say, that the only danger he apprehended to his march, was from the ambuscades of the Indians–he contemptuously replied: "These savages may indeed be a formidable enemy to your raw American militia; but upon the King's regular and disciplined troops, Sir, it is impossible they should make any impression."

At the Little Meadows, Col. Washington was taken seriously ill with a fever, and rendered unable to proceed any further. He was thereupon left at the camp of Col. Dunbar.

On the 8th of July, the General arrived with his division, all in excellent health and spirits, at the junction of the Youghiogheny and Monongahela rivers. At this place Col. Washington rejoined the advanced division, being but partially recovered from the attack of fever, which had been the cause of his remaining behind. The officers and soldiers were now in the highest spirits, and firm in the conviction that they should within a few hours victoriously enter the walls of Fort Duquesne.

The steep and rugged grounds on the north side of the Monongahela prevented the army from marching in that direction, and it was necessary in approaching the fort, now about fifteen miles distant, to ford the river twice, and to march part of the way on the south side. Early on the morning of the 9th, all things were in readiness, and the whole train passed over the river a little below the mouth of the Youghiogheny, and proceeded in perfect order along the southern margin of the Monongahela. Washington was often heard to say during his life time, that the most beautiful sight he had ever beheld, was the display of the British troops on this eventful morning. Every man was neatly dressed in full uniform, the soldiers were arranged in columns and marched in exact order, the sun gleamed from their burnished arms, the river flowed tranquilly on their right and the deep forest overshadowed them with solemn grandeur on their left. Officers and men were equally inspirited with cheering hopes and confident anticipation.

In this manner they marched forward till about noon, when they arrived at the second crossing place, ten miles from Fort Duquesne. They halted but a little time, and then began to ford the river and regain its northern bank. As soon as they had crossed, they came upon a level plain, elevated but a few feet above the surface of the river, and extending northward nearly half a mile from its margin. Then commenced a gradual ascent at an angle of about three degrees, which terminated in hills of a considerable height at no great distance beyond. The road from the fording place to Fort Duquesne led across the plain and up this ascent, and thence proceeded through an uneven country, at that time covered with wood. (27.)

By the order of march, a body of three hundred men, under Col. Gage, made the advance party, which was immediately followed by another of two hundred. Next came the General with the columns of artillery, the main body of the army, and the baggage. At one o'clock the whole had crossed the river and almost at this moment a sharp firing was heard upon the advance parties, who were now ascending the hill, and had got forward about a hundred yards from the termination of the plain. A heavy discharge of musketry was poured in upon their front, which was the first intelligence they had of the proximity of an enemy; and this was suddenly followed by another on their right flank. They were filled with the greatest consternation, as no enemy was in sight, and the firing seemed to proceed from an invisible foe. They fired in return, however, but quite at random, and obviously without effect, as the enemy kept up a discharge in quick and continued succession.

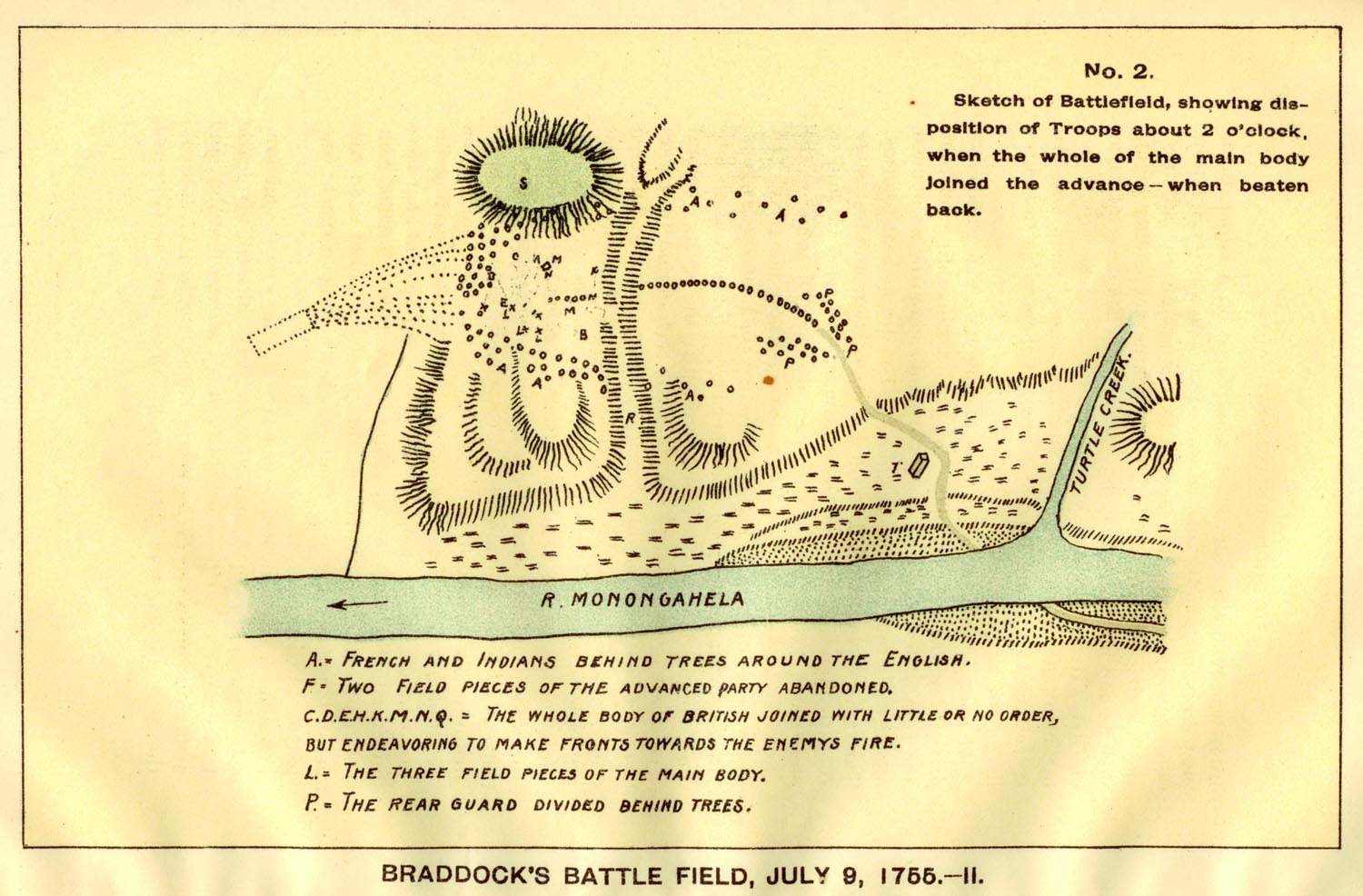

Map 2 of Troop Formations, Braddock's Battle.

The General advanced speedily to the relief of these detachments; but before he could reach the ground which they occupied, they gave way and fell back upon the artillery and the other columns of the army, causing extreme confusion, and striking the whole mass with such a panic that no order could afterwards be restored. The General and the officers behaved with the utmost courage, and used every effort to rally the men, and bring them to order; but all in vain. In this state they continued nearly three hours, huddling together in confused bodies, firing irregularly, shooting down their own officers and men, and doing no perceptible harm to the enemy. The Virginia Provincials were the only troops who seemed to retain their senses, and they behaved with a bravery and resolution never excelled. They adopted the Indian mode of warfare, and fought each man for himself behind a tree. This was prohibited by the General, who endeavored to form his men into platoons and columns, as if they had been manoeuvering on the plains of Flanders. Meantime the French and Indians, concealed in the ravines and behind trees, kept up a deadly and unceasing discharge of musketry, singling out their objects, taking deliberate aim, and producing a carnage almost unparalleled in the annals of modern warfare. More than half of the whole army which had crossed the river in so proud an array only three hours before were killed or wounded; the General himself had received a mortal wound, and many of his best officers had fallen by his side.

The rear was thrown into confusion, but the main body, forming three deep, instantly advanced. The commanding officer of the enemy having fallen, it was supposed from the suspension of the attack, that the assailants had dispersed. The delusion was momentary. The fire was renewed with great spirit and unerring aim, and the regular troops beholding their comrades drop round them, and, unable to see the foe, or tell from whence the fire came, which caused their death, broke and fled in utter dismay. Gen. Braddock, astounded at this sudden and unexpected attack, lost for the time his self-possession, and gave orders neither for a regular retreat, nor for his cannon to advance and scour the woods. He remained on the spot where he first halted, directing the troops to form into regular platoons, against a foe dispersed through the forest, behind trees and brushes, whose every shot did fatal execution upon his men. The colonial troops, whom he had contemptuously placed in the rear, instead of yielding to the panic which disordered the regulars, offered to advance against the enemy, until the British regiments could form, and bring up the artillery. But the regulars could not again be brought to the charge. They would obey no orders, but gathered themselves into a body, ten or twelve deep, and loaded, fired, and shot down the officers and men before them. Two-thirds of the killed and wounded in this fatal action received their shot from the cowardly and panic-stricken regulars. The officers were absolutely sacrificed by their good behavior; advancing in bodies, sometimes separately, hoping by such example, to engage the soldiers to follow them, but to no purpose.

The conduct of the Virginia troops was worthy of a better fate. They boldly formed and marched up the hill, but only to be fired at by the frightened royal troops. Captain Waggoner, of the Virginia forces, brought eighty men up to take possession of a hill, on the top of which a large fallen tree was lying of three or four feet in diameter, which he intended to use as a bulwark. He marched up and took possession, with shouldered arms, and with the loss of only three men killed by the enemy. As soon as his men discharged their pieces, upon the Indians in the ambuscade, which was exposed to him from their position, and when this movement might have driven the enemy from their coverts, the smoke of the discharge was seen by the British soldiery, and they fired upon the gallant little band, so that they were obliged to leave their position and retreat down the hill, with the loss of fifty killed out of eighty. The Provincial troops then insisted upon being allowed to adopt the Indian mode of warfare, and to shelter themselves behind trees; but General Braddock denied this request, and raged and stormed with great vehemence, calling them cowards and dastards. He even went so far as to strike them with his drawn sword for attempting to adopt this mode of warfare. He had four horses killed under him, and at last, on the fifth, received a mortal wound through the arm and lungs, and was carried from the field of battle.

A large portion of the regular troops had now fired away their ammunition, in an irregular manner, at their own friends, and had run off, leaving to the enemy the artillery, ammunition and stores. Some of them did not stop until they reached Dunbar's camp, thirty-six miles distant. Sixty-four out of eighty-five officers, and one-half of the privates were killed or wounded. Every field officer, and every one on horseback, except Col. Washington,–who had two horses killed under him, and four bullets through his coat,–was either slain or carried from the field disabled by wounds, and no hope remained of saving anything except by retreat. Washington then at the head of the Provincial troops, formed and covered the retreat with great coolness and courage.

The defeat was complete; the carnage great. Seven hundred and fourteen men were killed. The wagoners each took a horse from the teams and rode off in great haste; the example was followed by the soldiers; the rout became general; all order was disregarded, and it was with difficulty that Gen. Braddock and the wounded officers were brought off. All the artillery, ammunition, baggage and stores, together with the dead and dying, were left upon this fatal field, a prey to savage spoilers and the beasts of the forest. All the Secretary's papers, with all the Commanding General's orders, instructions, and correspondence, together with twenty-five thousand pounds in money, fell into the hands of the French.

The fugitives not being pursued, arrived at Dunbar's camp, and the panic they brought with them instantly seized him and all his troops. And although he had now about one thousand men, and the enemy which had surprised and defeated the detachment under Gen. Braddock, did not much exceed seven hundred Indians and French together, instead of proceeding and endeavoring to recover some of the lost honor, he ordered all the stores, ammunition, artillery and baggage, except what he reserved for immediate use, to be destroyed. Some of the heavy cannon he buried, and these have never been found. This he did in order that he might have more horses to assist his flight towards the settlements. More than half of the small arms were lost.

Arriving at Fort Cumberland, he was met with requests from the Governors of Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia, that he would post his troops on the frontier, so as to afford some protection to the inhabitants; but he continued his hasty march through the country, not thinking himself safe until he arrived at Philadelphia. In their first march, from their landing, till they got beyond the settlements, the British troops had plundered and stripped the inhabitants, totally ruining some poor families, besides insulting abusing, and confining the people, if they remonstrated.

Gen. Braddock having died in the night of the 13th of July, the day after Col. Dunbar had commenced his retreat, he was buried in the road, for the purpose of concealing his body from the Indians. He was wrapped in his cloak. The spot is still pointed out within a few yards of the National Road, and about a mile west of the site of Fort Necessity at the Great Meadows. The French sent out a party as far as Dunbar's camp, and destroyed everything that was left. Col. Washington being in very feeble health, retired to Mount Vernon.

The loss of the French was slight, but fell chiefly on the officers, three of whom were killed, and four wounded. Of the regular soldiers, all but four escaped untouched. The Canadians suffered still less, in proportion to their numbers, only five of them being hurt. The Indians, who won the victory, bore the principal loss. Of those from Canada, twenty-seven were killed and wounded, while casualties among the western tribes are not reported. All of these last went off the next morning with their plunder and scalps, leaving Contrecoeur in great anxiety lest the remnant of Braddock's troops, reenforced by the division under Dunbar, should attack him again. His doubts would have vanished had he known the condition of his defeated enemy.

Pitiable, indeed, was the condition of the defeated General and of those who remained near him. In the pain and languor of a mortal wound, Braddock showed unflinching resolution. His bearers stopped with him at a favorable spot near the Monongahela; and here he hoped to maintain his position till the arrival of Dunbar. By the efforts of the officers about a hundred men were collected around him; but to keep them was impossible. Within half an hour they abandoned him, and fled like the rest. Gage, however, succeeded in rallying about eighty beyond the other fording place; and Washington, on an order from Braddock, spurred his jaded horse towards the camp of Dunbar to demand wagons, provisions, and hospital stores.

Fright overcame fatigue. The fugitives toiled on all night, pursued by spectres of horror and despair; hearing still the war-whoops and the shrieks; possessed with the one thought of escape from this wilderness of death. In the morning some order was restored. Braddock was placed on a horse; then the pain being insufferable, he was carried on a litter, Captain Orme having bribed the carriers by the promise of a guinea and a bottle of rum apiece. Early in the succeeding night, such as had not fainted on the way reached the deserted farm of Gist. Here they met wagons and provisions, with a detachment of soldiers sent by Dunbar, whose camp was six miles farther on; and Braddock ordered them to go to the relief of the stragglers left behind.

At noon of that day a number of wagoners and packhorse-drivers had come to Dunbar's camp with wild tidings of rout and ruin. More fugitives followed; and soon after a wounded officer was brought in upon a sheet. The drums beat to arms. ! The camp was in commotion; and many soldiers and teamsters took to flight, in spite of the sentinels, who tried in vain to stop them. There was a still more disgraceful scene on the next day, after Braddock, with the wreck of his force, had arrived. Orders were given to destroy such of the wagons, stores and ammunition as could not be carried back at once to Fort Cumberland. Whether Dunbar or the dying General gave these orders is not clear; but it is certain that they were executed with shameful alacrity. More than a hundred wagons were burned; cannon, coehorns and shells were burst or buried; barrels of gunpowder were staved, and the contents thrown into a brook, provisions were scattered through the woods and swamps. Then the whole command began its retreat over the mountains to Fort Cumberland, sixty miles distant. This proceeding, for which, in view of the condition of Braddock, Dunbar must be held answerable, excited the utmost indignation among the colonists. If he could not have advanced, they thought, he might at least have fortified himself and held his ground till the provinces could send him help; thus covering the frontier, and holding French war parties in check.

Braddock's last moment was near. Orme, who though himself severely wounded, and who was with him till his death, told Franklin that he was totally silent all the first day, and at night said only: "Who would have thought it?"–that all the next day he was silent again, till at last he muttered, "We shall better know how to deal with them another time," and died a few minutes after. He had nevertheless found breath to give orders at Gist's for the succor of the men who had dropped on the road. It is said, too, that in his last hours "he could not bear the sight of a red coat," but murmured praises of "the blues," or Virginians, and said that he hoped he should live to reward them. He died at about eight o'clock in the evening of Sunday, the thirteenth of July. Dunbar had begun his retreat that morning, and was then encamped near the Great Meadows. On Monday the dead Commander was buried in the road; and men, horses', and wagons, as we have seen, passed over his grave, effacing every sign of it, lest the Indians should find and mutilate the body.

We have in the Narrative of Captain James Smith an account of what occurred in the fort on the morning of the 9th of July, when the French sallied forth to battle, and what he witnessed when he returned. His account is as follows :

"Some time after I was there [Fort Duquesne], I was visited by the Delaware Indian already mentioned, who was at the taking of me, and could speak some English. I asked what news from Braddock's army? He said, the Indians spied them every day, and he showed me by making marks on the ground with a stick, that Braddock's army was advancing in very close order, and that the Indians would surround them, take trees, and (as he expressed it,) shot um down all one pigeon.

"Shortly after this, on the 9th day of July, 1755, in the morning, I heard a great stir in the fort. As I could then walk with a staff in my hand, I went out of the door, which was just by the wall of the fort, and stood upon the wall and viewed the Indians in a huddle before the gate; where were barrels of powder, bullets, flints, &c., and every one taking what suited; I saw the Indians also march off in rank entire– likewise the French Canadians, and some regulars. After viewing the Indians and French in different positions, I computed them to be about four hundred, and wondered that they attempted to go out against Braddock with so small a party. I was then in high hopes that I would soon see them fly before the British troops, and that General Braddock would take the fort and rescue me.

"I remained anxious to know the event of this day; and, in the afternoon, I again observed a great noise and commotion in the fort, and though at that time I could not understand French, yet found that it was the voice of joy and triumph, and feared that they had received what I called bad news.

"I had observed some of the old country soldiers speak Dutch; as I spoke Dutch, I went to one of them and asked him, what was the news? He told me that a runner had just arrived, who said that Braddock would certainly be defeated; that the Indians and French had surrounded him, and were concealed behind trees and in gullies, and kept a constant fire upon the English, and that they saw the English falling in heaps, and if they did not take the river, which was the only gap, and make their escape, there would not be one man left alive before sun-down. Some time after this I heard a number of scalp haloos, and saw a number of Indians and French coming in. I observed they had a great many bloody scalps, grenadiers' caps, British canteens, bayonets, &c., with them. They brought the news that Braddock was defeated. After that, another company came in, which appeared to be about one hundred, and chiefly Indians, and it seemed to me that almost everyone of this company was carrying scalps; after this came another company with a number of wagon horses, and also a great many scalps. Those that were coming in, and those that had arrived, kept a constant firing of small arms, and also the great guns in the fort, which were accompanied with the most hideous shouts and yells from all quarters; so that it appeared to me as if the infernal regions had broken loose.

"About sundown I beheld a small party coming in with about a dozen prisoners, stripped naked, with their hands tied behind their backs, with their faces and part of their bodies blackened. These prisoners they burned to death on the bank of Allegheny river opposite to the fort. I stood on the fort wall until I beheld them begin to burn one of these men; they had him tied to a stake, and kept touching him with fire brands, red-hot irons, &c., and he screamed in a most doleful manner,– the Indians in the meantime yelling like infernal spirits. As this scene appeared too shocking for me to behold, I retired to my lodgings both sore and sorry. In the morning after the battle, I saw Braddock's artillery brought into the fort; the same day I also saw several Indians in British officers' dress, with a sash, half moons, laced hats, &c., which the British then wore.

"A few days after this the Indians demanded me, and I was obliged to go with them."

As pertinent to this narration, the papers following are taken from the French reports of this campaign and they are inserted here for the purpose of showing it from their point of view.

From a "Journal of the Operations of the Army from 22d of July to 30th of September, 1755:"

"July 16th.– The enemy had three armies, one destined for the Beautiful river, where they were defeated. The corps was three thousand strong, under the command of General Brandolk [Braddock), whose intention was to besiege Fort Duquesne; they had considerable artillery, much more than was necessary to besiege forts in this country, most of which are good for nothing, though they have cost the King considerable. M. de Beaujeu, who was in command of that fort, notified of their march, and much embarrassed to prevent the siege with his handful of men, determined to go and meet the enemy. He proposed it to the Indians who were with him, who at first rejected his advice and said to him: No, Father, you want to die and sacrifice yourself; the English are more than four thousand, and we are only eight hundred, and you want to go and attack them. You see clearly that you have no sense. We ask until to-morrow to make up our minds. They consulted together; they never march without doing so. Next morning M. de Beaujeu left his fort with the few troops he had, and asked the Indians the result of their deliberations. They answered him: They could not march. M. de Beaujeu, who was kind and affable, and possessed sense, said to them: I am determined to go and meet the enemy. What! will you allow us to go alone? I am sure of conquering them. The Indians, thereupon, decided to follow him. This detachment was composed of 72 Regulars, 146 Canadians and 637 Indians. The engagement took place within four leagues of the fort on the 9th day of July, at 1 o'clock in the afternoon, and continued until five. M. de Beaujeu was killed at the first fire. The Indians, who greatly loved him, avenged his death with all the bravery imaginable. They forced the enemy to fly with a considerable loss, which is not at all extraordinary. The Indian mode of fighting is entirely different from that of us Europeans, which is good for nothing in this country. The enemy formed themselves into battle array, presented a front to men concealed behind trees, who at each shot brought down lone or two, and thus defeated almost the whole of the English, who were for the most part veteran troops that had come over the last winter. The loss of the enemy is computed at 1,500 men. M. de Brandolk, their General, and a number of officers have been killed. 13 pieces of artillery, a great quantity of balls and shells, cartridge boxes, powder and flour have been taken; 100 beeves, 400 horses, killed or captured, all their wagons taken or broken. Had not our Indians amused themselves plundering, not a man would have escaped. It is very probable that the English will not make any further attempt in that direction, inasmuch as, in retiring, they have burnt a fort they had erected for their retreat. We have lost three officers, whereof M. de Beaujeu is one, 25 soldiers, Canadians or Indians; about as many wounded."

An account of the battle of the Monongahela, 9th of July, 1755:

"M. de Contrecoeur, Captain of Infantry, Commandant of Fort Duquesne, on the Ohio, having been informed that the English were taking up arms in Virginia for the purpose of coming to attack him, was advised, shortly afterwards, that they were on the march. He despatched scouts, who reported to him faithfully their progress. On the 17th instant he was advised that their army, consisting of 3,000 regulars from Old England, were within six leagues of this fort. That officer employed the next day in making his arrangements; and on the 9th detached M. de Beaujeu, seconded by Messrs. Dumas and de Lignery, all three Captains, together with four Lieutenants, 6 Ensigns, 20 Cadets, 100 Soldiers, 100 Canadians and 600 Indians, with orders to lie in ambush at a favorable spot, which he had reconnoitred the previous evening. The detachment, before it could reach its place of destination, found itself in presence of the enemy within three leagues of that fort. M. de Beaujeu, finding his ambush had failed, decided on an attack. This he made with so much vigor as to astonish the enemy, who were waiting for us in the best possible order; but their artillery, loaded with grape (a cartouche), having opened its fire, our men gave way in turn. The Indians, also, frightened by the report of the cannon rather than by any damage it could inflict, began to yield, when M.. de Beaujeu was killed. M. Dumas began to encourage his detachment. He ordered the officer in command of the Indians to spread themselves along the wings so as to take the enemy in flank, whilst he, M. de Lignery and the other officers who led the French, were attacking them in front. This order was executed so promptly that the enemy, who were already shouting their "Long live the King" thought now only of defending themselves. The fight was obstinate on both sides and the success long doubtful; but the enemy at last gave way. Efforts were made, in vain, to introduce some sort of order in their retreat. The whoop of the Indians, which echoed through the forest, struck terror into the hearts of the entire enemy. The rout was complete. We remained in possession of the field with six brass twelves and sixes, four howitz-carriages of fifty, eleven small royal grenade mortars, all their ammunition, and, generally, their entire baggage. Some deserters, who have come in since, have told us that we had been engaged with only 2,000 men, the remainder of the army being four leagues further off. These same deserters have informed us that the enemy were retreating to Virginia, and some scouts, sent as far as the height of land, have confirmed this by reporting that the thousand men who were not engaged, had been equally panic-striken and abandoned both provisions and ammunition on the way. On this intelligence, a detachment was despatched after them, which destroyed and burnt everything that could be found. The enemy have left more than one thousand men on the field of battle. They have lost a great portion of the artillery and ammunition, provisions, as also their General, whose name was Mr. Braddock, and almost all their officers. We have had three officers killed; two officers and two cadets wounded. Such a victory so entirely unexpected, seeing the inequality of the forces, is the first of M. Dumas experience, and of the activity and valor of the officers under his command."

After making allowance for the exaggeration which is manifest in the French official reports, the battle, the victory, and the results were wonderful things for them. No one can help but feel a sort of admiration at the intrepid bravery of those officers who led their forces against such odds, and the devotion of those followers who went out as to a certain death. Of this motley force Mr. Parkman says:

"The garrison consisted of a few companies of the regular troops stationed permanently in the colony, and to these were added a considerable number of Canadians. Contrecoeur still held the command. Under him were three other captains, Beaujeu, Dumas, and Ligneris. Besides the troops and Canadians, eight hundred Indian warriors, mustered from far and near, had built their wigwams and camp-sheds on the open ground, or under the edge of the neighboring woods,—very little to the advantage of the young corn. Some were baptised savages settled in Canada,—Caughnawages from Saut St. Louis, Abenakis from St. Francis, and Hurons from Lorette, whose chief bore the name of Anastase, in honor of that Father of the Church. The rest were unmitigated heathens,—Pottawattamies and Ojibwas from the northern lakes under Charles Langlade, the same bold partisan who had led them, three years before, to attack the Miamis at Pickawillany; Shawanoes and Mingoes from the Ohio; and Ottawas from Detroit, commanded, it is said, by that most redoubtable of savages, Pontiac. The law of the survival of the fittest had wrought on this heterogenous crew through countless generations; and with the primitive Indian, the fittest was the hardiest, fiercest, most adroit, and most wily. Baptised and heathen alike, they had just enjoyed a diversion greatly to their taste."

That Fort Duquesne was built by Contrecoeur as the Commander of the expedition and the chief officer in this region and that it was under his command for a time, has never been called in question. But since the discovery of the Register (28) and other documents of a later period, a dispute has arisen as to who the actual commander of the fort was at the time of the battle of Braddock's Field.

On this subject the Rev. Father Lambing, in his translation of the Register says:

"It was formerly generally asserted that he [Contrecoeur] was in command at the time of the battle of the Monongahela, more commonly known as Braddock's Defeat; and that he was succeeded early in the spring of 1756 by M. John Daniel, Esquire, Sieur Dumas, Captain of Infantry. It was further stated that he was by no means disposed to favor Beaujeu's proposed attack upon Braddock's army. But the discovery of the Register, now published, would appear to prove this long entertained opinion erroneous; for in the entry of the latter's death, he is said to be "commander of Fort Duquesne and of the army." But on the other hand, there is not wanting evidence which would go to show that Contrecoeur in command. He was commander of the fort from the date of its construction, but in the winter of 1754-5, he asked to be relieved, and the Marquis Duquesne, the Governor-General, dispatched Captain Beaujeu to relieve him, ordering him at the same time to remain at the fort until after the engagement with the English."

Mr. Francis Parkman, after giving the matter special attention in view of the statements made on the basis of the baptismal register and elsewhere, has added a lengthy note as an appendix to the latest edition of his Montcalm and Wolfe, in which he says:

"It has been said that Beaujeu, and not Contrecoeur, commanded at Fort Duquesne at the time of Braddock's Expedition. Some contemporaries, and notably the chaplain of the fort, do, in fact, speak of him as in this position; but their evidence is overborne by more numerous and conclusive authorities, among them Vaudreuil, Governor of Canada, and Contrecoeur himself, in an official report."

In the reports referred to by Mr. Parkman, the Governor of Canada states that Contrecoeur was the Commandant at the Fort on the 8th of July, and that he sent out a party which was commanded by Beaujeu, to meet the English. In the autumn of 1756, the Governor in asking the Colonial Minister to procure pensions for Contrecoeur and Ligneris, stated that the former gentleman had commanded for a long time at Fort Duquesne–from the first establishment of the English and their retirement from Fort Necessity to the defeat of the army under Gen. Braddock.

For his conduct on the 9th of July, Dumas was early promoted to succeed Contrecoeur in the command of Fort Duquesne. Here he proved himself as active and vigilant officer, his parties ravaging Penna., and penetrating far into the interior. A letter of instructions signed by him, on 23d of March, 1756, was found in the pocket of the Sieur Donville, who, being sent to surprise the English at Fort Cumberland, got the worst of it and lost his own scalp. This letter concludes in a spirit of humanity honorable to its writer.

M. de Ligneris relieved Dumas of the command some time late in 1756, as he is named as the commander on the 27th of December of that year. De. Ligneris retained command until the French were expelled from the soil of Penna. He was one of the last to leave with his men from the burning Fort Duquesne, whence he retired to Fort Machault, (Venango) where we hear of him later.

We have the following description of the fort from one John McKinney, who, having been taken prisoner by the Indians was carried first to Fort Duquesne and thence to Canada, from whence he made his escape and came to Philadelphia, where he made this statement in February, 1756:

"Fort Duquesne is situated on the east side of the Monongahela, in the fork between that and the Ohio. It is four square, has bastions at each corner; it is about fifty yards wide–has a well in the middle of the Fort, but the water bad–about half the Fort is made of square logs, and the other half next the water of stockadoes; there are intrenchments cast up all round the Fort about 7 feet high, which consists of stockadoes drove into the ground near to each other, and wattles with poles like basket work, against which earth is thrown up, in a gradual ascent; the steep part is next the Fort, and has three steps all along the intrenchment for the men to go up and down, to fire at the enemy—These intrenchments are about four rods from the Fort, and go all around, as well on the side next the water as the land; the outside of the intrenchment next the water joins to the water. The Fort has two gates, one of which opens to the land side, and the other to the water side, where the magazine is built; that to the land side is, in fact, a draw-bridge, which in day-time serves as a bridge for the people, and in the night is drawn up by iron chains and levers.

"Under the drawbridge is a pit or well, the width of the gate, dug down deep to water; the pit is about eight or ten feet broad; the gate is made of square logs; the back gate is made of logs also, and goes upon hinges, and has a wicket in it for the people to pass through in common; there is no ditch or pit at this gate. It is through this gate they go to the magazine and bake-house, which are built a little below the gate within the intrenchments; the magazine is made almost under ground, and of large logs and covered four feet thick with clay over it. It is about 10 feet wide, and about thirty-five feet long; the bake-house is opposite the magazine; the waters sometimes rise so high as that the whole Fort is surrounded with it, so that canoes may go around it; he imagines he saw it rise at one time near thirty feet. The stockadoes are round logs better than a foot over, and about eleven or twelve feet high; the joints are secured by split logs; in the stockadoes are loop holes made so as to fire slanting to the ground. The bastions are filled with earth solid about eight feet high; each bastion has four carriage guns about four pound; no swivels, nor any mortars that he knows of; they have no cannon but at the bastion. The back of the barracks and buildings in the Fort are of logs placed about three feet distant from the logs of the Fort; between the buildings and the logs of the Fort, it is filled with earth about eight; feet high, and the logs of the Fort extend about four feet higher, so that the whole height of the Fort is about 12 feet.

"There are no pickets or palisadoes on the top of the Fort to defend it against scaling; the eaves of the houses in the Fort are about even with the top of the logs or wall of the Fort; the houses are all covered with boards, as well the roof as the side that looks inside the Fort, which they saw there by hand; there are no bogs nor morasses near the Fort, but good dry ground; a little without musket shot of the Fort, in the fork, is a thick wood of some bigness, full of large timber.

"About thirty yards from the Fort, without the intrenchments and picketing, is a house, which contains a great quantity of tools, such as broad and narrow axes, planes, chisels, hoes, mattocks, pick-axes, spades, shovels, &c., and a great quantity of wagon-wheels and tire. Opposite the Fort, on the west side of the Monongahela, is a long, high mountain, about a quarter of a mile from the Fort, from which the Fort might very easily be bombarded, and the bombarder be quite safe; from them the distance would not exceed a quarter of a mile; the mountain is said to extend six miles up the Monongahela, from the Fort, Monongahela, opposite the Fort, is not quite a musket shot wide, neither the Ohio nor the Monongahela can be forded, opposite the Fort. The Fort has no defence against bombs. There are about 250 Frenchmen in this Fort; besides Indians, which at one time amounted to 500; but the Indians were very uncertain; sometimes hardly any there; that there were about 20 or 30 ordinary Indian cabins about the Fort.

"While he was at Fort Duquesne, there came up the Ohio from the Mississippi, about thirty batteaux, and about 150 men, loadened with pork, flour, brandy, tobacco, peas, and Indian corn, they were three months in coming to Fort Duquesne, and came all the way up the falls without unloading."

The description of Fort Duquesne by Parkman, contrasting the period of the French occupancy with our own time, may aptly be reproduced (29.)

"Fort Duquesne stood on the point of land where the Allegheny and Monongahela join to form the Ohio, and where now stands Pittsburgh, with its swarming population, its restless industries, the clang of its forges, and its chimneys vomiting foul smoke into the face of heaven At that early day a white flag fluttering over a cluster of palisades and embankments betokened the first intrusion of civilized man upon a scene which, a few months before, breathed the repose of a virgin wilderness, voiceless but for the lapping of waves upon the pebbles, or the note of some lonely bird. But now the sleep of ages was broken, the bugle and drum told the astonished forest that its doom was pronounced and its days numbered. The fort was a compact little work, solidly built and strong, compared with others on the continent. It was a square of four bastions, with the water close on two sides, and the other two protected by ravelins, ditch, glacis, and covered way. The ramparts on these sides were of squared logs, filled in with earth, and ten feet or more thick. The two water sides were enclosed by a massive stockade of upright logs, twelve feet high, mortised together and loopholed. The armament consisted of a number of small cannon mounted on the bastions. A gate and draw-bridge on the east side gave access to the area within, which was surrounded by barracks for the soldiers, officers quarters, the lodgings of the commandant, a guard-house, and a store-house, all built partly of logs and partly of boards. There were no casements, and the place was commanded by a high woody hill beyond the Monongahela. The forest had been cleared away to the distance of more than a musket shot from the ramparts, and the stumps were hacked level with the ground. Here, just outside the ditch, bark cabins had been built for such of the troops and Canadians as could not find room within; and the rest of the open space was covered with Indian corn and other crops."

It is now known that the French had little hope of preserving this fort from its threatened attack. Vaudreuil writes to Machault from Montreal, 24th of July, 1755—before he had news of the defeat of Braddock:

"Fort Duquesne is really threatened. On the 7th of this month the English were within 6 or 8 leagues of it; I am informed by letter that they number 8,000, being provided with artillery and other munitions for a siege.

"I would not be uneasy about this fort, if the officer in command there had all these forces; they consist of about 1,600 men, including regulars, militia and Indians,—with which he would be in a condition to form parties sufficient and considerable to annoy the march of the English from the first moment he had any knowledge thereof; these parties would have harrassed and assuredly repulsed them. Everything was in our favor in this regard, and affording us a very considerable advantage.

"But, unfortunately, no foresight had been employed to supply that fort with provisions and munitions of war, so that the Commandant, being in want of the one and the other, is obliged to employ the major portion of his men in making journeys to and fro for the purpose of transporting those provisions and munitions, which cannot even reach him in abundance, in consequence of the delay at the Presq'isle portage and the lowness of the water in the River Au Boeuf.

"I must also observe that Fort Duquesne has never been completed; on the contrary, ‘tis open to many capital defects, as is proved by the annexed plan.

"'Tis true that the Commandant, urged by the officers of the garrison, who perceived all the defects, took upon himself early in the spring, to demand sub-engineer de Lignery of the Commandant at Detroit, which officer had put the fort in the best condition he was able, without, however, daring to make any alterations in it.

"I dread with reason, my Lord, the first intelligence from that fort, I shall be agreeably surprised if the English have been forced to abandon their expedition." (30.)

The defeat of Braddock left the frontiers of Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia in unutterable gloom. With one accord the Indian tribes rose against the English. From now on until late in 1758, when the French departed, there was one continuous series of surprises, attacks, of killings, and of captivity. There was one episode, however, which for a time brought relief to the northwestern frontier of Pennsylvania; and was partially effective in staying the maurauding of the savages. This was the attack on the Indian town of Kittanning, on the Allegheny, by Colonel John Armstrong in September of 1756. The substantial advantage which he gained by this adventure was timely and of the greatest consequence to those settlements which were nearest to this harborage; but its advantages were not so noticeable on the more southern frontiers which were open to the savages who harbored about Fort Duquesne.

Governor Morris, in his message to the Assembly, July 24th, 1755, in anticipation of this condition of affairs, says: "This unfortunate and unexpected change in our affairs [he alludes to Braddock's Defeat] deeply affects every one of his Majesty's colonies, but none of them in so sensible a manner as this province; while having no militia it is hereby left exposed to the cruel incursions of the French and barbarous Indians, who delight in shedding human blood, and who made no distinction as to age or sex; to those that are armed against them, or such as they can surprise in their peaceful habitations, all are alike the objects of their cruelty—slaughtering the tender infant and frightened mother, with equal joy and fierceness. To such enemies, spurred by the native cruelty of their tempers, encouraged by their late success, and having now no army to fear, are the inhabitants of this province exposed; and by such may we now expect to be overrun, if we do not immediately prepare for our own defense." (31.)

Later in the fall in a letter to Governor Dinwiddie, Governor Morris says that the mischiefs done by these merciless Indians in this province since my last letter are inconceivable. All our settlements contiguous to Maryland, westward of the ending of the temporary line, are broken up, and many of their houses burned. The same ravages have been committed in the Big and Little Cove; and then these savages finding the people there armed and on the march against them, quitted their depredations on the west side of Susquehanna, crossed that river and fell on the rich vale of Tulpyhoccon, murdering and burning plantations, as low as within six miles of Mr. Weiser's house. (32.)

The following is from the Abstract of Dispatches received from Canada, officially, from Vaudreuil, Governor-General of the Colony, and they set forth the methods of the French during the winter and early spring of 1756. (33.)

"The Governor remained at Montreal, in order to be in a more convenient position to harass the English during the winter, and to make preparations for the next campaign. With this double object he directed his efforts principally to gaining the Indians, and flatters himself that he has generally succeeded.

"All the Nations of the Beautiful River have taken up the hatchet against the English. The first party that was formed in that quarter, since the last report Vaudreuil had sent in the month of October (1755), was composed of two hundred and fifty Indians, to whom the Commandant at Fort Duquesne had joined some Frenchmen at the request of those Indians.

"This party divided themselves into small squads, at the height of land, and fell on the settlements beyond Fort Cumberland; defeated a detachment of twenty regulars under the command of two officers. After these different squads had destroyed or carried away several families, pillaged and burnt several houses, they came again together with the design of surprising Fort Cumberland, and accordingly lay in ambush during some time; but the Commandant of the fort, who no doubt was on his guard, dared not show himself. This party returned to Fort Duquesne with sixty prisoners and a great number of scalps.

"The second detachment, which consisted of a military Cadet, a Canadian and Chaouanons, (Shawanese) took two prisoners under the guns of Fort Cumberland, whither the party had been sent by the Commandant of Fort Duquesne, to find out what was going on there.

"The third, made up of a Canadian and several Chaouanons, destroyed eleven families, burned sixteen houses and one mill, and killed a prodigious number of cattle. The Indians returned on horseback.

"The fourth party was composed of one hundred and twelve Delawares (Loups). They struck in separate divisions. Thirteen returned, first, with twenty-one scalps and six prisoners. The remainder of the party took such a considerable number of scalps and prisoners that these Indians sent some to all the nations to replace their dead.

"Vaudreuil reported only what these four parties did. A number of others had marched with equal success. Some bad actually been on the war path as far even as Virginia.

"The Commandant of Fort Duquesne had informed Vaudreuil that the Delawares settled beyond the mountains which separated them from the English, had, on his invitation, just removed their villages so as to unite with their brethren, our allies; that the old men, the women and children, had already gone with the baggage; and that the warriors were to form the rear guard and, on quitting, to attack the English."

The following extracts, taken from the same sources, give the French version of the affairs as they transpired on our frontiers and about Fort Duquesne while it continued in their occupancy:

"The latest news from Fort Duquesne is to the 9th of May, 1756. (34.) No English movements of any importance yet in that quarter. Our Indians, together with some of our detachments, made many successful forays. Thirty scalps have been sent us, and the commissions of 3 officers of the English regiment raised in the country, who have been killed. The Upper country Indians carried off entire families, which obliges the English to construct several pretended forts; that is to say, to enclose a number of dwellings with stockades. Our Upper Indians appear well disposed towards us, notwithstanding the presents and solicitations of the English. M. Dumas, an officer of great distinction in the Colony, commands at Fort Duquesne and on the River Ohio. We have lost, in one detachment, Ensign Douville, of the Colonial troops. * * *